Abstract

Objective:

To review systematically medical-legal cases of sleep-related violence (SRV) and sexual behavior in sleep (SBS).

Search Methods:

We searched Pubmed and PsychINFO (from 1980 to 2012) with pre-specified terms. We also searched reference lists of relevant articles.

Selection Criteria:

Case reports in which a sleep disorder was purported as the defense during a criminal trial and in which information about the forensic evaluation of the defendant was provided.

Data Extraction and Analysis:

Information about legal issues, defendant and victim characteristics, circumstantial factors, and forensic evaluation was extracted from each case. A qualitative-comparative assessment of cases was performed.

Results:

Eighteen cases (9 SRV and 9 SBS) were included. The charge was murder or attempted murder in all SRV cases, while in SBS cases the charge ranged from sexual touching to rape. The defense was based on sleepwalking in 11 of 18 cases. The trial outcome was in favor of the defendant in 14 of 18 cases. Defendants were relatively young males in all cases. Victims were usually adult relatives of the defendants in SRV cases and unrelated young girls or adolescents in SBS cases. In most cases the criminal events occurred 1-2 hours after the defendant's sleep onset, and both proximity and other potential triggering factors were reported. The forensic evaluations widely differed from case to case.

Conclusion:

SRV and SBS medical-legal cases did not show apparent differences, except for the severity of the charges and the victim characteristics. An international multidisciplinary consensus for the forensic evaluation of SRV and SBS should be developed as an urgent priority.

Citation:

Ingravallo F, Poli F, Gilmore EV, Pizza F, Vignatelli L, Schenck CH, Plazzi G. Sleep-related violence and sexual behavior in sleep: a systematic review of medical-legal case reports. J Clin Sleep Med 2014;10(8):927-935.

Keywords: sleep violence, sexsomnia, parasomnia, criminal law, forensic evaluation, sleepwalking defense

Sleep-related violence (SRV) and sexual behavior in sleep (SBS) represent a challenging medical-legal issue when such behaviors are suspected or purported to have caused a criminal offense (e.g., assault, attempted murder, murder, sexual assault). Indeed, SRV and SBS can and do arise from the sleep period, without full consciousness, and therefore without responsibility for the offender.1

SRV subsumes a wide spectrum of behaviors ranging from very simple or semi-purposeful behavioral manifestations to more complex, inappropriate acts that could be directed to oneself, to the bed partner, or to objects. Ohayon and Schenck found that violent or injurious behaviors during sleep (e.g., punching, kicking, leaping, and running away from the bed while acting out dreams) are reported by 1.6% of the general population.2 SRV can occur during parasomnias (confusional arousals, sleepwalking, sleep terrors, REM behavior disorder [RBD], and parasomnia overlap disorder) or during nocturnal (i.e., sleep-related) seizures.1,3,4 SBS ranges from explicit sexual vocalizations/moaning/talking/shouting, genital bruising/(even violent) masturbation, to fondling another person, and complex sexual acts and agitated/assaultive sexual behaviors.5–9 Sleep related abnormal sexual behaviors, also called sexsomnia or sleepsex, are primarily classified as confusional arousals but have also been less commonly associated with sleepwalking,10 although some authors suggest that they be classified as a distinct entity for its unique combination of specific motor and autonomic activation.7 Abnormal sexual behaviors during sleep are also reported in association with RBD,11,12 parasomnia overlap disorder,13 obstructive sleep apnea (OSA),6,8,12,14 and sleep-related seizures.8 Besides several scientific articles addressing forensic issues of SRV and SBS,4,8,15–25 two previous works have reviewed criminal cases implicating sleep disorders.26,27 However, both the above reviews present two limitations. First, they combined different types of reports (medical and legal) and sources (articles, books, media) without a systematic approach. Second, collecting cases from 160027 and 1791,26 respectively, they hamper a diagnostic comparison of the reported cases. Modern sleep medicine research, indeed, developed only from the early part of the 20th century, and a formal classification of sleep disorders was not available until 1979, when the first “Diagnostic classification of sleep and arousal disorders” was published.28

The present review focuses on medical-legal cases published since 1980 in which a sleep disorder was purported as defense during the criminal trial. Sleep experts' reports and testimonies were pivotal in these cases, whether they were appointed by the prosecution, by the defense, or by the court.

The research questions were:

a) What were the legal issues of these cases?

b) What were the defendant and the victim characteristics?

c) What circumstantial factors were identified?

d) What type of forensic evaluation was carried out?

Additionally, recommendations for a sleep expert evaluation are provided.

