Abstract

Objective

Not all depressive individuals are suicidal. An increasing body of studies has examined forgiveness, especially self-forgiveness, as a protective factor of suicide based on that suicide is often accompanied by negative self-perceptions. However, less has been studied on how different subtypes of forgiveness (i.e., forgiveness-of-self, forgiveness-of-others and forgiveness-of-situations) could alleviate the effects of depression on suicide. Hence, this study examined forgiveness as a moderator of depression and suicidality.

Methods

305 participants, consisted of 87 males and 218 females, were included in the study. The mean age was 41.05 (SD: 14.48; range: 19–80). Depression, anxiety, and forgiveness were measured through self-report questionnaires, and suicidal risk was measured through a structuralized interview. Moderations were examined through hierarchical regression analyses.

Results

Depression positively correlated with suicidality. Results of the hierarchical regression analysis indicated forgiveness as a moderator of depression on suicidality. Further analysis indicated only forgiveness-of-self as a significant moderator; the effects of forgiveness-of-others and forgiveness-of-situation were not significant.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that forgiveness-of-self is essential in reducing of the effects of depression on suicidality. It is suggested that self-acceptance and the promotion of self-forgiveness should be considered as an important factor when developing suicide prevention strategies.

Keywords: Depression, Suicidality, Forgiveness-of-self, Forgiveness-of-others, Forgiveness-of-situation

INTRODUCTION

Depression is a robust predictor of suicidal behaviors [1-3]. However, the fact that not all depressed individuals are suicidal [4-6] substantiates the need to examine individual differences that contribute to the development of suicidal behaviors in depressed individuals.

Recently, resilience factors and their role in promoting mental health has gained much attention [7-9]. In particular, numerous studies have examined the effects of forgiveness on mental health issues including suicide [6,10-15]. While literature suggests that dispositional forgiveness can be distinguished into forgiveness-of-self, forgiveness-of-others, and forgiveness-of-situations [16,17], forgiveness-of-self has been of most interest because suicide is often perceived as self-directed aggression, and multiple theories suggest that suicide is often accompanied by negative self-images [18-20]. The basic assumption is that if suicidal behaviors contain an aspect of impaired self-image, then its intensity and frequency ought to reduce in those who display high levels of self-forgiveness and are more accepting of the self.

According to a recent review, 13 out of 14 studies, which have examined the direct effect of forgiveness on suicidal behaviors, reported a significant association between the two constructs [15]. Sansone et al. [14] claimed that those with a history of suicide attempt were not only less likely to forgive themselves and others but were also less likely to believe in forgiveness by others. Furthermore, studies have consistently reported indirect effects of forgiveness on suicide. Liu et al. [13] found significant moderating effects of forgiveness in the path between victimization (i.e., bullying) and suicide ideation. A series of studies examining the effects of forgiveness-of-self, forgiveness-of-others and forgiveness-by-God on suicide reported that self-forgiveness was mediated by depression to predict suicidal behaviors, whereas forgiveness-of-others had a direct effect. A follow up from the same study group reported that self-forgiveness moderated the effects of inward and outward anger on suicide [11,12].

Despite the increase of studies that examined the direct and the indirect effects of forgiveness on suicidal behaviors, no study has reported how discrete types of forgiveness can regulate the effects of depression on suicide. Although Hirsch et al. [11] did identify depression as a mediator between self-forgiveness and suicidal behaviors, it seems more adequate to examine the significance of forgiveness as a moderator of depression and suicide considering (a) the constant association between depression and suicide [1], and (b) the effects of forgiveness in reducing suicidal behaviors [15]. In short, levels of forgiveness might act as individual differences that protect depressive individuals from engaging in suicidal behaviors, and it is anticipated that examining forgiveness as a protective factor of suicide will provide noteworthy implications for its prevention.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to examine the role of forgiveness between depression and suicidal behaviors. More specifically, we aimed to inspect whether forgiveness could attenuate the effects of depression on suicide. We hypothesized that forgiveness would significantly moderate the path between depression and suicidal behaviors. Among the three types of dispositional forgiveness (i.e., forgiveness-of-self, forgiveness-of-others, forgiveness-of-situation), we hypothesized that self-forgiveness would be a significant moderator based on previous literature that suggested disturbed self-image as a crucial factor of suicide.

METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited from the local community. Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I) 5.0 was administered to identify the presence of psychiatric disorders. 314 participants were enrolled, however, 9 (2.87%) were excluded because they failed to complete the entire questionnaire. The final analyses included 305 (97.13%) participants of whom 87 were male (28.5%) and 218 were female (71.5%). The mean age was 41.05 years (SD=14.48; range: 19–80 years), and the mean years of education was 14.43 (SD=4.06; range: 0–24 years). The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ilsan Paik Hospital (IRB: ISPAIK 2015-05-221-009), and all participants provided a written informed consent prior to their participation.

