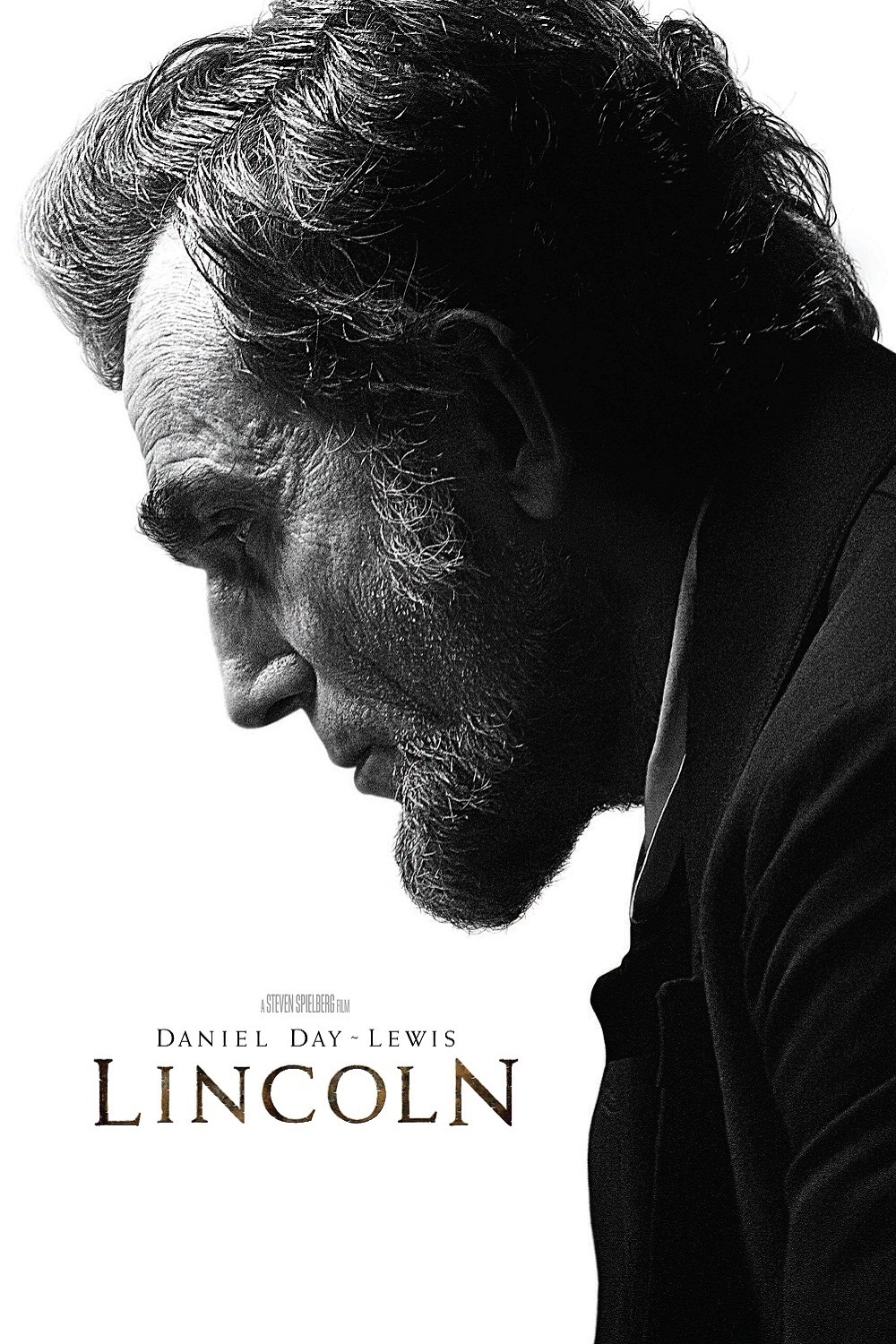

I've rarely been more aware than during Steven Spielberg's "Lincoln" that Abraham Lincoln was a plain-spoken, practical, down-to-earth man from the farmlands of Kentucky, Indiana and Illinois. He had less than a year of formal education and taught himself through his hungry reading of great books. I still recall from a childhood book the image of him taking a piece of charcoal and working out mathematics by writing on the back of a shovel.

Lincoln lacked social polish but he had great intelligence and knowledge of human nature. The hallmark of the man, performed so powerfully by Daniel Day-Lewis in "Lincoln," is calm self-confidence, patience and a willingness to play politics in a realistic way. The film focuses on the final months of Lincoln's life, including the passage of the 13th Amendment ending slavery, the surrender of the Confederacy and his assassination. Rarely has a film attended more carefully to the details of politics.

Lincoln believed slavery was immoral, but he also considered the 13th Amendment a masterstroke in cutting away the financial foundations of the Confederacy. In the film, the passage of the amendment is guided by William Seward (David Strathairn), his secretary of state, and by Rep. Thaddeus Stevens (Tommy Lee Jones), the most powerful abolitionist in the House. Neither these nor any other performances in the film depend on self-conscious histrionics; Jones in particular portrays a crafty codger with some secret hiding places in his heart.

The capital city of Washington is portrayed here as roughshod gathering of politicians on the make. The images by Janusz Kaminski, Spielberg's frequent cinematographer, use earth tones and muted indoor lighting. The White House is less a temple of state than a gathering place for wheelers and dealers. This ambience reflects the descriptions in Gore Vidal's historical novel "Lincoln," although the political and personal details in Tony Kushner's concise, revealing dialogue is based on "Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln" by Doris Kearns Goodwin. The book is well-titled. This is a film not about an icon of history, but about a president who was scorned by some of his political opponents as just a hayseed from the backwoods.

Lincoln is not above political vote buying. He offers jobs, promotions, titles and pork barrel spending. He isn't even slightly reluctant to employ the low-handed tactics of his chief negotiators (Tim Blake Nelson, James Spader, John Hawkes). That's how the game is played, and indeed we may be reminded of the arm-bending used to pass the civil rights legislation by Lyndon B. Johnson, the subject of another biography by Goodwin.

Daniel Day-Lewis, who has a lock on an Oscar nomination, modulates Lincoln. He is soft-spoken, a little hunched, exhausted after the years of war, concerned that no more troops die. He communicates through stories and parables. At his side is his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln (Sally Field, typically sturdy and spunky), who is sometimes seen as a social climber but here is focused as wife and mother. She has already lost one son in the war and fears to lose the other. This boy, Robert Todd Lincoln (Joseph Gordon-Levitt), refuses the privileges of family.

There are some battlefields in "Lincoln" but the only battle scene is at the opening, when the words of the Gettysburg Address are spoken with the greatest possible impact, and not by Lincoln. Kushner also smoothly weaves the wording of the 13th Amendment into the film without making it sound like an obligatory history lesson.

The film ends soon after Lincoln's assassination. I suppose audiences will expect that to be included. There is an earlier shot, when it could have ended, of President Lincoln walking away from the camera after his amendment has been passed. The rest belongs to history.