METHODS

Inclusion Criteria

We included articles written in English published from 1980 to 2012 reporting cases in which a sleep disorder was purported as the defense during a criminal trial and in which information about the forensic evaluation of the defendant was provided.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

An electronic literature search of articles published from January 1980 through December 2012 was performed in Pubmed and PsychINFO databases. Two search strategies were used. The first included terms indexed in MeSH and Thesaurus vocabularies respectively: (crime OR criminal law OR insanity defense (defence)) AND (sleep OR parasomnia*). The second search was performed with the following free terms: “sleep violence” OR “violent behavio(u)r during sleep” OR “sleep-related violence” OR “sexsomnia” OR “sleep sex” OR “sleep-related abnormal sexual behavio(u)r” OR “sleepwalking defense (defence).”

Two of the review authors screened titles and abstracts independently to identify potentially relevant articles. The reference lists of these articles were also screened for additional relevant sources. Two reviewers obtained and scrutinized the full texts of articles of interest. Disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer.

Data Extraction and Assessment

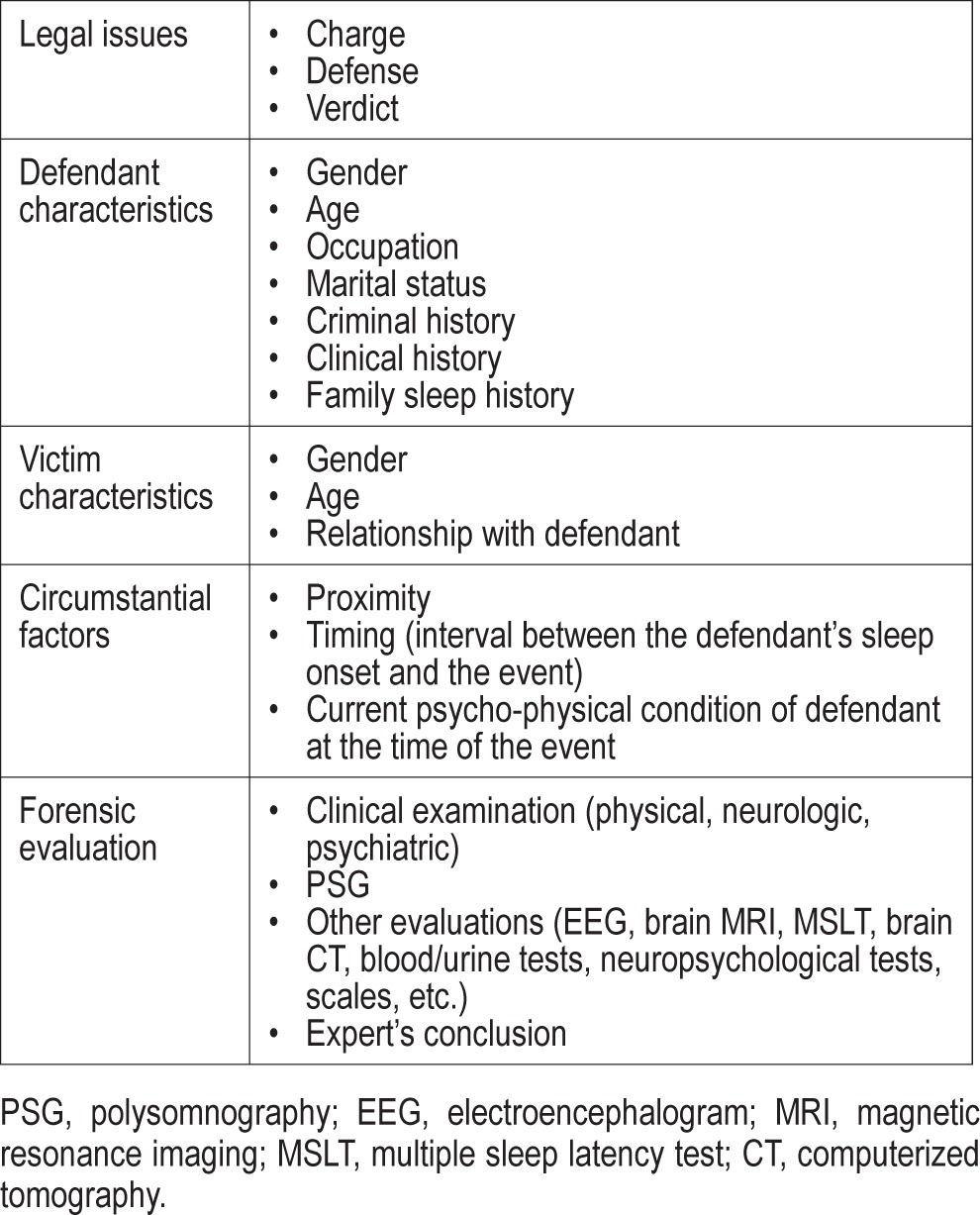

Three of the authors extracted from each case a set of medical-legal key elements (Table 1). A qualitative-comparative assessment of cases was performed.