Measures

Korean version of the Beck depression inventory-II (K-BDI-II)

The official Korean version of the BDI-II [21] was applied in order to measure levels of depression. The K-BDI-II is an adapted version of the Beck Depression Inventory-II, which is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that was developed to evaluate the severity of depressive symptoms within a two-week period [22]. In this study, we excluded item 9, which measures suicidal thoughts, from the total score to avoid confounding depression with suicidality. The 20 items of the BDI-II demonstrated high internal consistency (α=0.95).

Korean version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (K-BAI)

The official Korean version of the BAI [21] was utilized to measure levels of anxiety. The K-BAI is an adapted version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory, which is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that was developed to evaluate the severity of anxiety within a one-week period [23]. Each item is rated on a fourpoint Likert scale. The total score can range from 0 to 63 with higher scores indicating more severe levels of anxiety. In the present study, the 21-item questionnaire demonstrated high internal consistency (α=0.97).

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

Suicidality was measured through the Korean version of the M.I.N.I. The M.I.N.I. was initially developed by Sheehan et al. [24] and the Korean version was validated by Yoo et al. [25] The suicidality module of the M.I.N.I. is consisted of six yesor-no questions. The questions ask for current suicide risk (i.e., passive and active suicide ideation, desire for self-harm, suicide planning, and suicide attempt within a one-month period) and lifetime history of suicide attempts. The questions are asked in an ascending order of severity, and the final score is the score of the last endorsed item. Final scores from 1 to 5 indicate low levels of suicidality; 6 to 9 indicate intermediate levels of suicidality; 10 or higher indicates high levels of suicidality.

Korean version of the Heartland Forgiveness Scale

The Korean version of the Heartland Forgiveness Scale (K-HFS) was applied to measure levels of forgiveness [26]. The K-HFS is an adapted version of the Heartland Forgiveness Scale, which was originally developed by Thompson et al. [17] It consists of three sub-constructs (i.e., forgiveness-of-self, forgiveness-of-others, and forgiveness-of-situation), which are composed of six items each. Each item is evaluated on a 7-point Likert scale and higher scores indicate greater degrees of forgiveness. Hong et al. [26] reported high internal consistency for the K-HFS (α=0.80). In this study, the 18-items revealed excellent internal consistency (α=0.89). In addition, the six items for forgiveness-of-self (α=0.77), the six items for forgiveness-of-others (α=0.74,) and the six items for forgiveness-of-situation (α=0.78) demonstrated adequate reliability.

Data analyses

Data analyses were conducted through SPSS 21.0 and SPSS Macro PROCESS for SPSS 2.16.3 [27]. Pearson’s correlation analysis with bootstrapping at a 5,000-sampling rate was performed to examine the correlations among the variables. Bootstrapping was initially applied to prevent multiple comparison issues that can occur when simultaneously examining correlations among a large number of variables [28,29]. Following the correlation analysis, a hierarchical regression analysis was performed to examine the interaction between depression and forgiveness on suicidality. Gender and anxiety, which have been associated with suicidal behaviors [30-32], were entered in the first stage to be controlled for. The second stage included depression and forgiveness, and the third stage included the two-way interaction between depression and forgiveness (i.e., depression×forgiveness).

Next, an additional hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to verify which forgiveness configuration (i.e., forgiveness-of-self, forgiveness-of-others, and forgiveness-of-situation) would significantly moderate the path between depression and suicidality. Once again, gender and anxiety were controlled for as they were entered in the first stage. The second stage included depression, forgiveness-of-self, forgiveness-ofothers, and-forgiveness-of-situation. In the third stage, the three two-way interactions between depression and specific forgiveness subtypes were entered (i.e., depression×forgiveness-ofself; depression×forgiveness-of-others; depression×forgivenessof-situation). All predicting variables were mean centered to prevent multicollinearity.

Finally, the Johnson-Neyman technique [33,34] was applied to investigate the regions in which the moderating variable had significant effect. The Johnson-Neyman technique aligns the moderating variable in a continuous manner and computes the regions of significance for interactions by examining the significance between the predictor and outcome variables [35-37]. If the confidence intervals contain the value zero, it implies an insignificant conditional indirect effect and a significant moderating effect. On the other hand, confidence intervals that do not include the value zero indicate that the conditional indirect effect is significant and the moderating effect is not [4]. All significance levels were set at p<0.05 (two-tailed).

