Abstract

Background

With the improvement of ultrasound technology, the likelihood of detection of major fetal structural anomalies in mid‐pregnancy has increased considerably. Upon the detection of serious anomalies, women typically are offered the option of pregnancy termination. Additionally, there are still many reasons other than fetal anomalies why women seek abortion in the mid‐trimester.

Objectives

To compare different methods of second trimester medical termination of pregnancy for their efficacy and side‐effects.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE, Popline and reference lists of retrieved papers and other sources.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials (RCTs) examining medical regimens for termination of pregnancy of a singleton living fetus between 12‐28 weeks' gestation were analysed. The outcome measures were the induction to abortion interval, abortion rate within 24 hours, need for surgical evacuation, blood loss, uterine rupture, pain, and side‐effects.Trials including >20% fetal death, multiple pregnancies, previous uterine scars and regimens which involved cervical preparation were excluded.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors selected the trials and three authors extracted data.

Main results

Fourty RCTs were included, addressing various agents for pregnancy termination and methods of administration. When used alone, misoprostol was an effective inductive agent, though it appeared to be more effective in combination with mifepristone. However, the evidence from RCTs is limited.

Misoprostol was preferably administered vaginally, although among multiparous women sublingual administration appeared equally effective. A range of doses of vaginally administered misoprostol has been used. No randomised trials comparing doses of misoprostol were identified; however low doses of misoprostol appear to be associated with fewer side‐effects while moderate doses appear to be more efficient in completing abortion. Four RCTs showed that the induction to abortion interval with 3‐hourly vaginal administration of prostaglandins is shorter than 6‐hourly administration without an increase in side‐effects.

Many studies reported the need for surgical evacuation. Indications for surgical evacuation include retained products of the placenta and heavy vaginal bleeding. Fewer women required surgical evacuation when misoprostol was administrated vaginally compared with women receiving intra‐amniotical PGF2a. Mild, self‐limiting diarrhoea was more common among women who received misoprostol compared to other agents.

Authors' conclusions

Medical abortion in the second trimester using the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol appeared to have the highest efficacy and shortest abortion time interval. Where mifepristone is not available, misoprostol alone is a reasonable alternative. The optimal route for administering misoprostol is vaginally, preferably using tablets at 3‐hourly intervals. Apart from pain, the side‐effects of vaginal misoprostol are usually mild and self limiting. Conclusions from this review are limited by the gestational age ranges and variable medical regimens, including dosing, administrative routes and intervals of medication, of the included trials.

Plain language summary

Planned abortion after three months of pregnancy can be done using several medicines. This review looked at which medical procedure is the best.

There are many medical methods for planned termination of pregnancy in the second trimester of pregnancy (abortion after three months). We did a search of the scientific literature to find out which is the best method. We identified 38 studies and came to the conclusion that misoprostol is the drug of choice for medical pregnancy termination, preferably in combination with mifepristone which facilitates the effectiveness of misoprostol. Misoprostol works best when it is administered into the vagina. Women who had previously given birth could take misoprostol by mouth (under the tongue). Irrespective of the medication used for second trimester termination there is a considerable risk of surgical intervention because of vaginal bleeding or incomplete abortion.

Background

With the wide‐scale introduction of prenatal screening programmes the issue of second trimester abortion has become increasingly relevant, in particular for women whose pregnancies are complicated by a serious fetal anomaly (Asch 1999; Ballantyne 2009; Boyd 2008). Additionally, there are many reasons other than fetal anomalies for which women seek abortion in the midtrimester (Drey 2006; Grimes 1998; Ingham 2008). Second trimester abortion for fetal structural anomalies may have advantages over surgical abortion as it is operator independent and the intact fetus may be preferable for feto‐pathological examination (Akgun 2007; Isaksen 1998; Isaksen 1999; Kaasen 2006). Medical abortion, however, also has several limitations including the need for the hospitalisation, the need for surgical removal of (the retained products of) the placenta when indicated, and the emotional impact of the process of labor and delivery on women who choose to end a pregnancy.

Medical abortion in the first trimester of pregnancy is considered successful if complete expulsion of the conceptus occurs without the need for surgical intervention (Christin‐Maitre 2000). Beyond the first trimester, definitions differ but generally consider expulsion of the fetus separate from management of the placenta.

Several regimens for second trimester abortion have been published. Most of these are based on misoprostol or gemeprost, which are synthetic prostaglandin E1 analogues (PGE1), and used alone or misoprostol combined with mifepristone. Comparison of medical methods with surgical evacuation for mid‐trimester termination of pregnancy is the subject of another review (Lohr 2008).

Agents used for medical abortion

Prostaglandins

Prostaglandins and their analogues are widely used for medical termination of pregnancy. Prostaglandins are produced by almost every tissue in the body and play a major role in human reproduction and in many other vital processes. To date, nine groups (A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I) and three types (PG1, PG2, PG3) of prostaglandins have been identified. Prostaglandins of the F and E series are the most important prostaglandins involved in pregnancy, labor, delivery and puerperium. PG receptors are always present in myometrial tissue.

Misoprostol (PGE1) is increasingly used for second trimester termination of pregnancy (Friedman 2001; Goldberg 2001; Wagner 2005; Weeks 2005). Misoprostol is marketed for use in the prevention and treatment of peptic ulcer disease, and it is registered for obstetric indications, including abortion, in a few countries. It is inexpensive, stable at room temperature and it is rapidly absorbed by vaginal, sublingual, buccal and oral routes (Tang 2002; Zieman 1997). Moreover, misoprostol is reportedly associated with few, relatively minor side‐effects. Serious complications such as uterine rupture are rare.

Gemeprost (PGE1) is formulated as a vaginal suppository which requires refrigeration, and is not as widely available as misoprostol. Like other prostaglandins, it induces uterine contractions and cervical softening.

Dinoprost (PGF2α) and dinoprostone (PGE2) are natural prostaglandins which induce uterine activity and are available for intravenous, intra‐amniotic and extra‐amniotic use.

Carboprost (15 methyl PGF2α) can be given by intramuscular or intra‐amniotic injection and its methyl ester can be given as vaginal suppository. Carboprost and its methyl ester are both effective in inducing uterine contractions.

Sulprostone (PGE2) is used intravenously. The intramuscular preparation of sulprostone is no longer available because it was associated with cardiovascular complications, such as acute myocardial infarction and hypotension (Ulmann 1992).

Uterotonic agents other than prostaglandins

Mifepristone, also known as RU 486 or RU 38486, is a 19‐norsteroid that specifically blocks the receptors for progesterone and glucosteroids. It is used as pretreatment 24 to 48 hours prior to the induction of first trimester abortion with a prostaglandin analogue. It sensitizes the myometrium of the uterus to prostaglandin (Belanger 1981; Bygdeman 1985; Norman 1992; Swahn 1988).

Oxytocin is released physiologically by the posterior pituitary and stimulates uterine contractions. The sensitivity of the uterus to oxytocin increases with gestational age.

Injection techniques

Intra‐amniotic instillation

Several chemical solutions for intra‐amniotic injection techniques have been used, including formalin, glucose, hypertonic saline, urea and PGF2α. When using hypertonic saline, a spinal needle is passed through the abdominal wall into the amniotic cavity. A variable amount of the amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus is removed and replaced by 150 to 250 ml of 20% saline chloride solution that will induce abortion (Bygdeman and Gemzell‐Danielsson 2008).

Extra‐amniotic instillation

Instead of passing a spinal needle directly into the amniotic sac, effective irritants, such as ethacridine lactate or PGF2α, can be introduced through the cervix into the extra‐amniotic space, that is, the space between the uterine wall and the fetal membranes. Ethacridine lactate is an organic compound based on acridine. Its primary use is as an antiseptic in solutions of 0.1%. When used as an agent for second trimester abortion, it is thought to stimulate endogenous prostaglandin production and subsequent uterine contractions. Up to 150 ml of 0.1% ethacridine is instilled into the extra‐amniotic space using a Foley catheter. Oxytocin intravenous administration is often used concomitantly to expedite fetal expulsion (Bygdeman and Gemzell‐Danielsson 2008).

Description of the problem or issue

Second trimester abortions constitute 10% to 15% of all induced abortions worldwide but are responsible for two‐thirds of major abortion‐related complications (Drey 2006; Grimes 1998). Medical methods for second trimester induced abortion have improved considerably during the last decades in terms of efficacy and safety; however, a variety of regimens remain in use.

Why it is important to do this review

Because of improved ultrasound technology, the prenatal detection of fetal structural anomalies during the second trimester of pregnancy has improved substantially. For this reason, the demand for medical methods to terminate pregnancy during the second trimester has also increased (Grimes 1998). Additionally, there are a number of other reasons why women seek abortion in the mid‐trimester. There are many medical regimens for mid‐trimester termination of pregnancy. This review aims to identify the most effective medical regimens for mid‐trimester abortion with the fewest side‐effects.

Objectives

To evaluate the medical regimens for second trimester medical abortion in terms of efficacy and side‐effects.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials were considered for inclusion if different medical methods, routes of application or doses used for second trimester medical abortion were compared.

Types of participants

Studies which included healthy women undergoing a second trimester abortion were eligible if carrying a singleton, living fetus between 12 to 28 weeks gestation. Studies including women with multiple pregnancies, or those who had cervical preparation prior to the abortion procedure were excluded.

Types of interventions

Different medical methods, administration routes or doses of medication used for second trimester medical abortion.

Types of outcome measures

The main outcome measures were the induction to abortion interval and the number of complete abortions within 24 hours. The primary endpoint for the abortion interval is expulsion of the fetus. The secondary endpoint for the abortion interval is the expulsion of the placenta. In addition, other secondary outcome measures included the need for surgical evacuation (non‐emergency procedure, emergency procedure, or not specified, including manual removal of the placenta), blood loss (measured, need for blood transfusion or clinically relevant drop in haemoglobin), uterine rupture, pain resulting from the procedure (reported by the women or measured by use of analgesics), nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. The table Characteristics of included studies includes whether a surgical intervention was performed routinely in the study.

Potential confounding

The sensitivity of the myometrium for uterotonic drugs increases with gestational age. Hence, the longer the gestation, the less uterotonic drugs are needed. Apart from gestational age, parity could also be viewed as a potential confounder as multiparous women appear to have a shorter time interval to abortion. Differential treatment effects could theoretically be ascribed by differences in gestational age or parity. Parity and gestational age of study participants are listed under Characteristics of included studies.

Search methods for identification of studies

See:Collaborative Review Group search strategy.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library), MEDLINE and Popline were systematically searched. Reference lists of retrieved papers were searched. Electronic literature search was conducted using the following key words: (induced abortion) AND (second trimester) AND (mifepristone OR misoprostol OR methotrexate OR dinoprost OR dinoprostone OR carboprost OR sulprostone OR gemeprost OR meteneprost OR epostane OR oxytocin OR RU 486 OR mifegyne) OR ethacridine lactate AND ((randomised controlled trial[pt] OR controlled clinical trial[pt] OR randomized controlled trials [mh] OR random allocation [mh] OR double‐blind method [mh] OR single‐blind method [mh] OR clinical trial [pt] OR clinical trials [mh] OR ("clinical trial" [tw] ) OR ((singl* [tw] OR doubl* [tw] OR tripl* [tw] ) AND (mask* [tw] OR blind* [tw] )) OR ("latin square" [tw] ) OR placebos [mh] OR placebo* [tw] OR random* [tw] OR research design [mh:noexp] OR comparative study [mh] OR evaluation studies [mh] OR follow‐up studies [mh] OR prospective studies [mh] OR cross‐over studies [mh] OR control* [tw] OR prospectiv* [tw] OR volunteer* [tw] ) NOT (animal [mh] NOT human [mh]) )

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

The selection of trials for inclusion was performed independently by two review authors after employing the research strategy described previously. Trials under consideration were evaluated for inclusion and methodological quality without consideration of the results. This review is limited to randomised controlled trials, thereby focusing on four types of medical interventions for second trimester termination of pregnancy, that is (1) mifepristone and prostaglandin, (2) misoprostol, (3) other prostaglandins and (4) hyperosmolar agents (hypertonic saline, ethacridine lactate).

A form was designed to facilitate the process of data extraction which was performed by two of the reviewers independently. There were no discrepancies between the reviewers in either decision of inclusion/exclusion of studies or in data extraction.

Trials were not excluded based on an arbitrary cut‐off limit regarding losses to follow up. Subgroup analyses were planned for early and late second trimester abortions as the performance of methods may differ with gestational age.

Trials describing the use of quinine were excluded. Trials including more than 20% fetal death at the onset of treatment (unless separate analysis was available), multiple pregnancies, women with uterine scars (if reportedly included in the trial) and regimens which included cervical preparation prior to the abortion procedure were excluded.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted by two authors from eligible studies. Study characteristics (type of study, allocation, blinding), participants characteristics (number, gestational age), interventions, main outcome measures and results were recorded. An attempt was made to obtain additional information from authors if required.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The quality of studies was assessed without blinding to authorship or journal. Bias was assessed using the following.

1. Allocation concealment. The quality score for concealment of allocation was assigned to each trial using the criteria in the Cochrane Handbook:

A adequate concealment of allocation;

B unclear whether adequate concealment of allocation;

C inadequate concealment of allocation (includes quasi‐randomised studies.

Only trials scoring A or B were included in the review.

2. Blinding of participants, clinicians and investigators.

3. Protection against exclusion bias.

4. Appropriate analysis of data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was analysed using the I² statistic (Higgins 2003). I² values of 25%, 50%, and 75% correspond to low, medium and high levels of heterogeneity.

Data synthesis

Data analyses was performed by using Revman 5 software.

Trials that were conducted within the subject of this review included the comparison of different medical methods, application methods and dose regimens. For this reason, the trials were considered by medical regimen comparing the outcome measures for each regimen as described earlier. The different comparisons are as follows.

Comparison 1: mifepristone + misoprostol versus mifepristone + gemeprost.

Comparison 2: mifepristone + misoprostol versus misoprostol alone.

Comparisons 3 to 5: routes of administration of misoprostol combined with mifepristone:

Comparison 3: vaginal use versus the oral use of misoprostol;

Comparison 4: vaginal use versus the sublingual use of misoprostol;

Comparison 5: oral use versus the sublingual use of misoprostol.

Comparison 6: dosing interval of misoprostol following mifepristone.

Comparison 7: dosing of mifepristone previous to misoprostol.

Comparison 8: combined regimen of mifepristone + gemeprost.

Comparisons 9 to 11: misoprostol versus another prostaglandin:

Comparison 9: misoprostol versus intra‐amniotic PGF2α;

Comparison 10: misoprostol versus gemeprost;

Comparison 11: misoprostol versus dinoprostone.

Comparisons 12 to 13: routes of administration of misoprostol:

Comparison 12: vaginal use versus the oral use of misoprostol;

Comparison 13: vaginal use versus the sublingual use of misoprostol.

