Abstract

The use of and search for drugs and dietary supplements derived from plants have accelerated in recent years. Ethnopharmacologists, botanists, microbiologists, and natural-products chemists are combing the Earth for phytochemicals and “leads” which could be developed for treatment of infectious diseases. While 25 to 50% of current pharmaceuticals are derived from plants, none are used as antimicrobials. Traditional healers have long used plants to prevent or cure infectious conditions; Western medicine is trying to duplicate their successes. Plants are rich in a wide variety of secondary metabolites, such as tannins, terpenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids, which have been found in vitro to have antimicrobial properties. This review attempts to summarize the current status of botanical screening efforts, as well as in vivo studies of their effectiveness and toxicity. The structure and antimicrobial properties of phytochemicals are also addressed. Since many of these compounds are currently available as unregulated botanical preparations and their use by the public is increasing rapidly, clinicians need to consider the consequences of patients self-medicating with these preparations.

“Eat leeks in March and wild garlic in May, and all the year after the physicians may play.” Traditional Welsh rhyme (230)

“An apple a day keeps the doctor away.” Traditional American rhyme

Finding healing powers in plants is an ancient idea. People on all continents have long applied poultices and imbibed infusions of hundreds, if not thousands, of indigenous plants, dating back to prehistory. There is evidence that Neanderthals living 60,000 years ago in present-day Iraq used plants such as hollyhock (211, 224); these plants are still widely used in ethnomedicine around the world. Historically, therapeutic results have been mixed; quite often cures or symptom relief resulted. Poisonings occurred at a high rate, also. Currently, of the one-quarter to one-half of all pharmaceuticals dispensed in the United States having higher-plant origins, very few are intended for use as antimicrobials, since we have relied on bacterial and fungal sources for these activities. Since the advent of antibiotics in the 1950s, the use of plant derivatives as antimicrobials has been virtually nonexistent.

Clinical microbiologists have two reasons to be interested in the topic of antimicrobial plant extracts. First, it is very likely that these phytochemicals will find their way into the arsenal of antimicrobial drugs prescribed by physicians; several are already being tested in humans (see below). It is reported that, on average, two or three antibiotics derived from microorganisms are launched each year (43). After a downturn in that pace in recent decades, the pace is again quickening as scientists realize that the effective life span of any antibiotic is limited. Worldwide spending on finding new anti-infective agents (including vaccines) is expected to increase 60% from the spending levels in 1993 (7). New sources, especially plant sources, are also being investigated. Second, the public is becoming increasingly aware of problems with the overprescription and misuse of traditional antibiotics. In addition, many people are interested in having more autonomy over their medical care. A multitude of plant compounds (often of unreliable purity) is readily available over-the-counter from herbal suppliers and natural-food stores, and self-medication with these substances is commonplace. The use of plant extracts, as well as other alternative forms of medical treatments, is enjoying great popularity in the late 1990s. Earlier in this decade, approximately one-third of people surveyed in the United States used at least one “unconventional” therapy during the previous year (60). It was reported that in 1996, sales of botanical medicines increased 37% over 1995 (116). It is speculated that the American public may be reacting to overprescription of sometimes toxic drugs, just as their predecessors of the 19th century (see below) reacted to the overuse of bleeding, purging, and calomel (248).

Brief History

It is estimated that there are 250,000 to 500,000 species of plants on Earth (25). A relatively small percentage (1 to 10%) of these are used as foods by both humans and other animal species. It is possible that even more are used for medicinal purposes (146). Hippocrates (in the late fifth century B.C.) mentioned 300 to 400 medicinal plants (195). In the first century A.D., Dioscorides wrote De Materia Medica, a medicinal plant catalog which became the prototype for modern pharmacopoeias. The Bible offers descriptions of approximately 30 healing plants. Indeed, frankincense and myrrh probably enjoyed their status of great worth due to their medicinal properties. Reported to have antiseptic properties, they were even employed as mouthwashes. The fall of ancient civilizations forestalled Western advances in the understanding of medicinal plants, with much of the documentation of plant pharmaceuticals being destroyed or lost (211). During the Dark Ages, the Arab world continued to excavate their own older works and to build upon them. Of course, Asian cultures were also busy compiling their own pharmacopoeia. In the West, the Renaissance years saw a revival of ancient medicine, which was built largely on plant medicinals.

North America’s history of plant medicinal use follows two strands—their use by indigenous cultures (Native Americans), dating from prehistory (243), and an “alternative” movement among Americans of European origin, beginning in the 19th century. Native American use of plant medicinals has been reviewed extensively in a series of articles by Moerman (146). He reported that while 1,625 species of plants have been used by various Native American groups as food, 2,564 have found use as drugs (116). According to his calculations, this leaves approximately 18,000 species of plants which were used for neither food nor drugs. Speculations as to how and why a selected number of plant species came into use for either food or drugs is fascinating but outside the scope of this review.

Among Europeans living in the New World, the use of botanicals was a reaction against invasive or toxic mainstream medicinal practices of the day. No less a luminary than Oliver Wendell Holmes noted that medical treatments in the 1800s could be dangerous and ineffective. Examples include the use of mercury baths in London “barber shops” to treat syphilis and dangerous hallucinogens as a tuberculosis “cure.” In 1861 Holmes wrote, “If the whole materia medica as now used could be sunk to the bottom of the sea, it would be all the better for mankind—and all the worse for the fishes” (92). In 1887, alternative practitioners compiled their own catalogs, notably the Homeopathic Pharmacopoeia of the United States.

Mainstream medicine is increasingly receptive to the use of antimicrobial and other drugs derived from plants, as traditional antibiotics (products of microorganisms or their synthesized derivatives) become ineffective and as new, particularly viral, diseases remain intractable to this type of drug. Another driving factor for the renewed interest in plant antimicrobials in the past 20 years has been the rapid rate of (plant) species extinction (131). There is a feeling among natural-products chemists and microbiologists alike that the multitude of potentially useful phytochemical structures which could be synthesized chemically is at risk of being lost irretrievably (25). There is a scientific discipline known as ethnobotany (or ethnopharmacology), whose goal is to utilize the impressive array of knowledge assembled by indigenous peoples about the plant and animal products they have used to maintain health (77, 182, 203, 234). Lastly, the ascendancy of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) has spurred intensive investigation into the plant derivatives which may be effective, especially for use in underdeveloped nations with little access to expensive Western medicines. (For a comprehensive review of the search for new anti-HIV agents, see reference 51.)

This review describes the current state of plant antimicrobials in the United States, ranging from extracts commonly in use, largely by the lay community, to substances being prospected and tested by researchers and clinicians. Also, compounds potentially effective in treating HIV infections, which are being sought far and wide for probable use in North America, are also addressed. An attempt is also made to summarize the current state of knowledge of relatively undefined herbal products, since clinicians in this country will encounter their use among patients in the United States. This review does not address the worldwide use of plants as medicinals, but, rather, it focuses on plants and their extracts currently in use in North America. Only phytochemicals reported to have anti-infective properties are examined. The many plants used as immune system boosters are outside the purview of this review. Within these boundaries, reports cited in the peer-reviewed literature are given heaviest emphasis. Detailed descriptions of individual plant-derived medications can be found in the first edition of the Physician’s Desk Reference for Herbal Medicines, published by Medical Economics Company in 1998.

MAJOR GROUPS OF ANTIMICROBIAL COMPOUNDS FROM PLANTS

Plants have an almost limitless ability to synthesize aromatic substances, most of which are phenols or their oxygen-substituted derivatives (76). Most are secondary metabolites, of which at least 12,000 have been isolated, a number estimated to be less than 10% of the total (195). In many cases, these substances serve as plant defense mechanisms against predation by microorganisms, insects, and herbivores. Some, such as terpenoids, give plants their odors; others (quinones and tannins) are responsible for plant pigment. Many compounds are responsible for plant flavor (e.g., the terpenoid capsaicin from chili peppers), and some of the same herbs and spices used by humans to season food yield useful medicinal compounds (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Plants containing antimicrobial activitya

| Common name | Scientific name | Compound | Class | Activityd | Relative toxicityb | Reference(s)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alfalfa | Medicago sativa | ? | Gram-positive organisms | 2.3 | ||

| Allspice | Pimenta dioica | Eugenol | Essential oil | General | 2.5 | |

| Aloe | Aloe barbadensis, Aloe vera | Latex | Complex mixture | Corynebacterium, Salmonella, Streptococcus, S. aureus | 2.7 | 136 |

| Apple | Malus sylvestris | Phloretin | Flavonoid derivative | General | 3.0 | 101 |

| Ashwagandha | Withania somniferum | Withafarin A | Lactone | Bacteria, fungi | 0.0 | |

| Aveloz | Euphorbia tirucalli | ? | S. aureus | 0.0 | ||

| Bael tree | Aegle marmelos | Essential oil | Terpenoid | Fungi | 179 | |

| Balsam pear | Momordica charantia | ? | General | 1.0 | ||

| Barberry | Berberis vulgaris | Berberine | Alkaloid | Bacteria, protozoa | 2.0 | 140, 163 |

| Basil | Ocimum basilicum | Essential oils | Terpenoids | Salmonella, bacteria | 2.5 | 241 |