Table 1.

Medical-legal key elements

RESULTS

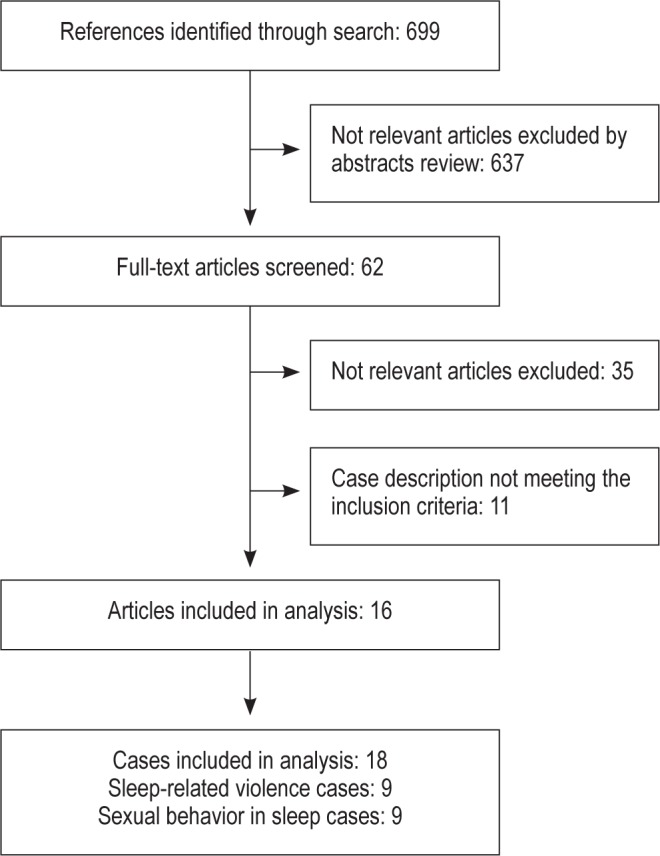

We found 699 references; all abstracts were screened and 62 articles with potentially relevant material were examined in detail, leading to the final identification of 27 articles (26 in Pubmed and 1 in PsychINFO), containing a total of 35 medical-legal cases.

Sixteen of the above 27 articles, reporting a total of 18 cases (9 of SRV29–36 and 9 of SBS6,7,13,37–41), met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The selected articles were published from 1985 to 2011 and included 9 single case reports,31–34,36–39,41 and 7 case series with at least 1 medical-legal case.6,7,13,29,30,35,40 Seven articles were published in psychiatry journals,6,7,29,30,34,35,38 5 in legal medicine journals,33,36,37,39,41 3 in sleep medicine journals,13,31,32 and 1 in a sexual medicine journal.40 In cases fulfilling the inclusion criteria but lacking data regarding the trial outcome, we directly contacted the authors. Each case was summarized in terms of the description of the event, the legal charge(s), the defense, the forensic evaluation, and the court verdict (Table 2 and Table 3).

Figure 1. The selection of studies included in the systematic review.