Comparison 14: misoprostol tablet insertion versus gel insertion.

Comparisons 15 to 16: time interval for repeat dosing of misoprostol or gemeprost:

Comparison 15: Time interval of misoprostol;

Comparison 16: Time interval of gemeprost.

Comparison 17: low dose versus a higher dose of misoprostol.

Comparisons 18 to 19: prostaglandin E2 versus prostaglandin F2α:

Comparison 18: prostaglandin E2 versus prostaglandin F2α;

Comparison 19: prostaglandin E2 versus prostaglandin F2α + oxytocin.

Comparison 20: intra‐amniotic instillation of prostaglandin F2α versus intra‐amniotic instillation of hypertonic saline (20%).

Comparison 21: combined regimen intra‐amniotic prostaglandin F2α + hypertonic saline.

Comparison 22: prostaglandin E1 vaginally versus the intra‐amniotic instillation of prostaglandin F2α + hypertonic saline.

Comparison 23: prostaglandins versus ethacridine lactate.

Comparison 24: ethacridine lactate versus normal saline.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies;Characteristics of excluded studies

Results of the search

Eighty‐eight studies underwent full review. Full text review excluded 52 studies as they were not randomised; used inadequate concealment (score C); included over 20% fetal demise, multiple pregnancies, patients with uterine scarring; a pre‐treatment trial, including medical or mechanical dilatation of the cervix. See Characteristics of excluded studies.

Forty studies were included in this review. Due to the diversity of the interventions, the review concerns the comparison of 24 regimens. Three trials compared more than two different groups and the interventions are therefore listed as different comparisons (Mehta 1975 a; Mehta 1975 b; Muzsnai 1979 a; Muzsnai 1979 b; Muzsnai 1979 c; Muzsnai 1979 d; Nuutila 1997 a; Nuutila 1997 b; Nuutila 1997 c). The main outcomes considered were induction to abortion interval or completed abortion within 24 hours.

Included studies

Four studies (Borgida 1995; Ho 1996; Nielsen 1975; Steyn 1993) each enrolled 50 patients or less.

Four separate interventions were used.

1. Mifepristone and prostaglandin

Three studies (210 patients) compared a regimen of mifepristone and misoprostol to mifepristone and gemeprost (Bartley 2002; el‐Refaey 1993; Ho 1996).

One study (64 patients) compared mifepristone to a placebo prior to misoprostol induced abortion (Kapp 2007).

-

Five studies (500 patients) compared different routes of administration of misoprostol combined with mifepristone:

vaginal use compared to oral use (306 patients) (El‐Refaey 1995; Ho 1997; Ngai 2000);

vaginal use compared to sublingual use (76 patients) (Hamoda 2005);

oral use compared to sublingual use (118 patients) (Tang 2005).

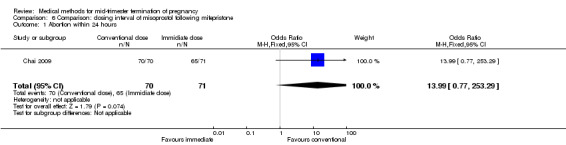

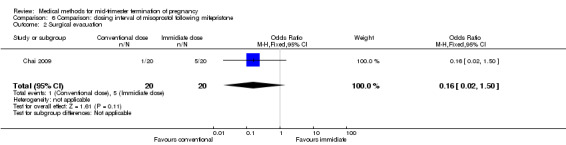

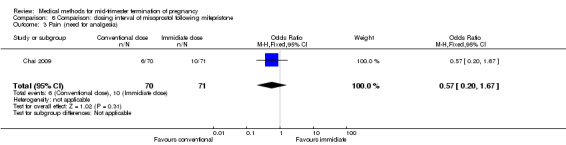

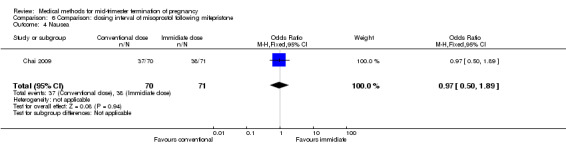

One study (141 patients) compared the dosing interval of misoprostol following mifepristone administration (Chai 2009).

One study (70 patients) compared the dosage of mifepristone before misoprostol was administered (Webster 1996).

One study (100 patients) compared 0.5mg and 1.0 mg gemeprost combined with mifepristone (Thong 1996).

2. Misoprostol

-

Five studies (693 patients) compared misoprostol to another prostaglandin:

one studies (125 patients) compared the vaginal use of misoprostol to PGF2α (Su 2005);

two studies (221 patients) compared the vaginal use of misoprostol to gemeprost (Nuutila 1997 a; Nuutila 1997 b; Wong 1998);

one study (130 patients) compared the vaginal use of misoprostol to dinoprostone (Makhlouf 2003).

-

Five studies (812 patients) compared different routes of administration of misoprostol:

vaginal use compared to oral use (310 patients) (Akoury 2004; Bebbington 2002; Behrashi 2008);

vaginal use compared to sublingual use (502 patients) (Bhattacharjee 2008; Tang 2004; von Hertzen 2009).

One study (148 patients) compared misoprostol tablets to gel insertion (Pongsatha 2008).

Three studies (427 patients) compared different time intervals of misoprostol or gemeprost (Armatage 1996; Herabutya 2005; Wong 2000).

Two studies (133 patients) compared different doses of misoprostol (Nuutila 1997 c; Ozerkan 2009).

2. Other prostaglandins

Three studies (143 patients) compared prostaglandin E2 to prostaglandin F2α (Borgida 1995; Sorensen 1984; Steyn 1993).

3. Hyperosmolar agents

Four studies (1670 patients) compared hypertonic saline and prostaglandin F2α (Faktor 1988; Mehta 1975 a; Mehta 1975 b; Nielsen 1975; WHO 1976).

One study (385 patients) compared different regimens of prostaglandin F2α and hypertonic saline (Muzsnai 1979 a; Muzsnai 1979 b; Muzsnai 1979 c; Muzsnai 1979 d).

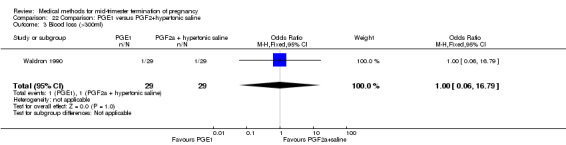

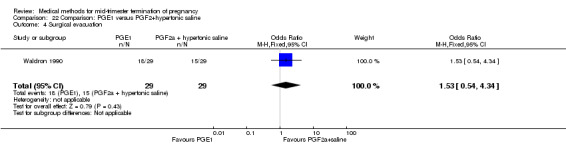

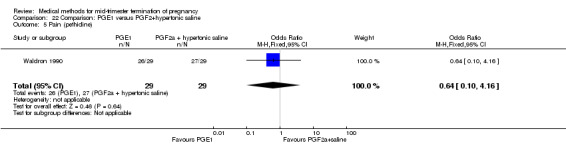

One study (58 patients) compared gemeprost to prostaglandin F2α and hypertonic saline (Waldron 1990).

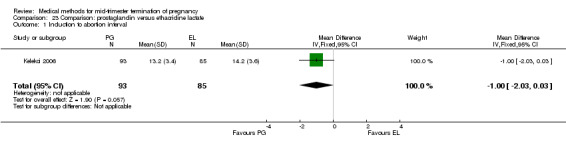

Three studies (302 patients) compared prostaglandins to ethacridine lactate (Inan 1997; Kelekci 2006; Olund 1978).

One study (37 patients) compared ethacridine lactate to normal saline (Zauva 1989).

Risk of bias in included studies

Only randomised controlled trials were included in this review. Thirty‐two studies reported the method of randomisation (Akoury 2004; Armatage 1996; Bartley 2002; Bebbington 2002; Bhattacharjee 2008; Borgida 1995; Chai 2009; el‐Refaey 1993; El‐refaey 1995; Hamoda 2005; Herabutya 2005; Ho 1996; Ho 1997; Kapp 2007; Kelekci 2006; Makhlouf 2003; Mehta 1975 a; Mehta 1975 b; Ngai 2000; Nuutila 1997 a; Nuutila 1997 b; Nuutila 1997 c; Ozerkan 2009; Pongsatha 2008; Sorensen 1984; Steyn 1993; Su 2005; Tang 2004; Tang 2005; Thong 1996; von Hertzen 2009; Webster 1996; WHO 1976; Wong 1998; Wong 2000). For more detailed information, see the section Included studies. Eleven studies did not state the inclusion or exclusion criteria (Bartley 2002; el‐Refaey 1993; El‐refaey 1995; Faktor 1988; Inan 1997; Mehta 1975 a; Mehta 1975 b; Nielsen 1975; Nuutila 1997 a; Nuutila 1997 b; Nuutila 1997 c; Olund 1978; Ozerkan 2009; Webster 1996).

Allocation

Allocation concealment was adequately reported in 28 studies (Akoury 2004; Armatage 1996; Bartley 2002; Bebbington 2002; Bhattacharjee 2008; Borgida 1995; Chai 2009; el‐Refaey 1993; El‐refaey 1995; Hamoda 2005; Herabutya 2005; Ho 1996; Ho 1997; Kapp 2007; Makhlouf 2003; Mehta 1975 a; Mehta 1975 b; Ngai 2000; Nuutila 1997 a; Nuutila 1997 b; Nuutila 1997 c; Steyn 1993; Su 2005; Tang 2004; Tang 2005; Thong 1996; von Hertzen 2009; Webster 1996; WHO 1976; Wong 1998; Wong 2000).

Blinding

Blinding (no further explanation was given) was reported in one study (von Hertzen 2009). Blinding of participants was reported in one study (Ngai 2000). Blinding of participants and clinicians was reported in two studies (Ho 1997; Tang 2005). Blinding of participants, clinicians and researchers was reported in one study (Kapp 2007).

Effects of interventions

For outcomes using a continuous scale, the mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were used to asses the effects of the intervention. For dichotomous outcomes the results were expressed using odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

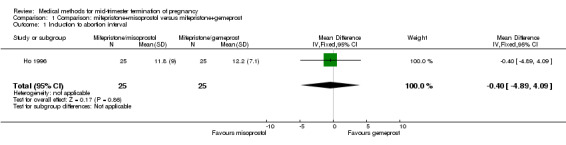

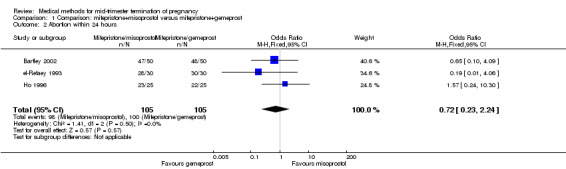

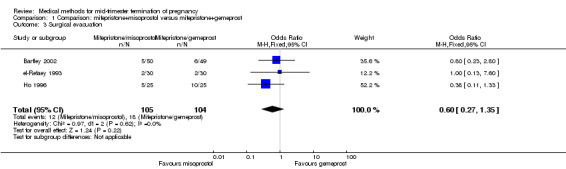

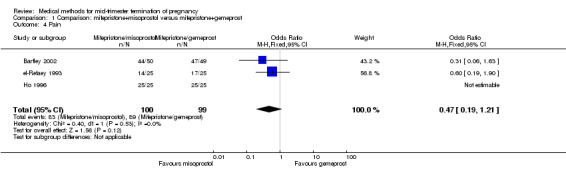

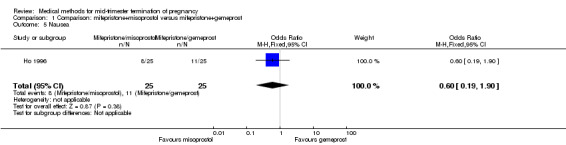

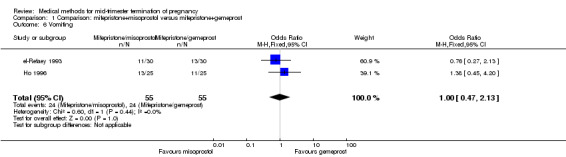

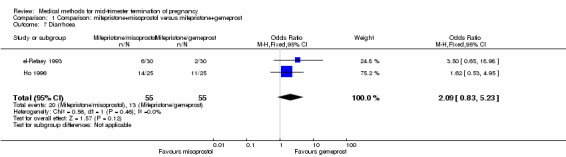

Comparison 1: combined regimen mifepristone + misoprostol versus mifepristone + gemeprost

Three trials (Bartley 2002; el‐Refaey 1993; Ho 1996) were included in this comparison. In total, 210 women were eligible for analysis. In regards to the induction to abortion interval, el‐Refaey 1993 did not provide standard deviations, and thus precluded inclusion of these data in the meta‐analysis. The median induction to abortion interval was 8 hrs (range 1 to 60) and 9.1 hrs (range 3 to 22) for the oral use of 400 μg misoprostol and the 1 mg gemeprost pessaries group respectively (not significant). There were no significant differences in the induction‐to‐abortion interval (Analysis 1.1), abortion rate within 24 hours (Analysis 1.2), need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 1.3) or side‐effects (pain, Analysis 1.4; nausea, Analysis 1.5; vomiting, Analysis 1.6; diarrhoea, Analysis 1.7) between regimens using mifepristone with either misoprostol or gemeprost.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus mifepristone+gemeprost, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus mifepristone+gemeprost, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24 hours.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus mifepristone+gemeprost, Outcome 3 Surgical evacuation.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus mifepristone+gemeprost, Outcome 4 Pain.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus mifepristone+gemeprost, Outcome 5 Nausea.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus mifepristone+gemeprost, Outcome 6 Vomiting.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus mifepristone+gemeprost, Outcome 7 Diarrhoea.

