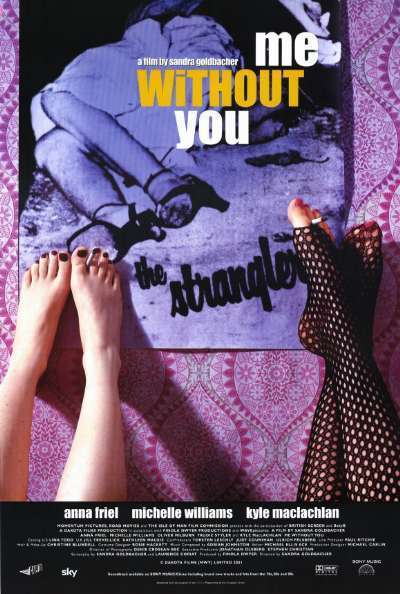

Marina and Holly's childhood friendship evolves into a toxic relationship when they grow up, but they still remain close because even when they're hurting each other, there's no one else they'd rather hurt. Ever had a friend like that? Although Marina is more neurotic and Holly is more the victim, maybe it's because they like it that way. If Holly knew the whole story of how Marina betrays her, she'd be devastated--but then, of course, she doesn't.

"Me Without You" has a bracing truth that's refreshing after the phoniness of female-bonding pictures like "Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood." It doesn't mindlessly celebrate female friendship, but looks at it with a level gaze. If Holly and Marina remain friends despite everything--well, maybe it would be a shame to throw away all that history.

Sandra Goldbacher's film begins in London in 1974 and continues for another 20 years, paying close attention to changing fashions in clothing, music and makeup, while not making too big a point of it. We meet Holly (Michelle Williams of "Dawson's Creek") and Marina (Anna Friel) as adolescents who seal their friendship by placing treasures in a box and hiding it (there is a law requiring all female friends to perform this ritual in the movies). We meet their parents. Marina has a mother who fancies herself a sexpot and is a little drunk all day long, and a father who is, understandably, distant. Holly comes from a Jewish family that is warm but not especially supportive; she learns from her mother that she is more clever than pretty, and is not clever enough to figure out that she's pretty, too.

Marina has a brother named Nat (Oliver Milburn) who Holly has always been in love with. He is a decent sort and likes Holly, too, and one night during their hippie party phase he makes love to her, but this is not on Marina's agenda and she destroys a crucial letter that could have changed everything.

Another rivalry over a male takes place at college, when both women fall for a handsome dweeb American lecturer named Daniel (Kyle MacLachlan). And here the movie does something that few female-bonding pictures have the nerve to do, and introduces a fully formed, fascinating male. In a superbly modulated performance by MacLachlan, Daniel comes across as a man who can easily be tempted but not easily secured. He's willing to be seduced but is frightened of commitment; his posture is always that of the male prepared to back away and apologize at the slightest offense. He has a highly developed line in chit-chat, quoting all the best poets, and Holly is deceived by him while the more cynical Marina strip-mines him and moves on.

What's fascinating about the Daniel character is that he illustrates how men are not always the villains in unfaithful relationships, but sometimes simply the pawns of female agendas. Daniel gives both women what they want, and they want it more than he wants to give it. So although he appears to be a two-timer, he's more of a two-time loser. Rare, to see a character portrayed in this depth instead of simply being used as a plot ploy.

Michelle Williams is the surprise. I am not a student of "Dawson's Creek," but I know she uses an American accent on it, and here, like Renee Zellweger in "Bridget Jones's Diary," she crosses the Atlantic, produces a perfectly convincing British accent, and is cuddly and smart both at once. Anna Friel, as Marina, has a tricky role because she is only ostensibly the sexy, world-wise woman, and in fact is closer to her insecure mother. What eats at her is that in the long run Holly is more appealing to men, and it has nothing to do with hair or necklines.

The movie isn't entirely free of cliches (the secret treasure box, dredged up from a pond after decades, of course is still intact). But the screenplay, by Goldbacher and Laurence Coriat, plays as if the authors have based it on their observations of life, not of movies. There is ultimately a species of happy ending, although you realize it represents maturity and weariness more than victory. The struggles of the teens and 20s are so fraught, so passionate, so seemingly desperate, that when you grow older and learn balance and perspective, there's a bittersweet sense of loss. In years to come, Marina and Holly may reflect that they were never happier than when they were making each other miserable.