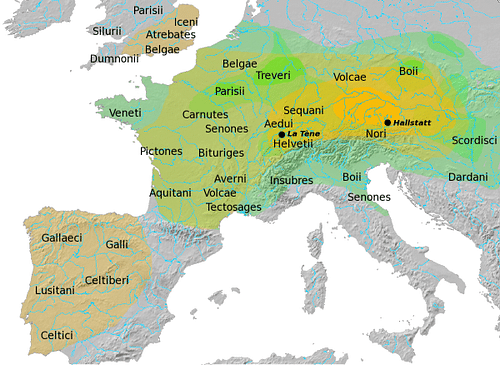

The La Tène Culture (c. 450 - c. 50 BCE) is named after the site of that name on the northern shores of Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland. It replaced the earlier Hallstatt culture (c. 1200 - c. 450 BCE) as the dominant culture of central Europe, especially in terms of art. Artefacts of the La Tène culture have been discovered in a wide arc covering western and central Europe, spanning from Ireland to Romania.

The La Tène culture is often incorrectly equated with the mid-Iron Age Celts, despite its documented presence in areas both inside and outside territories occupied by speakers of the Celtic language. The La Tène culture went into decline following the conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar (c. 100-44 BCE) in the mid-1st century BCE, even if elements continued to be seen in the material culture of Celtic peoples in Britain and Ireland.

The Hallstatt Culture

The Hallstatt culture, which derives its name from the site on the west bank of Lake Hallstatt in Upper Austria, was dominant in central Europe from c. 1200 to c. 450 BCE (the Late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age). Sometimes called a proto-Celtic culture, these peoples thrived thanks to the exploitation and trade of such local resources as salt and iron. Their prosperity is evidenced in large mound tombs containing a rich array of goods, which include imported luxury items from the Mediterranean cultures to the south, especially the Greek colonies in southern France and the Etruscans in north-central Italy. From around 600 BCE the Hallstatt peoples seem to have become more preoccupied with warfare as sites became fortified. There were also fewer but more powerful settlements over the next two centuries, suggesting an increase in competition for resources and, likely, too, for trade opportunities. There was also an increase in trade activity from the side of the Mediterranean states eager to find new markets for their mass-produced goods like wine. Production of salt at the Hallstatt mines ended by c. 400 BCE and so we might suppose that this diminishing wealth resulted in the Mediterranean states looking elsewhere for trading partners.

It is now that the La Tène culture, named after the site of that name in western Switzerland, comes to the fore, perhaps contemporary with the Hallstatt settlements for a generation (c. 460 - c. 440 BCE) and then completely replacing them as many of the latter were abandoned. In some rare cases, Hallstatt settlements continued to be occupied in the La Tène period, a notable example being Hohenasperg in southern Germany. The La Tène sites initially occupied territory in what is today France, southern Germany, Switzerland and Bohemia, mostly around key river points such as the Loire, Marne, Moselle, and Elbe.

La Tène: Definition & Problems of Use

The name 'La Tène' was, and sometimes still is, applied by some archaeologists and historians to what we today might more commonly call 'the Celts', especially in reference to material culture and, in particular, art. Both terms are problematic as they cover a multitude of peoples across time and space in Europe. It can be said that there were cultural and religious changes in the peoples of central Europe during the Iron Age and so the terms Hallstatt culture, La Tène culture and Celtic culture remain useful to distinguish more or less distinct phases of cultural development in this region from the 13th century BCE up to the expansion of the Roman Empire from the 1st century BCE onwards and into the medieval period. However, these terms disguise the complex relations between different western and central European tribes, the overlapping of some cultural features in time and space and the isolation and uniqueness of other such features. The European Iron Age was certainly a vibrant period of cultural interaction, trade relations, warfare and migrations, and the dynamism of the period does not lend itself well to such umbrella terms as 'La Tène' or 'the Celts'. Accordingly, such terms, although sometimes useful, should be used with caution.