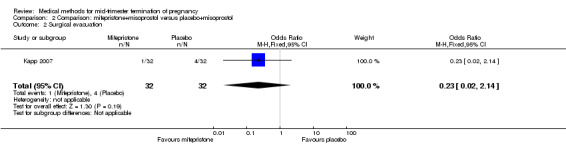

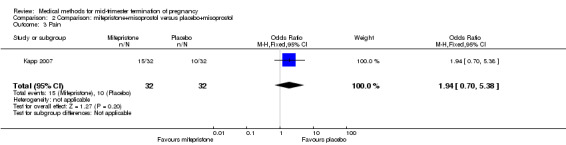

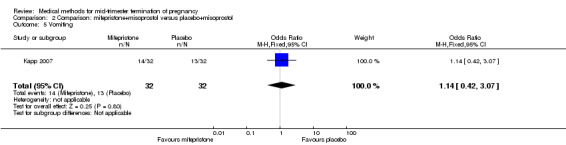

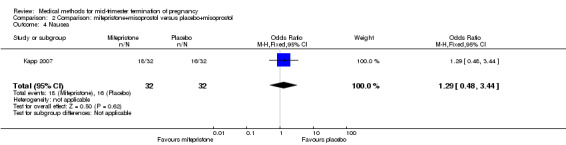

Comparison 2: misoprostol versus mifepristone + misoprostol

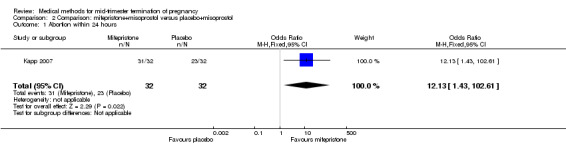

One trial (Kapp 2007) was included in this comparison. In this regimen, 64 women were eligible for analysis. Women who received mifepristone + misoprostol aborted more rapidly than women who had misoprostol alone (Analysis 2.1) (MD 12.13, 95% CI 1.43 to 102.61). No difference was found in terms of the need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 2.2), pain (Analysis 2.3), vomiting (Analysis 2.5) or nausea (Analysis 2.4).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus placebo+misoprostol, Outcome 1 Abortion within 24 hours.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus placebo+misoprostol, Outcome 2 Surgical evacuation.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus placebo+misoprostol, Outcome 3 Pain.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus placebo+misoprostol, Outcome 5 Vomiting.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus placebo+misoprostol, Outcome 4 Nausea.

Comparisons 3 to 5: routes of administration of misoprostol combined with mifepristone

In this comparison, five trials with three comparisons (El‐refaey 1995; Hamoda 2005; Ho 1997; Ngai 2000; Tang 2005) were included.

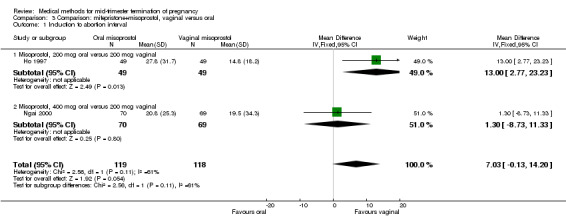

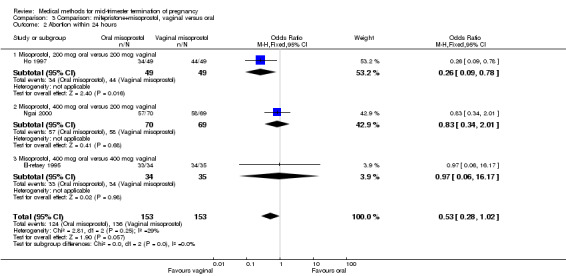

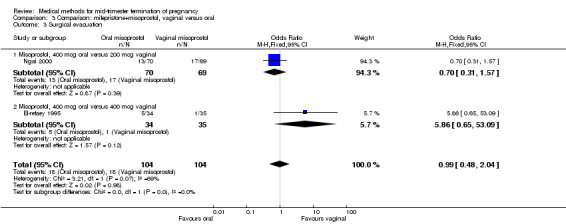

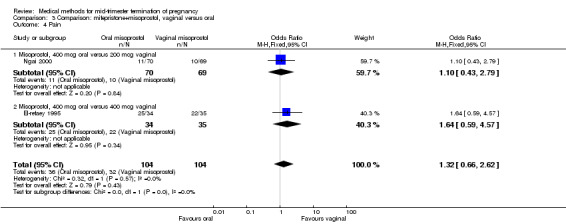

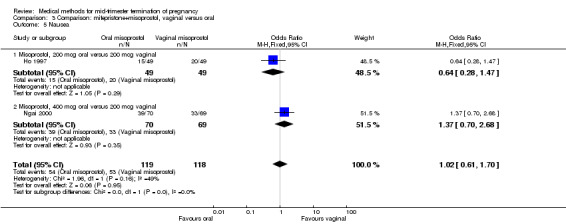

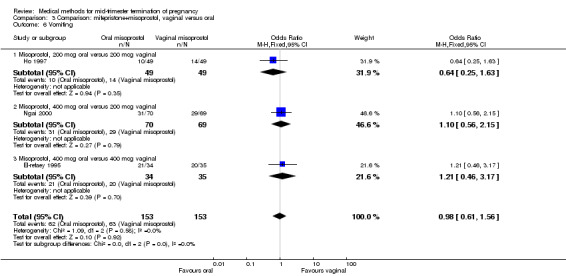

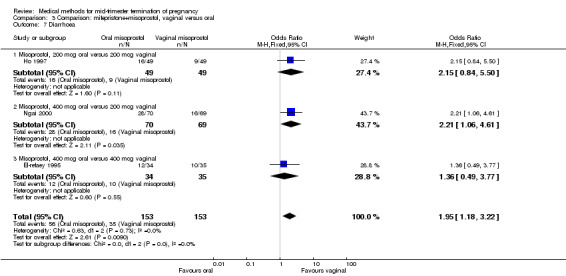

Comparison 3: vaginal use compared to oral use of misoprostol

In this comparison, three trials (El‐refaey 1995; Ho 1997; Ngai 2000) were included. In total, 306 women were eligible for analysis. The largest trial in this analysis was conducted by Ngai, comparing the oral use of 400 μg and the vaginal use of 200 μg of misoprostol, both combined with 200 mg mifepristone administered orally 36 to 48 hours in advance. In addition to this comparison, both groups received either vaginal or oral placebo tablets. Ho 1997 conducted a randomised controlled trial comparing the use of 200 μg of misoprostol orally combined with a vaginal placebo to the vaginal use of 200 μg misoprostol combined with an oral placebo, each arm combined with 200 mg mifepristone. The vaginal use of 200 μg misoprostol was superior (MD 13.00, 95% CI 2.77 to 23.23) to the oral use of 200 μg misoprostol (Analysis 3.1). When both oral and vaginal misoprostol was administered in a low dose (200 μg), the vaginal use was superior to the oral use regarding the abortion rate within 24 hours (Analysis 3.2) (OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.78). In regards to the induction‐to‐abortion interval, El Refaey 1995 did not provide a standard deviation in addition to estimates which precluded the inclusion of these data in the meta‐analysis. The mean induction to abortion interval was 6.0 hrs (95% CI 5.0 to 7.2) and 6.7 hrs (95% CI 5.8 to 7.6) for the oral and the vaginal groups respectively (not significant). No significant difference was found between the oral and vaginal use of misoprostol in terms of induction‐to‐abortion interval. In addition, no difference was found between the need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 3.3), amount of pain (Analysis 3.4), nausea (Analysis 3.5) or vomiting (Analysis 3.6). However, fewer episodes of diarrhoea occurred (Analysis 3.7) (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.06 to 4.61) when 200 μg misoprostol was administered vaginally compared to 400 μg misoprostol, orally.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24 hours.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 3 Surgical evacuation.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 4 Pain.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 5 Nausea.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 6 Vomiting.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 7 Diarrhoea.

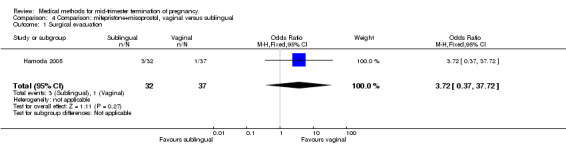

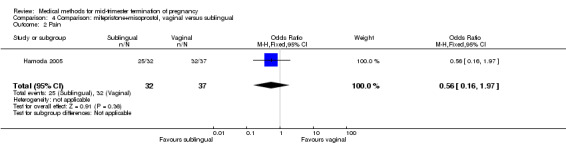

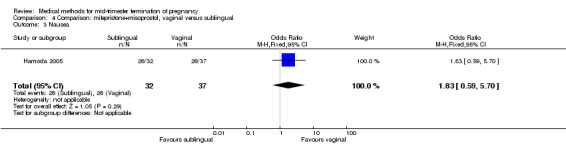

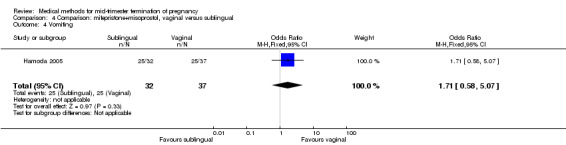

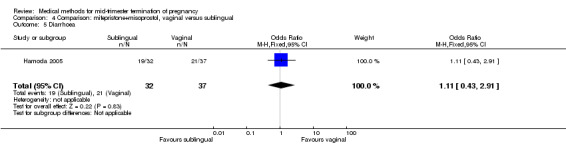

Comparison 4: vaginal use compared to sublingual use of misoprostol

In this comparison, one trial (Hamoda 2005) was included. In total, 69 women were eligible for analyses. The comparison was made between the sublingual use of 600 μg of misoprostol and the vaginal use of 800 μg, both combined with 200 mg mifepristone. In regards to the induction‐to‐the abortion interval, no mean or SD was provided and thus precluded inclusion of these data in a meta‐analysis. The median and range of the sublingual group (median 5.27, range 0.55 to 29.35) and of the vaginal group (median 5.40, range 2.10 to 13.00) showed no significant difference (P = 0.95) for the abortion interval. In addition, no difference between the sublingual and vaginal use was found in terms of the need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 4.1) or side‐effects such as pain (Analysis 4.2), nausea (Analysis 4.3), vomiting (Analysis 4.4) or diarrhoea (Analysis 4.5).

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 1 Surgical evacuation.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 2 Pain.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 3 Nausea.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 4 Vomiting.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.

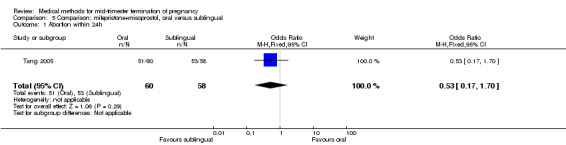

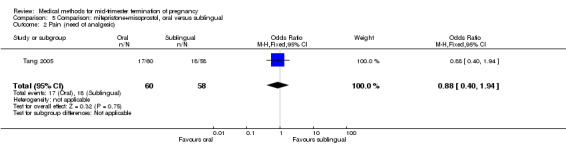

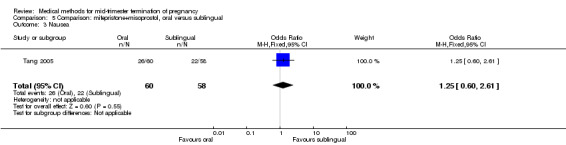

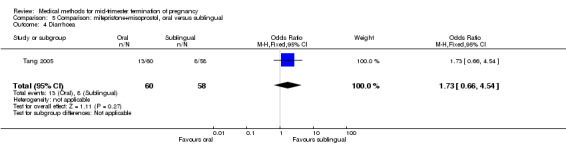

Comparison 5: oral use compared to sublingual use of misoprostol

In this comparison, one trial (Tang 2005) was included. In total, 118 women were eligible for analysis. Tang 2005 compared the oral and sublingual use of 400 μg of misoprostol in combination with 200 mg of mifepristone. Both groups received oral or sublingual placebo tablets. In regards to the induction‐to‐the abortion interval, no mean or SD was provided and thus precluded inclusion of these data in a meta‐analysis. The sublingual group (median 5.5, range 1.4 to 43.2) aborted in a shorter time interval when compared to the oral group (median 7.5, range 2.4 to 38.8) (P = 0.009). No difference was found in regards to the abortion rate within 24 hours (Analysis 5.1) or side‐effects such as pain (Analysis 5.2), nausea (Analysis 5.3) or diarrhoea (Analysis 5.4).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, oral versus sublingual, Outcome 1 Abortion within 24h.

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, oral versus sublingual, Outcome 2 Pain (need of analgesic).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, oral versus sublingual, Outcome 3 Nausea.

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol, oral versus sublingual, Outcome 4 Diarrhoea.

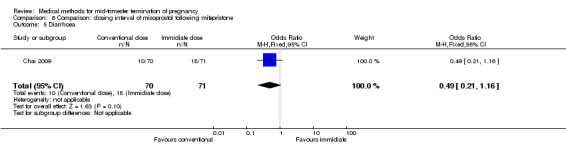

Comparison 6: dosing interval of misoprostol following mifepristone administration

One trial (Chai 2009) was included in this comparison. There were 141 women eligible for analyses. No difference was found in the abortion rate within 24 hours (Analysis 6.1), need of surgical evacuations (Analysis 6.2), or side‐effects of pain (Analysis 6.3), nausea (Analysis 6.4) and diarrhoea (Analysis 6.5). All patients from one centre had dilatation and curettage the day following abortion, as it was the routine practice in that hospital. These patients were not included in Analysis 6.2.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Comparison: dosing interval of misoprostol following mifepristone, Outcome 1 Abortion within 24 hours.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Comparison: dosing interval of misoprostol following mifepristone, Outcome 2 Surgical evacuation.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Comparison: dosing interval of misoprostol following mifepristone, Outcome 3 Pain (need for analgesia).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Comparison: dosing interval of misoprostol following mifepristone, Outcome 4 Nausea.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Comparison: dosing interval of misoprostol following mifepristone, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.

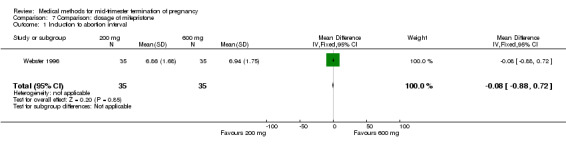

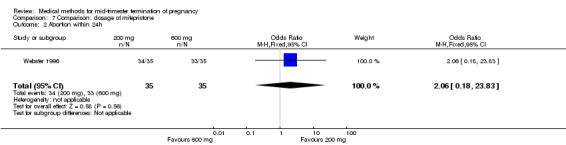

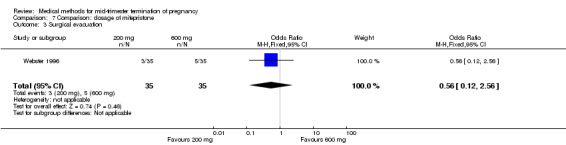

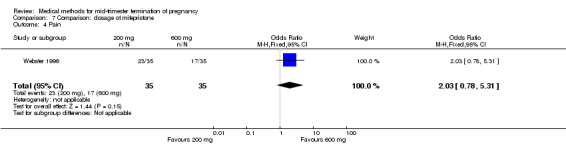

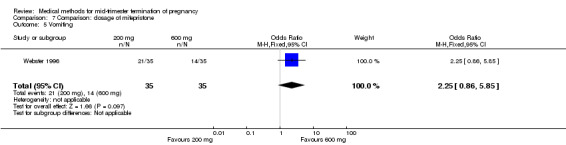

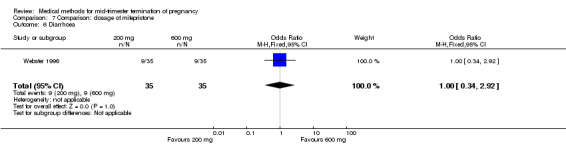

Comparison 7: dose of mifepristone before the administration of misoprostol

One trial (Webster 1996) was included in this comparison. In total, 70 women were eligible for analyses. No difference was found in the induction of the abortion interval (Analysis 7.1), abortion rate within 24 hours (Analysis 7.2), need of surgical evacuation (Analysis 7.3) or side‐effects of pain (Analysis 7.4), vomiting (Analysis 7.5) or diarrhoea (Analysis 7.6).