| Bay | Laurus nobilis | Essential oils | Terpenoids | Bacteria, fungi | 0.7 | |

| Betel pepper | Piper betel | Catechols, eugenol | Essential oils | General | 1.0 | |

| Black pepper | Piper nigrum | Piperine | Alkaloid | Fungi, Lactobacillus, Micrococcus, E. coli, E. faecalis | 1.0 | 78 |

| Blueberry | Vaccinium spp. | Fructose | Monosaccharide | E. coli | 158 | |

| Brazilian pepper tree | Schinus terebinthifolius | Terebinthone | Terpenoids | General | 1.0 | |

| Buchu | Barosma setulina | Essential oil | Terpenoid | General | 2.0 | |

| Burdock | Arctium lappa | Polyacetylene, tannins, terpenoids | Bacteria, fungi, viruses | 2.3 | ||

| Buttercup | Ranunculus bulbosus | Protoanemonin | Lactone | General | 2.0 | |

| Caraway | Carum carvi | Coumarins | Bacteria, fungi, viruses | 24, 26, 83, 193 | ||

| Cascara sagrada | Rhamnus purshiana | Tannins | Polyphenols | Viruses, bacteria, fungi | 1.0 | |

| Anthraquinone | ||||||

| Cashew | Anacardium pulsatilla | Salicylic acids | Polyphenols | P. acnes | ||

| Bacteria, fungi | 91 | |||||

| Castor bean | Ricinus communis | ? | General | 0.0 | ||

| Ceylon cinnamon | Cinnamomum verum | Essential oils, others | Terpenoids, tannins | General | 2.0 | |

| Chamomile | Matricaria chamomilla | Anthemic acid | Phenolic acid | M. tuberculosis, S. typhimurium, S. aureus, helminths | 2.3 | 26, 83, 193 |

| — | Coumarins | Viruses | 24 | |||

| Chapparal | Larrea tridentata | Nordihydroguaiaretic acid | Lignan | Skin bacteria | 2.0 | |

| Chili peppers, paprika | Capsicum annuum | Capsaicin | Terpenoid | Bacteria | 2.0 | 42, 107 |

| Clove | Syzygium aromaticum | Eugenol | Terpenoid | General | 1.7 | |

| Coca | Erythroxylum coca | Cocaine | Alkaloid | Gram-negative and -positive cocci | 0.5 | |

| Cockle | Agrostemma githago | ? | General | 1.0 | ||

| Coltsfoot | Tussilago farfara | ? | General | 2.0 | ||

| Coriander, cilantro | Coriandrum sativum | ? | Bacteria, fungi | |||

| Cranberry | Vaccinium spp. | Fructose | Monosaccharide | Bacteria | 17, 158, 159 | |

| Other | ||||||

| Dandelion | Taraxacum officinale | ? | C. albicans, S. cerevisiae | 2.7 | ||

| Dill | Anethum graveolens | Essential oil | Terpenoid | Bacteria | 3.0 | |

| Echinacea | Echinaceae angustifolia | ? | General | 153 | ||

| Eucalyptus | Eucalyptus globulus | Tannin | Polyphenol | Bacteria, viruses | 1.5 | |

| — | Terpenoid | |||||

| Fava bean | Vicia faba | Fabatin | Thionin | Bacteria | ||

| Gamboge | Garcinia hanburyi | Resin | General | 0.5 | ||

| Garlic | Allium sativum | Allicin, ajoene | Sulfoxide | General | 150, 187, 188 | |

| Sulfated terpenoids | 250 | |||||

| Ginseng | Panax notoginseng | Saponins | E. coli, Sporothrix schenckii, Staphylococcus, Trichophyton | 2.7 | ||

| Glory lily | Gloriosa superba | Colchicine | Alkaloid | General | 0.0 | |

| Goldenseal | Hydrastis canadensis | Berberine, hydrastine | Alkaloids | Bacteria, Giardia duodenale, trypanosomes | 2.0 | 73 |

| Plasmodia | 163 | |||||

| Gotu kola | Centella asiatica | Asiatocoside | Terpenoid | M. leprae | 1.7 | |

| Grapefruit peel | Citrus paradisa | Terpenoid | Fungi | 209 | ||

| Green tea | Camellia sinensis | Catechin | Flavonoid | General | 2.0 | |

| Shigella | 235 | |||||

| Vibrio | 226 | |||||

| S. mutans | 166 | |||||

| Viruses | 113 | |||||

| Harmel, rue | Peganum harmala | ? | Bacteria, fungi | 1.0 | ||

| Hemp | Cannabis sativa | β-Resercyclic acid | Organic acid | Bacteria and viruses | 1.0 | |

| Henna | Lawsonia inermis | Gallic acid | Phenolic | S. aureus | 1.5 | |

| Hops | Humulus lupulus | Lupulone, humulone | Phenolic acids | General | 2.3 | |

| — | (Hemi)terpenoids | |||||

| Horseradish | Armoracia rusticana | Terpenoids | General | |||

| Hyssop | Hyssopus officinalis | — | Terpenoids | Viruses | ||

| (Japanese) herb | Rabdosia trichocarpa | Trichorabdal A | Terpene | Helicobacter pylori | 108 | |

| Lantana | Lantana camara | ? | General | 1.0 | ||

| — | Lawsonia | Lawsone | Quinone | M. tuberculosis | — | |

| Lavender-cotton | Santolina chamaecyparissus | ? | Gram-positive bacteria, Candida | 1.0 | 213 | |

| Legume (West Africa) | Millettia thonningii | Alpinumisoflavone | Flavone | Schistosoma | 175 | |

| Lemon balm | Melissa officinalis | Tannins | Polyphenols | Viruses | 245 | |

| Lemon verbena | Aloysia triphylla | Essential oil | Terpenoid | Ascaris | 1.5 | |

| ? | E. coli, M. tuberculosis, S. aureus | |||||

| Licorice | Glycyrrhiza glabra | Glabrol | Phenolic alcohol | S. aureus, M. tuberculosis | 2.0 | |

| Lucky nut, yellow | Thevetia peruviana | ? | Plasmodium | 0.0 | ||

| Mace, nutmeg | Myristica fragrans | ? | General | 1.5 | ||

| Marigold | Calendula officinalis | ? | Bacteria | 2.7 | ||

| Mesquite | Prosopis juliflora | ? | General | 1.5 | ||

| Mountain tobacco | Arnica montana | Helanins | Lactones | General | 2.0 | |

| Oak | Quercus rubra | Tannins | Polyphenols | |||

| Quercetin (available commercially) | Flavonoid | 113 | ||||

| Olive oil | Olea europaea | Hexanal | Aldehyde | General | 120 | |

| Onion | Allium cepa | Allicin | Sulfoxide | Bacteria, Candida | 239 | |

| Orange peel | Citrus sinensis | ? | Terpenoid | Fungi | 209 | |

| Oregon grape | Mahonia aquifolia | Berberine | Alkaloid | Plasmodium | 2.0 | 163 |

| Trypansomes, general | 73 | |||||

| Pao d’arco | Tabebuia | Sesquiterpenes | Terpenoids | Fungi | 1.0 | |

| Papaya | Carica papaya | Latex | Mix of terpenoids, organic acids, alkaloids | General | 3.0 | 34, 168, 191 |

| Pasque-flower | Anemone pulsatilla | Anemonins | Lactone | Bacteria | 0.5 | |

| Peppermint | Mentha piperita | Menthol | Terpenoid | General | ||

| Periwinkle | Vinca minor | Reserpine | Alkaloid | General | 1.5 | |

| Peyote | Lophophora williamsii | Mescaline | Alkaloid | General | 1.5 | |

| Poinsettia | Euphorbia pulcherrima | ? | General | 0.0 | ||

| Poppy | Papaver somniferum | Opium | Alkaloids and others | General | 0.5 | |

| Potato | Solanum tuberosum | ? | Bacteria, fungi | 2.0 | ||

| Prostrate knotweed | Polygonum aviculare | ? | General | 2.0 | ||

| Purple prairie clover | Petalostemum | Petalostemumol | Flavonol | Bacteria, fungi | 100 | |

| Quinine | Cinchona sp. | Quinine | Alkaloid | Plasmodium spp. | 2.0 | |

| Rauvolfia, chandra | Rauvolfia serpentina | Reserpine | Alkaloid | General | 1.0 | |

| Rosemary | Rosmarinus officinalis | Essential oil | Terpenoid | General | 2.3 | |

| Sainfoin | Onobrychis viciifolia | Tannins | Polyphenols | Ruminal bacteria | 105 | |

| Sassafras | Sassafras albidum | ? | Helminths | 2.0 | ||

| Savory | Satureja montana | Carvacrol | Terpenoid | General | 2.0 | 6 |

| Senna | Cassia angustifolia | Rhein | Anthraquinone | S. aureus | 2.0 | |

| Smooth hydrangea, seven barks | Hydrangea arborescens | ? | General | 2.3 | ||

| Snakeplant | Rivea corymbosa | ? | General | 1.0 | ||

| St. John’s wort | Hypericum perforatum | Hypericin, others | Anthraquinone | General | 1.7 | |

