I think it might help this discussion to offer some sense of how I came to my views on culture and white supremacy. I want to go back to the original piece I wrote, "A Culture of Poverty," and highlight an exchange I had in comments. Then I want to point to a recent note I received which helped clarify things even more.

Many of you know Yoni Appelbaum. He came to us originally under the handle Cynic. I can name several academics who've influenced my thinking over the past five years—Barbara Fields, Nell Irvin Painter, Drew Gilpin Faust, Patrick Sharkey, Arnold Hirsch, Khalil Gibran Muhammad, Tony Judt, and a bunch more. As much as any of the people, Yoni has helped me really sharpen my thinking on the centrality of white supremacy in American history. (This is not gush. There's an entire section of this piece that I owe to him.)

In the original column I had a hazy notion about practices fitting environments. Put differently, I believed that culture made sense when understood within the context in which it operated. One might note, for instance, that married black women—as a practice—tend to have fewer children then married white women. I actually don't know why that is. But if I wanted to find out, I would start from the premise that there is something tangible, discernible, and knowable in the world of married black people that animates that practice. Too often "culture" is basically spoken in the way one might say "magic."

I later sharpened that point in other columns. But it was Yoni who first bought this home for me:

Spot on.

But I'd add that it works this way in reverse, too. It's a point seldom made. I was reading a new memoir the other day, by a Harvard graduate who went to work as a prison librarian. Much of the book is an account of his acculturation. He discovered that his robes and spell books, so to speak, were a lot less useful than plate and a broad-sword. That he couldn't afford to be seen as a punk. He was perfectly equipped for a comfortable, upper-middle-class life—and wholly unprepared for his new environment.

We tend to associate culturally-specific practices with the relative successes of the cultures with which they're associated. Things rich people do must be beneficial; habits of the poor, not. The reality is more complex. Culture of Poverty is a label attached to a wide array of behaviors. There are behaviors—physical assertiveness—well-suited to that environment that may tend to inhibit success elsewhere. There are other behaviors—emphasis on familial and communal ties—that will cut both ways, sustaining people in difficult times but sometimes making it harder for them to place their individual needs above the demands of the group. And there are others—initiative and self-reliance—that are largely positive, and in many ways, even more advantageous if carried further up the social scale.

I bristle when I see people discuss the culture of poverty as a pathology. That's too self-congratulatory, and too cramped a view. The reality is that, like all cultures, it has aspects that translate well to other circumstances, those that translate poorly, and those that are just plain different. And that's no different than the Culture of Affluence.

That was crucial. I understood that cultural practices made sense in their context. But Yoni complicated it even further—some practices hurt, some practices help, and some practices don't matter at all. This really was a knock-you-on-your-ass moment for me, because I could think of my own life and see exactly that. At Howard University, I had a culture—a set of practices—that I employed in intellectual debate that are different than most people I encounter online. We tended to argue from history, and there was premium (somewhat obnoxious) on book citations.

That tradition came out of a sense that we had been "robbed" of history and culture and had to reclaim it—as Douglass did, as Malcolm did, as Zora did. Consider the constant (if inaccurate) quip employed in the black community that the easiest place to hide something from a nigger (and that was how it was said) was between the pages of a book. We were responding to that. My style of arguing—a practice coming out of my environment—was formed there. I would not trade it for anything.

I talk to Yoni from time to time. In fact, a lot of us here at The Atlantic do. (Rebecca Rosen calls him the best critical reader of The Atlantic, hands down.) Taking in the early portion of the culture-of-poverty debate, Yoni offered the following:

Your post sends me back to The North American Review, which asked, in 1912, "Are the Jews an Inferior Race?" It answered the question, resoundingly, in the negative, but the more salient point is that the point was then very much in doubt. After the long centuries Jews spent in Europe marked as a minority, tolerated or persecuted, there was no shortage of thinkers willing to advance the claim that Jewish inferiority was innate, or at the very least, an ineradicable element of a broken culture. "Based on anthropology and biased by personal psychology," explained the author, "anti-Semitic literature advances the theory that the Jewish race is divested of the higher forms of genius and is to be regarded as an uncreative, imitative, practical, and utilitarian body. Mental inferiority and spiritual impotency circulate accordingly in the very blood of the Jew."