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Comparison: dosage of mifepristone, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Comparison: dosage of mifepristone, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24h.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Comparison: dosage of mifepristone, Outcome 3 Surgical evacuation.

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Comparison: dosage of mifepristone, Outcome 4 Pain.

7.5. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Comparison: dosage of mifepristone, Outcome 5 Vomiting.

7.6. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Comparison: dosage of mifepristone, Outcome 6 Diarrhoea.

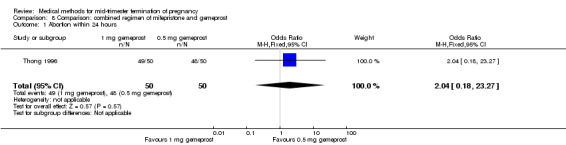

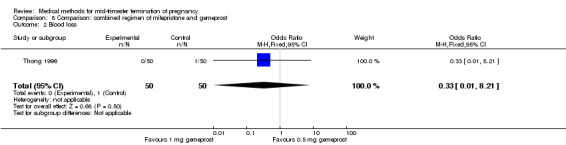

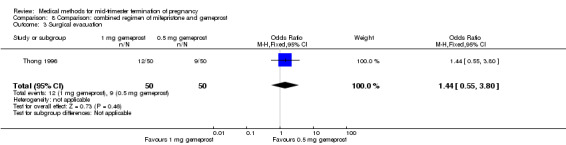

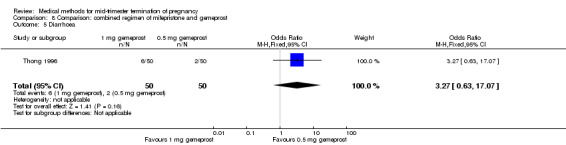

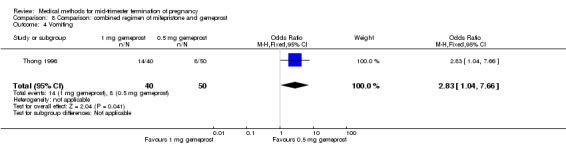

Comparison 8: regimen mifepristone + gemeprost 1.0 mg versus mifepristone + gemeprost 0.5 mg

One trial (Thong 1996) was included in this comparison. There were 100 women eligible for analysis. No difference was found in the abortion rate within 24 hours (Analysis 8.1), excessive blood loss (Analysis 8.2), need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 8.3) or episodes of diarrhoea (Analysis 8.5). When patients were given 0.5 mg gemeprost rather than 1 mg, they experienced fewer episodes of vomiting (Analysis 8.4) (OR 2.83, 95% CI 1.04 to 7.66).

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Comparison: combined regimen of mifepristone and gemeprost, Outcome 1 Abortion within 24 hours.

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Comparison: combined regimen of mifepristone and gemeprost, Outcome 2 Blood loss.

8.3. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Comparison: combined regimen of mifepristone and gemeprost, Outcome 3 Surgical evacuation.

8.5. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Comparison: combined regimen of mifepristone and gemeprost, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.

8.4. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Comparison: combined regimen of mifepristone and gemeprost, Outcome 4 Vomiting.

Comparisons 9 to 11: misoprostol versus another prostaglandin

Four trials with seven comparisons (Makhlouf 2003; Nuutila 1997 a; Nuutila 1997 b; Su 2005; Wong 1998) were included. Nuutila compared three interventions, that is, two doses of vaginal misoprostol and vaginal gemeprost. For this reason, this trial was considered for each of the different comparisons (see Characteristics of included studies).

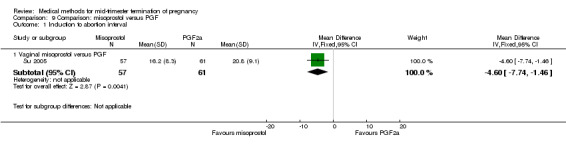

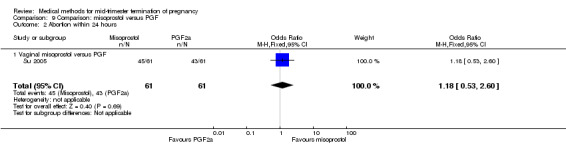

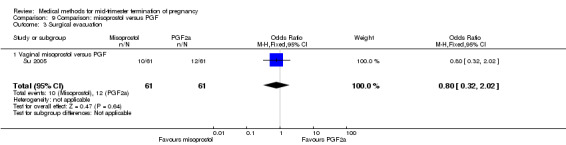

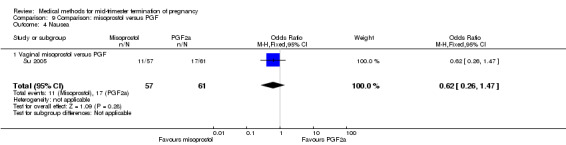

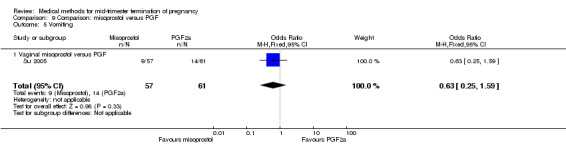

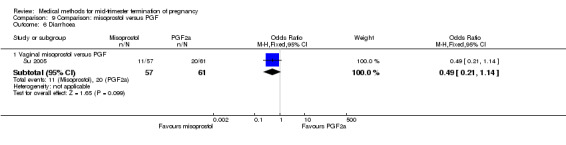

Comparison 9: misoprostol versus intra‐amniotic PGF2α

In this comparison, one trial was included (Su 2005). In total, 125 women were eligible for analysis. Su 2005 compared the use of vaginal misoprostol with the use of intra‐amniotic PGF2α. Vaginal misoprostol was superior to intra‐amniotic PGF2α (MD ‐4.60, 95% CI ‐7.74 to ‐1.46) (Analysis 9.1) regarding the induction to the abortion interval. No difference was found between the groups in relation to the abortion completion rate (Analysis 9.2), need for surgical evacuations (Analysis 9.3), nausea (Analysis 9.4), vomiting (Analysis 9.5) or diarrhoea (Analysis 9.6).

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Comparison: misoprostol versus PGF, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Comparison: misoprostol versus PGF, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24 hours.

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Comparison: misoprostol versus PGF, Outcome 3 Surgical evacuation.

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Comparison: misoprostol versus PGF, Outcome 4 Nausea.

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Comparison: misoprostol versus PGF, Outcome 5 Vomiting.

9.6. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Comparison: misoprostol versus PGF, Outcome 6 Diarrhoea.

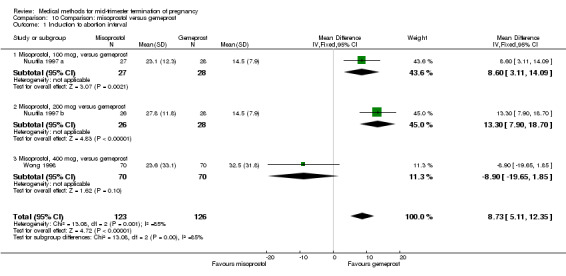

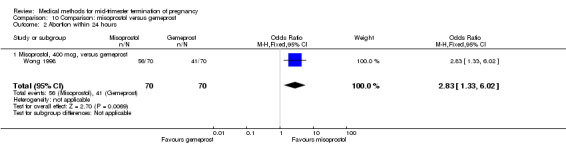

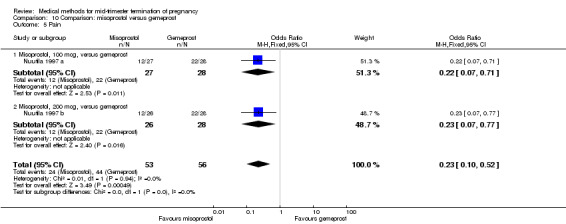

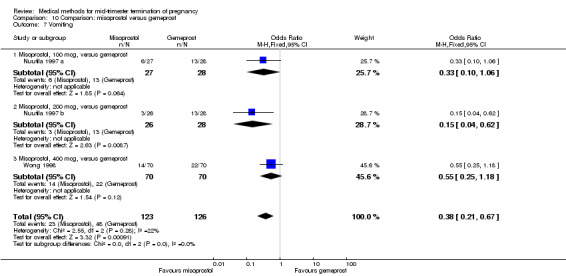

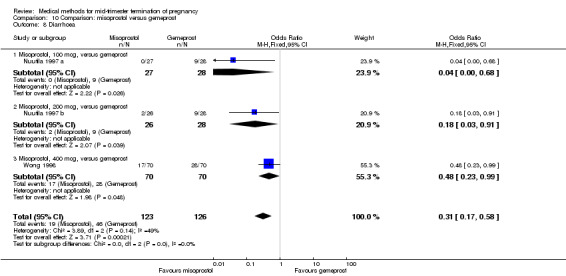

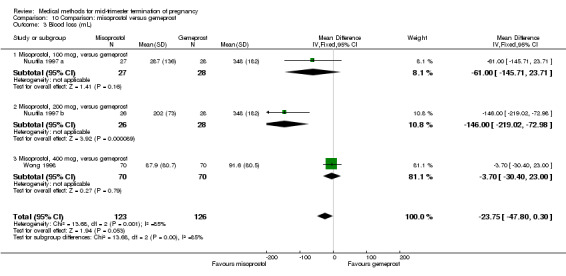

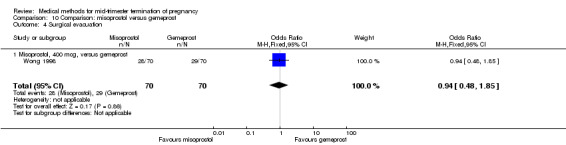

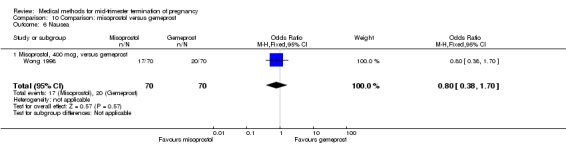

Comparison 10: misoprostol versus PGE1 (gemeprost)

In this comparison, two trials with three comparisons were included (Nuutila 1997 a; Nuutila 1997 b; Wong 1998). In total, 249 women were eligible for analysis. The largest trial in this analysis was conducted by Wong 1998, comparing the vaginal use of misoprostol, 400 μg every 4 hours, to the vaginal use of gemeprost. When misoprostol was used at very low doses (100 μg) (MD 8.60, 95% CI 3.11 to 14.09) or 200 μg (MD 13.30, 95% CI 7.90 to 18.70) every 6 or 12 hours, respectively, gemeprost was superior (Analysis 10.1). In contrast, when misoprostol was used at a higher dose (400 μg) (OR 2.83, 95% CI 1.33 to 6.02) every 3 or 6 hours, more women aborted within 24 hours in comparison to gemeprost (Analysis 10.2). In regards to the side‐effects, women who received misoprostol experienced less pain (100 μg) (OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.71) or 200 μg (OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.77), vomiting (misoprostol 200 μg, OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.62) and diarrhoea (100 μg, OR 0.04, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.68) or 200 μg (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.91) (Analysis 10.5; Analysis 10.7; Analysis 10.8). Moreover, the amount of blood loss was decreased when women received 200 μg misoprostol when compared to gemeprost (Analysis 10.3) (OR ‐146.00, 95% CI ‐219.02 to ‐72.98). No difference was found between the groups in relation to the need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 10.4) or nausea (Analysis 10.6).

10.1. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Comparison: misoprostol versus gemeprost, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

10.2. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Comparison: misoprostol versus gemeprost, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24 hours.

10.5. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Comparison: misoprostol versus gemeprost, Outcome 5 Pain.

10.7. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Comparison: misoprostol versus gemeprost, Outcome 7 Vomiting.

10.8. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Comparison: misoprostol versus gemeprost, Outcome 8 Diarrhoea.

10.3. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Comparison: misoprostol versus gemeprost, Outcome 3 Blood loss (mL).

10.4. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Comparison: misoprostol versus gemeprost, Outcome 4 Surgical evacuation.

10.6. Analysis.

Comparison 10 Comparison: misoprostol versus gemeprost, Outcome 6 Nausea.

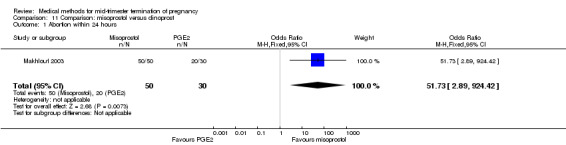

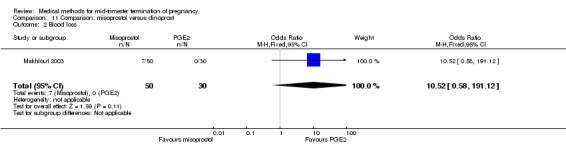

Comparison 11: misoprostol versus PGE2 (dinoprostone)

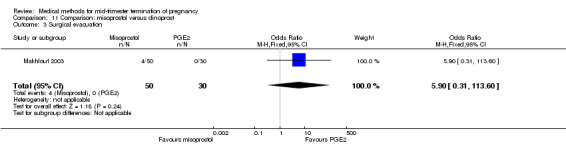

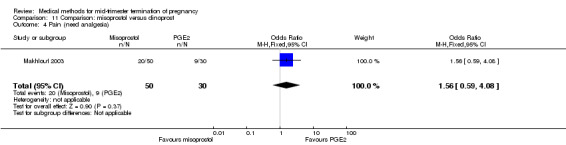

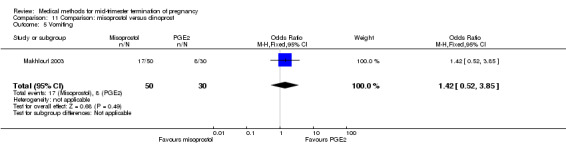

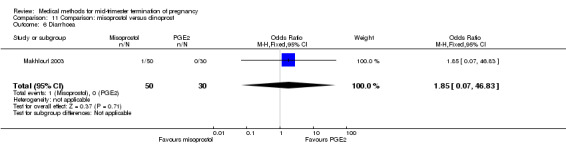

In this comparison, one trial was included (Makhlouf 2003). In total, 80 women were eligible for analysis. More women who were given misoprostol, 100 μg every four hours, aborted within 24 hours when compared to PGE2, 6 mg every six hours (Analysis 11.1) (OR 51.73, 95% CI 2.89 to 924.42). There was no difference regarding blood loss (Analysis 11.2), need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 11.3) or side‐effects of pain (Analysis 11.4), vomiting (Analysis 11.5) or diarrhoea (Analysis 11.6) between the groups.