| Sweet flag, calamus | Acorus calamus | ? | Enteric bacteria | 0.7 | ||

| Tansy | Tanacetum vulgare | Essential oils | Terpenoid | Helminths, bacteria | 2.0 | |

| Tarragon | Artemisia dracunculus | Caffeic acids, tannins | Terpenoid | Viruses, helminths | 2.5 | |

| Polyphenols | 245 | |||||

| Thyme | Thymus vulgaris | Caffeic acid | Terpenoid | Viruses, bacteria, fungi | 2.5 | |

| Thymol | Phenolic alcohol | |||||

| Tannins | Polyphenols | |||||

| — | Flavones | |||||

| Tree bard | Podocarpus nagi | Totarol | Flavonol | P. acnes, other gram-positive bacteria | 123 | |

| Nagilactone | Lactone | Fungi | 121 | |||

| 122 | ||||||

| Tua-Tua | Jatropha gossyphiifolia | ? | General | 0.0 | ||

| Turmeric | Curcuma longa | Curcumin | Terpenoids | Bacteria, protozoa | 14 | |

| Turmeric oil | ||||||

| Valerian | Valeriana officinalis | Essential oil | Terpenoid | General | 2.7 | |

| Willow | Salix alba | Salicin | Phenolic glucoside | |||

| Tannins | Polyphenols | |||||

| Essential oil | Terpenoid | |||||

| Wintergreen | Gaultheria procumbens | Tannins | Polyphenols | General | 1.0 | |

| Woodruff | Galium odoratum | — | Coumarin | General | 3.0 | 26, 83, 193 |

| Viruses | 24 | |||||

| Yarrow | Achillea millefolium | ? | Viruses, helminths | 2.3 | ||

| Yellow dock | Rumex crispus | ? | E. coli, Salmonella, Staphylococcus | 1.0 |

Plants with activity only against HIV are listed in Table 6.

0, very safe; 3, very toxic. Data from reference 58.

“General” denotes activity against multiple types of microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, fungi, and protozoa), and “bacteria” denotes activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria.

Useful antimicrobial phytochemicals can be divided into several categories, described below and summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Major classes of antimicrobial compounds from plants

| Class | Subclass | Example(s) | Mechanism | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenolics | Simple phenols | Catechol | Substrate deprivation | 174 |

| Epicatechin | Membrane disruption | 226 | ||

| Phenolic acids | Cinnamic acid | 66 | ||

| Quinones | Hypericin | Bind to adhesins, complex with cell wall, inactivate enzymes | 58, 114 | |

| Flavonoids | Chrysin | Bind to adhesins | 175, 182 | |

| Flavones | Complex with cell wall | |||

| Abyssinone | Inactivate enzymes | 32, 219 | ||

| Inhibit HIV reverse transcriptase | 164 | |||

| Flavonols | Totarol | ? | 122 | |

| Tannins | Ellagitannin | Bind to proteins | 196, 210 | |

| Bind to adhesins | 192 | |||

| Enzyme inhibition | 87, 33, 35 | |||

| Substrate deprivation | ||||

| Complex with cell wall | ||||

| Membrane disruption | ||||

| Metal ion complexation | ||||

| Coumarins | Warfarin | Interaction with eucaryotic DNA (antiviral activity) | 26, 95, 113, 251 | |

| Terpenoids, essential oils | Capsaicin | Membrane disruption | 42 | |

| Alkaloids | Berberine | Intercalate into cell wall and/or DNA | 15, 34, 73, 94 | |

| Piperine | ||||

| Lectins and polypeptides | Mannose-specific agglutinin | Block viral fusion or adsorption | 145, 253 | |

| Fabatin | Form disulfide bridges | |||

| Polyacetylenes | 8S-Heptadeca-2(Z),9(Z)-diene-4,6-diyne-1,8-diol | ? | 62 |

Phenolics and Polyphenols

Simple phenols and phenolic acids.

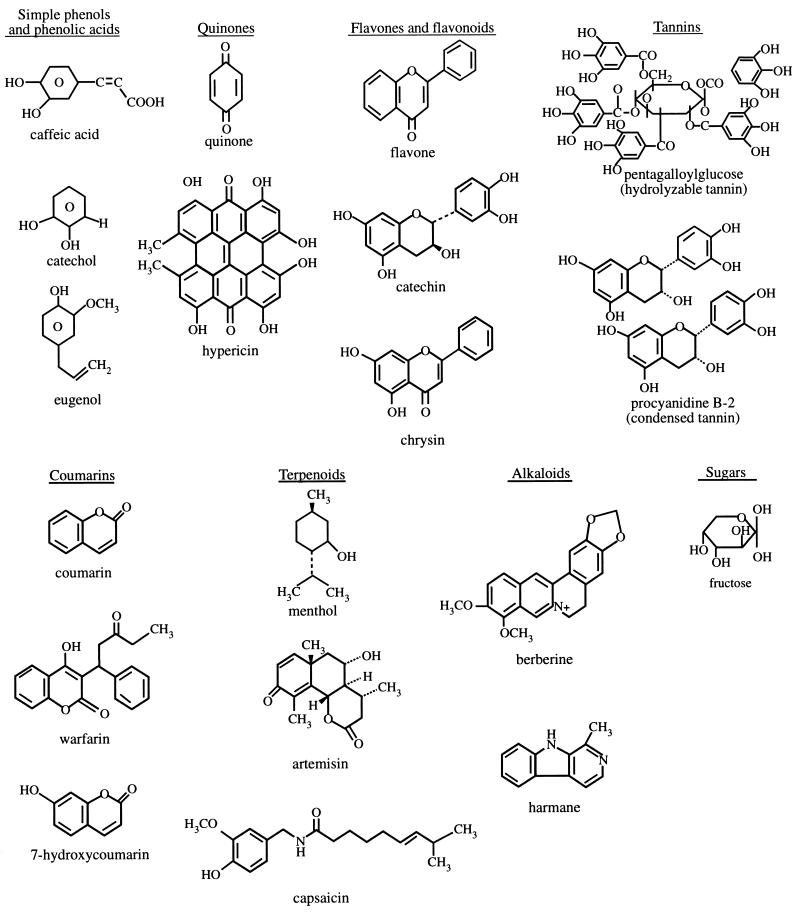

Some of the simplest bioactive phytochemicals consist of a single substituted phenolic ring. Cinnamic and caffeic acids are common representatives of a wide group of phenylpropane-derived compounds which are in the highest oxidation state (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Structures of common antimicrobial plant chemicals.

The common herbs tarragon and thyme both contain caffeic acid, which is effective against viruses (245), bacteria (31, 224), and fungi (58).

Catechol and pyrogallol both are hydroxylated phenols, shown to be toxic to microorganisms. Catechol has two −OH groups, and pyrogallol has three. The site(s) and number of hydroxyl groups on the phenol group are thought to be related to their relative toxicity to microorganisms, with evidence that increased hydroxylation results in increased toxicity (76). In addition, some authors have found that more highly oxidized phenols are more inhibitory (192, 231). The mechanisms thought to be responsible for phenolic toxicity to microorganisms include enzyme inhibition by the oxidized compounds, possibly through reaction with sulfhydryl groups or through more nonspecific interactions with the proteins (137).

Phenolic compounds possessing a C3 side chain at a lower level of oxidation and containing no oxygen are classified as essential oils and often cited as antimicrobial as well. Eugenol is a well-characterized representative found in clove oil (Fig. 1). Eugenol is considered bacteriostatic against both fungi (58) and bacteria (224).

Quinones.

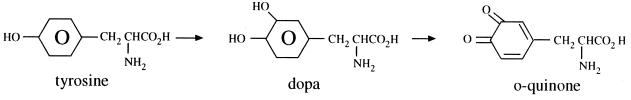

Quinones are aromatic rings with two ketone substitutions (Fig. 1). They are ubiquitous in nature and are characteristically highly reactive. These compounds, being colored, are responsible for the browning reaction in cut or injured fruits and vegetables and are an intermediate in the melanin synthesis pathway in human skin (194). Their presence in henna gives that material its dyeing properties (69). The switch between diphenol (or hydroquinone) and diketone (or quinone) occurs easily through oxidation and reduction reactions. The individual redox potential of the particular quinone-hydroquinone pair is very important in many biological systems; witness the role of ubiquinone (coenzyme Q) in mammalian electron transport systems. Vitamin K is a complex naphthoquinone. Its antihemorrhagic activity may be related to its ease of oxidation in body tissues (85). Hydroxylated amino acids may be made into quinones in the presence of suitable enzymes, such as a polyphenoloxidase (233). The reaction for the conversion of tyrosine to quinone is shown in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

Reaction for the conversion of tyrosine to quinone.

In addition to providing a source of stable free radicals, quinones are known to complex irreversibly with nucleophilic amino acids in proteins (210), often leading to inactivation of the protein and loss of function. For that reason, the potential range of quinone antimicrobial effects is great. Probable targets in the microbial cell are surface-exposed adhesins, cell wall polypeptides, and membrane-bound enzymes. Quinones may also render substrates unavailable to the microorganism. As with all plant-derived antimicrobials, the possible toxic effects of quinones must be thoroughly examined.

