Significance

Lepidoptera play key roles in many biological systems. Butterflies are hypothesized to have evolved contemporaneously with flowering plants, and moths are thought to have gained anti-bat defenses in response to echolocating predatory bats, but these hypotheses have largely gone untested. Using a transcriptomic, dated evolutionary tree of Lepidoptera, we demonstrate that the most recent common ancestor of Lepidoptera is considerably older than previously hypothesized. The oldest moths in crown Lepidoptera were present in the Carboniferous, some 300 million years ago, and began to diversify largely in synchrony with angiosperms. We show that multiple lineages of moths independently evolved hearing organs well before the origin of bats, rejecting the hypothesis that lepidopteran hearing organs arose in response to these predators.

Keywords: Lepidoptera, coevolution, phylogeny, angiosperms, bats

Abstract

Butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) are one of the major superradiations of insects, comprising nearly 160,000 described extant species. As herbivores, pollinators, and prey, Lepidoptera play a fundamental role in almost every terrestrial ecosystem. Lepidoptera are also indicators of environmental change and serve as models for research on mimicry and genetics. They have been central to the development of coevolutionary hypotheses, such as butterflies with flowering plants and moths’ evolutionary arms race with echolocating bats. However, these hypotheses have not been rigorously tested, because a robust lepidopteran phylogeny and timing of evolutionary novelties are lacking. To address these issues, we inferred a comprehensive phylogeny of Lepidoptera, using the largest dataset assembled for the order (2,098 orthologous protein-coding genes from transcriptomes of 186 species, representing nearly all superfamilies), and dated it with carefully evaluated synapomorphy-based fossils. The oldest members of the Lepidoptera crown group appeared in the Late Carboniferous (∼300 Ma) and fed on nonvascular land plants. Lepidoptera evolved the tube-like proboscis in the Middle Triassic (∼241 Ma), which allowed them to acquire nectar from flowering plants. This morphological innovation, along with other traits, likely promoted the extraordinary diversification of superfamily-level lepidopteran crown groups. The ancestor of butterflies was likely nocturnal, and our results indicate that butterflies became day-flying in the Late Cretaceous (∼98 Ma). Moth hearing organs arose multiple times before the evolutionary arms race between moths and bats, perhaps initially detecting a wide range of sound frequencies before being co-opted to specifically detect bat sonar. Our study provides an essential framework for future comparative studies on butterfly and moth evolution.

Butterflies and moths (Lepidoptera) are 1 of the 4 major insect superradiations, with close to 160,000 described species (1, 2). They thrive in nearly all terrestrial ecosystems, feature a wide spectrum of ecological adaptations, and are inextricably connected to the natural histories of many plants, predators, and parasitoids. The extraordinary diversity of Lepidoptera is presumed to be tightly linked to the rise of flowering plants (3), and the association between butterflies and angiosperms served as the foundation for Ehrlich and Raven's theory of coevolution (4). Prior studies of lepidopteran evolution postulated that the larvae of the earliest lineages were internal feeders on nonvascular land plants and their adults had mandibulate chewing mouthparts (5, 6). The remaining majority of Lepidoptera are hypothesized to have diversified largely in parallel with angiosperms, with larvae that are external plant feeders and adults that have tube-like proboscides (7). The proboscis promoted access to flower nectar and may have led to the ability of these ancestors to disperse to greater distances and colonize new host plants.

Nocturnal moths represent >75% of Lepidoptera species diversity (8), and they are thought to have proliferated in the Late Cretaceous when they evolved bat-detecting ultrasonic hearing organs (9, 10). At least 10 lepidopteran families have these ears (11), which are on different parts of the body in different families (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The timing of when ears arose has remained untested because a stable, dated phylogenetic framework for the Lepidoptera has been unavailable. Previous phylogenetic studies that examined macroevolutionary patterns of Lepidoptera (e.g., refs. 6 and 12–17) lacked sufficient genetic data and carefully evaluated fossil sampling to confidently resolve the evolutionary history of the order.

We constructed the largest dataset of transcriptomes for phylogenetic inference of the order, comprising 2,098 protein-coding genes sampled from 186 extant Lepidoptera species. Using different dating schemes and a set of critically evaluated fossils, we conducted multiple fossil-calibrated phylogenetic analyses. With the dated tree, we examined the evolution and timing of angiosperm feeding, ultrasonic hearing organs, and adult diel activity. Our phylogenetic analyses produced a robust reconstruction of the evolutionary history and timing of these key ecological adaptations in this megadiverse insect order.

