Timelessness is a difficult thing. There are certain forms of storytelling, like myths and legends or fables and fairy tales, that have endured up through the present day. Sometimes these read like works that could have endured for centuries: though some of his other works have embraced metafiction and experimental forms, Neil Gaiman’s Norse Mythology is a more straightforward retelling of centuries-old narratives. Others take a different approach: the tales in Joanna Walsh’s Grow a Pair echo the archetypal characters and surreal transformations of fairy tale classics, but add a more contemporary view of gender and sexuality.

The best reworkings of older stories or older methods of storytelling help reinvigorate the archaic, or give readers a new way of seeing the contemporary world. Go the wrong way, though, and you can end up with something that seems tonally dissonant, an attempt to bridge eras that collapses under the weight of a certain literary conceit.

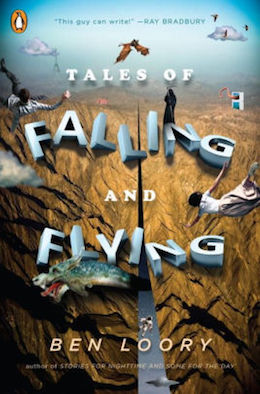

Ben Loory’s fiction represents another approach to reviving older forms, one which blends bold characters with a host of authorial quirks. The front cover of Loory’s new collection, Tales of Falling and Flying, boasts a blurb from none other than Ray Bradbury–which is probably the first indication that Loory’s fiction falls into something of a classical mode. Along with that is the collection’s title, which echoes his earlier book, Stories for Nighttime and Some for the Day, and the Author’s Note that opens the book, which consists of three sentences that apologize for taking “so long,” and promising that his next collection will be out sooner.

From the outset, there’s a playfulness here—but there’s also a sense of Loory’s voice as a storyteller. One can imagine him at a podium in carnival-barker mode, about to tell a hushed audience about the stranger sides of life exposed in these brief narratives. While that’s an image worthy of Loory’s Technicolor parables, it may not be entirely accurate; in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, he noted that “[e]verybody knows perfectly well what makes a good story when people are telling stories, like if you’re at a party or a dinner.”

The stories in Loory’s new collection swerve at the reader in unexpected ways. The narrator of “The Cracks in the Sidewalk” lives in a town in which the names of all of the residents are spelled out in an unexpected place, creating a surreal perspective on questions of belonging and community. In “James K. Polk,” the former president is reimagined as a man torn between his obsession with growing the smallest tree imaginable and the duties of a head of state. And the title character of “The Sloth” moves to the city in the hopes of finding a job, but ultimately discovers a slightly different calling.

And then there’s “The Squid Who Fell in Love with the Sun.” It opens in the manner of a fable, delineating the ways in which its title character had been fixated on the sun from an early age. He tries a series of maneuvers in order to reach his beloved: jumping high, designing a pair of wings, and then creating a craft that can travel through space. From there, though the story takes an unexpected shift: at the conclusion of his journey, the squid suddenly realizes the folly of his decision, and that his trip will soon lead to his death. “He wrote out all his knowledge, his equations and theorems, clarified the workings of everything he’d done,” Loory writes. The squid beams this information out into the cosmos—where, eventually, an alien civilization discovers it and is forever transformed.

It’s an oddly unexpected note of transcendence, and one which suddenly shifts the scale of this already-eccentric narrative into an entirely different strata. If it resembles anything, this particular story in particular evokes the lyrics of Loudon Wainwright III’s “The Man Who Couldn’t Cry,” which begins like a tall tale and simultaneously becomes more cosmopolitan and more surreal as its narrative develops.

Some of these stories turn on reversals of fortune; others use time-honored narrative tricks to reach unlikely epiphanies. But for all of the weirdness present here—strange histories, altered spaces, talking animals—there’s also a sense of sincerity. Loory isn’t winking when he presents questions of love or loneliness; he’s aiming at a very particular sense of timelessness and agelessness.

In a recent interview about the collection, Loory said that “I’m much more focused on what the stories feel like to read, on the shape of their experience, than I am on their explication.” That, too, may contribute to their particular mode: these don’t really feel archaic, even as certain qualities of the storytelling might not have been out of place in a lost classic unearthed after being initially published decades ago. These are stories that seem familiar yet, at their best, feel fresh—it’s a winning sense of deja vu.

Tales of Falling and Flying is available from Penguin Books.

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).

Tobias Carroll is the managing editor of Vol.1 Brooklyn. He is the author of the short story collection Transitory (Civil Coping Mechanisms) and the novel Reel (Rare Bird Books).