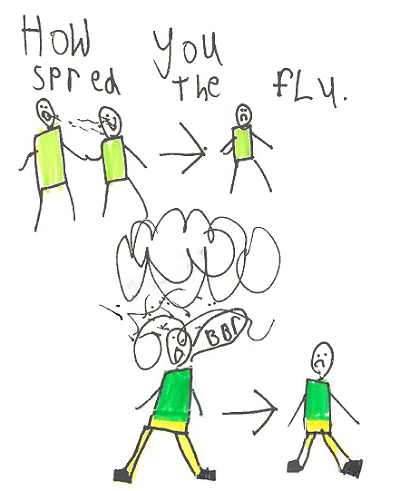

The flu happens every year, worldwide. All of us might be potentially affected by the flu. Therefore, we asked children from the different countries to draw the symptoms of the flu and the preventive measures which they know. This Spotlight is illustrated with the drawings of children aged 5-15 years from Australia, Democratic Republic of Congo, Denmark, Latvia, Switzerland and Tajikistan.

Influenza: are we ready?

When 100 passengers on a flight from Dubai to New York in September 2018 fell ill with respiratory symptoms, health officials were concerned that they might be carrying a serious respiratory illness called MERS-CoV (Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus) and quarantined the plane until further health checks could be completed. Testing showed that several were positive for the influenza virus, which can be easily spread when people are in close contact or in contained spaces such as airports and planes for several hours.

Influenza may not always be thought of by most people as a serious illness – the symptoms of headaches, runny nose, cough and muscle pain can make people confuse it with a heavy cold. Yet seasonal influenza kills up to 650 000 people every year. That is why influenza vaccinations are so important, especially to protect young children, older people, pregnant women, or people who have vulnerable immune systems (click here for a Facebook live with Dr Martin Friede on the flu vaccine).

What most of us think of as ‘the flu’ is seasonal influenza, so called because it comes around in the coldest season twice a year (once in the Northern hemisphere’s winter, and once in the Southern hemisphere’s winter) in temperate zones of the world, and circulates year-round in the tropics and subtropics.

The influenza virus is constantly mutating – essentially putting on ever-changing disguises – to evade our immune systems. When a new virus emerges that can easily infect people and be spread between people, and to which most people have no immunity, it can turn into a pandemic. "Another pandemic caused by a new influenza virus is a certainty. But we do not know when it will happen, what virus strain it will be and how severe the disease will be,” said Dr Wenqing Zhang, the manager of WHO’s Global Influenza Programme. “This uncertainty makes influenza very different to many other pathogens,” she said.

2018 marks the 100th anniversary of one of the most catastrophic public health crises in modern history, the 1918 influenza pandemic known colloquially as “Spanish flu”. This Spotlight focuses on the lessons we can learn from previous flu pandemics, how prepared we are for another one, and how work on seasonal flu can boost capacity for pandemic preparedness.

Cover your mouth and nose when coughing or sneezing

Wash your hands regularly

Drink plenty of water and rest

If you have a vulnerable immune system, you may need antivirals

Don't take antibiotics - they don't work against cold or flu viruses

Get the flu vaccine every year - even if you do get the flu, your symptoms will be milder

Avoid being around people who are sick

Try not to touch your eyes, nose or mouth - germs are most likely to enter your body this way

Clean and disinfect surfaces if you are sharing a home with someone who is sick

Wash your hands regularly

The 1918 flu pandemic

The intensity and speed with which the 1918 influenza pandemic struck were almost unimaginable – infecting one-third (around 500 million people) of the Earth’s population. By the time the pandemic subsided two years later, more than 50 million people are estimated to have died. Globally, the death toll eclipsed that of the First World War, which was around 17 million.

There was actually nothing “Spanish” about the 1918 pandemic. While it had already taken a big toll in France and the USA, it was not made public in those countries because of wartime censorship. French doctors even referred to it by the code name “maladie onze”, meaning "disease 11”. When the disease surfaced in Spain, which was neutral during the war, the country had no censorship in place and so made the first public reports of the pandemic. The name stuck.

A unique disease

Pathogens ignore national borders, social class, economic status, and even age. While influenza is typically more deadly in very young or elderly people, the 1918 influenza pandemic, for instance, was unusually fatal among men aged 20 to 40 years.