Results and Discussion

We assembled de novo characterized transcriptomes and genomes of 186 Lepidoptera species, representing 34 superfamilies, and 17 outgroup species (Datasets S1–S4). Phylogenetic analyses were based on nucleotide and amino acid datasets of 2,098 protein coding gene alignments (2,249,363 nucleotides and 749,791 amino acid sites). In addition to maximum likelihood (ML) tree reconstruction, we conducted multispecies coalescence (MSC) analyses and 4-cluster likelihood mapping (FcLM) (18) to alleviate limitations that exist with traditional support metrics, and evaluate the presence of alternative, potentially conflicting signals in our datasets. ML analyses resulted in statistically well-supported trees (SI Appendix, Figs. S2–S8), which were largely corroborated by MSC results (SI Appendix, Figs. S9 and S10 and Dataset S5). The FcLM analyses (Datasets S6–S8) indicated that there was little confounding signal. The placement of a few lineages remains uncertain (SI Appendix, Fig. S11 and Dataset S9), but they do not significantly impact our conclusions. All 8 divergence time analyses resulted in largely congruent age estimates (SI Appendix, Figs. S12–S32 and Datasets S9–S11). The difference between the oldest and youngest median age estimates for crown Lepidoptera was ∼21 Ma, which is ∼7% of the median age presented in Fig. 1. When the same calculations are performed on 27 other key lepidopteran crown nodes, only 1 had a median age estimate difference >26 Ma (Dataset S11).

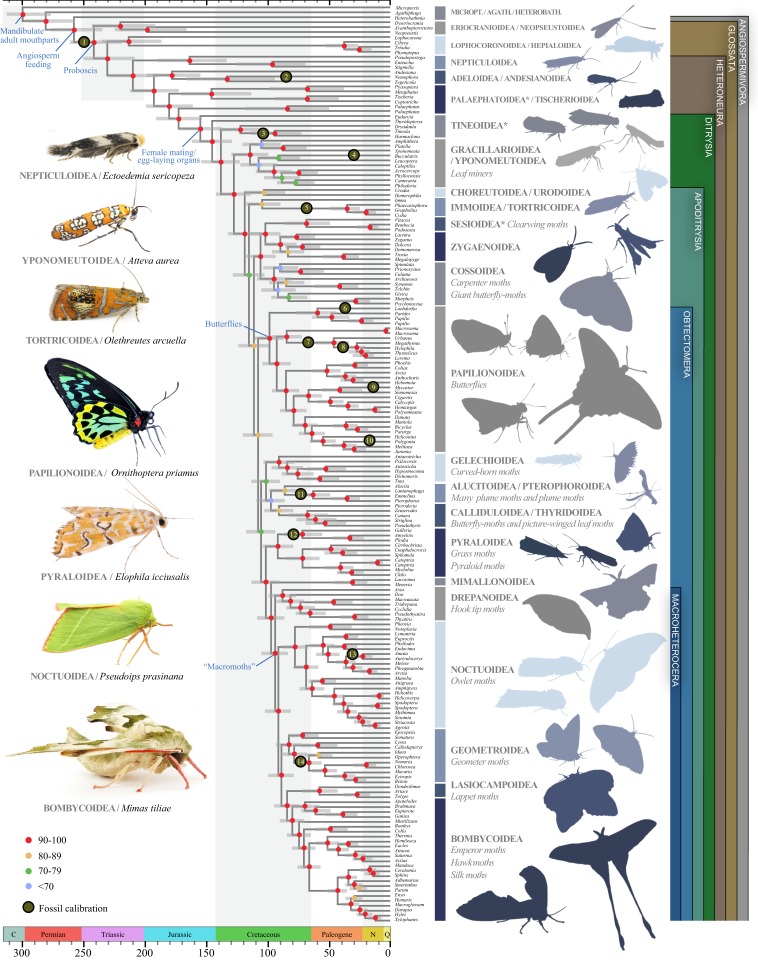

Fig. 1.

Dated evolutionary tree of butterfly and moth relationships. The tree is derived from a maximum-likelihood analysis of 749,791 amino acid sites. Branch lengths and node ages are computed in a time-calibrated analysis of 198,050 amino acid sites and 16 fossil calibrations. Gray bars depict 95% credibility intervals of node ages. Asterisks indicate superfamilies that are nonmonophyletic in the tree. The color-coding of nodes indicates nonparametric bootstrap support values. Two of the 16 fossils were placed on outgroup branches; their placements are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S4. Scale bar is in millions of years. MICROPT, Micropterigoidea; AGATH, Agathiphagoidea; HETEROBATH, Heterobathmioidea. Additional information on fossil calibrations is provided in Dataset S10 and SI Appendix, Supplementary Archive 8.