11.1. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Comparison: misoprostol versus dinoprost, Outcome 1 Abortion within 24 hours.

11.2. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Comparison: misoprostol versus dinoprost, Outcome 2 Blood loss.

11.3. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Comparison: misoprostol versus dinoprost, Outcome 3 Surgical evacuation.

11.4. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Comparison: misoprostol versus dinoprost, Outcome 4 Pain (need analgesia).

11.5. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Comparison: misoprostol versus dinoprost, Outcome 5 Vomiting.

11.6. Analysis.

Comparison 11 Comparison: misoprostol versus dinoprost, Outcome 6 Diarrhoea.

Comparisons 12 to 13: routes of misoprostol for misoprostol used alone

In this comparison, six trials with two comparisons (Akoury 2004; Bebbington 2002; Behrashi 2008; Bhattacharjee 2008; Tang 2004; von Hertzen 2009) were included.

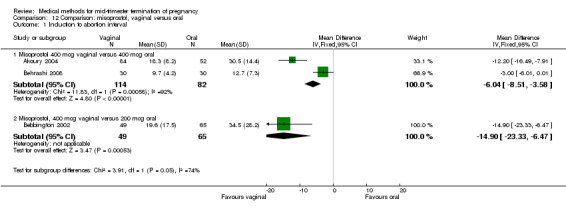

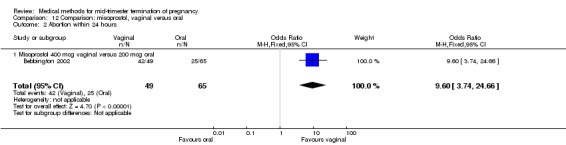

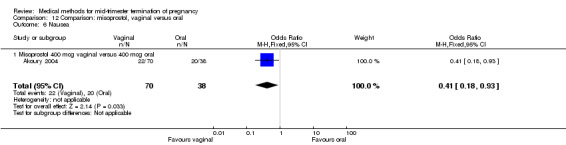

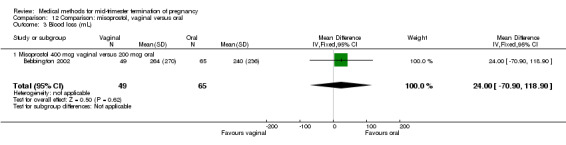

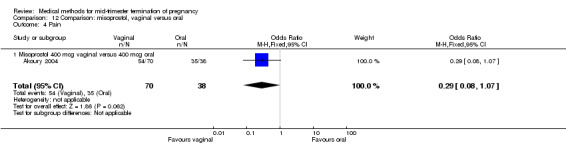

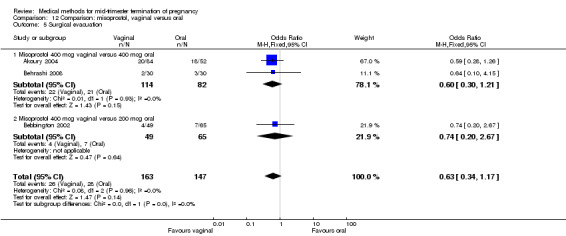

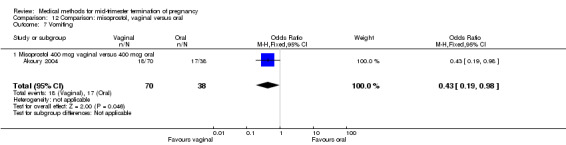

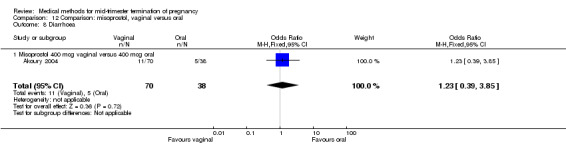

Comparison 12: vaginal use of misoprostol versus the oral use of misoprostol

In this comparison, three trials were included (Akoury 2004; Bebbington 2002; Behrashi 2008). In total, 310 women were eligible for analysis. The largest trial was conducted by Akoury, comparing the oral and vaginal use of misoprostol and the intra‐amniotic use of PGF2α. The vaginal administration of misoprostol was superior to the oral route (Analysis 12.1), at both a lower dose (200 μg) (mean difference (MD) ‐14.90, 95% CI ‐23.33 to ‐6.47) and a higher dose (400 μg) (MD ‐6.04, 95% CI ‐8.51 to ‐3.58). The abortion rate after 24 hours with vaginal use was also superior to the oral use of 200 μg of misoprostol (OR 9.60, 95% CI 3.74 to 24.66) (Analysis 12.2). Fewer women experienced nausea when the misoprostol was given vaginally when compared to the oral use of 400 μg of misoprostol (Analysis 12.6) (OR 0.41, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.93). No difference was found between the groups in regard to the amount of blood loss (Analysis 12.3), pain (Analysis 12.4), need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 12.5), vomiting (Analysis 12.7) or diarrhoea (Analysis 12.8).

12.1. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

12.2. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24 hours.

12.6. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 6 Nausea.

12.3. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 3 Blood loss (mL).

12.4. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 4 Pain.

12.5. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 5 Surgical evacuation.

12.7. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 7 Vomiting.

12.8. Analysis.

Comparison 12 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus oral, Outcome 8 Diarrhoea.

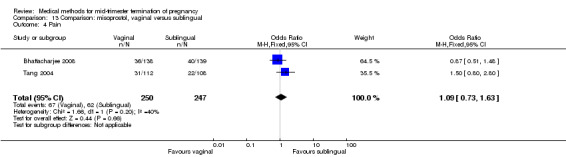

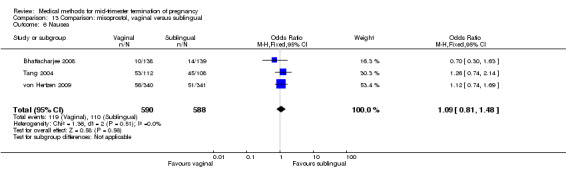

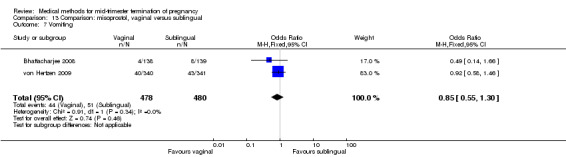

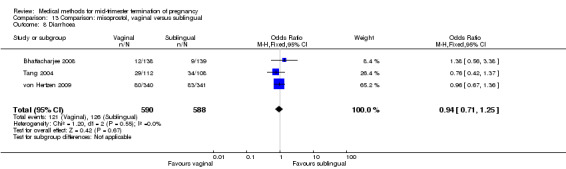

Comparison 13: vaginal use of misoprostol versus the sublingual use of misoprostol

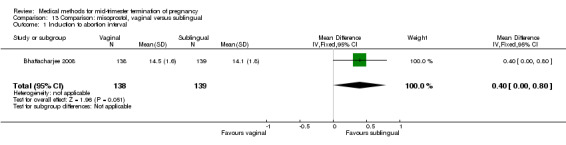

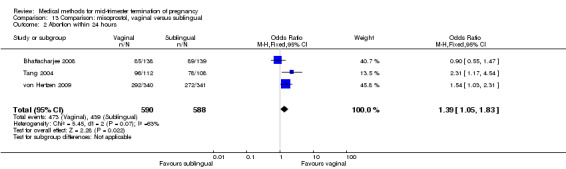

In this comparison, three trials were included (Bhattacharjee 2008; Tang 2004; von Hertzen 2009). In total, 1178 women were eligible for analysis. The largest trial was conducted by von Hertzen, comparing the vaginal use of 400 μg misoprostol to the sublingual use of 400 μg misoprostol with the use of placebo tablets. No difference was found between the vaginal or the sublingual use of misoprostol for the induction to abortion interval in one smaller study (Analysis 13.1). Von Hertzen was not included in this analyses, because no mean (SD) was provided. However, authors did provide median (range). In the vaginal group, the induction to abortion interval was longer (median 12.3, range 3.2 to 48.0) than the sublingual group (median 12.0, range 4.1 to 61.8). However, this difference was not significant. The abortion rate after 24 hours with vaginal use was superior to the sublingual use (Analysis 13.2) (OR 1.39, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.83). However, the significant heterogeneity for the analysis (Analysis 13.2) (I2 = 63%) must be noted despite use of identical regimens precludes confidence in these combined estimates. The heterogeneity between these data could potentially be explained by the difference in included numbers of multigravidas between both trials; Tang included 36% to 39%, while Bhattacharjee included 80% of women studied. Because of the possibility that among nulliparous women, vaginal misoprostol is associated with higher rates of complete abortion within 24 hours, the analysis were separated. Vaginal misoprostol is associated with significantly higher rates of complete abortion within 24 hours among nulliparous women (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.17 to 4.54), while among multiparous women, there is no difference between vaginal or sublingual administration (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.47). Von Hertzen conducted a stratified analysis by parity because there was a highly significant interaction of treatment by parity. When success rates at 24 h were analysed according to parity, vaginal administration was clearly superior to sublingual administration in nulliparous women (87.3% versus 68.5%) but the difference between treatments was not present among parous women: 84.7% (vaginal) versus 88.5% (sublingual).

13.1. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

13.2. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24 hours.

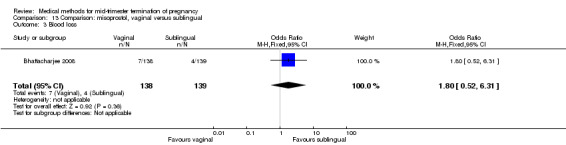

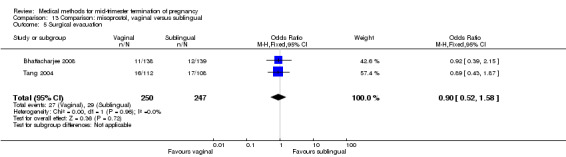

No differences were noted in the meta‐analysis for the occurrence of complications of blood loss (Analysis 13.3) or surgical evacuations (Analysis 13.5) or side‐effects of pain (Analysis 13.4), nausea (Analysis 13.6), vomiting (Analysis 13.7) or diarrhoea (Analysis 13.8).

13.3. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 3 Blood loss.

13.5. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 5 Surgical evacuation.

13.4. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 4 Pain.

13.6. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 6 Nausea.

13.7. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 7 Vomiting.

13.8. Analysis.

Comparison 13 Comparison: misoprostol, vaginal versus sublingual, Outcome 8 Diarrhoea.

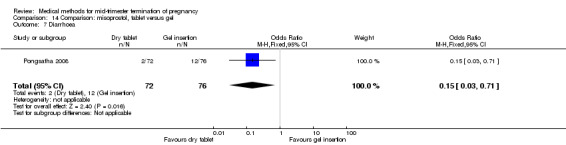

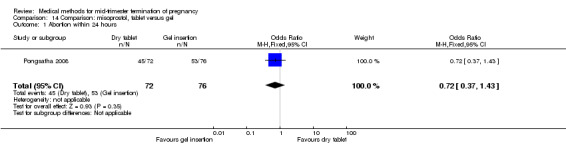

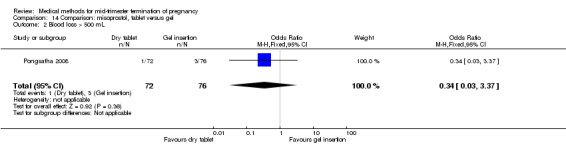

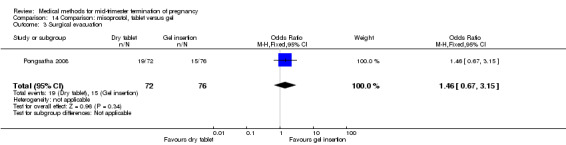

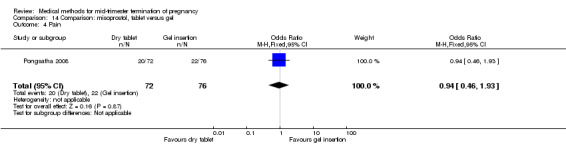

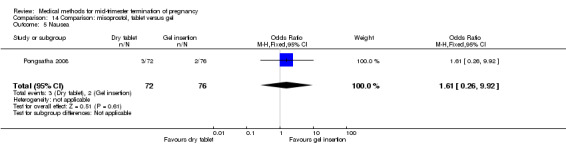

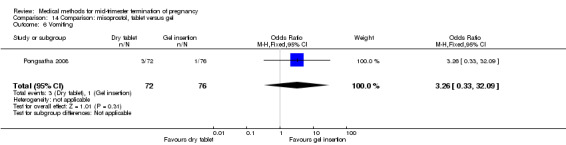

Comparison 14: misoprostol tablet insertion versus gel insertion

One trial (Pongsatha 2008) was included in this comparison. For analysis, 148 women were eligible for analysis. In terms of adverse outcomes, women who had misoprostol inserted with gel experienced more diarrhoea (Analysis 14.7) (OR 0.15, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.71). No significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of abortion within 24 hours (Analysis 14.1), excessive blood loss (Analysis 14.2), need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 14.3), pain (Analysis 14.4), nausea (Analysis 14.5) or vomiting (Analysis 14.6).

14.7. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Comparison: misoprostol, tablet versus gel, Outcome 7 Diarrhoea.

14.1. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Comparison: misoprostol, tablet versus gel, Outcome 1 Abortion within 24 hours.

14.2. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Comparison: misoprostol, tablet versus gel, Outcome 2 Blood loss > 500 mL.

14.3. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Comparison: misoprostol, tablet versus gel, Outcome 3 Surgical evacuation.

14.4. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Comparison: misoprostol, tablet versus gel, Outcome 4 Pain.

14.5. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Comparison: misoprostol, tablet versus gel, Outcome 5 Nausea.

14.6. Analysis.

Comparison 14 Comparison: misoprostol, tablet versus gel, Outcome 6 Vomiting.

Comparisons 15 to 16: time interval and dose of misoprostol or gemeprost

Four trials with two comparisons (Armatage 1996; Herabutya 2005; Wong 2000) were included.