The article was, itself, a response to a letter in a previous issue that considered that the Jews, in "all their immiscibility," had survived centuries without sovereignty only at the cost of producing, "a character so unattractive, even repellent, their shortcomings even in righteousness and their insignificance in everything else, without poetry, without science, without art, and without character."

That's one example. There are innumerable others. My point is that, at the time, it seemed perfectly reasonable to conclude that Jewish culture, whether innate or the product of prolonged persecution, had itself become a significant impediment to success. But that, a century later, it seems impossible to reconcile the idea that Jewish culture was the problem with the record of success that Jews produced over the following hundred years, in those nations in which they were not similarly persecuted.

Now, we get Jed Rubenfeld explaining how that same culture—formerly blamed for Jewish inferiority—is actually a distinct advantage. And just so, a hundred years from now, there will be bestsellers explaining how black culture, forged in centuries of adversity, accounts for the remarkable success of the African-American community. The point is that the same sets of cultural characteristics operate very differently in different circumstances. And to focus on the culture—rather than the circumstances—seems obtuse.

Yoni is the Yoni of Atlantic Media.

More seriously, I really would like to see more historians in these debates. We have plenty of people with economics background, with political-science backgrounds, and some even with sociology backgrounds. But it feels like there is a massive gulf between how people who study American history see their country, and how not just Americans but American journalists see their country. Forgive me if that is too sweeping.

I keep thinking about this idea of pessimism. A few weeks ago I was at Rhodes College for a conference. I ended up sitting at dinner with the historian Thavolia Glymph, and some other historians of note. Glymph's work is a corrective to the idea that there was some sort of sisterhood between plantation matriarchs and enslaved black women. She was talking about some of the evidence she'd seen and she said that—"When you read a woman's diary and in the middle of dinner she pulls out a knife and slashes her servant, you start to understand." That's not an exact quote. But the point I am making is that I've had the luxury of reading, and now visiting with, a number of scholars (historians, anthropologists, some multi-disciplinary folks) and what you get isn't The Adventures of Flagee and Ribbon.

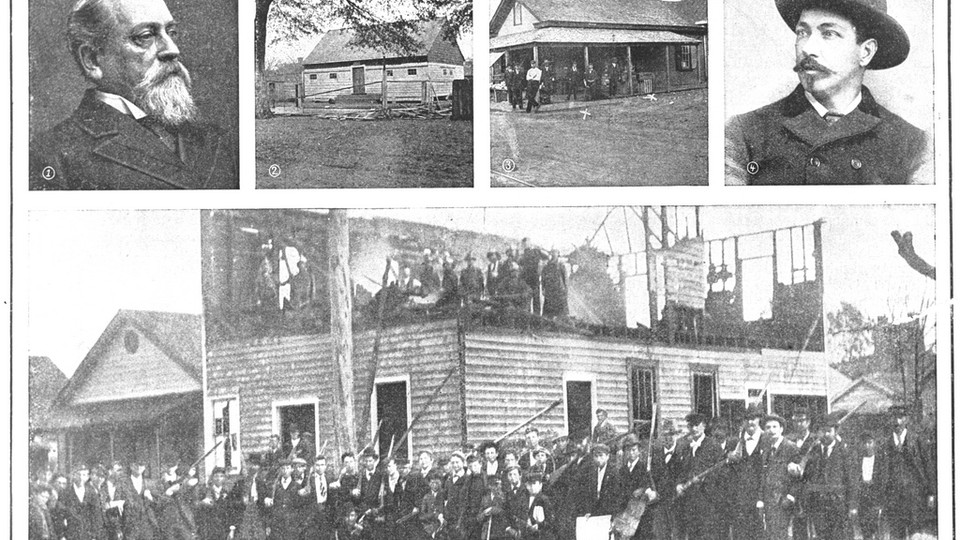

Indeed you often get something much darker then what I'm giving you here. At that same conference I was noting—as I often do—that the Wilmington coup in 1898 is the only coup in American history. The historians in the room looked at me like I was crazy. (Timothy Tyson literally shouted "Noooooo" from the audience.) That's because, as I was told, the truth is much worse. There have been plenty of coups in American history—most of them dating to Reconstruction, and animated by white supremacy. How's that for depressing?

We deserve more of that in our lives. We deserve to see ourselves fully. It's not our history that makes me fatalistic, it's our history of looking away.