Phylogenetic analyses, regardless of dataset or analysis type, recovered the monophyly of Lepidoptera and many other previously hypothesized clades within the order, including Angiospermivora, Glossata, and Ditrysia, with strong branch support (Dataset S5). Our results indicate that the most recent common ancestor of crown Lepidoptera appeared in the Late Carboniferous, ∼299.5 Ma (95% credibility interval [CI], 312.4 to 276.4 Ma; Fig. 1), significantly predating the oldest known lepidopteran fossil from the Triassic-Jurassic boundary (201 Ma; Dataset S10). Among Lepidoptera, the superfamilies Micropterigoidea, Agathiphagoidea, and Heterobathmioidea have been considered “primitive moths,” because their adults have functional mandibulate mouthparts and other plesiomorphic features, including feeding on nonvascular land plants (19). Prior molecular studies suggested that Agathiphagoidea, which are seed borers on the ancient conifer family Araucariaceae (19, 20), is the sister group to either Micropterigoidea (12, 21) or Heterobathmioidea (22). Our study contradicts these findings, confidently placing Micropterigoidea, which are detritivores or bryophyte feeders (7), as the sister group to all other Lepidoptera (280.6 Ma; CI, 297.0 to 257.4 Ma), with Agathiphagoidea as the closest relative to all remaining lineages, corroborating traditional morphology-based studies (19). Our results imply that the ancestral mandibulate moth may have been feeding on bryophytes ∼300 Ma, followed by some lineages transitioning to vascular plants and then to angiosperms, largely following the evolutionary history of plants.

Angiospermivora, which feed predominantly on flowering plants as larvae (21), are composed of the mandibulate Heterobathmioidea and all proboscis-bearing Lepidoptera. The crown age of Angiospermivora is dated at 257.7 Ma (CI, 276.7 to 234.5 Ma), and our analyses unequivocally inferred Heterobathmioidea as a sister group to all other taxa within this clade. Both groups have leaf-mining larvae (19), suggesting that moths were internal plant tissue feeders in the Late Permian. Although the crown age of flowering plants remains controversial (23), there is general agreement that some angiosperm lineages, which are in part now extinct, were present >300 Ma (24), a consensus corroborated by a long stem branch that links angiosperms to gymnosperms in recent studies (24–29). Our results support the hypothesis that Lepidoptera were internal feeders before becoming predominantly external herbivores (1, 3, 7, 19). Large body size, a characteristic of some extant butterflies and moths, may be an ecological consequence of being freed from the constraints of living within plants (7), thereby allowing greater access to nectar sources and the ability to fly far distances.

The adult proboscis is the unifying feature of clade Glossata, which contains >99% of all extant Lepidoptera species (2). The proboscis is considered an important innovation that enabled lepidopteran diversification (19). Adults of Heterobathmioidea, the sister group to Glossata, use their mandibles to eat pollen of the ancient Nothofagus tree (19). Adults of Eriocranioidea, part of a 3-family clade sister to all other Glossata, use their proboscis to drink water or sap (19), a behavior that may have been the precursor to nectar feeding. The common ancestor of nectar-feeding Lepidoptera first appeared in the Middle Triassic (241.4 Ma; CI, 261.1 to 218.9 Ma), overlapping with the estimated diversification periods of speciose flowering plant crown groups (Fig. 2).

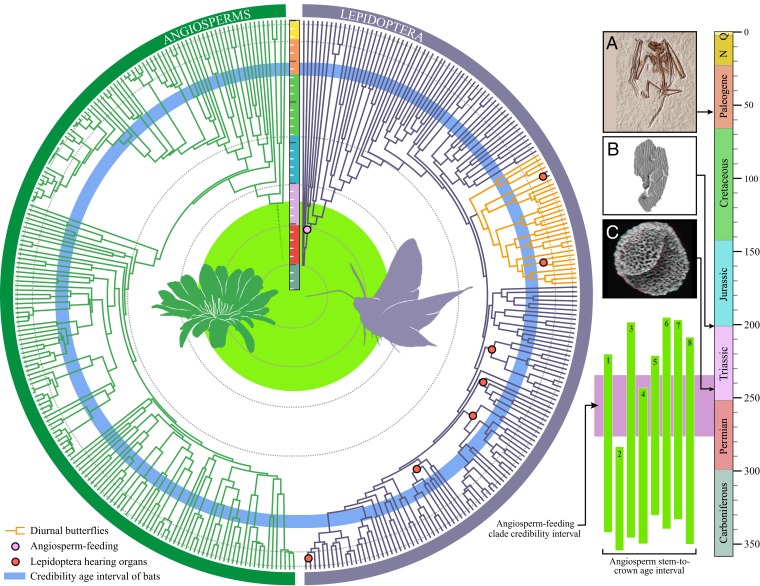

Fig. 2.

Correlations among evolution of lepidopteran traits, angiosperms, and bats. Dated lepidopteran tree from Fig. 1 (right half of circle, purple tree); recent dated angiosperm phylogeny from ref. 27 (left half of circle, green tree). The blue ring represents the credibility interval for the age of bats (30). Red nodes represent independent origins of ancestral Lepidoptera with hearing organs; 4 additional origins are not shown on this tree because they are represented by terminal lineages and could not be assigned to a node (SI Appendix, Fig. S33). Diurnal butterfly lineages are shown as orange branches. The large light green circle in the middle of the tree corresponds to bar 5 in the rectangular box on the right. The 8 green vertical bars in this rectangular box represent stem-to-crown intervals for the age of angiosperms based on recent evolutionary studies (Dataset S12). Tick marks on vertical scale bars represent 10-Ma intervals. Images are of the oldest known echolocating bat fossil, Icaronycteris index (A), Lepidoptera scale (B), and angiosperm pollen (C). Fig. 2A is reprinted with permission of the Royal Ontario Museum, © ROM. Fig. 2B is reprinted from ref. 66; © The Authors of ref. 66, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of Science. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial License 4.0 (CC BY-NC). Fig. 2C is reprinted with permission from ref. 69, which is licensed under CC BY 3.0. Full accreditation and additional acknowledgments are provided in SI Appendix.

