Lynching is the illegal killing of a person under the pretext of service to justice, race, or tradition. Though it often refers to hanging, the word became a generic term for any form of execution without due process of law. Though it is hard to estimate the frequency of lynchings before the 1880s, it seems that they occurred only sporadically before 1865, and were likely to be the result of "frontier justice" dispensed in areas where formal legal systems did not exist.

In antebellum Texas and earlier, vigilantes instigated most lynchings. Often acting under the leadership of the local elite, the vigilante mob usually handled its victims with considerable formality, imitating legal court procedure. The captured offender was "tried" before a vigilante judge and a jury consisting of either a select group of vigilantes or the whole of the assembled mob. Convictions most often resulted in whipping, followed by expulsion from the community, but at least seventeen vigilante organizations resorted to the noose, claiming some 140 lives. The earliest of these groups, the Shelby County Regulators of 1840–44, killed at least ten people during the Regulator-Moderator War. The San Saba County lynchers, the deadliest of the lot, claimed some twenty-five victims between 1880 and 1896. Vigilante lynching died out in the 1890s, but other varieties of mobs continued.

It is uncertain when the first of the non-vigilante lynch mobs appeared in Texas, but certainly they increased in frequency with the approach of the Civil War. In the five years preceding the war, mobs frequently sought out suspected slave rebels and White abolitionists. The most serious outbreak of this sort occurred in North Texas in 1860, when rumors of a slave insurrection led to the lynching of an estimated thirty to fifty slaves and possibly more than twenty Whites (see TEXAS TROUBLES, SLAVE INSURRECTIONS). The stresses of the Civil War, such as racism, regional loyalties, political factionalism, economic tension, and the growth of the abolition movement, inured people to violence in a way that seemed to make lynching increasingly easy to contemplate. War-generated tensions produced the greatest mass lynching in the history of the state, the Great Hanging at Gainesville, when vigilantes hanged forty-one suspected Unionists during a thirteen-day period in October 1862.

The use of organized terror by lynch mobs appeared in Texas during Reconstruction as the Ku Klux Klan and similar organizations resorted to violent methods of restoring White supremacy. The humiliation of defeat, increasing idleness and violence, mistrust of all levels of government, alteration of the traditional racial order, and fear of violence by African Americans all contributed to a great outbreak of lynch-mob activity and instilled in many Whites a belief in a "right to lynch." The Klan declined in Texas in the early 1870s and experienced a brief resurgence in the 1920s. Immediately after Reconstruction, lynch law evidently declined somewhat, but it soon increased again, and began to be characterized by events in which mobs removed victims from legal custody, sometimes with the cooperation of legal authorities. In 1885 an estimated twenty-two mobs lynched forty-three people, including nineteen African Americans and twenty-four Whites, one of whom was female. After this the number of lynching victims generally decreased, dropping to five in 1893, but increased again to twenty-six in 1897. The number of victims continued to decline (to twenty-three in 1908 and fifteen in 1909) until 1915, when there were thirty-two. The 1915 figure, which is probably an underestimate, reflected an increase in racial hostility that accompanied the spread of Jim Crow laws and border troubles growing out of the Mexican Revolution. Six mobs in Cameron, Willacy, and Hidalgo counties accounted for twenty-six of the victims. The Jesse Washington lynching, in which a Black teenager was mutilated and burned by a Waco mob in 1916, drew national condemnation but much less denouncement within the state .

In 1922 thirteen mobs claimed fifteen victims. The lynchings in Kirvin in Freestone County were particularly heinous. In May 1922 the rape and murder of Eula Ausley, a White girl in Kirvin, resulted in the forcible seizure of three suspects—McKinley “Snap” Curry, Moses Jones, and John Cornish—from the Freestone County jail by a White mob that then mutilated and burned the three near the Kirvin business district. A fourth man, Shadrack Green, who was implicated in the crime, was later found shot and hanging from a tree. In each case, at least circumstantial evidence pointed to other suspects .

After 1922 there was a sharp decline in lynchings; 1925 was the first lynching-free year. The Sherman Riot in 1930, however, was a notable example of racial violence committed by a mob. After 1930 there was never more than one mob a year. Six years without a lynching preceded the final clear-cut case, the lynching of accused rapist William Vinson at Texarkana on July 13, 1942.

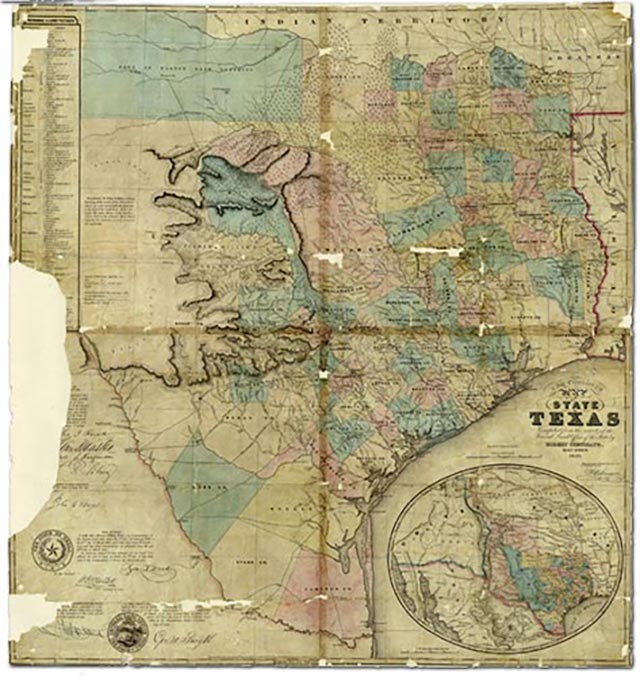

Texas stands third among the states, after Mississippi and Georgia, in the total number of lynching victims. Of the 468 victims in Texas between 1885 and 1942, 339 were Black, 77 White, 53 Hispanic, and 1 American Indian. Half of the White victims died between 1885 and 1889, and 53 percent of the Hispanics died in the 1915 troubles. Between 1889 and 1942 charges of murder or attempted murder precipitated at least 40 percent of the mobs; rape or attempted rape accounted for 26 percent. African Americans were more likely to be lynched for rape than were members of other groups, although even among African Americans murder-related charges accounted for 40 percent of the lynchings and alleged rape for only 32 percent. All but 15 of the 322 lynching incidents that have a known locality occurred in the eastern half of the state. The heaviest concentration of mob activity was along the Brazos River from Waco to the Gulf of Mexico, where eleven counties accounted for 20 percent of all lynch mobs. Other concentrations were in Harrison and neighboring counties on the Louisiana border, adjacent to Caddo Parish, Louisiana, one of the most lynching-prone areas in the country, and in Lamar and surrounding counties in Northeast Texas.

Texans also made important contributions to the antilynching movement. Part of this was unintentional: the gruesome and widely publicized 1893 torture-burning of Henry Smith before an assembly of thousands at Paris helped galvanize the infant antilynching movement into action. In a more positive vein, Texas native Jessie Daniel Ames of Georgetown founded and served as president of the Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, the most effective antilynching group in the country. The legislature passed an antilynching law in 1897, governors called out the Texas Volunteer Guard to help defend prisoners on numerous occasions, and local officers sometimes went to great lengths to protect their prisoners.