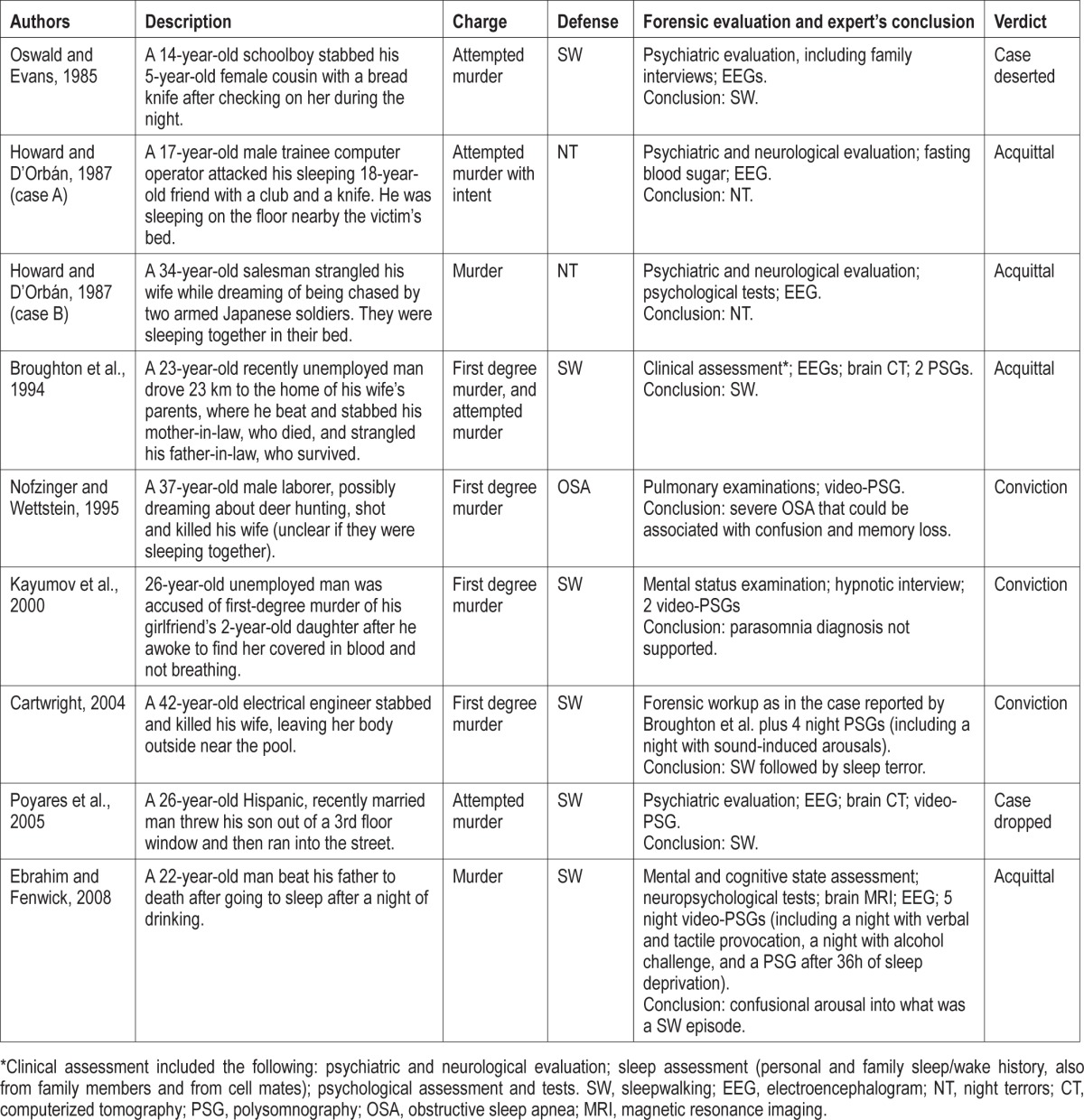

Table 2.