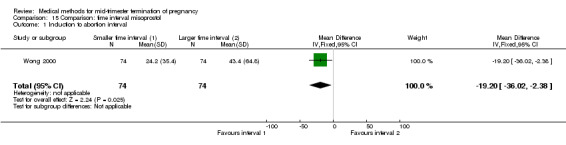

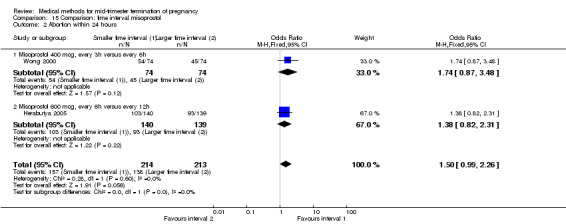

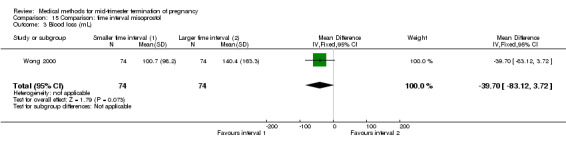

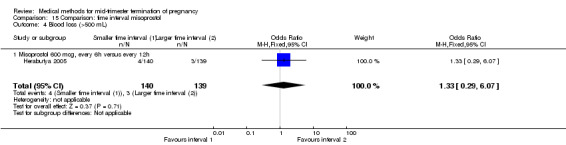

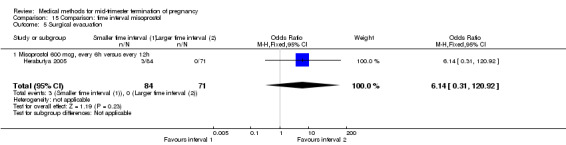

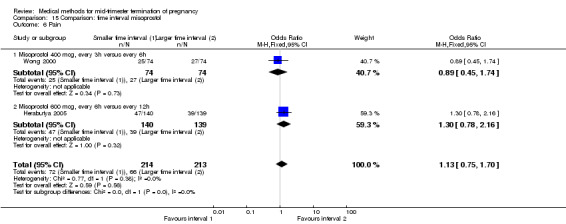

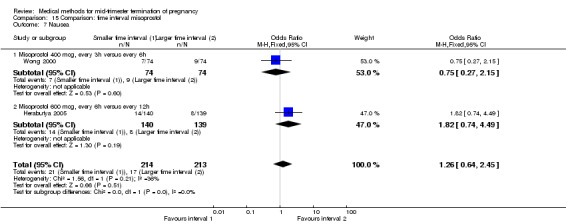

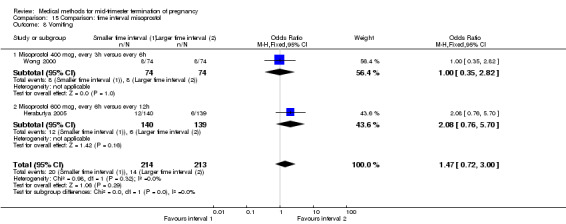

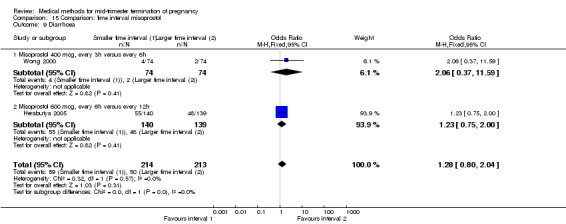

Comparison 15: time interval of misoprostol

Two trials (Herabutya 2005; Wong 2000) were included in this comparison. In total, 427 women were eligible for analysis. The largest trial in this analysis was conducted by Wong 2000 who examined the optimal time interval for the vaginal use of 400 μg misoprostol, either administered every three or every six hours. When the time interval was shorter, the interval to abortion was shorter (three hours) (Analysis 15.1) (MD ‐19.20, 95% CI ‐36.02 to ‐2.38) compared to the longer time interval (six hours). In regards to the induction to abortion interval, no mean or SD was provided by Herabutya 2005 and thus precluded inclusion of these data in the meta‐analysis. The median induction‐to‐abortion interval was 15.8 hrs (25, 75 centiles: 12, 26) and 16.0 hrs (25, 75 centiles: 12, 30) for the group given misoprostol with a shorter time interval and the group with a longer time interval respectively (P =0.80). No effect was found for the time interval in relation to the abortion rate within 24 hours (Analysis 15.2), excessive blood loss (Analysis 15.3; Analysis 15.4), need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 15.5), or side‐effects of pain (Analysis 15.6), nausea (Analysis 15.7), vomiting (Analysis 15.8) or diarrhoea (Analysis 15.9).

15.1. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Comparison: time interval misoprostol, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

15.2. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Comparison: time interval misoprostol, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24 hours.

15.3. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Comparison: time interval misoprostol, Outcome 3 Blood loss (mL).

15.4. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Comparison: time interval misoprostol, Outcome 4 Blood loss (>500 mL).

15.5. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Comparison: time interval misoprostol, Outcome 5 Surgical evacuation.

15.6. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Comparison: time interval misoprostol, Outcome 6 Pain.

15.7. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Comparison: time interval misoprostol, Outcome 7 Nausea.

15.8. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Comparison: time interval misoprostol, Outcome 8 Vomiting.

15.9. Analysis.

Comparison 15 Comparison: time interval misoprostol, Outcome 9 Diarrhoea.

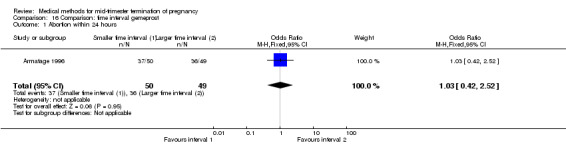

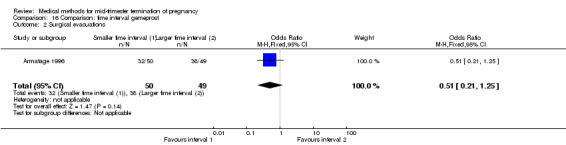

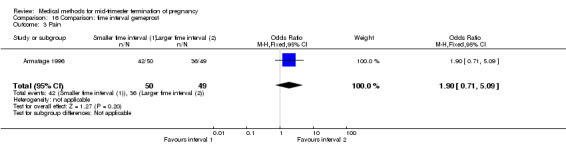

Comparison 16: time interval of gemeprost

One trial (Armatage 1996) was included in this comparison. In total, 99 women were eligible for analysis. In regards to the induction to abortion interval, no mean or SD was given, and thus precluded inclusion of these data in a meta‐analysis. The median induction‐to‐abortion interval was 16 hrs (25, 75 centiles: 12, 26) and 15 hrs (25, 75 centiles: 11.4, 28.5) for the group given gemeprost with a shorter time interval compared with the longer time interval, respectively (not significant). In addition, no significant difference was found between both groups in the abortion rate after 24 hours (Analysis 16.1), need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 16.2) or pain (Analysis 16.3).

16.1. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Comparison: time interval gemeprost, Outcome 1 Abortion within 24 hours.

16.2. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Comparison: time interval gemeprost, Outcome 2 Surgical evacuations.

16.3. Analysis.

Comparison 16 Comparison: time interval gemeprost, Outcome 3 Pain.

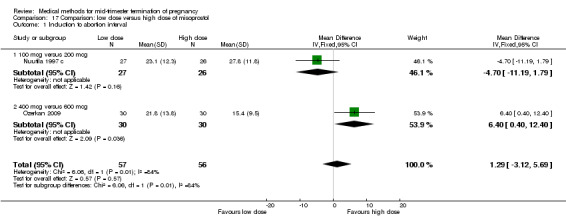

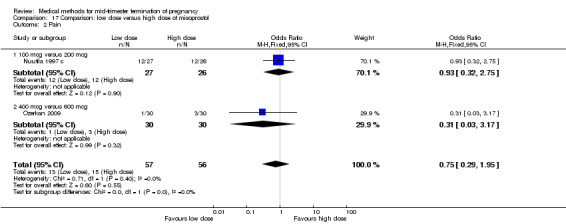

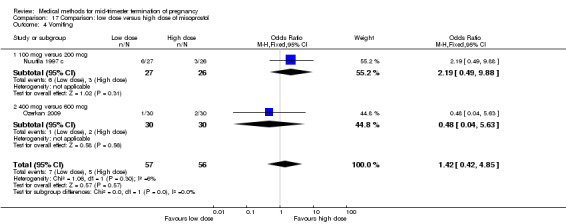

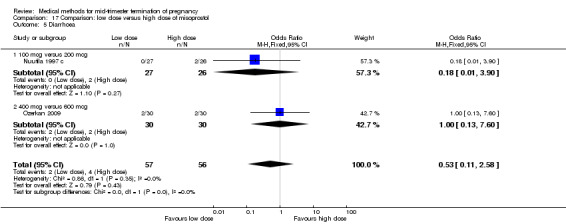

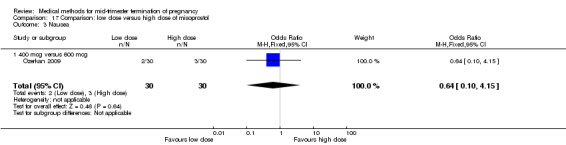

Comparison 17: low dose versus a higher dose of misoprostol

Two trials (Nuutila 1997 c; Ozerkan 2009) were included in this comparison. In total, 133 women were eligible for analyses. Ozerkan 2009 compared the use of 600 µg with the use of 400 µg of misoprostol. An initial first dose of 600 µg of misoprostol was found to be more effective than 400 µg (Analysis 17.1) (MD 6.40, 95% CI 0.40 to 12.40). While gestational age or parity were not found to be related to the duration of the termination procedure, a higher parity was shown to be correlated with a shorter induction to fetal‐expulsion period in the low dose, but not in the high dose group. Nuutila 1997 c compared the use of 100 µg of misoprostol to the use of 200 µg of misoprostol. The study found no difference between these groups in terms of the induction of the abortion interval (Analysis 17.1). The significant heterogeneity for the analysis (Analysis 17.1) (I2 = 84%) must be noted. This is most likely do to the different misoprostol doses the trials used. Both studies found no difference in the amount of pain (Analysis 17.2), and side effects such as vomiting (Analysis 17.4) and diarrhoea (Analysis 17.5).

17.1. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Comparison: low dose versus high dose of misoprostol, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

17.2. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Comparison: low dose versus high dose of misoprostol, Outcome 2 Pain.

17.4. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Comparison: low dose versus high dose of misoprostol, Outcome 4 Vomiting.

17.5. Analysis.

Comparison 17 Comparison: low dose versus high dose of misoprostol, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.

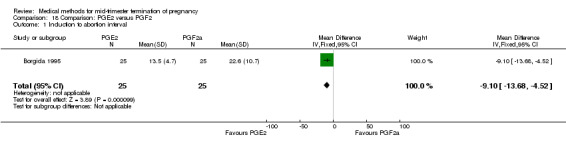

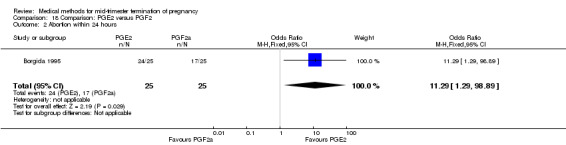

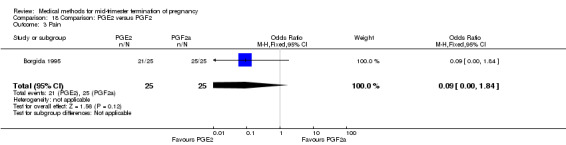

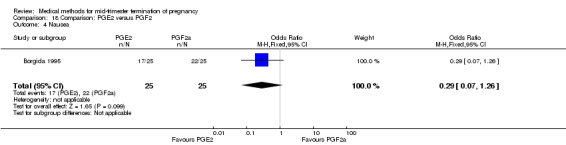

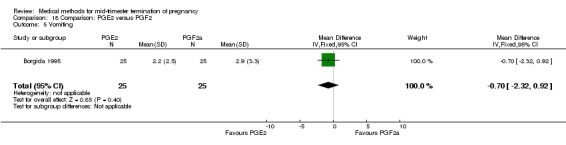

Comparisons 18 to 19: prostaglandin E2 versus prostaglandin F2α

Three trials with two comparisons (Borgida 1995; Sorensen 1984; Steyn 1993) were included.

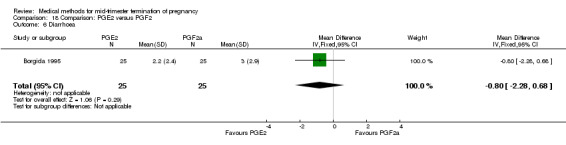

Comparison 18: prostaglandin E2 versus prostaglandin F2α

One trial (Borgida 1995) was included in this comparison. In total, 50 women were eligible for analysis. When women were given prostaglandin E2intravaginally, the interval to abortion was shorter (Analysis 18.1) (MD ‐9.10, 95% CI ‐13.68 to ‐4.52) when compared to the women receiving prostaglandin F2α intramuscularly. In addition, more women given prostaglandin E2 aborted within 24 hours (Analysis 18.2) (OR 11.29, 95% CI 1.29 to 98.89). No difference was found between the occurrence of side‐effects of pain (Analysis 18.3), nausea (Analysis 18.4), vomiting (Analysis 18.5) or diarrhoea (Analysis 18.6).

18.1. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Comparison: PGE2 versus PGF2, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

18.2. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Comparison: PGE2 versus PGF2, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24 hours.

18.3. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Comparison: PGE2 versus PGF2, Outcome 3 Pain.

18.4. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Comparison: PGE2 versus PGF2, Outcome 4 Nausea.

18.5. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Comparison: PGE2 versus PGF2, Outcome 5 Vomiting.

18.6. Analysis.

Comparison 18 Comparison: PGE2 versus PGF2, Outcome 6 Diarrhoea.

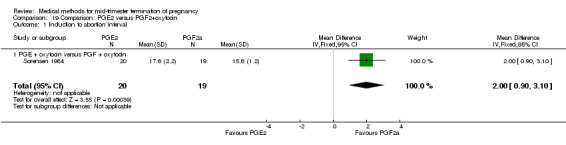

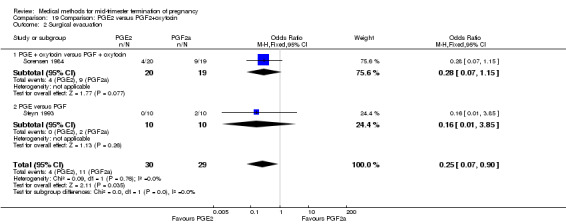

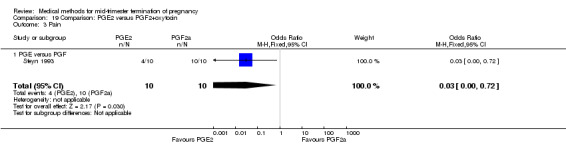

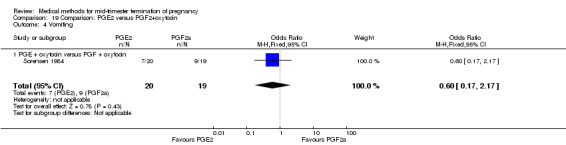

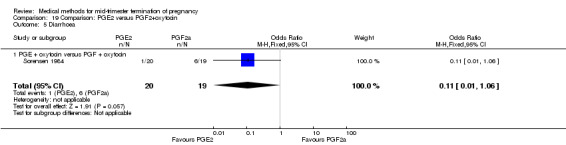

Comparison 19: prostaglandin E2 versus prostaglandin F2α + oxytocin

Two trials (Sorensen 1984; Steyn 1993) were included in this comparison. In total, 59 women were eligible for analysis. In regards to the induction‐to‐abortion interval, Steyn 1993 did not provide SDs, and thus precluded inclusion of these data in a meta‐analysis. The median induction to abortion interval was 38 hrs (range 19 to 61) and 23 hrs (range 11 to 54.5) for the intra‐amniotic prostaglandin F2α and the extra‐amniotic prostaglandin E2 group, respectively (not significant). When women were given prostaglandin E2 + oxytocin, the interval to abortion was longer (Analysis 19.1) (MD 2.00, 95% CI 0.90 to 3.10) compared to the women receiving prostaglandin F2α + oxytocin. Fewer surgical evacuations were performed in the prostaglandin E2 + oxytocin group (Analysis 19.2) (OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.90) and fewer women experienced pain (Analysis 19.3) (OR 0.03, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.72) when compared to the use of prostaglandin F2α + oxytocin. No difference was found regarding the episodes of vomiting or diarrhoea (Analysis 19.4; Analysis 19.5).