Kazmi et al. (112) described an anthraquinone from Cassia italica, a Pakistani tree, which was bacteriostatic for Bacillus anthracis, Corynebacterium pseudodiphthericum, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and bactericidal for Pseudomonas pseudomalliae. Hypericin, an anthraquinone from St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum), has received much attention in the popular press lately as an antidepressant, and Duke reported in 1985 that it had general antimicrobial properties (58).

Flavones, flavonoids, and flavonols.

Flavones are phenolic structures containing one carbonyl group (as opposed to the two carbonyls in quinones) (Fig. 1). The addition of a 3-hydroxyl group yields a flavonol (69). Flavonoids are also hydroxylated phenolic substances but occur as a C6-C3 unit linked to an aromatic ring. Since they are known to be synthesized by plants in response to microbial infection (56), it should not be surprising that they have been found in vitro to be effective antimicrobial substances against a wide array of microorganisms. Their activity is probably due to their ability to complex with extracellular and soluble proteins and to complex with bacterial cell walls, as described above for quinones. More lipophilic flavonoids may also disrupt microbial membranes (229).

Catechins, the most reduced form of the C3 unit in flavonoid compounds, deserve special mention. These flavonoids have been extensively researched due to their occurrence in oolong green teas. It was noticed some time ago that teas exerted antimicrobial activity (227) and that they contain a mixture of catechin compounds. These compounds inhibited in vitro Vibrio cholerae O1 (25), Streptococcus mutans (23, 185, 186, 228), Shigella (235), and other bacteria and microorganisms (186, 224). The catechins inactivated cholera toxin in Vibrio (25) and inhibited isolated bacterial glucosyltransferases in S. mutans (151), possibly due to complexing activities described for quinones above. This latter activity was borne out in in vivo tests of conventional rats. When the rats were fed a diet containing 0.1% tea catechins, fissure caries (caused by S. mutans) was reduced by 40% (166).

Flavonoid compounds exhibit inhibitory effects against multiple viruses. Numerous studies have documented the effectiveness of flavonoids such as swertifrancheside (172), glycyrrhizin (from licorice) (242), and chrysin (48) against HIV. More than one study has found that flavone derivatives are inhibitory to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) (21, 111). Kaul et al. (111) provide a summary of the activities and modes of action of quercetin, naringin, hesperetin, and catechin in in vitro cell culture monolayers. While naringin was not inhibitory to herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1), poliovirus type 1, parainfluenza virus type 3, or RSV, the other three flavonoids were effective in various ways. Hesperetin reduced intracellular replication of all four viruses; catechin inhibited infectivity but not intracellular replication of RSV and HSV-1; and quercetin was universally effective in reducing infectivity. The authors propose that small structural differences in the compounds are critical to their activity and pointed out another advantage of many plant derivatives: their low toxic potential. The average Western daily diet contains approximately 1 g of mixed flavonoids (124); pharmacologically active concentrations are not likely to be harmful to human hosts.

An isoflavone found in a West African legume, alpinumisoflavone, prevents schistosomal infection when applied topically (175). Phloretin, found in certain serovars of apples, may have activity against a variety of microorganisms (101). Galangin (3,5,7-trihydroxyflavone), derived from the perennial herb Helichrysum aureonitens, seems to be a particularly useful compound, since it has shown activity against a wide range of gram-positive bacteria as well as fungi (2) and viruses, in particular HSV-1 and coxsackie B virus type 1 (145).

Delineation of the possible mechanism of action of flavones and flavonoids is hampered by conflicting findings. Flavonoids lacking hydroxyl groups on their β-rings are more active against microorganisms than are those with the −OH groups (38); this finding supports the idea that their microbial target is the membrane. Lipophilic compounds would be more disruptive of this structure. However, several authors have also found the opposite effect; i.e., the more hydroxylation, the greater the antimicrobial activity (189). This latter finding reflects the similar result for simple phenolics (see above). It is safe to say that there is no clear predictability for the degree of hydroxylation and toxicity to microorganisms.

Tannins.

“Tannin” is a general descriptive name for a group of polymeric phenolic substances capable of tanning leather or precipitating gelatin from solution, a property known as astringency. Their molecular weights range from 500 to 3,000 (87), and they are found in almost every plant part: bark, wood, leaves, fruits, and roots (192). They are divided into two groups, hydrolyzable and condensed tannins. Hydrolyzable tannins are based on gallic acid, usually as multiple esters with d-glucose, while the more numerous condensed tannins (often called proanthocyanidins) are derived from flavonoid monomers (Fig. 1). Tannins may be formed by condensations of flavan derivatives which have been transported to woody tissues of plants. Alternatively, tannins may be formed by polymerization of quinone units (76). This group of compounds has received a great deal of attention in recent years, since it was suggested that the consumption of tannin-containing beverages, especially green teas and red wines, can cure or prevent a variety of ills (198).

Many human physiological activities, such as stimulation of phagocytic cells, host-mediated tumor activity, and a wide range of anti-infective actions, have been assigned to tannins (87). One of their molecular actions is to complex with proteins through so-called nonspecific forces such as hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic effects, as well as by covalent bond formation (87, 210). Thus, their mode of antimicrobial action, as described in the section on quinones (see above), may be related to their ability to inactivate microbial adhesins, enzymes, cell envelope transport proteins, etc. They also complex with polysaccharide (247). The antimicrobial significance of this particular activity has not been explored. There is also evidence for direct inactivation of microorganisms: low tannin concentrations modify the morphology of germ tubes of Crinipellis perniciosa (33). Tannins in plants inhibit insect growth (196) and disrupt digestive events in ruminal animals (35).

Scalbert (192) reviewed the antimicrobial properties of tannins in 1991. He listed 33 studies which had documented the inhibitory activities of tannins up to that point. According to these studies, tannins can be toxic to filamentous fungi, yeasts, and bacteria. Condensed tannins have been determined to bind cell walls of ruminal bacteria, preventing growth and protease activity (105). Although this is still speculative, tannins are considered at least partially responsible for the antibiotic activity of methanolic extracts of the bark of Terminalia alata found in Nepal (221). This activity was enhanced by UV light activation (320 to 400 nm at 5 W/m2 for 2 h). At least two studies have shown tannins to be inhibitory to viral reverse transcriptases (111, 155).

Coumarins.

Coumarins are phenolic substances made of fused benzene and α-pyrone rings (161). They are responsible for the characteristic odor of hay. As of 1996, at least 1,300 had been identified (95). Their fame has come mainly from their antithrombotic (223), anti-inflammatory (177), and vasodilatory (152) activities. Warfarin is a particularly well-known coumarin which is used both as an oral anticoagulant and, interestingly, as a rodenticide (113). It may also have antiviral effects (24). Coumarins are known to be highly toxic in rodents (232) and therefore are treated with caution by the medical community. However, recent studies have shown a “pronounced species-dependent metabolism” (244), so that many in vivo animal studies cannot be extrapolated to humans. It appears that toxic coumarin derivatives may be safely excreted in the urine in humans (244).

Several other coumarins have antimicrobial properties. R. D. Thornes, working at the Boston Lying-In Hospital in 1954, sought an agent to treat vaginal candidiasis in his pregnant patients. Coumarin was found in vitro to inhibit Candida albicans. (During subsequent in vivo tests on rabbits, the coumarin-spiked water supply was inadvertently given to all the animals in the research facility and was discovered to be a potent contraceptive agent when breeding programs started to fail [225].) Its estrogenic effects were later described (206).

As a group, coumarins have been found to stimulate macrophages (37), which could have an indirect negative effect on infections. More specifically, coumarin has been used to prevent recurrences of cold sores caused by HSV-1 in humans (24) but was found ineffective against leprosy (225). Hydroxycinnamic acids, related to coumarins, seem to be inhibitory to gram-positive bacteria (66). Also, phytoalexins, which are hydroxylated derivatives of coumarins, are produced in carrots in response to fungal infection and can be presumed to have antifungal activity (95). General antimicrobial activity was documented in woodruff (Galium odoratum) extracts (224). All in all, data about specific antibiotic properties of coumarins are scarce, although many reports give reason to believe that some utility may reside in these phytochemicals (26, 83, 193). Further research is warranted.

Terpenoids and Essential Oils

The fragrance of plants is carried in the so called quinta essentia, or essential oil fraction. These oils are secondary metabolites that are highly enriched in compounds based on an isoprene structure (Fig. 1). They are called terpenes, their general chemical structure is C10H16, and they occur as diterpenes, triterpenes, and tetraterpenes (C20, C30, and C40), as well as hemiterpenes (C5) and sesquiterpenes (C15). When the compounds contain additional elements, usually oxygen, they are termed terpenoids.

Terpenoids are synthesized from acetate units, and as such they share their origins with fatty acids. They differ from fatty acids in that they contain extensive branching and are cyclized. Examples of common terpenoids are methanol and camphor (monoterpenes) and farnesol and artemisin (sesquiterpenoids). Artemisin and its derivative α-arteether, also known by the name qinghaosu, find current use as antimalarials (237). In 1985, the steering committee of the scientific working group of the World Health Organization decided to develop the latter drug as a treatment for cerebral malaria.