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics

Demographic information as well as the basic information regarding the psychological measures are presented in Table 1. Among the 305 participants, 40 (13.1%) responded positive to having a current depressive episode, 39 (12.8%) responded positive to having experienced one or more past depressive episodes, and 226 (74%) reported that they had never experienced a depressive episode. In terms of suicidality, 236 (77.4%) reported no level of current suicide risk and lifetime suicide attempts; 38 (12.5%), 24 (7.9%), and 7 (2.3%) reported low, intermediate, and high levels of suicidality, respectively. The significant difference in suicidality in terms of gender, t (118)=2.797, p=0.006, supported the need to control the variable during regression analysis.

Table 1.

Demographic information of the participants

| Participants (N=305) | |

|---|---|

| Gender (%) | |

| Male | 87 (28.5) |

| Female | 218 (71.5) |

| Age (year) | 41.05±14.48 |

| Education (year) | 14.43±4.06 |

| Beck Depression Inventory-II | 12.82±11.57 |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | 8.70±11.18 |

| Korean Heartland Forgiveness Scale | 80.58±16.32 |

| Forgiveness-of-self | 27.17±6.43 |

| Forgiveness-of-others | 26.02±6.11 |

| Forgiveness-of-situation | 27.39±6.29 |

| M.I.N.I. suicidality (%) | 0.35±0.73 |

| None (0) | 236 (77.4) |

| Low (1) | 38 (12.5) |

| Intermediate (2) | 24 (7.9) |

| High (3) | 7 (2.3) |

| M.I.N.I. depression (%) | |

| None | 226 (74.1) |

| Past depressive episode | 39 (12.8) |

| Current depressive episode | 40 (13.1) |

The total score of the BDI-II was calculated without item 9. Suicidality=the present level of current suicide risk and lifetime suicide attempts (low risk: 1-5, intermediate: 6-9, and high risk: >9). M.I.N.I.: Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

Intercorrelations between each variable are presented in Table 2. Significant positive correlations were identified between BDI-II and BAI, r (305)=0.80, p<0.001, BDI-II and suicidality, r (305)=0.61, p<0.001, and BAI and suicidality, r (305)=0.57, p<0.001. In addition, significant negative correlations were identified between BDI-II and K-HFS, r (305)=-0.67, p<0.001, BDI-II and forgiveness-of-self, r (305)=-0.68, p<0.001, BDI-II and forgiveness-of-others, r (305)=-0.46, p<0.001, and BDI-II and forgiveness-of-situation, r (305)=-0.60, p<0.001. Significant negative correlations were also identified between BAI and K-HFS, r (305)=-0.56, p<0.001, and each of its subscales r (305)=-0.54, p<0.001, r (305)=-0.40, p<0.001, r (305)=-0.51, p<0.001, respectively. Moreover, suicidality was negatively associated with K-HFS r (305)=-0.52, p<0.001 and each of its subscales, r (305)=-0.50, p<0.001, r (305)=-0.38, p<0.001, r (305)=-0.48, p<0.001, respectively.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations between BDI-II, BAI, K-HFS, forgiveness-of-self, forgiveness-of-others, forgiveness-of-situation and suicidality (N=305)

| BDI-II | BAI | K-HFS | Forgiveness-of-self | Forgiveness-of-others | Forgiveness-of-situation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI-II | - | |||||

| BAI | 0.80*** | - | ||||

| K-HFS | -0.67*** | -0.56*** | - | |||

| Forgiveness-of-self | -0.68*** | -0.54*** | 0.86*** | - | ||

| Forgiveness-of-others | -0.46*** | -0.40*** | 0.84*** | 0.52*** | - | |

| Forgiveness-of-situation | -0.60*** | -0.51*** | 0.91*** | 0.69*** | 0.67*** | - |

| Suicidality | 0.61*** | 0.57*** | -0.52*** | -0.50*** | -0.38*** | -0.48*** |

The total score of the BDI-II was calculated without item 9.

p<0.001.

BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II, BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory, K-HFS: Korean Heartland Forgiveness Scale

Moderation effects

The results of the regression analyses are shown in Table 3 and 4. The results of the hierarchical regression analysis that inspected forgiveness (K-HFS) as the moderating variable were as follows. Model 1, which included gender and anxiety was significant, R2=0.34, F (2, 302)=77.62, p<0.001. Examination of independent variables indicated that BAI, β=0.55, t (302)=11.81, p<0.001, and gender both predicted suicidality, β=-0.14, t (302)=-2.94, p<0.01. Model 2, which included depression and forgiveness (K-HFS), explained an additional 8% of the variance to demonstrate its significance in predicting suicidality, R2=0.42, F (4, 300)=37.25, p<0.001. Both depression, β=0.33, t (300)=4.08, p<0.01, and forgiveness (K-HFS), β=-0.18, t (300)=-2.95, p<0.01, demonstrated significant main effects. Model 3, which accounted for the interaction between depression and forgiveness (K-HFS), explained an additional 3% of the variance and proved to be a significant predictor of suicidality, R2=0.45, F (5, 299)=29.82, p<0.001. As we expected, the interaction between depression and forgiveness (K-HFS), β=-0.22, t (299)=-4.27, p<0.001, demonstrated significance.

Table 3.

Hierarchical regression analysis examining the moderation effects of forgiveness (N=305)

| Predicting variables | F value | R2 | df | β | t value | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 77.62 | 0.34 | 302 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | -0.14 | -2.94 | <0.01 | ||||

| BAI | 0.55 | 11.81 | <0.001 | ||||

| 2 | 37.25 | 0.42 | 300 | <0.001 | |||

| BDI-II | 0.33 | 4.08 | <0.001 | ||||

| K-HFS | -0.18 | -2.95 | <0.01 | ||||

| 3 | 29.82 | 0.45 | 299 | <0.001 | |||

| BDI-II×K-HFS | -0.22 | -4.27 | <0.001 | ||||

Dependent variable=Suicidality. The total score of the BDI-II was calculated without item 9. BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II, BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory, K-HFS: Korean Heartland Forgiveness Scale

Table 4.

Hierarchical regression analysis with forgiveness subtypes as moderators (N=305)

| Predicting variables | F value | R2 | df | β | t value | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 77.62 | 0.34 | 302 | <0.001 | |||

| Gender | -0.14 | -2.94 | 0.004 | ||||

| BAI | 0.55 | 11.81 | <0.001 | ||||

| 2 | 37.25 | 0.42 | 298 | <0.001 | |||

| BDI-II | 0.32 | 3.80 | <0.001 | ||||

| Forgiveness-of-self | -0.08 | -1.22 | 0.225 | ||||

| Forgiveness-of-others | -0.03 | -0.47 | 0.637 | ||||

| Forgiveness-of-situation | -0.10 | -1.35 | 0.179 | ||||

| 2 | 29.82 | 0.46 | 295 | <0.001 | |||

| BDI-II×Forgiveness-of-self | -0.30 | -3.54 | <0.001 | ||||

| BDI-II×Forgiveness-of-others | -0.10 | -1.29 | 0.197 | ||||

| BDI-II×Forgiveness-of-situation | 0.18 | 1.21 | 0.227 | ||||

Dependent variable=Suicidality. The total score of the BDI-II was calculated without item 9. BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II, BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory

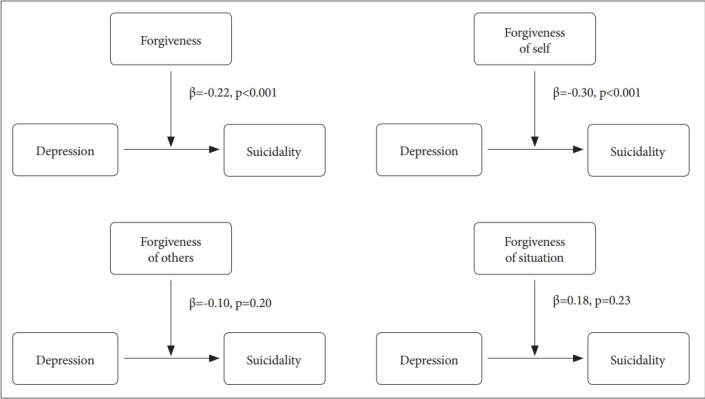

The results of the hierarchical analysis that incorporated the subtypes of forgiveness as the moderating variables are as follows. Model 1, which included gender and anxiety, R2=0.34, F (2, 302)=77.62, p<0.001, demonstrated significance. Both BAI, β=0.55, t (302)=11.81, p<0.001, and gender, β=-0.14, t (302)=-2.94, p<0.01, displayed significant main effects. Model 2, which included depression, forgiveness-of-self, forgiveness-of-others, and forgiveness-of-situation, explained an additional 8% of the variance and demonstrated significance in predicting suicidality, R2=0.42, F (4, 298)=37.25, p<0.001. No main effects were found for all three subtypes of forgiveness. Model 3, which included the interactions between depression and the forgiveness configurations, explained an additional 4% of the variance and proved to be a significant predictor of suicidality, R2=0.46, F (3, 295)=29.82, p<0.001. As hypothesized, only the interaction between depression and forgiveness-of-self, β=-0.30, t (295)=-3.54, p<0.001, demonstrated significance; the interactions between depression and forgiveness-of-others, and depression and forgiveness-of-situation were unsupported.