The clade Ditrysia, which is estimated to have a late-Jurassic crown age (154.7 Ma; CI, 172.1 to 137.5 Ma) is the most taxonomically and ecologically diverse group of Lepidoptera, with >150,000 described species. Ditrysia includes butterflies and many moth superfamilies that predominantly feed on angiosperms as larvae. Monophyly of Ditrysia, recovered in all of our molecular analyses, is supported by a unique apomorphy: females have 2 reproductive openings, 1 for mating and another for egg-laying (17, 19). Relationships among major ditrysian groups such as Apoditrysia, sensu Regier et al. (12) and Mutanen et al. (22), uniting butterflies and many diverse moth families, are statistically well supported (Dataset S5). Most Apoditrysia have additional sensilla on the proboscis (19), implying that further specialization on adult food resources may have arisen in the Early Cretaceous (118.5 Ma; CI, 132.1 to 105.6 Ma).

Butterflies (Papilionoidea) are some of the most popular arthropods, and include nearly 19,000 described species (3). One of the major challenges thus far has been to confidently place butterflies within Lepidoptera (12, 17, 21, 30). We identified Papilionoidea as the sister group to all remaining Obtectomera (including silk moths, owlet moths, grass moths, and others; Fig. 1) with strong nodal support and statistical evidence from topology tests that rule out the impact of confounding signal (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). This result confidently shows that butterflies are diurnal moths with a Late Cretaceous crown age (98.3 Ma; CI, 110.3 to 86.9 Ma), slightly younger than other published estimates using butterfly fossils and host-plant maximum age calibrations (13, 31–34). Swallowtails (Papilionoidea) were the sister group to the remaining butterfly families; skippers (Hesperiidae) and neotropical nocturnal moth-like butterflies (Hedylidae) were sister groups (84.4 Ma; CI, 96.6 to 72.2 Ma). Whites and sulfurs (Pieridae; 51.7 Ma; CI, 63.9 to 40.4 Ma) formed a clade that was the sister group to the clade containing the hairstreaks, blues, metalmarks (Lycaenidae + Riodinidae; 66.6 Ma; CI, 77.7 to 55.7 Ma), and brushfoot butterflies (Nymphalidae; 69.4 Ma; CI, 80.2 to 59.0 Ma).

Butterflies were hypothesized to have become diurnal because of selective pressure from predatory bats (35, 36). Phylogenetic studies that used molecular and morphological data independently confirmed the crown age of bats to be 55–65 Ma (37–41) and the crown age of the bat clade with laryngeal echolocation to be ∼50 Ma (10, 40, 42, 43). Nocturnality in Lepidoptera dates back to at least the ancestor of Heteroneura, in the Jurassic (209.7 Ma; CI, 249.9 to 208.1 Ma) (SI Appendix, Fig. S34 and Dataset S11), and the switch to diurnality occurred multiple times, but most notably in the ancestor of Papilionoidea (98.3 Ma; CI, 110.3 to 86.9 Ma). Thus, diurnal activity in butterflies likely cannot be attributed to bat predation but may be due to another factor, such as nectar availability during the day. Bees, whose crown age is estimated as 125 to 100 Ma (44), may have driven angiosperm flower color evolution (36), and butterflies followed by becoming diurnal opportunists of these nectar resources.

The extraordinary diversity of ultrasonic hearing organs in nocturnal moths is thought to have evolved in response to the diversification of the echolocating-bat crown group in the Early Paleogene (11). We identified 9 different origins of hearing organs in nocturnal moth clades (SI Appendix, Figs. S33 and S34), more than previously hypothesized (11). Four of these are species-rich clades (Drepanoidea, Geometroidea, Noctuoidea, and Pyraloidea), in which ears appear to have arisen in the Late Cretaceous (median age range of crown nodes, 91.6 to 77.6 Ma; CI, 103.4 to 67 Ma; Fig. 2), millions of years before echolocating bats. Our results imply that moth hearing organs might not have arisen in response to bat predation but likely evolved in response to a different selective pressure. Many moths produce sounds for sexual communication (9), but the most likely explanation for the evolution of hearing organs in Lepidoptera, and animals more broadly, is general auditory surveillance of the environment for broadband sounds produced by animal movement (e.g., predators) (45). Behavioral and neural evidence has shown that moths respond to the low-frequency (<20 kHz) walking and wingbeat sounds of predatory birds (46, 47). Day-flying Lepidoptera and moths endemic to bat-free islands show reduced auditory sensitivity to higher frequencies yet retain reactive thresholds at lower frequencies, comparable to the thresholds of other nocturnal moth species (10). Therefore, hearing organs likely evolved first for auditory surveillance before subsequently being co-opted for bat detection.