Terpenenes or terpenoids are active against bacteria (4, 8, 22, 82, 90, 121, 144, 197, 220, 221), fungi (18, 84, 122, 179, 180, 213, 221), viruses (74, 86, 173, 212, 246), and protozoa (78, 237). In 1977, it was reported that 60% of essential oil derivatives examined to date were inhibitory to fungi while 30% inhibited bacteria (39). The triterpenoid betulinic acid is just one of several terpenoids (see below) which have been shown to inhibit HIV. The mechanism of action of terpenes is not fully understood but is speculated to involve membrane disruption by the lipophilic compounds. Accordingly, Mendoza et al. (144) found that increasing the hydrophilicity of kaurene diterpenoids by addition of a methyl group drastically reduced their antimicrobial activity. Food scientists have found the terpenoids present in essential oils of plants to be useful in the control of Listeria monocytogenes (16). Oil of basil, a commercially available herbal, was found to be as effective as 125 ppm chlorine in disinfecting lettuce leaves (241).

Chile peppers are a food item found nearly ubiquitously in many Mesoamerican cultures (44). Their use may reflect more than a desire to flavor foods. Many essential nutrients, such as vitamin C, provitamins A and E, and several B vitamins, are found in chiles (27). A terpenoid constituent, capsaicin, has a wide range of biological activities in humans, affecting the nervous, cardiovascular, and digestive systems (236) as well as finding use as an analgesic (47). The evidence for its antimicrobial activity is mixed. Recently, Cichewicz and Thorpe (42) found that capsaicin might enhance the growth of Candida albicans but that it clearly inhibited various bacteria to differing extents. Although possibly detrimental to the human gastric mucosa, capsaicin is also bactericidal to Helicobacter pylori (106). Another hot-tasting diterpene, aframodial, from a Cameroonian spice, is a broad-spectrum antifungal (18).

The ethanol-soluble fraction of purple prairie clover yields a terpenoid called petalostemumol, which showed excellent activity against Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus and lesser activity against gram-negative bacteria as well as Candida albicans (100). Two diterpenes isolated by Batista et al. (23) were found to be more democratic; they worked well against Staphylococcus aureus, V. cholerae, P. aeruginosa, and Candida spp. When it was observed that residents of Mali used the bark of a tree called Ptelopsis suberosa for the treatment of gastric ulcers, investigators tested terpenoid-containing fractions in 10 rats before and after the rats had ulcers chemically induced. They found that the terpenoids prevented the formation of ulcers and diminished the severity of existent ulcers. Whether this activity was due to antimicrobial action or to protection of the gastric mucosa is not clear (53). Kadota et al. (108) found that trichorabdal A, a diterpene from a Japanese herb, could directly inhibit H. pylori.

Alkaloids

Heterocyclic nitrogen compounds are called alkaloids. The first medically useful example of an alkaloid was morphine, isolated in 1805 from the opium poppy Papaver somniferum (69); the name morphine comes from the Greek Morpheus, god of dreams. Codeine and heroin are both derivatives of morphine. Diterpenoid alkaloids, commonly isolated from the plants of the Ranunculaceae, or buttercup (107) family (15), are commonly found to have antimicrobial properties (163). Solamargine, a glycoalkaloid from the berries of Solanum khasianum, and other alkaloids may be useful against HIV infection (142, 200) as well as intestinal infections associated with AIDS (140). While alkaloids have been found to have microbiocidal effects (including against Giardia and Entamoeba species [78]), the major antidiarrheal effect is probably due to their effects on transit time in the small intestine.

Berberine is an important representative of the alkaloid group. It is potentially effective against trypanosomes (73) and plasmodia (163). The mechanism of action of highly aromatic planar quaternary alkaloids such as berberine and harmane (93) is attributed to their ability to intercalate with DNA (176).

Lectins and Polypeptides

Peptides which are inhibitory to microorganisms were first reported in 1942 (19). They are often positively charged and contain disulfide bonds (253). Their mechanism of action may be the formation of ion channels in the microbial membrane (222, 253) or competitive inhibition of adhesion of microbial proteins to host polysaccharide receptors (202). Recent interest has been focused mostly on studying anti-HIV peptides and lectins, but the inhibition of bacteria and fungi by these macromolecules, such as that from the herbaceous Amaranthus, has long been known (50).

Thionins are peptides commonly found in barley and wheat and consist of 47 amino acid residues (45, 143). They are toxic to yeasts and gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria (65). Thionins AX1 and AX2 from sugar beet are active against fungi but not bacteria (118). Fabatin, a newly identified 47-residue peptide from fava beans, appears to be structurally related to γ-thionins from grains and inhibits E. coli, P. aeruginosa, and Enterococcus hirae but not Candida or Saccharomyces (253).

The larger lectin molecules, which include mannose-specific lectins from several plants (20), MAP30 from bitter melon (128), GAP31 from Gelonium multiflorum (28), and jacalin (64), are inhibitory to viral proliferation (HIV, cytomegalovirus), probably by inhibiting viral interaction with critical host cell components. It is worth emphasizing that molecules and compounds such as these whose mode of action may be to inhibit adhesion will not be detected by using most general plant antimicrobial screening protocols, even with the bioassay-guided fractionation procedures (131, 181) used by natural-products chemists (see below). It is an area of ethnopharmacology which deserves attention, so that initial screens of potentially pharmacologically active plants (described in references 25, 43, and 238) may be made more useful.

Mixtures

The chewing stick is widely used in African countries as an oral hygiene aid (in place of a toothbrush) (156). Chewing sticks come from different species of plants, and within one stick the chemically active component may be heterogeneous (5). Crude extracts of one species used for this purpose, Serindeia werneckei, inhibited the periodontal pathogens Porphyromonas gingivalis and Bacteroides melaninogenicus in vitro (183). The active component of the Nigerian chewing stick (Fagara zanthoxyloides) was found to consist of various alkaloids (157). Whether these compounds, long utilized in developing countries, might find use in the Western world is not yet known.

Papaya (Carica papaya) yields a milky sap, often called a latex, which is a complex mixture of chemicals. Chief among them is papain, a well-known proteolytic enzyme (162). An alkaloid, carpaine, is also present (34). Terpenoids are also present and may contribute to its antimicrobial properties (224). Osato et al. (168) found the latex to be bacteriostatic to B. subtilis, Enterobacter cloacae, E. coli, Salmonella typhi, Staphylococcus aureus, and Proteus vulgaris.

Ayurveda is a type of healing craft practiced in India but not unknown in the United States. Ayurvedic practitioners rely on plant extracts, both “pure” single-plant preparations and mixed formulations. The preparations have lyrical names, such as Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera root) (54), Cauvery 100 (a mixture) (133), and Livo-vet (125). These preparations are used to treat animals as well as humans (125). In addition to their antimicrobial activities, they have been found to have antidiarrheal (134), immunomodulatory (54, 133), anticancer (59), and psychotropic (201) properties. In vivo studies of Abana, an Ayurvedic formulation, found a slight reduction in experimentally induced cardiac arrhythmias in dogs (75). Two microorganisms against which Ayurvedic preparations have activity are Aspergillus spp. (54) and Propionibacterium acnes (170). (The aspergillosis study was performed with mice in vivo, and it is therefore impossible to determine whether the effects are due to the stimulation of macrophage activity in the whole animal rather than to direct antimicrobial effects.)

The toxicity of Ayurvedic preparations has been the subject of some speculation, especially since some of them include metals. Prpic-Majic et al. identified high levels of lead in the blood of adult volunteers who had self-medicated with Ayurvedic medicines (178).

Propolis is a crude extract of the balsam of various trees; it is often called bee glue, since honeybees gather it from the trees. Its chemical composition is very complex: like the latexes described above, terpenoids are present, as well as flavonoids, benzoic acids and esters, and substituted phenolic acids and esters (9). Synthetic cinnamic acids, identical to those from propolis, were found to inhibit hemagglutination activity of influenza virus (199). Amoros et al. found that propolis was active against an acyclovir-resistant mutant of HSV-1, adenovirus type 2, vesicular stomatitis virus, and poliovirus (9). Mixtures of chemicals, such as are found in latex and propolis, may act synergistically. While the flavone and flavonol components were active in isolation against HSV-1, multiple flavonoids incubated simultaneously with the virus were more effective than single chemicals, a possible explanation of why propolis is more effective than its individual compounds (10). Of course, mixtures are more likely to contain toxic constituents, and they must be thoroughly investigated and standardized before approved for use on a large-scale basis in the West.

Other Compounds

Many phytochemicals not mentioned above have been found to exert antimicrobial properties. This review has attempted to focus on reports of chemicals which are found in multiple instances to be active. It should be mentioned, however, that there are reports of antimicrobial properties associated with polyamines (in particular spermidine) (70), isothiocyanates (57, 104), thiosulfinates (215), and glucosides (149, 184).

Polyacetylenes deserve special mention. Estevez-Braun et al. isolated a C17 polyacetylene compound from Bupleurum salicifolium, a plant native to the Canary Islands. The compound, 8S-heptadeca-2(Z),9(Z)-diene-4,6-diyne-1,8-diol, was inhibitory to S. aureus and B. subtilis but not to gram-negative bacteria or yeasts (62). Acetylene compounds and flavonoids from plants traditionally used in Brazil for treatment of malaria fever and liver disorders have also been associated with antimalarial activity (29).