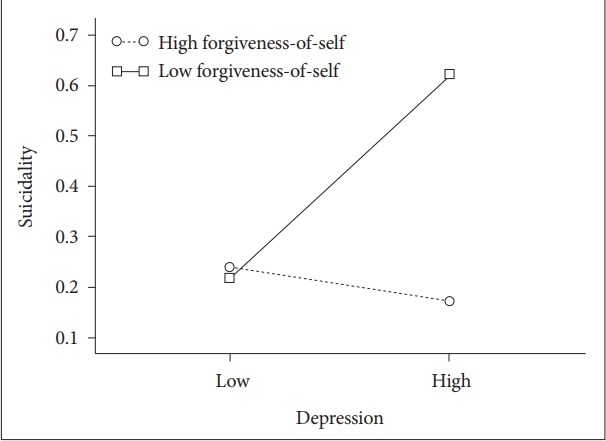

The interactions were plotted in Figure 1. Results indicated that the direction of the interaction between depression and self-forgiveness were consistent with our hypothesis. More specifically, those who demonstrated low levels of self-forgiveness were more vulnerable to suicide even if they had low levels of depression. On the other hand, those who were highly self-forgiving were less vulnerable to suicide regardless of their high level of depression. To recap, self-forgiveness alleviated the effects of depression on suicidality and was identified as a protective factor. Additional moderating effects of forgiveness as a whole, forgiveness-of-others, and forgivenessof-situation have been illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Interaction effects between depression and forgivenessof-self in predicting suicidality. Depression was measured by BDI-II, and Suicidality was measured by Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; The total score of the BDI-II was calculated without item 9. BDI-II: Beck Depression Inventory-II.

Figure 2.

Forgiveness as a moderator between depression and suicidality. Depression was measured by BDI-II, and suicidality was measured by Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; The total score of the BDI-II was calculated without item 9.

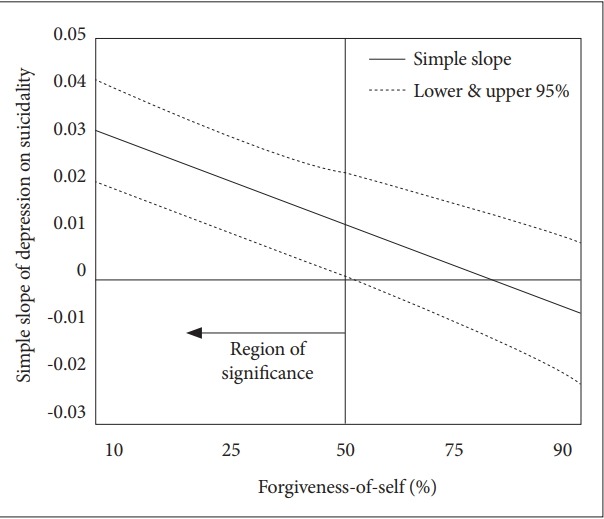

Table 5 presents the results from the Johnson-Neyman analysis. As shown in Table 5, the conditional indirect effect was significant when the raw score of self-forgiveness was below 27.59. Conversely, the conditional indirect effect was not significant when the raw score of self-forgiveness exceeded 27.59. The results imply that in the case of high self-forgiveness (more than 27.59), levels of suicidality remain constant and do not increase along with levels of depression. However, a transition was identified in those who displayed the highest level of self-forgiveness. More specifically, when the raw score of self-forgiveness exceeded 41.12, the conditional indirect effect was once again significant. This result implies that suicidality significantly increased along with levels of depression in those who portrayed the highest level of self-forgiveness (above 41.12). Overall, the moderating effect was significant in 46.23% of the participants (between 27.59 and 41.12), and insignificant in 53.77% of the participants (below 27.59 and above 41.12) (Figure 3).

Table 5.