In summary, our study reveals that the common ancestor of the butterflies and moths we observe today was likely a small, Late Carboniferous species with mandibulate adults and with larvae that fed internally on nonvascular land plants. Our dating analyses with different fossils and models confirm the hypothesis that the majority of Lepidoptera proliferated with the rise of angiosperms in the Cretaceous. Hearing organs in nocturnal Lepidoptera originated several times separately, before the rise of echolocating bats. Butterflies similarly became diurnal before diversification of the bat crown group, contrary to the hypothesis that butterflies became day-fliers to escape these predators. Instead, butterflies likely became diurnal to capitalize on day-blooming flowers. Our study provides a robust phylogenetic framework and reliable time estimates for future studies on the ecology and evolution of one of the most prominent insect lineages. Data and results from this study will serve as a foundation for future comparative analyses on butterflies and moths.

Materials and Methods

Phylogenomic Analyses.

Transcriptome and genome sequences from 186 species of Lepidoptera were used for our study, along with sequences of 17 outgroup species representing other holometabolous insect orders, totaling 203 species (Dataset S1). Transcriptomes from 69 of these species were newly sequenced by either the 1K Insect Transcriptome Evolution (1KITE) consortium or by the Kawahara Lab, Florida Museum of Natural History (FLMNH). RNA extractions, mRNA isolation, fragmentation, cDNA library construction, and transcriptome sequencing were performed using the protocols of Misof et al. (48) and Peters et al. (44) for the 1KITE consortium samples. Protocols of Kawahara and Breinholt (16) were used for the FLMNH samples (SI Appendix, section 2).

Transcriptome assembly and contaminant removal protocols largely followed Peters et al. (44) and Kawahara and Breinholt (16); additional information on these methods is available in SI Appendix, sections 3 and 4. An ortholog set was compiled based on the OrthoDB v7 database (49), using 2 ingroups (Bombyx mori and Danaus plexippus) and 1 outgroup (Tribolium castaneum) as reference species. The assemblies were searched for transcripts of 3,429 single-copy protein coding genes using Orthograph beta4 (50). Orthograph identified a total of 3,427 of the 3,429 orthologs across all included taxa. Amino acid sequences of each ortholog were aligned in MAFFT v7.294 (51) and refined using the protocols of Misof et al. (48). Corresponding nucleotide alignments were generated using a modified version of Pal2Nal v14 (52) with amino acid alignments as blueprints. Supermatrices for the amino acid and nucleotide datasets were generated using FasConCat-G v1.0 (53), and synonymous signal was removed from the nucleotide dataset using Degen v1.4 (54). Additional information on generation of the ortholog set and the final amino acid and “degen1” nucleotide datasets is available in SI Appendix, sections 5 and 6. PartitionFinder2 v2.1.1 (55) and RAxML v8.2.11 (56) were used to obtain the optimal partitioning scheme for the concatenated amino acid dataset; the boundaries of the merged partitions in this scheme were adjusted at the nucleotide level and used for the concatenated degen1 nucleotide dataset. The best-fitting models were reestimated using ModelFinder in IQ-TREE v1.5.5 (57, 58) for both datasets, and maximum likelihood (ML) tree inferences were subsequently conducted. A minimum of 50 ML tree searches were performed for each dataset using IQ-TREE v1.5.5 (57); the tree with the best log-likelihood was selected as the best tree for each analysis. Multiple metrics of statistical support, including nonparametric bootstrap replicates, SH-aLRT (59), and TBE support values (60), were generated to assess the reliability of the best ML tree in each analysis. Multispecies coalescent analyses were also performed on the amino acid dataset in ASTRAL-III v5.6.3 (61), using 2 sets of individual gene trees that had been inferred with IQ-TREE v1.6.10 (57): a set of the best ML trees for each gene (inferred from 25 ML tree searches per locus) and a set of the consensus trees for each gene partition, with each consensus tree generated using 1,000 ultrafast bootstrap (UFBoot2) replicates (62).

The placement of 3 selected Lepidoptera clades (Alucitidae + Pterophoridae, Bombycoidea, and Papilionoidea) was further assessed using FcLM in IQ-TREE v1.6.7 (57), with predefined groups of taxa, to check for hidden signal and bias due to nonrandomly distributed missing data and (among-lineage) compositional heterogeneity, following the protocol of Misof et al. (48). Additional information on data partitioning, model selection, topology tests, tree inference using the partitioned supermatrix and the multispecies coalescent approach, and branch support is available in SI Appendix, sections 7 and 8.

Divergence Time Estimation.