A further problem with the term 'La Tène' is that it has become widely used as a synonym for Celtic culture even though it is documented as being present in only some areas occupied by Celtic-speaking peoples and in other areas not at all connected with the Celts such as non-Celtic parts of Iberia and Germanic-speaking Denmark. Further, it has been proven that there were speakers of the Celtic language before the arrival of the La Tène culture. As the historian J. Collis notes: "The common equation of a 'La Tène Culture' with the Celts is one that is no longer acceptable either on methodological or factual grounds." (in Bagnall, 3851). In addition, the very word 'culture' is misleading since "it is better to envisage this period as one of small interacting societies which share many common traits" (ibid).

Material Culture

The people of the La Tène culture dedicated offerings of precious goods to their gods, and this was frequently done, as in later Celtic cultures such as in Britain, by throwing them in water, in this case, Lake Neuchâtel. There is evidence of a wooden bridge which once crossed a narrow part of the lake. This bridge was either the platform from which offerings were deposited into the lake or these items were attached to the bridge which subsequently collapsed in the waters below when the culture declined. The first artefacts were found in the lake in the 1850s CE when its waters were artificially lowered. Finds include weapons and armour such as iron swords, sword scabbards, spears, and shields, as well as smaller items like brooches, animal figurines (especially dogs, pigs, and cattle), and even human bones.

One of the features which unite La Tène sites is a distinctive art style, which shows influence from Greek and Etruscan art. The style was prevalent across the whole European continent from Ireland to Romania.

Features of La Tène art include:

- stylised masks and human figures

- curved geometric shapes (S-forms, spirals, and symmetrical forms)

- vegetal designs (especially palmettes and lotus flowers)

- a love of fantastic creatures like winged horses and griffins.

Excavations of La Tène elite burials have revealed a great many artefacts such as gold torcs, weapons, imported goods from the Mediterranean and two-wheeled chariots. The latter vehicles are a point of contrast with the four-wheeled waggons in Hallstatt tombs, as is the abundance of weapons in La Tène burials. A particularly rich site in artefacts is Glauberg in Hesse, Germany. An impressive life-sized sandstone statue, sometimes called the 'Prince of Glauberg', was excavated at the site. This warrior, who carries a shield, is wearing a mail tunic and a torc necklace with three pendants. He also wears an elaborate headdress known as the 'leaf crown' type. The statue was found near an already excavated tomb, which dates to the second half of the 5th century BCE, and the jewellery worn by the statue is similar to that worn by the deceased warrior in the tomb. The statue is on display in the Glauberg Museum.

Migration

La Tène hilltop sites began to be abandoned during the 4th century BCE, and burials which include precious and imported goods become rarer (except on the periphery of the culture’s presence such as in northern France). This is likely connected with the 'Celtic migration' of the 4th-3rd century BCE when peoples in central Europe moved southwards, attacking the Romans, amongst others, and settling in such places as the northern shores of the Black Sea and in eastern Asia Minor (where they became known as Galatians). They also moved from central Europe westwards to the Atlantic coast and into Britain.

Meanwhile, back in western-central Europe towards the end of the 3rd century BCE, the La Tène culture flourished as trade was re-established with the southern parts of the continent. Slaves, furs, gold, and amber (acquired from Baltic peoples), in particular, were traded with southern cultures. Sites like Manching on the River Danube in southern Germany and Aulnat in the Auvergne region of central France became major trading hubs. This trade is evidenced throughout the 2nd century BCE by the introduction of coinage and the massive number of finds of Roman wine amphorae.

Decline

Then things started to turn sour. The first symptom of strained relations, most likely caused by increased competition for resources and trade opportunities, was the building of oppida in the 2nd and 1st century BCE. An oppidum was the Roman name for larger settlements, which we now apply specifically to fortified sites, usually located on high points in the landscape or on plains at naturally defensible points like river bends. The fortifications usually consisted of an earthworks circuit wall, sometimes with outer ditches. Oppida were not necessarily places of permanent occupation, although some were used as such. Rather, many were, in times of war, used as a point of refuge and otherwise as a safe place to concentrate manufacturing workshops and store the community’s resources. This hostile environment deteriorated further when the Romans became intent on conquest, beginning in 125 BCE with attacks on the Arverni tribe in Gaul. Julius Caesar then attacked and conquered Gaul in the middle of the next century, and the empire went on expanding from there, assimilating continental European peoples into Roman culture. Features of La Tène culture did, though, continue into the medieval period in more isolated places like Ireland and northern Britain.