Moderating effects on the raw score of forgiveness-of-self (N=305)

| Forgiveness-of-self | Effect | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.00 | 0.06 | 0.01 | 6.72 | 0.00 | 0.040 | 0.073 |

| 7.80 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 6.72 | 0.00 | 0.037 | 0.068 |

| 9.60 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 6.70 | 0.00 | 0.035 | 0.063 |

| 11.40 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 6.64 | 0.00 | 0.032 | 0.058 |

| 13.20 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 6.53 | 0.00 | 0.029 | 0.054 |

| 15.00 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 6.33 | 0.00 | 0.026 | 0.049 |

| 16.80 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 6.04 | 0.00 | 0.023 | 0.045 |

| 18.60 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 5.62 | 0.00 | 0.019 | 0.040 |

| 20.40 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 5.07 | 0.00 | 0.016 | 0.036 |

| 22.20 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 4.38 | 0.00 | 0.012 | 0.032 |

| 24.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 3.60 | 0.00 | 0.008 | 0.028 |

| 25.80 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 2.78 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.025 |

| 27.59 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.97 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.022 |

| 27.60 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.96 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 0.022 |

| 29.40 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.19 | 0.23 | -0.005 | 0.018 |

| 31.20 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.50 | 0.62 | -0.009 | 0.015 |

| 33.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | -0.11 | 0.91 | -0.014 | 0.012 |

| 34.80 | 0.00 | 0.01 | -0.64 | 0.52 | -0.019 | 0.010 |

| 36.60 | -0.01 | 0.01 | -1.09 | 0.28 | -0.023 | 0.007 |

| 38.40 | -0.01 | 0.01 | -1.48 | 0.14 | -0.028 | 0.004 |

| 40.20 | -0.02 | 0.01 | -1.82 | 0.07 | -0.033 | 0.001 |

| 41.12 | -0.02 | 0.01 | -1.97 | 0.05 | -0.036 | 0.000 |

| 42.00 | -0.02 | 0.01 | -2.10 | 0.04 | -0.038 | -0.001 |

LLCI, ULCI: lower and upper limits within the 95% confidence interval of the moderating effects

Figure 3.

Johnson-Neyman plot of the simple slope of depression on suicidality across the range of forgiveness-of-self. Depression was measured by BDI-II, and suicidality was measured by Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; The total score of the BDI-II was calculated without item 9. CI: confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we investigated forgiveness as a moderator of depression and suicidality. In particular, we were interested in identifying which dispositional forgiveness (i.e., forgiveness-of-self, forgiveness-of-others, and forgiveness-of-situation) would interact with depression to predict suicide. Significant results included that 1) depression was not only positively correlated with suicide but was a valid predictor even when controlling for gender and anxiety, 2) forgiveness moderated the influence of depression on suicidality, 3) among the three subtypes of forgiveness, only forgiveness-of-self interacted with depression to predict suicidal behaviors, and 4) an increase in self-forgiveness was a protective factor of suicidal behaviors, however, only to a certain point.

First, a positive correlation between depression and suicidality was found in our study, which is consistent with the existing literature. Previous studies have suggested mood disorders as one of the most prominent predictors of suicidal behaviors [30,31,38]. According to Cheavens et al. [39] depending on the definition of suicide ideation, its prevalence can be as high as 70% in patients with major depressive disorder. However, the results from our hierarchical regression analysis go beyond previous findings to suggest that depression is a robust predictor of suicide even when controlling for anxiety.

Second, forgiveness significantly moderated the path between depression and suicidality. In a previous study by Hirsch et al. [11] self-forgiveness was mediated by depression to predict suicidal behaviors. However, multiple studies have found forgiveness to significantly reduce depressive symptoms [3,8]. A recent meta-analysis indicated that forgiveness interventions increased levels of forgivingness, while decreasing levels of depression [40]. If so, it would be more reasonable to examine forgiveness as a moderator of depression instead. Moreover, Hirsch et al. [11] utilized a single item measure to assess dispositional forgiveness. Hence, a more elaborative examination of the relationship between depression, forgiveness, and suicidality was warranted. Our results support the argument by Sadowski and Kelley [6] that resilience factors (e.g., forgiveness) ought to be considered along with risk factors in order to optimize the prediction of suicidal behaviors. Furthermore, our findings might provide an explanation as to why not all depressive patients display suicidal behaviors; levels of forgiveness might reduce the negative effects of depression that lead to the development of suicidal desires.

Third, among the three forgiveness configurations only selfforgiveness moderated the influence of depression on suicidality. No moderating effects were found in forgiveness-of-others and forgiveness-of-situation. Moreover, these results were supported while controlling for anxiety. Our results are consistent with prior findings in the sense that self-forgiveness indirectly predicted suicidal behaviors through moderating depression. According to Hirsch et al. [12] self-forgiveness interacted with both inward and outward anger to predict suicidal behaviors. In addition, forgiveness-of-self moderated the path between perceived burdensomeness, a core construct of suicidal desire that consists of self-hatred and the misconception that one is a burden [41], and suicide ideation [39].