Much has been written about the antimicrobial effects of cranberry juice. Historically, women have been told to drink the juice in order to prevent and even cure urinary tract infections. In the early 1990s, researchers found that the monosaccharide fructose present in cranberry and blueberry juices competitively inhibited the adsorption of pathogenic E. coli to urinary tract epithelial cells, acting as an analogue for mannose (252). Clinical studies have borne out the protective effects of cranberry juice (17). Many fruits contain fructose, however, and researchers are now seeking a second active compound from cranberry juice which contributes to the antimicrobial properties of this juice (252).

EXPERIMENTAL APPROACHES

Extraction Methods

Advice abounds for the amateur herbalist on how to prepare healing compounds from plants and herbs. Water is almost universally the solvent used to extract activity. At home, dried plants can be ingested as teas (plants steeped in hot water) or, rarely, tinctures (plants in alcoholic solutions) or inhaled via steam from boiling suspensions of the parts. Dried plant parts can be added to oils or petroleum jelly and applied externally. Poultices can also be made from concentrated teas or tinctures (30, 224).

Scientific analysis of plant components follows a logical pathway. Plants are collected either randomly or by following leads supplied by local healers in geographical areas where the plants are found (135). Initial screenings of plants for possible antimicrobial activities typically begin by using crude aqueous or alcohol extractions and can be followed by various organic extraction methods. Since nearly all of the identified components from plants active against microorganisms are aromatic or saturated organic compounds, they are most often obtained through initial ethanol or methanol extraction. In fact, many studies avoid the use of aqueous fractionation altogether. The exceptional water-soluble compounds, such as polysaccharides (e.g., starch) and polypeptides, including fabatin (253) and various lectins, are commonly more effective as inhibitors of pathogen (usually virus) adsorption and would not be identified in the screening techniques commonly used. Occasionally tannins and terpenoids will be found in the aqueous phase, but they are more often obtained by treatment with less polar solvents. Table 3 lists examples of extraction solvents and the resultant active fractions reported in recent studies. Compounds which, according to the literature, partition exclusively in particular solvents are indicated in boldface type in the table.

TABLE 3.

Solvents used for active component extractiona

| Water | Ethanol | Methanol | Chloroform | Dichloromethanol | Ether | Acetone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthocyanins (111) | Tannins (204) | Anthocyanins | Terpenoids (18) | Terpenoids (144) | Alkaloids | Flavonols (2) |

| Starches | Polyphenols (151) | Terpenoids (221) | Flavonoids (175) | Terpenoids | ||

| Tannins (192) | Polyacetylenes (29, 62) | Saponins | Coumarins | |||

| Saponins (53) | Flavonol (29, 100) | Tannins (221) | Fatty acids | |||

| Terpenoids | Terpenoids (82) | Xanthoxyllines | ||||

| Polypeptides | Sterols (53) | Totarol (121) | ||||

| Lectins | Alkaloids (103) | Quassinoids (115) | ||||

| Propolis | Lactones (180) | |||||

| Flavones (189, 219) | ||||||

| Phenones (174) | ||||||

| Polyphenols (235) |

Compounds in bold are commonly obtained only in one solvent. References are given in parentheses.

Any part of the plant may contain active components. For instance, the roots of ginseng plants contain the active saponins and essential oils, while eucalyptus leaves are harvested for their essential oils and tannins. Some trees, such as the balsam poplar, yield useful substances in their bark, leaves, and shoots (224).

For alcoholic extractions, plant parts are dried, ground to a fine texture, and then soaked in methanol or ethanol for extended periods. The slurry is then filtered and washed, after which it may be dried under reduced pressure and redissolved in the alcohol to a determined concentration. When water is used for extractions, plants are generally soaked in distilled water, blotted dry, made into a slurry through blending, and then strained or filtered. The filtrate can be centrifuged (approximately 20,000 × g, for 30 min) multiple times for clarification (42, 221). Crude products can then be used in disc diffusion and broth dilution assays to test for antifungal and antibacterial properties and in a variety of assays to screen for antiviral activity, as described below.

Natural-products chemists further purify active chemicals from crude extracts by a variety of methods. Petalostemumol, a flavanol from purple prairie clover, was obtained from the ethanol extract by partitioning between ethyl acetate and water, followed by partitioning between n-hexane and 10% methanol. The methanol fraction was chromatographed and eluted with toluene (100). Terpenoid lactones have been obtained by successive extractions of dried bark with hexane, CHCl3, and methanol, with activity concentrating in the CHCl3 fraction (180). The chemical structures of the purified material can then be analyzed. Techniques for further chemical analysis include chromatography, bioautography, radioimmunoassay, various methods of structure identification, and newer tools such as fast atom bombardment mass spectrometry, tandem mass spectroscopy (181), high-performance liquid chromatography, capillary zone electrophoresis, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and X-ray cystallography (25).

Recently, Eloff (61) examined a variety of extractants for their ability to solubilize antimicrobials from plants, as well as other factors such as their relative ranking as biohazards and the ease of removal of solvent from the fraction. The focus of the study was to provide a more standardized extraction method for the wide variety of researchers working in diverse settings. Although it is not one of the more frequently used extractants in studies published to date, acetone received the highest overall rating. In fact, in a review of 48 articles describing the screening of plant extracts for antimicrobial properties in the most recent years of the Journal of Natural Products, the Journal of Ethnopharmacology, and the International Journal of Pharmacognosy, only one study used acetone as an extractant. Of the solvents listed in Table 3, which are reported in the recent literature with the highest frequency, Eloff ranked them in the order methylene dichloride, methanol, ethanol, and water. Table 4 displays the breakdown of scores for the various solvents studied. The row indicating the number of inhibitors extracted with each solvent points to two implications: first, that most active components are not water soluble, supporting the data reported in Table 3, and second, that the most commonly used solvents (ethanol and methanol, both used as initial extractants in approximately 35% of the studies appearing in the recent literature) may not demonstrate the greatest sensitivity in yielding antimicrobial chemicals on an initial screening. This disparity should be examined as the search for new antimicrobials intensifies.

TABLE 4.

Comparison of extractants on different parameters based on a five-point scale (1 to 5) and with different weights allocated to the different parametersa

| Parameter | Weightb | Acetone

|

Ethanol

|

Methanol

|

MCWc

|

Methylene dichloride

|

Water

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ad | Ce | A | C | A | C | A | C | A | C | A | C | ||

| Quantity extracted | 3 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 3 | 3 | 9 | 9 |

| Rate of extraction | 3 | 12 | 15 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 15 | 15 | 9 | 9 |

| No. of compounds extracted | 5 | 20 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 15 | 5 | 5 |

| No. of inhibitors extracted | 5 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 15 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| Toxicity in bioassay | 4 | 16 | 16 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 16 | 16 |

| Ease of removal | 5 | 20 | 20 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Hazardous to use | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 8 |

| Total | 102 | 102 | 52 | 64 | 71 | 71 | 78 | 83 | 79 | 79 | 47 | 47 | |

Efficacy

In vitro experiments.

(i) Bacteria and fungi.

Initial screening of potential antibacterial and antifungal compounds from plants may be performed with pure substances (2, 23, 117) or crude extracts (73, 203, 182). The methods used for the two types of organisms are similar. The two most commonly used screens to determine antimicrobial susceptibility are the broth dilution assay (18, 89, 219) and the disc or agar well diffusion assay (153); clinical microbiologists are very familiar with these assays. Adaptations such as the agar overlay method (138) may also be used. In some cases, the inoculated plates or tubes are exposed to UV light (221) to screen for the presence of light-sensitizing photochemicals. Other variations of these methods are also used. For instance, to test the effects of extracts on invasive Shigella species, noncytotoxic concentrations of the extracts can be added to Vero cell cultures exposed to a Shigella inoculum (235). The decrease in cytopathic effect in the presence of the plant extract is then measured.

In addition to these assays, antifungal phytochemicals can be analyzed by a spore germination assay. Samples of plant extracts or pure compounds can be added to fungal spores collected from solid cultures, placed on glass slides, and incubated at an appropriate temperature (usually 25°C) for 24 h. Slides are then fixed in lactophenol-cotton blue and observed microscopically for spore germination (179).

Of course, after initial screening of phytochemicals, more detailed studies of their antibiotic effects should be conducted. At this stage, more specific media can be used and MICs can be effectively compared to those of a wider range of currently used antibiotics. The investigation of plant extracts effective against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (190, 229) provides an example of prospecting for new compounds which may be particularly effective against infections that are currently difficult to treat. Sato et al. (190) examined the activity of three extracts from the fruiting bodies of the tree Terminalia chebula RETS against methicillin-sensitive and methicillin-resistant S. aureus as well as 12 other gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. They found that gallic acid derivatives were more effective against both types of S. aureus than they were against other species.

(ii) Viruses.