Pandemics disrupt the economy and social functions like school, work and other mass gatherings. An influenza pandemic would also likely have significant impacts on the overall functioning of a country's health system, as it would draw heavily on resources and health workers.

A flu pandemic is predicted to cost US$60 billion every year, but pandemic preparedness in contrast, could cost only US$4.5 billion a year.

Just as with many other diseases, influenza pandemics impact poor and socially marginalized communities the hardest. A study in The Lancet looking at the potential impact of a 1918-like pandemic on the modern world found that "the countries and regions that can least afford to prepare for a pandemic will be affected the most."

The world looks very different from it did 100 years ago, however. Unlike the world affected by the 1918 influenza pandemic, we now have antivirals, vaccines, diagnostic tests, and modern surveillance techniques. Many of these advances were spearheaded by WHO in close collaboration with other agencies and national and regional institutions. We also have learned from subsequent pandemics in the 20th and 21st century.

As this Spotlight will show, we have more tools to combat pandemics than ever before. These include the development of a global influenza surveillance system that constantly monitors the evolution of circulating influenza strains, the development of an unprecedented agreement to ensure sharing of flu viruses and data alongside strengthening global preparedness capacities, efforts to continuously improve the effectiveness of the seasonal influenza vaccine, and powerful new antivirals. However, for the next influenza pandemic, there are still challenges ahead and in particular ensuring optimum global collaboration between all countries in the world and defining mechanisms that allow equitable access to vaccines, treatments and diagnostics for everyone, everywhere.

"We have the ability, now more than ever, to mitigate the impact of diseases, save lives and reduce economic and social costs. But countries' preparedness efforts should be maintained and should integrate innovative lifesaving interventions," said Dr Sylvie Briand, director of WHO’s department of Infectious Hazard Management.

Predictably unpredictable

Map: Deaths from the 2009 influenza pandemic

The 2009 “Swine flu” A(H1N1) pandemic started in Mexico where it caused severe illness in previously healthy adults and spread rapidly to over 214 countries and overseas territories or communities. Between 105 000 and 395 000 people are thought to have died. Even so, the world was relatively lucky: it turned out to be milder than some seasonal epidemics, which can kill twice that number.

An international committee convened by WHO reviewed the response to the 2009 pandemic and found that “The world is ill-prepared to respond to a severe influenza pandemic or to any similarly global, sustained and threatening public-health emergency.” The committee called for not only the strengthening of core public-health capacities, but also increased research, a multisectoral approach, strengthened health-care delivery systems, economic development in low and middle-income countries and improved health status.

Preparing the world for the next pandemic

In 1947, a year before WHO`s constitution came into force, the WHO Interim Committee of the United Nations established a Global Influenza Programme to track changes in the virus. The sharing of viruses and data between different nations in order to have up-to-date vaccines thus became one of the core tools in the fight against both seasonal and pandemic influenza.

In 1952, WHO launched the Global Influenza Surveillance Network with 26 collaborating laboratories around the world. Today, renamed the Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS), the 66-year old network comprises 153 institutions in 114 countries. It constantly monitors influenza viruses causing seasonal outbreaks in people, zoonotic outbreaks, and potential pandemics and makes vaccine selection decisions twice a year, for the northern and southern hemisphere influenza seasons. Countries with National Influenza Centres share virus samples and data to support this continuous monitoring.

"GISRS is the frontline in the fight against influenza. It is one of the oldest and most significant examples of international cooperation for public health,” said Dr Zhang. "Confidence, trust and sharing, with commitment from Member States, is critical to pandemic preparedness."

"Pandemic influenza is a significant public health issue that we are unable to prevent or eliminate, given our current technology and knowledge. So much of our work managing the pandemic has to be when it occurs, to impact on health and society," said Dr Zhang. "Seasonal influenza epidemics provide real opportunities to prepare for the next pandemic. To achieve the best possible outcome now and in the future, there are three critical factors: timeliness and quality of virus and information sharing, research and innovation, and global coordination. For pandemic influenza, the world has to work as one team," she said.

Every week, countries report newly detected influenza cases to WHO through a system called FluNet. Another system, FluID, looks at the epidemiology of the circulating viruses associated with influenza. WHO is also developing a pandemic influenza severity assessment tool (PISA) to provide baselines so that there is a barometer by which to compare the virulence of the virus as new strains emerge.