Divergence time estimations were computed on truncated datasets to allow completion of the analyses. AliStat v1.6 (63) was used to generate a subsampled dataset containing 195 Amphiesmenoptera species (all non-Amphiesmenoptera removed) and only including sites for which at least 80% of samples had unambiguous amino acids. MCMCTree and codeml (both part of the PAML software package, v4.9g) (64) were used to estimate divergence dates on this subsampled dataset. The best ML tree inferred from the concatenated amino acid dataset was used as the input tree. The input tree was first calibrated using age estimates of 16 carefully selected fossils, following the best-practice recommendations by Parham et al. (65). Although all 16 fossils have diagnostic morphological characteristics that enable reasonably confident placement on the tree, only 3 of these fossils have true synapomorphies. To strictly follow the guidelines of Parham et al. (65), additional analyses were performed using only these 3 fossils. We applied a conservative age constraint on the root of the input tree, with a minimum age of 201 Ma, based on the stem Glossata scale fossils discovered by van Eldijk et al. (66) and a maximum age of 314.4 Ma, based on the absence of Amphiesmenoptera fossils in the Late Carboniferous. We used 2 well-established approaches to convert fossil ages into calibrations on tree nodes. For the conservative strategy, fossil calibrations were treated with uniform distributions constrained between the corresponding fossil age (the minimum bound) and a hard maximum equal to the maximum root age. For the second strategy, the truncated-Cauchy distribution (67) was used to set calibrations for internal nodes younger than 80 Ma. (Additional information on this approach is provided in SI Appendix, section 10.) We applied both uncorrelated rates and autocorrelated rates to estimate divergence, for a total of 8 analyses: 2 sets of fossil calibrations (16 fossils and 3 fossils) × 2 fossil calibration strategies (uniform and Cauchy priors for nodes <80 Ma) × 2 rate types (independent and autocorrelated). To compare the radiation of Lepidoptera and flowering plants, estimates of the mean age of the ancestral angiosperm were compiled from the literature; these angiosperm ages are presented in Dataset S12 and shown in Fig. 2. Since the estimated timespan between divergence of angiosperms and gymnosperms is large, and it is possible that flowering plants existed long before the crown of angiosperms, we present the interval between the mean age of the crown (node Angiosperm) and the mean age of the stem (node Angiosperm + Gymnosperm) from the abovementioned studies (Dataset S12). Additional information and justification for our approaches to divergence time estimation is available in SI Appendix, section 10.

Ancestral State Reconstruction.

We conducted ancestral state reconstruction on ultrasonic hearing organs and adult diel activity. All ancestral state reconstruction analyses were performed on the best tree from the ML analysis of the concatenated amino acid dataset (SI Appendix, Figs. S33 and S34), using stochastic character mapping, with the “make.simmap” command in the R package Phytools v06-44 (68). Ten thousand stochastic maps were generated for each analysis. The presence of a hearing organ was treated as a binary character in one ASR analysis and as a 7-state character in a separate ASR analysis that accounts for variation in the location of the hearing organ (see matrices A and B in Dataset S13). Diel activity was treated as a 4-state character (Dataset S14). Additional information on ancestral state reconstruction and how characters were coded is provided in SI Appendix, section 11.

Data Availability.