A particularly interesting finding of the present study was that only forgiveness-of-self was identified as a significant moderator of depression and suicide, whereas forgiveness-of-others and forgiveness-of-situations were not. This bolsters the perspectives of previous theories on suicide that assert negative self-image as a necessary component of suicidal behaviors [19,41,42]. Moreover, our results support the argument that the lack of forgiveness-of-others can lead to interpersonal issues, whereas low levels of forgiveness-of-self can lead to more lethal outcomes such as self-destruction [43]. Hence, enhancing self-forgiveness and ultimately increasing self-acceptance is crucial to reducing suicidal behaviors [20,34]. Future studies ought to examine the underlying mechanisms in which forgiveness-of-self operates in order to reduce suicidality.

Lastly, our results indicated that typically a high level of selfforgiveness, in our case a score over 27.59, reduced risks to suicidal behaviors. However, not only too less, but too much self-forgiveness was identified as detrimental. Although forgiveness-of-self has been usually understood to be beneficial to an individual’s health, there have been suggestions that too much self-forgiveness can have maladaptive outcomes. For example, it has been suggested that self-forgiveness can prolong wrongful behaviors (e.g., smoking) by freeing individuals from associated negative feelings [44,45]. Moreover, self-forgiveness might promote narcissistic behavior [46], which is a possibility considering that some of our participants who scored the highest on forgiveness-of-self, had exceptionally low scores on forgiveness-of-others, and forgiveness-of-situations. Such results might derive from the fact that self-forgiveness is often mistaken for excusing oneself [47,48].

Despite the significant findings of this study, there are some limitations. First, we measured suicidality as a single concept. However, literature suggests suicide as a heterogeneous construct composed of ideation and behaviors (e.g., planning and attempt) [49-51], and an individual examination of suicide ideation and suicidal attempt might produce distinct results. Second, the gender of our sample was heavily biased towards females. Although we controlled the effects of gender in our analyses, this limits the generalizability of our results.

Our study is one of the few that has examined specific configurations of forgiveness as moderators of depression and suicidality. Although multiple factors play into the development of suicidal behaviors, forgiveness seems to be a crucial element in their reduction. In particular, forgiveness-of-self was identified to be essential. Hence, suicide prevention programs ought to focus on promoting self-forgiveness in order to reduce one’s risk of suicide.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Brain Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (NRF-2015M3C7A1028252), and the Korea Science and Engineering Foundation (KOSEF) funded by the Korean government (NRF-2018R1A2A2A05018505).