“What's unique about influenza is it is constantly changing. So for seasonal viruses, these viruses continue to evolve and change and escape the ability of existing vaccines to protect the population,” said Dr Jacqueline Katz, Director of the WHO Collaborating Centre for the Surveillance, Epidemiology and Control of Influenza, Atlanta, USA. “We're really concerned about being ahead of the game for detecting a virus that could cause the next global pandemic."

Pandemic preparedness

The re-emergence in 2004 of a highly virulent influenza virus with pandemic potential triggered global discussions about access to pandemic vaccines by developing countries. Some countries, affected by high numbers of human infections, voiced concern that they were sharing virus samples with GISRS, while knowing that if a pandemic were to occur, they might not have access to the vaccines made using information and materials from those samples. To strengthen the sharing of influenza viruses with human pandemic potential and to increase the access of developing countries to vaccines and other critical pandemic response supplies, the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework was set up in 2011 by the 194 Member States of WHO. This framework would help countries in need to access vaccines, antivirals, and diagnostics at the time of a pandemic.

Two of the main benefits of the agreement are: first, vaccine manufacturers that receive vaccine viruses from GISRS must commit to provide to WHO about 10% of their future pandemic vaccine production, so that it can be distributed to countries in need at the time of the next pandemic. Second, influenza product manufacturers that use GISRS are expected to contribute US$28 million a year to WHO that then uses the funds to bolster the ability of countries to respond to pandemics.

"By working with industry partners, we can strengthen global preparedness capacities in countries where they are weak. In return, countries are enabling the GISRS network to perform a thorough risk assessment by sharing influenza viruses with pandemic potential," said Anne Huvos, manager of the PIP Framework secretariat at WHO.

Are we ready for the next pandemic?

Influenza is an ever-evolving disease, so the work on prevention, preparedness and response has to adapt continuously to keep up with these changes.

WHO and partners are developing a renewed Global Influenza Strategy to be launched this year. This will support countries in developing seasonal influenza prevention and control capacities. These national efforts, in turn, will build greater global preparedness for the next pandemic. The strategy focuses on three priorities, strengthening pandemic preparedness, expanding seasonal influenza prevention and control and research and innovation. Research and innovation includes improved modelling and forecasting of influenza outbreaks, along with the development of new vaccines, including a possible universal influenza vaccine that would work against all influenza virus strains.

However, developing and distributing a vaccine during a pandemic could take up to a year. This means that non-pharmaceutical measures - the same as those needed to stop seasonal flu - will be critical. Some of these are actions that individuals can take, including staying home when sick and washing hands frequently.

Organizations could also take measures such as implementing policies to limit gatherings where the virus may be easily spread; WHO is currently developing guidance on such measures. These new guidelines will draw on evidence as well as experience from the 1918 and 2009 pandemics. However, even with the best infection prevention and control measures, some people will still fall ill with influenza – for people with severe influenza, there are effective antivirals to cure it.

Today, less than half of all countries have a national influenza pandemic preparedness plan; of those, few have updated their plans to take into account the lessons learned from 2009. Not surprisingly, low-income countries, which are struggling to bolster their own primary health care systems, often lack the resources or bandwidth to develop and implement pandemic preparedness plans.

At the core of effective pandemic response is a strong, well-resourced health system that includes adequately trained and paid health workers; functioning water, sanitation, and hygiene systems; quality laboratory services for rapid diagnosis; access to medical products including vaccines; and reliable systems for tracking and reporting cases of the disease.

"We still have challenges with improving international coordination and mobilizing sufficient and sustainable resources for preparedness and research to make better vaccines, antivirals and diagnostics," said Dr Briand. "Most importantly, these counter-measures need to be available to all countries, particularly those communities with the least resources as they will be the most vulnerable in the next flu pandemic."

Some of this content first appeared in Pandemic influenza: an evolving challenge.

Join WHO in taking action

While you are here, take a minute to sign up to our weekly updates and free online courses on flu. We'll be in touch with health advice and latest findings to improve your health and wellbeing.

Subscribe to our weekly updates

Online courses on flu

Become a WHO volunteer