19.1. Analysis.

Comparison 19 Comparison: PGE2 versus PGF2+oxytocin, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

19.2. Analysis.

Comparison 19 Comparison: PGE2 versus PGF2+oxytocin, Outcome 2 Surgical evacuation.

19.3. Analysis.

Comparison 19 Comparison: PGE2 versus PGF2+oxytocin, Outcome 3 Pain.

19.4. Analysis.

Comparison 19 Comparison: PGE2 versus PGF2+oxytocin, Outcome 4 Vomiting.

19.5. Analysis.

Comparison 19 Comparison: PGE2 versus PGF2+oxytocin, Outcome 5 Diarrhoea.

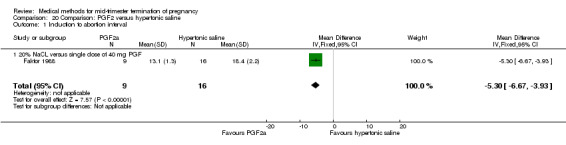

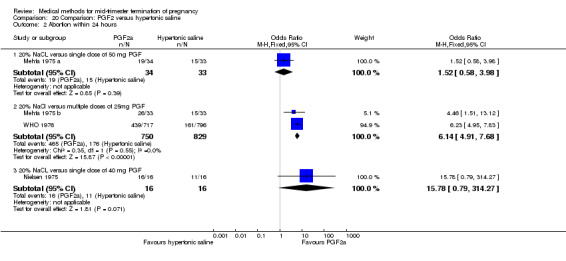

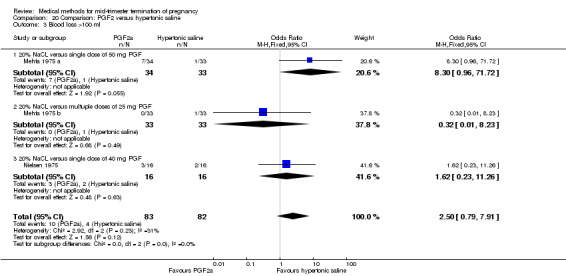

Comparison 20: intra‐amniotic instillation of prostaglandin F2α versus intra‐amniotic instillation of hypertonic saline (20%)

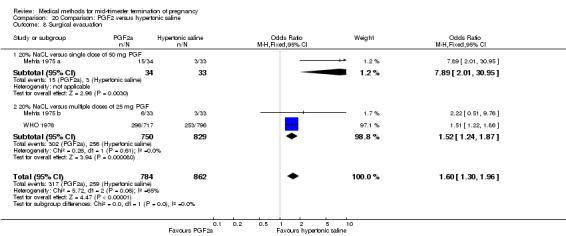

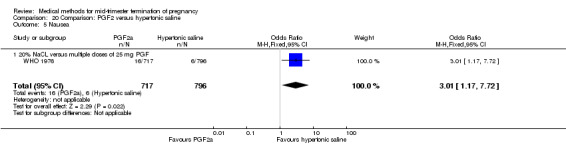

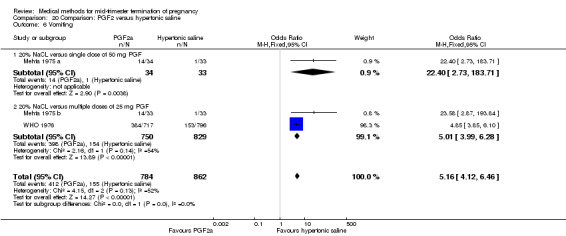

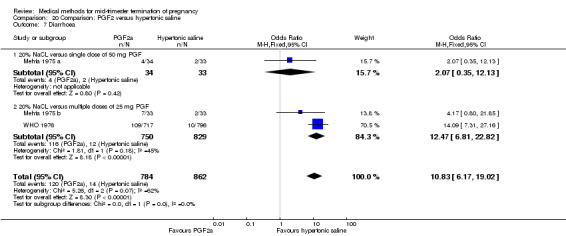

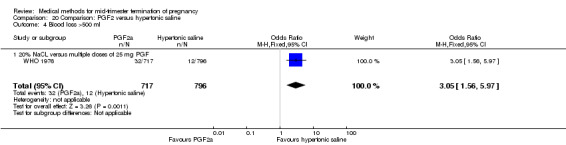

Four trials (Faktor 1988;Mehta 1975 a; Mehta 1975 b;Nielsen 1975;WHO 1976) were included for analysis. In total, 1703 women were eligible for analysis. The largest trial in this analysis was conducted by the WHO 1976, comparing the intra‐amniotic use of 25 mg of prostaglandin F2α to the intra‐amniotic instillation of 20% saline. In regards to the induction to abortion interval, Nielsen 1975. and the WHO trials did not provide standard deviations, and thus precluded inclusion of these data in a meta‐analysis. The median induction to abortion interval in the study by Nielsen 1975 was 21.5 hrs (ranges not given) and 14.2 hrs (ranges not given) for the hypertonic saline and the PGF2α group, respectively (P < 0.01). The median induction‐to‐abortion interval in the study by the WHO was 30.4 hrs (ranges not given) and 19.7 hrs (ranges not given) for the hypertonic saline and the PGF2α group respectively (P <0.001). Based on analysis of only 25 women, a single dose of 40 mg prostaglandin F2α proved to be more effective than 20% hypertonic saline in terms of induction‐ to‐ abortion interval (Analysis 20.1) (MD ‐5.30, 95% CI ‐6.67 to ‐3.93). The analysis of the abortion rate within 24 hours included 1678 women. Multiple doses of PGF2α proved to be more effective than 20% hypertonic saline (Analysis 20.2) (OR 6.14, 95% CI 4.91 to 7.68). On the other hand, women who received hypertonic saline experienced fewer complications, such as the need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 20.8) (single dose of 50 mg PGF2α OR 7.89, 95% CI 2.01 to 30.95; multiple doses of 25 mg PGF2α OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.24 to 1.87) episodes of nausea (Analysis 20.5) (OR 3.01, 95% CI 1.17 to 7.72), vomiting (Analysis 20.6) (single dose of 50 mg PGF2α OR 22.40, 95% CI 2.73 to 183.71; and multiple doses of 25 mg PGF OR 5.01, 95% CI 3.99 to 6.28) and diarrhoea (Analysis 20.7) (multiple doses of 25mg PGF2α OR 12.47, 95% CI 6.81 to 22.82). The WHO trial reported more episodes of excessive blood loss in women receiving PGF2α (Analysis 20.4) (OR 3.05, 95% CI 1.56 to 5.97).

20.1. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Comparison: PGF2 versus hypertonic saline, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

20.2. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Comparison: PGF2 versus hypertonic saline, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24 hours.

20.8. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Comparison: PGF2 versus hypertonic saline, Outcome 8 Surgical evacuation.

20.5. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Comparison: PGF2 versus hypertonic saline, Outcome 5 Nausea.

20.6. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Comparison: PGF2 versus hypertonic saline, Outcome 6 Vomiting.

20.7. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Comparison: PGF2 versus hypertonic saline, Outcome 7 Diarrhoea.

20.4. Analysis.

Comparison 20 Comparison: PGF2 versus hypertonic saline, Outcome 4 Blood loss >500 ml.

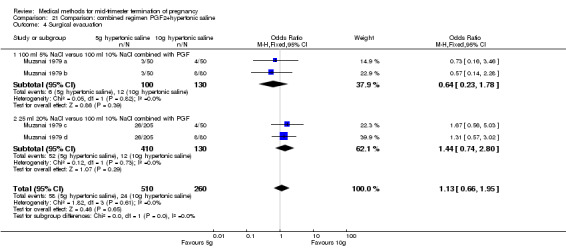

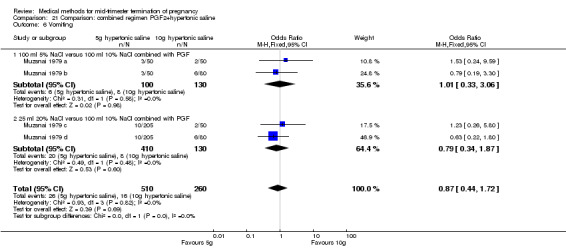

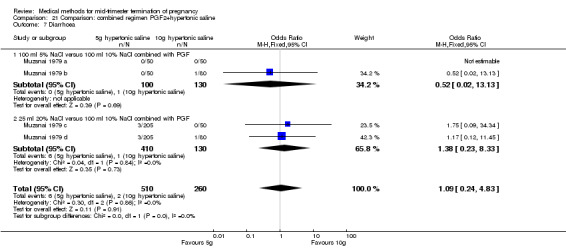

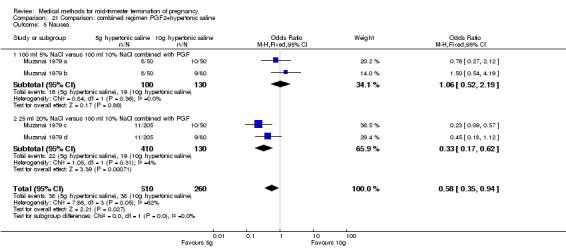

Comparison 21: combined regimen prostaglandin F2α and hypertonic saline

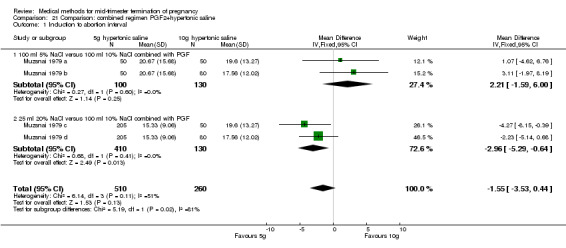

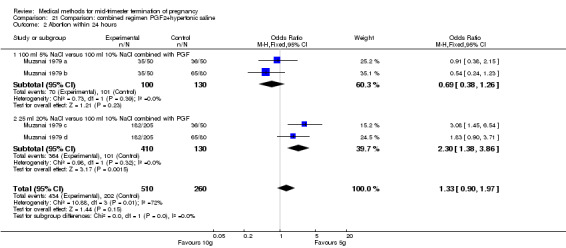

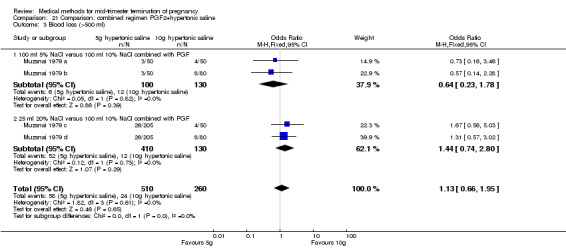

One trial (Muzsnai 1979 a; Muzsnai 1979 b; Muzsnai 1979 c; Muzsnai 1979 d) was included for analysis. In total, 770 women were eligible for analysis. The instillation of 25 ml 20% NaCl (5 g) + PGF2α (20 mg) was superior to the instillation of 100 ml 10% NaCl (10 g) + PGF2α (20 mg) (Analysis 21.1) in terms of the induction to the abortion interval (MD ‐2.96, 95% CI ‐5.29 to ‐0.64), but also in terms of the 24 hour abortion rate (OR 2.30, 95% CI 1.38 to 3.86) (Analysis 21.2). No significant difference was found between those who received 5 g of hypertonic saline versus 10 g in terms of excessive blood loss (Analysis 21.3), need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 21.4), vomiting (Analysis 21.6) and diarrhoea (Analysis 21.7). When given 25 ml of 20% hypertonic saline, women experienced less nausea (Analysis 21.5) (OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.62) than those who received 100 ml of 10% hypertonic saline.

21.1. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Comparison: combined regimen PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

21.2. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Comparison: combined regimen PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24 hours.

21.3. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Comparison: combined regimen PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 3 Blood loss (>500 ml).

21.4. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Comparison: combined regimen PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 4 Surgical evacuation.

21.6. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Comparison: combined regimen PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 6 Vomiting.

21.7. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Comparison: combined regimen PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 7 Diarrhoea.

21.5. Analysis.

Comparison 21 Comparison: combined regimen PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 5 Nausea.

Comparison 22: prostaglandin E1 (gemeprost) vaginally versus intra‐amniotic instillation of prostaglandin F2α + hypertonic saline

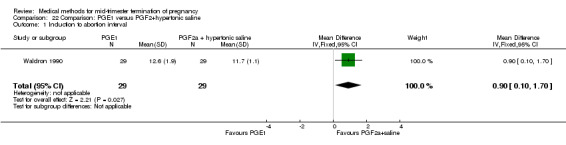

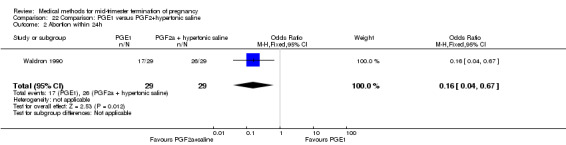

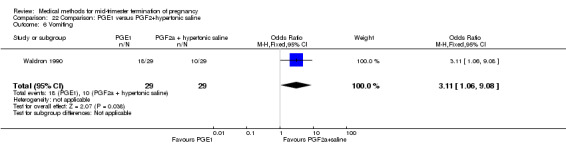

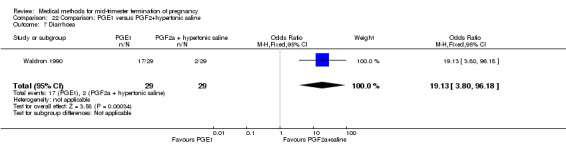

One trial (Waldron 1990) was included in this comparison. In total, 58 women were eligible for analysis. Women who had intra‐amniotic instillation of prostaglandin F2α + hypertonic saline aborted more rapidly than women who received vaginally administered gemeprost (Analysis 22.1) (MD 0.90, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.70) and the 24 hour abortion rate was significantly higher (Analysis 22.2) (OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.67). In addition, women who received gemeprost experienced more episodes of vomiting (Analysis 22.6) (OR 3.11, 95% CI 1.06 to 9.08) and diarrhoea (Analysis 22.7) (OR 19.13, 95% CI 3.80 to 96.18). No significant difference was found in terms of excessive blood loss (Analysis 22.3), need for surgical evacuation (Analysis 22.4) or pain (Analysis 22.5).