Several methods are available to detect either virucidal or inhibitory (antiviral) plant activity. Investigators can look for cytopathic effects or plaque formation (1, 111) or for transformation or proliferative effects on cell lines (48). Viral replication may be assayed by detection of viral products such as DNA, RNA, or polypeptides (127, 171). Vlietinck and Vanden Berghe (238) have noted that the method for assaying antiviral substances used in various laboratories is not standardized, and therefore the results are often not comparable to one another. These authors also point out that researchers must distinguish between merely toxic effects of agents on host cells and true antiviral properties of the plant extracts. Table 5 lists various in vitro antiviral screening assays.

TABLE 5.

In vitro antiviral screening assaysa

| Determination of viral infectivity under two conditions: I. In cultured cells during virus multiplication in the presence of a single compound (A-S) or a mixture of compounds, e.g., plant extracts (A-M). II. After extracellular incubation with a single compound (V-S) or a mixture of compounds (V-M). |

|---|

| Plaque inhibition assay (only for viruses which form plaques in suitable cell systems) |

| Titer determination of a limited number of viruses in the presence of a nontoxic dose of the test substance |

| Applicability: A-S |

| Plaque reduction assay (only for viruses which form plaques in suitable cell systems) |

| Titer determination of residual virus infectivity after extracellular action of test substance(s) (see reference for comments on cytotoxicity) |

| Applicability: V-S, V-M |

| Inhibition of virus-induced cytopathic effect (for viruses that induce cytopathic effect but do not readily form plaques in cell cultures) |

| Determination of virus-induced cytopathic effect in cell monolayers cultured in liquid medium, infected with a limited dose of virus, and treated with a nontoxic dose of the test substance(s) |

| Applicability: A-S, A-M |

| Virus yield reduction assay |

| Determination of the virus yield in tissues cultures infected with a given amount of virus and treated with a nontoxic dose of the test substance(s) |

| Virus titer determination carried out after virus multiplication by the plaque test or the 50% tissue culture infective dose end-point test |

| Applicability: A-S, A-M |

| End-point titer determination technique |

| Determination of virus titer reduction in the presence of twofold dilutions of test compound(s) |

| This method especially designed for the antiviral screening of crude extracts (238) |

| Applicability: A-S, A-M |

| Assays based on measurement of specialized functions and viral products (for viruses that do not induce cytopathic effects or form plaques in cell cultures) |

| Determination of virus specific parameters, e.g., hemagglutination and hemadsorption tests (myxoviruses), inhibition of cell transformation (Epstein-Barr virus), immunological tests detecting antiviral antigens in cell cultures (Epstein-Barr virus, HIV, HSV, cytomegalovirus) |

| Applicability: A-S, A-M, V-S, V-M |

| Reduction or inhibition of the synthesis of virus specific polypeptides in infected cell cultures, e.g., viral nucleic acids, determination of the uptake of radioactive isotope-labelled precursors or viral genome copy numbers |

| Applicability: A-S, A-M, V-S, V-M |

Reprinted from reference 238 with permission of the publisher.

It should be mentioned here that antiviral assays often screen for active substances which prevent adsorption of the microorganism to host cells; this activity is overlooked in screening procedures for antibacterial and antifungal substances. However, the large body of literature accumulating on antiadhesive approaches to bacterial infections (109) suggests that phytochemicals should be assessed for this class of action in addition to their killing and inhibitory activities.

(iii) Protozoa and helminths.

Screening plant extracts for activity against protozoa and helminths can be more complicated than screening for activity against bacteria, fungi, or viruses. Growing the organisms is often more difficult, and fewer organisms are obtained. Assays are generally specific for the microorganism. For instance, Freiburghaus et al. (73) used two methods to assay compounds for effectiveness against Trypanosoma brucei. First, 66-h tissue cultures of the trypanosomes were exposed to various concentrations of extracts, and then the MICs were determined with an inverted microscope. (In this case, the MIC was defined as the lowest concentration of extract which completely inhibited the growth of the trypanosomes.) Second, these authors used a fluorescence assay of trypanosome viability in microtiter wells.

There is great interest in plant chemicals which may have anti-infective properties for Plasmodium species. One method for testing extracts which may be toxic to plasmodia uses radiolabelled microorganisms in an erythrocyte infection assay with microtiter dishes (72). Parasitized erythrocytes are incubated with and without test substances, and the numbers of Plasmodium organisms after the incubation period are quantitated. Another laboratory directly measures decreases in the growth of Plasmodium under the influence of the extracts (29).

In vivo testing of phytochemicals.

Two prime examples of animal studies from the recent literature are the descriptions of the effects of oolong tea polyphenols on dental caries in rats (186) and cholera in mice (226) (discussed above). Another bacterial infection model, P. aeruginosa lung infection of athymic rats, was used to test subcutaneous administrations of ginseng. Treated rats had decreased lung pathology and bacterial load, although enhanced humoral immunity was thought to be at least partially responsible (207).

Perhaps because of the long-standing interest in alternative pharmaceuticals for use in developing and tropical regions of the world, many of the in vivo studies to date have examined the antiprotozoal effectiveness of plant extracts (55). Two recent studies with rats used experimental Entamoeba infections to test the effectiveness of a crude Indian herbal extract (205) and of an ethanolic extract of Piper longum fruits, probably containing the alkaloid piperine (78). After applying the chloroform extract of the legume Milletia thonningii topically to the skin of mice, Perrett et al. (175) found that it prevented the establishment of subsequent Schistosoma mansoni infection. There are also animal studies of the activity of various extracts of the bark of Pteleopsis suberosa against ulcers (53), of papaya latex against infections with the helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrus (191), and of Santolina chamaecyparissus essential oil against candidal infections (213).

An Ayurvedic formulation, Cauvery 100, was administered orally to rats either before or after diarrhea was induced by castor oil. While this trial did not test antimicrobial activities of the preparation but, rather, its effect on gut motility and ion loss in the sick animals, it showed that Cauvery 100 had both a protective and a curative effect in rats (134). A similar study with similar results was performed on rats with chemically induced ulcers (133). The Ayurvedic Ashwagandha was found to prolong the survival period of BALB/c mice infected with Aspergillus, an effect believed to be mediated by increased macrophage function (54).

Clinical trials in humans.

Of course, plants have been used for centuries to treat infections and other illnesses in humans in aboriginal groups, but controlled clinical studies are scarce. In some cases, traditional healers working together with trained scientists have begun keeping records of the safety and effectiveness of phytochemical treatments, but these are generally uncontrolled and unrandomized studies. Examples of peer-reviewed trials of the use of phytochemicals in humans are briefly reported here.

A cross-sectional epidemiological study (thus, not a randomized trial) of the effectiveness of chewing sticks versus toothbrushes in promoting oral hygiene was conducted in West Africa. The study’s authors found a reduced effectiveness in chewing-stick users compared to toothbrush users and concluded that the antimicrobial chemicals known to be present in the sticks added no oral health benefit (156). Also, regarding oral health, mouthrinses containing various antimicrobials have been evaluated in humans (reviewed in reference 240). Mouthrinses containing phytochemicals were not found to be as effective in decreasing plaque or clinical gingivitis as were Listerine or chlorhexidine.

To date, few randomized clinical trials of plant antimicrobials have been performed. Giron et al. (79) compared an extract of Solanum nigrescens with nystatin, both given as intravaginal suppositories, in women with confirmed C. albicans vaginitis. The extract proved to be as efficacious as nystatin. In 1996 the long-recognized effects of cranberry juice on urinary tract infections were studied in a group of elderly women. No data are provided by the author about clinical outcomes, but treated women had fewer bacteria in their urine than did the untreated group (17).

Four different Ayurvedic formulations were tested against a placebo for their effectiveness against acne vulgaris. One of the formulations, Sunder Vati, produced a significantly greater reduction in lesion count than did the other three and the placebo. No toxic side effects were observed (170). Two proprietary compounds derived from tropical plants, Provir, for the treatment of respiratory viral infections, and Virend, a topical antiherpes agent, were tested in clinical trials in 1994 (114). Since then, the efficacy and safety of Virend have been established in phase II studies (167).

PLANTS WITH EFFICACY AGAINST HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS

Effective therapies for HIV infection are being sought far and wide, in the natural world as well as in laboratories. As one example of in vivo anti-HIV studies, infection in mice has been studied. Glycyrrhizin, found in Glycyrrhiza plants (the source of licorice), extended the life of the retrovirus-infected mice from 14 to 17 weeks (242). A crude extract of the cactus Opuntia streptacantha had marked antiviral effects in vitro, and toxicity studies performed in mice, horses, and humans found the extract to be safe (3).

The scope of studies of anti-HIV plant extracts is too broad to handle in detail in the present review, but Table 6 summarizes many of the compounds studied to date as well as their purported targets of action. The interested reader is referred to several useful reviews (36, 155, 172, 217).

TABLE 6.