REFERENCES

- 1.Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Alonso J, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, et al. Cross-national prevalence and risk factors for suicidal ideation, plans and attempts. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:98–105. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chesney E, Goodwin GM, Fazel S. Risks of all‐cause and suicide mortality in mental disorders: a meta‐review. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:153–160. doi: 10.1002/wps.20128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holma KM, Melartin TK, Haukka J, Holma IA, Sokero TP, Isometsä ET. Incidence and predictors of suicide attempts in DSM-IV major depressive disorder: a five-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:801–808. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09050627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behav Res. 2005;40:373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rihmer Z. Suicide risk in mood disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20:17–22. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3280106868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sadowski C, Kelley ML. Social problem solving in suicidal adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:121–127. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.61.1.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davydov DM, Stewart R, Ritchie K, Chaudieu I. Resilience and mental health. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:479–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zautra AJ, Hall JS, Murray KE, Resilience Solutions Group. Resilience: a new integrative approach to health and mental health research. Health Psychol Rev. 2008;2:41–64. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rutter M. Resilience in the face of adversity. Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:598–611. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryan AO, Theriault JL, Bryan CJ. Self-forgiveness, posttraumatic stress, and suicide attempts among military personnel and veterans. Traumatology. 2015;21:40–46. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hirsch JK, Webb JR, Jeglic EL. Forgiveness, depression, and suicidal behavior among a diverse sample of college students. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:896–906. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirsch JK, Webb JR, Jeglic EL. Forgiveness as a moderator of the association between anger expression and suicidal behaviour. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2012;15:279–300. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu X, Lu D, Zhou L, Su L. Forgiveness as a moderator of the association between victimization and suicidal ideation. Indian Pediatr. 2013;50:685–688. doi: 10.1007/s13312-013-0191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sansone RA, Kelley AR, Forbis JS. The relationship between forgiveness and history of suicide attempt. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2013;16:31–37. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Webb JR, Hirsch JK, Toussaint L. Forgiveness as a positive psychotherapy for addiction and suicide: Theory, research, and practice. Spiritual Clin Pract. 2015;2:48–60. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reed GL, Enright RD. The effects of forgiveness therapy on depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress for women after spousal emotional abuse. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:920–929. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson LY, Snyder CR, Hoffman L, Michael ST, Rasmussen HN, Billings LS, et al. Dispositional forgiveness of self, others, and situations. J Pers. 2005;73:313–360. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freud S. Mourning and Melancholia. In: Strachey J, editor. Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. London: Hogarth Press; 1917. pp. 237–258. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baumeister RF. Suicide as escape from self. Psychol Rev. 1990;97:90–113. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.97.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Psychoanalytic Theories of Suicide: Historical Overview and Empirical Evidence. In: Oxford Textbook of Suicidology and Suicide Prevention. Wasserman D, Wasserman C, editors. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. pp. 149–158. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim SU, Lee EH, Hwang ST, Hong SH, Kim JH. Psychometric Properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in Korea. Paper presented at the 2014 Fall Conference of the Korean Clinical Psychology Association; Ilsan, Korea. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. 1996;78:490–498. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beck AT, Steer RA. Manual for the Beck Anxiety Inventory. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, et al. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. Eur Psychiatry. 1997;12:232–241. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoo SW, Kim YS, Noh JS, Oh KS, Kim CH, NamKoong K, et al. Validity of Korean version of the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview. Anxiety Mood. 2006;2:50–55. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hong HG, Lee JE, Kim JK, Kang KH, Lee SM, Hyun MH. Validation Study of the Korean Heartland Forgiveness Scale (K-HFS) Korean J Health Psychol. 2016;21:607–621. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayes AF. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Publications; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim S, Kim JS, Jin MJ, Im CH, Lee SH. Dysfunctional frontal lobe activity during inhibitory tasks in individuals with childhood trauma: an event-related potential study. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;17:935–942. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2017.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westfall PH. On using the bootstrap for multiple comparisons. J Biopharm Stat. 2011;21:1187–1205. doi: 10.1080/10543406.2011.607751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Girard C. Age, gender, and suicide: a cross-national analysis. Am Sociol Rev. 1993;58:553–574. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nock MK, Hwang I, Sampson N, Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Beautrais A, et al. Cross-national analysis of the associations among mental disorders and suicidal behavior: findings from the WHO World Mental Health Surveys. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sareen J, Cox BJ, Afifi TO, de Graaf R, Asmundson GJ, ten Have M, et al. Anxiety disorders and risk for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts: a population-based longitudinal study of adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:1249–1257. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson PO, Neyman J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Stat Res Memoirs. 1936;1:57–93. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayes A. An Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kerlinger FN, Pedhazur EJ. Multiple Regression in Behavioral Sciences. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2006;31:437–448. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Franklin JC, Ribeiro JD, Fox KR, Bentley KH, Kleiman EM, Huang X, et al. Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: a meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2017;143:187–232. doi: 10.1037/bul0000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheavens JS, Cukrowicz KC, Hansen R, Mitchell SM. Incorporating resilience factors into the interpersonal theory of suicide: the role of hope and self‐forgiveness in an older adult sample. J Clin Psychol. 2016;72:58–69. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baskin TW, Enright RD. Intervention studies on forgiveness: a metaanalysis. J Counsel Develop. 2004;82:79–90. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Joiner T. Why People Die by Suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bushman BJ. Does venting anger feed or extinguish the flame? Catharsis, rumination, distraction, anger, and aggressive responding. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2002;28:724–731. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hall JH, Fincham FD. Self-forgiveness: the stepchild of forgiveness research. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2005;24:621–637. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wohl MJ, McLaughlin KJ. Self‐forgiveness: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Soc Pers Psychol Compass. 2014;8:422–435. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wohl MJ, Thompson A. A dark side to self‐forgiveness: Forgiving the self and its association with chronic unhealthy behaviour. Br J Soc Psychol. 2011;50:354–364. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vitz PC, Meade JM. Self-forgiveness in psychology and psychotherapy: a critique. J Relig Health. 2011;50:248–263. doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9343-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Enright RD. Counseling within the forgiveness triad: on forgiving, receiving forgiveness, and self‐forgiveness. Counsel Values. 1996;40:107–126. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fisher ML, Exline JJ. Self-forgiveness versus excusing: the roles of remorse, effort, and acceptance of responsibility. Self Identity. 2006;5:127–146. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reynolds WM. SIQ, Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire: Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with the onset of suicidal behaviour during adolescence and early adulthood. Psychol Med. 2000;30:23–39. doi: 10.1017/s003329179900135x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harwood D, Jacoby R. Suicidal Behaviour among the Elderly. In: Hawton K, Van Heeringen K, editors. The International Handbook of Suicide and Attempted Suicide. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd; 2000. pp. 275–291. [Google Scholar]