22.1. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Comparison: PGE1 versus PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

22.2. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Comparison: PGE1 versus PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24h.

22.6. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Comparison: PGE1 versus PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 6 Vomiting.

22.7. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Comparison: PGE1 versus PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 7 Diarrhoea.

22.3. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Comparison: PGE1 versus PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 3 Blood loss (>300ml).

22.4. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Comparison: PGE1 versus PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 4 Surgical evacuation.

22.5. Analysis.

Comparison 22 Comparison: PGE1 versus PGF2+hypertonic saline, Outcome 5 Pain (pethidine).

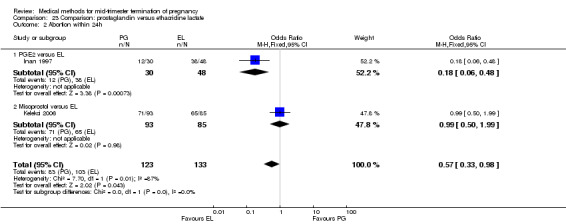

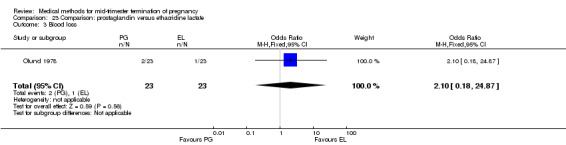

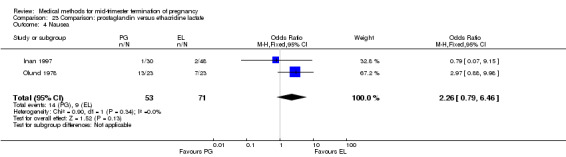

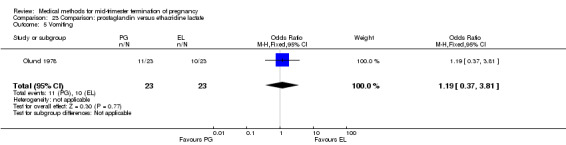

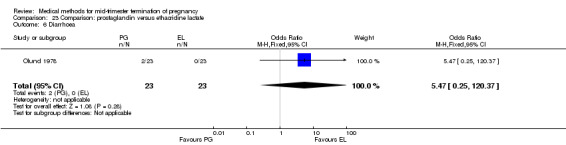

Comparison 23: prostaglandins versus ethacridine lactate

Three trials (Inan 1997; Kelekci 2006; Olund 1978) were included in this comparison. For analyses, 302 women were eligible. No significant difference in induction to abortion interval was found (Analysis 23.1). Olund 1978 provided no standard deviation and could therefore not enter our analysis. The mean and range of the abortion interval of the ethacridine lactate group (29.9, 23.9 to 47.2) and of the prostaglandin F2α group (26.7, 8.9 to 63.0) showed no significant difference. More women in the ethacridine lactate group aborted within 24 hours (Analysis 23.2) (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.48) in comparison to prostaglandin E2, but not in comparison to misoprostol. No differences were found in regard to the amount of blood loss (Analysis 23.3) or side‐effects, such as nausea (Analysis 23.4), vomiting (Analysis 23.5) or diarrhoea (Analysis 23.6). Kelekci 2006 provided no information about the side‐effects of each group, but found similar occurrences in both groups. Other side‐effects described by Inan 1997 included endometritis (ethacridine lactate group 4.1%, PGE2 group 3.3%; difference not significant).

23.1. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Comparison: prostaglandin versus ethacridine lactate, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

23.2. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Comparison: prostaglandin versus ethacridine lactate, Outcome 2 Abortion within 24h.

23.3. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Comparison: prostaglandin versus ethacridine lactate, Outcome 3 Blood loss.

23.4. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Comparison: prostaglandin versus ethacridine lactate, Outcome 4 Nausea.

23.5. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Comparison: prostaglandin versus ethacridine lactate, Outcome 5 Vomiting.

23.6. Analysis.

Comparison 23 Comparison: prostaglandin versus ethacridine lactate, Outcome 6 Diarrhoea.

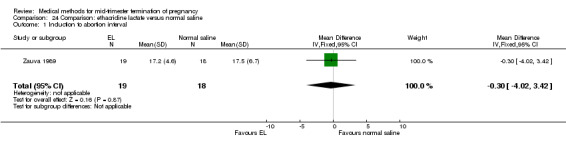

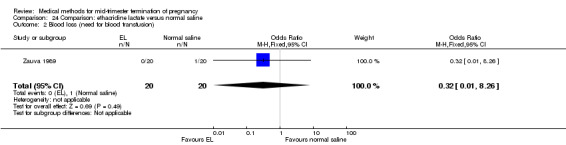

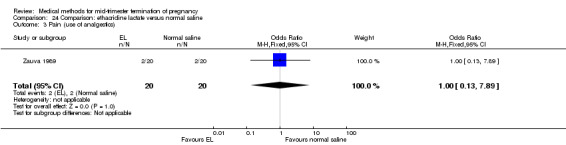

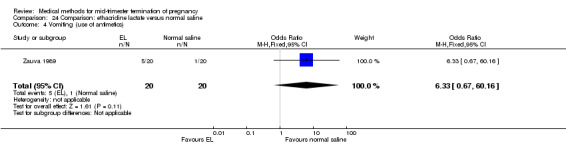

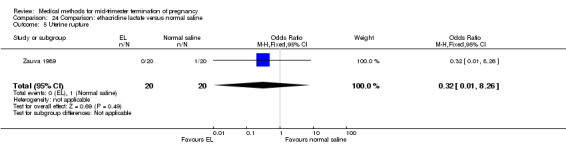

Comparison 24: ethacridine lactate versus normal saline

One trial (Zauva 1989) was included in this comparison. In total, 37 women were eligible for analysis. No differential effect was found between extra‐amniotic ethacridine lactate and extra‐amniotic normal saline regarding the induction‐to‐abortion interval (Analysis 24.1), excessive blood loss (Analysis 24.2), pain (Analysis 24.3), vomiting (Analysis 24.4) or rate of uterine rupture (Analysis 24.5).

24.1. Analysis.

Comparison 24 Comparison: ethacridine lactate versus normal saline, Outcome 1 Induction to abortion interval.

24.2. Analysis.

Comparison 24 Comparison: ethacridine lactate versus normal saline, Outcome 2 Blood loss (need for blood transfusion).

24.3. Analysis.

Comparison 24 Comparison: ethacridine lactate versus normal saline, Outcome 3 Pain (use of analgestics).

24.4. Analysis.

Comparison 24 Comparison: ethacridine lactate versus normal saline, Outcome 4 Vomiting (use of antimetics).

24.5. Analysis.

Comparison 24 Comparison: ethacridine lactate versus normal saline, Outcome 5 Uterine rupture.

Discussion

Second trimester medical abortion regimens have evolved greatly over the past 20 years with increasing availability of prostaglandin analogues and anti‐progesterone agents such as mifepristone. Older regimens such as instillation of hypertonic saline or prostaglandin F2α although effective in provoking abortion, were associated with higher rates of serious adverse events than are modern methods (Bygdeman and Gemzell‐Danielsson 2008).

Randomised comparisons included in this review demonstrate that misoprostol is the prostaglandin analogue of choice: it is as effective or more effective than other studied prostaglandins and has the preferable characteristics of heat stability and multiple administrative routes. However, in settings where prostaglandins are not available for second trimester medical abortion, extra‐amniotic instillation of ethacridine lactate may be an alternative (Comparisons 23, 24) (Hou 2010). However, limited information is available percentage of women needing a surgical intervention for incomplete abortion and the safety outcomes of ethacridine lactate, given the small number of subjects studied. When using extra‐amniotic instillation of drugs, the catheter tends to be expelled as the cervix dilates, before the abortion process is self‐sustaining. For this reason, supplementary infusions of oxytocin are commonly used (Kelekci 2006; WHO technical report series) which also increases the associated costs. Furthermore, intra‐amniotic injection of drugs is potentially dangerous as accidental injection into maternal tissue or placenta can result in local tissue damage or harmful absorption into the maternal circulation (WHO technical report series). For this reason, the drugs should only be given by skilled operators. Intra‐amniotic injection of drugs may also induce infection into the amniotic cavity (WHO technical report series).

Misoprostol when used alone is an effective inductive agent; however, it appears more efficient when combined with mifepristone, although the evidence from randomised trials is limited. In fact, there is only one relatively small randomised study (Kapp 2007) comparing the effect of misoprostol + mifepristone with misoprostol only (Comparison 2). This study demonstrated that the addition of mifepristone in second trimester abortion reduces the induction to abortion interval from 18 hours (95% CI 1 to 22) to 10 hours (95% CI 8 to12), while the occurrence of side‐effects in both groups was similar. Indirect evidence, however, suggests a beneficial effect of adding mifepristone to prostaglandin tablets or gel since the induction‐to‐abortion interval is generally shorter in regimens using mifepristone + prostaglandins (Comparisons 1, 3, 4, 5 and 7) than those using prostaglandins alone (Comparisons 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18 and 19). Additionally, mifepristone is known to potentiate the uterine effect of misoprostol and is superior to misoprostol alone in first trimester abortion.

Misoprostol may be administered by different routes, the oral route being the least effective (Comparisons 3, 4 and 5). For regimens using misoprostol, vaginal dosing appears to be the most efficient when compared to both oral and sublingual regimens. Among multiparous women undergoing medical abortion with misoprostol alone, sublingual administration appears equally effective as vaginal administration. No study of second trimester medical abortion has compared vaginal with buccal administration of misoprostol.

The optimal dose of vaginally administered misoprostol is difficult to ascertain since there are no randomised studies comparing various dosing schemes for vaginal administration. Four randomised clinical trials showed that the induction to abortion interval with 3‐hourly vaginal administration of prostaglandins was significantly shorter than 6‐hourly administration without significant increase in side‐effects (Comparisons 15 and 16).

There is insufficient data to make any gestational, age‐specific recommendations on the dosage and regimen for abortion. Since the uterus becomes more sensitive to prostaglandins with increasing gestational age, reducing the dosage or frequency of administration should be considered at later gestational ages (Ho 2007). The age range considered in this review includes 12 through 28 weeks of gestation. Overall, from the design of the included studies, there is no indication for confounding by gestational age.

Other considerations for second trimester medical abortion regimens which could not be addressed in this review include the effect on the abortion process of the use of pre‐procedure feticide to avoid the occurrence of a fetus with signs of life at abortion, and therapeutic strategies for women who have not aborted after 24 hours of treatment.

There are considerable differences in practices regarding the management of the placenta following the expulsion of the fetus. We considered surgical evacuation any procedure where an instrument was introduced into the uterine cavity. Indications for surgical evacuation include the removal of retained products of the placenta and heavy vaginal bleeding, where reported. Fewer women required surgical evacuation when misoprostol was administrated vaginally when compared to women having mid‐trimester abortion by intra‐amniotic instillation of PGF2α (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.87) (Comparison 9). Apart from the latter finding, there were no statistically significant differences in reported frequencies of surgical removal of the placenta among women undergoing misoprostol‐induced abortions when compared to other regimens.

Diarrhoea is the most common adverse reaction that has been reported consistently with misoprostol, but it is usually mild and self limiting. Nausea and vomiting may also occur and generally resolves in two to six hours (Tang 2007). Uterine rupture is a rare but serious complication of abortion in the second trimester of pregnancy, especially in women with a previous uterine scar (Berghella 2009). Uterine rupture is uncommon and did not occur during any of the included trials; thus, its relative risk with differing medical regimens are not informed by this review.

Summary of main results

Thirty‐six randomised controlled trials were included in the review. The included studies addressed the various agents for pregnancy termination and methods of administration which were grouped into 28 comparisons. When used alone, misoprostol is an effective inductive agent, though it appears to be more effective in combination with mifepristone.

Misoprostol is preferably administered vaginally, although among multiparous women sublingual administration appears equally effective. The optimal dose of vaginally administered misoprostol could not be determined, as no randomised studies could be identified. Low doses of misoprostol are associated with fewer side‐effects, while moderate doses are more efficient in completing abortion. Four randomised controlled trials showed that the induction to abortion interval with 3‐hourly vaginal administration of prostaglandins is significantly shorter than 6‐hourly administration without a significant increase in side‐effects.

Many studies reported the need for surgical evacuation in a considerable number of women undergoing mid‐trimester termination. Indications for surgical evacuation include the removal of retained products of the placenta and heavy vaginal bleeding. Fewer women required surgical evacuation when misoprostol was administrated vaginally when compared with those having intra‐amniotic instillation of PGF2a. Apart from the latter finding, there were no statistically significant differences in reported frequencies of surgical removal of the placenta among women undergoing misoprostol‐induced abortions when compared to other regimens. Diarrhoea was more common among women having misoprostol when compared to other agents. However, diarrhoea is reportedly mild and self limiting.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The results of this review fit well into the current practices of mid‐trimester termination of pregnancy.

Quality of the evidence

All randomised controlled trials, most of these being unblinded. Given the heterogeneity of the some studies included in the review, the internal validity of the findings is limited.

Potential biases in the review process

None.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Agree with recent Society for Family Planning Guidelines, in press.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The results of this review suggest that the most efficient regimen for medical abortion in the second trimester is the combination of mifepristone and misoprostol. If mifepristone is not available, misoprostol alone is a reasonable alternative. The available data suggest that vaginal administration is the most efficient route of administration, and 3‐hourly intervals of administration are more effective than 6‐hourly intervals. Meta‐analysis of the various randomised controlled trials on misoprostol was hampered by the heterogeneity in medical regimens used among the included trials. Included studies indicate that adverse effects of misoprostol are usually mild and dose dependant. Apart from pain resulting from uterine contractions, diarrhoea is the most common side‐effect that has been reported consistently with misoprostol. There are considerable differences in practices regarding the management of the placenta following the expulsion of the fetus.

Implications for research.

This review highlights the importance of developing a standardised medical method for women requesting mid‐trimester abortion. Further research is needed to evaluate the gestational‐age‐specific dosage of misoprostol for mid‐trimester abortion. In addition, more data are needed to guide medical and/or surgical strategies for women with a uterine scar resulting from prior hysterotomy (see Berghella 2009) and for those who failed to abort within 24 hours or five doses of misoprostol. Finally, more research is needed to evaluate the additional value, optimal dose and timing of mifepristone when used in combination with misoprostol.

Notes

None

Acknowledgements

None

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Comparison: mifepristone+misoprostol versus mifepristone+gemeprost.