Compounds with anti-HIV activity

| Target | Compound | Class | Plant | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reverse transcriptase | Ellagitannin | Tannin | —a | 155 |

| Hydroxymaprounic acid, hydroxybenzoate | Terpenoids | Maprounea africana | 173 | |

| Betulinic acid, platanic acid | Terpenoids | Syzigium claviflorum | 74 | |

| Catechin | Polyphenol | — | 147 | |

| Faicalein, quercetin, myricetin, baicalin | Flavonoids | Quercus rubra, others | 165, 208, 216 | |

| Nigranoic acid | Terpenoids | Schisandra sphaerandra | 212 | |

| Amentoflavone, scutellarein, others | Flavonoids, flavones | — | 96, 146, 164, 165, 208, 217, 218 | |

| Benzophenanthridine | Alkaloid | — | 200, 217 | |

| Protoberberine | Alkaloid | — | 217 | |

| Psychotrines | Alkaloids | Ipecac (Cephaelis ipecacuanha) | 217 | |

| Michellamine B | Alkaloid | Ancistrocladus korupensis | 142 | |

| Suksdorfin | Coumarins | Lomatium suksdorfii | 126 | |

| Coriandrin | Coumarin | Coriander (Coriandrum sativum) | 99 | |

| Caffeic acid | Tannin | Hyssop officinalis | 119 | |

| Cornusin, others | Condensed and hydrolyzable tannins | Cornus officinalis and others | 111 | |

| Swertifrancheside | Flavonoid | Swertia franchetiana | 172 | |

| Salaspermic acid | Flavonoid | Trypterygium wilfordii | 40 | |

| Glycyrrhizin | Flavonoid | Licorice (Glycyrrhiza rhiza) | 102, 242 | |

| — | Protein | Cactus (Opuntia streptacantha) | 3 | |

| Methyl nordihydroguaiaretic acid | Lignan | Many trees | 80 | |

| Thuja polysaccharide | Polysaccharide | Thuja occidentalis | 160 | |

| Lignin-polysaccharide complexes | Japanese white pine (Pinus parvifloria) | 126 | ||

| Integrase | — | Flavonoids, flavones | — | 32, 67 |

| MAP30, GAP31, DAP 32, DAP 30 | Proteins | Momordica charantia, Gelonium multiflorum | 97, 128–130 | |

| — | Lectins | — | 20 | |

| Caffeic acid | Terpenoid | — | 68 | |

| Curcumin | Terpenoid | Turmeric (Curcuma longa) | 139 | |

| Quercetin | Flavonoid | Quercus rubra | 67 | |

| Protease | Carnosolic acid | Terpenoid | Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) | 171 |

| Ursolic acid | Terpenoids | Geum japonicum | 246 | |

| Flavonoids, flavones | 32, 48, 67 | |||

| Adsorption | Mannose-specific lectins | Lectins | Snowdrop (Galanthus), daffodil (Narcissus), amaryllis (Amaryllis), Gerardia | 148 |

| Schumannificine 1 | Alkaloid | Schumanniophyton magnificum | 94 | |

| Prunellin | Polysaccharide | Prunella | 249 | |

| Viral fusion | Mannose- and N-acetylglucosamine-specific lectins | Lectins | Cymbidium hybrid, Epiactic helleborine, Listeria ovata, Urtica dioica | 20 |

| Syncytium formation | Propolis | Mixture | Various trees | 9, 52 |

| Michellamine B | Alkaloid | Ancistrocladus korupensis | 142 | |

| MAR-10 | Polysaccharide | Hyssop officinalis | 81 | |

| Interference with cellular factors | Chrysin | Flavone | Chrysanthemum morifolium | 48 |

| 29,000-mol-wt protein | Protein | Pokeweed (Phytolacca) | 41 | |

| Hypericin | Anthraquinone | St. John’s wort (Hypericum) | 41, 99 | |

| Camptothecin | Alkaloid | ? | 169 | |

| Trichosanthin, momorcharins | Ribosome-inactiving proteins | Cucurbitaceae family | 141 | |

| Unknown | — | Sulfated polysaccharide | Prunella vulgaris | 214 |

| — | Sulfonated polysaccharide | Viola yedoensis | 154 | |

| Jacalin | Lectin | ? | 46, 64 | |

| Zingibroside R-1 | Terpenoid | Panax zingiberensis Wu et Feng | 86 | |

| Thiarubrines | Terpenoids | Asteraceae | 98 | |

| Chrysin | Flavonoid | Chrysanthemum morifolium | 96 | |

| — | Essential oil/terpenoids | Houttuynia cordata | 88 |

—, unspecified.

COMMERCIAL AVAILABILITY AND SAFETY OF COMPOUNDS

A wide variety of plant extracts, mixtures, and single plant compounds are available in the United States without a prescription through health food stores and vitamin retailers. For example, preparations of flavones (brand names Flavons 500 and Citrus Bioflavonoids) are sold by supplement suppliers. Capsaicin appears in a topical antiarthritis cream available in mainstream grocery and drug stores. The over-the-counter preparations are relatively unregulated. This results in preparations of uncertain and variable purity.

Many stores also sell whole dried plants, which have been found occasionally to be misidentified, with potentially disastrous consequences. Obviously, many plants can also be grown by the consumer in home gardens. In 1994, Congress passed the Dietary Supplement Health Education Act, which required the Food and Drug Administration to develop labeling requirements specifically designed for products containing ingredients such as vitamins, minerals, and herbs intended to supplement the diet. The new rules, issued in late 1997, require products to be labeled as a dietary supplement and carry a “Supplement Facts” panel with information similar to the “Nutrition Facts” panels appearing on processed foods. The rules also require that products containing botanical ingredients specify the part of the plant used (71).

The Food and Drug Administration regulates dietary supplements as foods, as long as no drug claims are made for them (63). Other organizations overseeing herbals and botanicals are the American Dietetic Association’s Commission on Dietary Supplement Labels (11) and the Food and Nutrition Science Alliance (12).

The first investigational new drug application for herbal pharmaceuticals, available by prescription, was submitted in 1997 (13). Whether this is the beginning of a substantial “rush to market” is unclear. Some analysts suggest that pharmaceutical companies will not invest in drug testing for botanicals since it is still unclear whether proprietary claims can be made (49). Richard van den Broek, industry analyst, concurs, saying that most novel antibiotic research is being conducted instead by biotechnology companies (7).

Plants and/or plant components which are currently available to consumers as supplements through commercial outlets are among those listed in Table 1. Rough toxicity rankings are also provided. It has long been recognized that possibly therapeutic foodstuffs may also contain substances which act as poisons in humans (132). Clinical scientists and practitioners are best advised to be aware of the widespread self-medication with these products and to consider their effects on patients.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Scientists from divergent fields are investigating plants anew with an eye to their antimicrobial usefulness. A sense of urgency accompanies the search as the pace of species extinction continues. Laboratories of the world have found literally thousands of phytochemicals which have inhibitory effects on all types of microorganisms in vitro. More of these compounds should be subjected to animal and human studies to determine their effectiveness in whole-organism systems, including in particular toxicity studies as well as an examination of their effects on beneficial normal microbiota. It would be advantageous to standardize methods of extraction and in vitro testing so that the search could be more systematic and interpretation of results would be facilitated. Also, alternative mechanisms of infection prevention and treatment should be included in initial activity screenings. Disruption of adhesion is one example of an anti-infection activity not commonly screened for currently. Attention to these issues could usher in a badly needed new era of chemotherapeutic treatment of infection by using plant-derived principles.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance of Emily A. Horst.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abou-Karam M, Shier W T. A simplified plaque reduction assay for antiviral agents from plants. Demonstration of frequent occurrence of antiviral activity in higher plants. J Nat Prod. 1990;53:340–344. doi: 10.1021/np50068a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Afolayan A J, Meyer J J M. The antimicrobial activity of 3,5,7-trihydroxyflavone isolated from the shoots of Helichrysum aureonitens. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;57:177–181. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(97)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmad A, Davies J, Randall S, Skinner G R B. Antiviral properties of extract of Opuntia streptacantha. Antiviral Res. 1996;30:75–85. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(95)00839-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed A A, Mahmoud A A, Williams H J, Scott A I, Reibenspies J H, Mabry T J. New sesquiterpene α-methylene lactones from the Egyptian plant Jasonia candicans. J Nat Prod. 1993;56:1276–1280. doi: 10.1021/np50098a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akpata E S, Akinrimisi E O. Antibacterial activity of extracts from some African chewing sticks. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1977;44:717–722. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(77)90381-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali-Shtayeh M S, Al-Nuri M A, Yaghmour R M R, Faidi Y R. Antimicrobial activity of Micromeria nervosa from the Palestinian area. J Ethnopharmacol. 1997;58:143–147. doi: 10.1016/s0378-8741(97)00088-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alper J. Effort to combat microbial resistance lags. ASM News. 1998;64:440–441. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amaral J A, Ekins A, Richards S R, Knowles R. Effect of selected monoterpenes on methane oxidation, denitrification, and aerobic metabolism by bacteria in pure culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:520–525. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.2.520-525.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amoros M, Sauvager F, Girre L, Cormier M. In vitro antiviral activity of propolis. Apidologie. 1992;23:231–240. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amoros M, Simoes C M O, Girre L. Synergistic effect of flavones and flavonols against herpes simplex virus type 1 in cell culture. Comparison with the antiviral activity of propolis. J Nat Prod. 1992;55:1732–1740. doi: 10.1021/np50090a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anonymous. Commission on Dietary Supplement Labels issues final report. J Am Diet Assoc. 1998;98:270. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(98)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anonymous. FANSA releases statement about dietary supplement labeling. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97:728–729. [Google Scholar]