Additional data are provided in Supplementary Archives on DRYAD (70).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Data presented here are the result of the collaborative efforts of the 1KITE consortium (https://www.1kite.org/). Sequencing and assembly of 1KITE transcriptomes were funded by BGI through support to the China National GeneBank. This project was also financially supported by multiple grants from the NSF and the German Research Foundation; a list of grant numbers and additional acknowledgements are provided in SI Appendix.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Transcriptome assemblies for the newly sequenced transcriptomes used in this study either have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly archive (all accession nos. provided in Dataset S1) or in a DRYAD digital repository (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.j477b40, Supplementary Archive 1). Other data files have also been archived in the same DRYAD repository. The contents of these archives are listed in the SI Appendix.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1907847116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Grimaldi D., Engel M. S., Evolution of the Insects (Cambridge Univ Press, Cambridge, UK, 2005), p. 772. [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Nieukerken E. J., et al. , “Order Lepidoptera Linnaeus, 1758” in Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-Level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness, Zhang Z.-Q., Ed. (Magnolia Press, Auckland, New Zealand, 2011), vol. 3148, pp. 212–221. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitter C., Davis D. R., Cummings M. P., Phylogeny and evolution of Lepidoptera. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 62, 265–283 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ehrlich P. R., Raven P. H., Butterflies and plants: A study in coevolution. Evolution 18, 586–608 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiegmann B. M., et al. , Nuclear genes resolve Mesozoic-aged divergences in the insect order Lepidoptera. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 15, 242–259 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bazinet A. L., et al. , Phylotranscriptomics resolves ancient divergences in the Lepidoptera. Syst. Entomol. 42, 305–316 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell J. A., Mitter C., Farrell B. D., “Evolution of larval food preferences in Lepidoptera” in Handbook of Zoology, Kristensen N. P., Ed. (Volume IV, Arthropoda: Insecta, Part 35. Lepidoptera, Moths and Butterflies, Volume 1: Evolution, Systematics, and Biogeography, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York, 1998), pp. 403–422. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawahara A. Y., et al. , Diel behavior in moths and butterflies: A synthesis of data illuminates the evolution of temporal activity. Org. Divers. Evol. 18, 13–27 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conner W. E., Corcoran A. J., Sound strategies: The 65-million-year-old battle between bats and insects. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 57, 21–39 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ter Hofstede H. M., Ratcliffe J. M., Evolutionary escalation: The bat-moth arms race. J. Exp. Biol. 219, 1589–1602 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kristensen N. P., Molecular phylogenies, morphological homologies and the evolution of “moth ears”. Syst. Entomol. 37, 237–239 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Regier J. C., et al. , A large-scale, higher-level, molecular phylogenetic study of the insect order Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies). PLoS One 8, e58568 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wahlberg N., Wheat C. W., Peña C., Timing and patterns in the taxonomic diversification of Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths). PLoS One 8, e80875 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heikkilä M., Mutanen M., Wahlberg N., Sihvonen P., Kaila L., Elusive ditrysian phylogeny: An account of combining systematized morphology with molecular data (Lepidoptera). BMC Evol. Biol. 15, 260 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bazinet A. L., Cummings M. P., Mitter K. T., Mitter C. W., Can RNA-Seq resolve the rapid radiation of advanced moths and butterflies (Hexapoda: Lepidoptera: Apoditrysia)? An exploratory study. PLoS One 8, e82615 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawahara A. Y., Breinholt J. W., Phylogenomics provides strong evidence for relationships of butterflies and moths. Proc. Biol. Sci. 281, 20140970 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breinholt J. W., et al. , Resolving relationships among the megadiverse butterflies and moths with a novel pipeline for anchored phylogenomics. Syst. Biol. 67, 78–93 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strimmer K., von Haeseler A., Likelihood-mapping: A simple method to visualize phylogenetic content of a sequence alignment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 6815–6819 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kristensen N. P., Handbook of Zoology, Kristensen N. P., Ed. (Volume IV, Arthropoda: Insecta, Part 35. Lepidoptera, Moths and Butterflies, Volume 1: Evolution, Systematics, and Biogeography, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leslie A. B., et al. , Hemisphere-scale differences in conifer evolutionary dynamics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16217–16221 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Regier J. C., et al. , A molecular phylogeny and revised classification for the oldest ditrysian moth lineages (Lepidoptera: Tineoidea), with implications for ancestral feeding habits of the mega‐diverse Ditrysia. Syst. Entomol. 40, 409–432 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mutanen M., Wahlberg N., Kaila L., Comprehensive gene and taxon coverage elucidates radiation patterns in moths and butterflies. Proc. Biol. Sci. 277, 2839–2848 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beaulieu J. M., O’Meara B. C., Crane P., Donoghue M. J., Heterogeneous rates of molecular evolution and diversification could explain the Triassic age estimate for angiosperms. Syst. Biol. 64, 869–878 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sauquet H., Magallón S., Key questions and challenges in angiosperm macroevolution. New Phytol. 219, 1170–1187 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li H.-T., et al. , Origin of angiosperms and the puzzle of the Jurassic gap. Nat. Plants 5, 461–470 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salomo K., et al. , The emergence of earliest angiosperms may be earlier than fossil evidence indicates. Syst. Bot. 42, 607–619 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster C. S. P., et al. , Evaluating the impact of genomic data and priors on Bayesian estimates of the angiosperm evolutionary timescale. Syst. Biol. 66, 338–351 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Foster C. S. P., Ho S. Y. W., Strategies for partitioning clock models in phylogenomic dating: Application to the angiosperm evolutionary timescale. Genome Biol. Evol. 9, 2752–2763 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barba-Montoya J., Dos Reis M., Schneider H., Donoghue P. C. J., Yang Z., Constraining uncertainty in the timescale of angiosperm evolution and the veracity of a Cretaceous Terrestrial Revolution. New Phytol. 218, 819–834 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Regier J. C., et al. , Toward reconstructing the evolution of advanced moths and butterflies (Lepidoptera: Ditrysia): An initial molecular study. BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 280 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Espeland M., et al. , A comprehensive and dated phylogenomic analysis of butterflies. Curr. Biol. 28, 770–778.e5 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wahlberg N., et al. , Nymphalid butterflies diversify following near demise at the Cretaceous/Tertiary boundary. Proc. Biol. Sci. 276, 4295–4302 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Heikkilä M., Kaila L., Mutanen M., Peña C., Wahlberg N., Cretaceous origin and repeated tertiary diversification of the redefined butterflies. Proc. Biol. Sci. 279, 1093–1099 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chazot N., et al. , Priors and posteriors in Bayesian timing of divergence analyses: The age of butterflies revisited. Syst. Biol. 68, 797–813 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yack J. E., Fullard J. H., Ultrasonic hearing in nocturnal butterflies. Nature 403, 265–266 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fullard J. H., “Sensory coevolution of moths and bats” in Comparative Hearing: Insects, Hoy R. R., Popper A. N., FayIn R. R., Eds. (Springer, New York, 1998), pp. 279–326. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Upham N., Esselstyn J. A., Jetz W., Ecological causes of uneven diversification and richness in the mammal tree of life. bioRxiv:10.1101/504803 (posted March 28, 2019).

- 38.dos Reis M., et al. , Phylogenomic datasets provide both precision and accuracy in estimating the timescale of placental mammal phylogeny. Proc. Biol. Sci. 279, 3491–3500 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shi J. J., Rabosky D. L., Speciation dynamics during the global radiation of extant bats. Evolution 69, 1528–1545 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Teeling E. C., Hear, hear: The convergent evolution of echolocation in bats? Trends Ecol. Evol. 24, 351–354 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agnarsson I., Zambrana-Torrelio C. M., Flores-Saldana N. P., May-Collado L. J., A time-calibrated species-level phylogeny of bats (Chiroptera, Mammalia). PLoS Curr. 3, RRN1212 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Veselka N., et al. , A bony connection signals laryngeal echolocation in bats. Nature 463, 939–942 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simmons N. B., Seymour K. L., Habersetzer J., Gunnell G. F., Primitive Early Eocene bat from Wyoming and the evolution of flight and echolocation. Nature 451, 818–821 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peters R. S., et al. , Evolutionary history of the Hymenoptera. Curr. Biol. 27, 1013–1018 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mikhail A., Lewis J. E., Yack J. E., What does a butterfly hear? Physiological characterization of auditory afferents in Morpho peleides (Nymphalidae). J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 204, 791–799 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacobs D. S., Ratcliffe J. M., Fullard J. H., Beware of bats, beware of birds: The auditory responses of eared moths to bat and bird predation. Behav. Ecol. 19, 1333–1342 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fournier J. P., Dawson J. W., Mikhail A., Yack J. E., If a bird flies in the forest, does an insect hear it? Biol. Lett. 9, 20130319 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Misof B., et al. , Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science 346, 763–767 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waterhouse R. M., Tegenfeldt F., Li J., Zdobnov E. M., Kriventseva E. V., OrthoDB: A hierarchical catalog of animal, fungal and bacterial orthologs. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D358–D365 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Petersen M., et al. , Orthograph: A versatile tool for mapping coding nucleotide sequences to clusters of orthologous genes. BMC Bioinformatics 18, 111 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katoh K., Standley D. M., MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Suyama M., Torrents D., Bork P., PAL2NAL: Robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, W609–W612 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kück P., Longo G. C., FASconCAT-G: Extensive functions for multiple sequence alignment preparations concerning phylogenetic studies. Front. Zool. 11, 81 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zwick A., Regier J. C., Zwickl D. J., Resolving discrepancy between nucleotides and amino acids in deep-level arthropod phylogenomics: Differentiating serine codons in 21-amino-acid models. PLoS One 7, e47450 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lanfear R., Frandsen P. B., Wright A. M., Senfeld T., Calcott B., PartitionFinder 2: New methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 772–773 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stamatakis A., RAxML version 8: A tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30, 1312–1313 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nguyen L. T., Schmidt H. A., von Haeseler A., Minh B. Q., IQ-TREE: A fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chernomor O., von Haeseler A., Minh B. Q., Terrace aware data structure for phylogenomic inference from supermatrices. Syst. Biol. 65, 997–1008 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guindon S., et al. , New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: Assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lemoine F., et al. , Renewing Felsenstein’s phylogenetic bootstrap in the era of big data. Nature 556, 452–456 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang C., Rabiee M., Sayyari E., Mirarab S., ASTRAL-III: Polynomial time species tree reconstruction from partially resolved gene trees. BMC Bioinformatics 19 (suppl. 6), 153 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hoang D. T., Chernomor O., von Haeseler A., Minh B. Q., Vinh L. S., UFBoot2: Improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 518–522 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wong T. K. F., et al. , CSIRO software collection (AliStat version 1.3, CSIRO, Canberra, Australia, 2014).

- 64.Yang Z., PAML 4: Phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Parham J. F., et al. , Best practices for justifying fossil calibrations. Syst. Biol. 61, 346–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.van Eldijk T. J. B., et al. , A Triassic-Jurassic window into the evolution of Lepidoptera. Sci. Adv. 4, e1701568 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Inoue J., Donoghue P. C. J., Yang Z., The impact of the representation of fossil calibrations on Bayesian estimation of species divergence times. Syst. Biol. 59, 74–89 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Revell L. J., Phytools: An R package for phylogenetic comparative biology (and other things). Methods Ecol. Evol. 3, 217–223 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hochuli P. A., Feist-Burkhardt S., Angiosperm-like pollen and Afropollis from the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of the Germanic Basin (Northern Switzerland). Frontiers Plant Sci. 4, 1–14 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kawahara A. Y., et al. , Phylogenomics reveals the evolutionary timing and pattern of butterflies and moths. Dryad. 10.5061/dryad.j477b40. Deposited 18 September 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Additional data are provided in Supplementary Archives on DRYAD (70).