Sleep-related violence cases

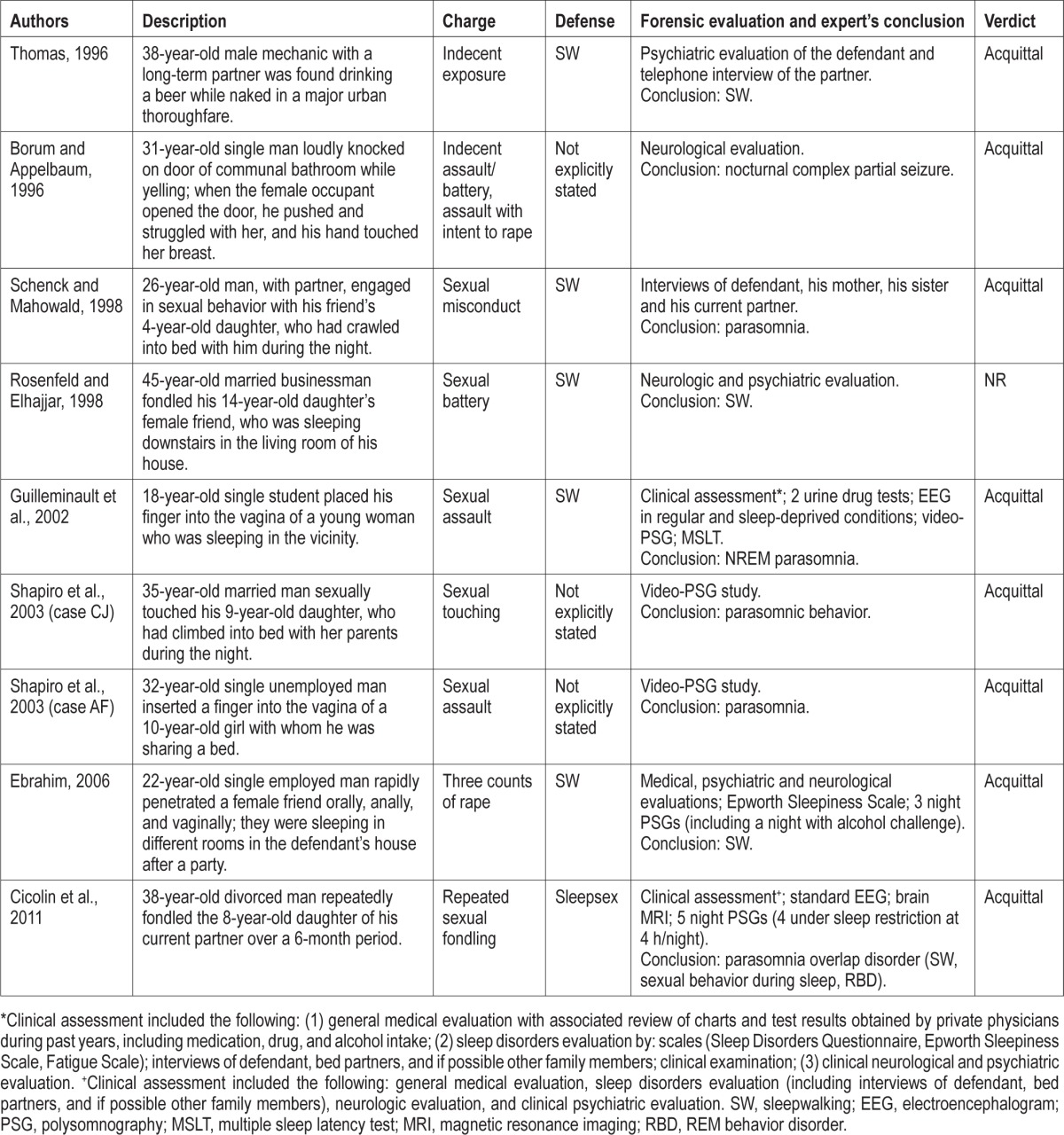

Table 3.

Sexual behavior in sleep cases

The remaining 11 articles, reporting a total of 18 cases, were excluded because it was not clear whether the sleep disorder was actually purported as the defense during the trial, or because information about the forensic evaluation was lacking. A description of excluded cases is reported in Table S1 (supplemental material).

Sleep-Related Violence Cases (Table 2)

Legal Issues

All 9 SRV cases reported on a single criminal episode. The legal charge was “murder” in 5 cases (including case B reported by Howard and D'Orbán),30,32–34,36 “attempted murder” in 3 cases (with case A reported by Howard and D'Orbán),29,30,35 and “murder and attempted murder.”31

At trial, the defense was based on sleepwalking in 6 cases,29,31,33–36 on night terrors in 2 cases,30 and on a confusional state related to arousals associated with OSA in 1 case.32

The verdict was in favor of the defendant in 6 of 9 cases: 4 defendants were acquitted,30,31,36 while in 2 trials the charges were dropped.29,35 In 3 cases, the defendant was convicted.32–34

Defendant Characteristics

All 9 defendants were male, with a mean age 26.8 ± 9.3 years (range 14-42 years). Seven reports mentioned the defendant's occupation at the time of the event: 3 defendants were employed (including case B from Howard and D'Orbán),30,32,34 2 were students (including case A from Howard and D'Orbán),29,30 and 2 were unemployed.31,33 In 6 cases, the defendants were married (including case B from Howard and D'Orbán)30–32,34,35 or had a partner.33 Previous criminal history was mentioned in 6 cases: although defendants did not have convictions, a history of previous shoplifting,29 episodes of theft at work,31 and abusive behaviors towards previous and current wives and children32 were reported.

An ongoing sleep disturbance was reported in 4 cases: sleepwalking,35 sleep talking,29 sleepwalking associated with sleep talking and enuresis,31 and night wandering episodes with a long history of snoring,36 respectively. Prior histories of parasomnias were reported in 4 cases.30,32,34 In 5 of 8 cases with an ongoing or past sleep disorder, sleep-related complex behaviors (including Howard and D'Orbán case B),29–31,34–36 were reported, along with 3 cases of sleep-related violent behaviors (with Howard and D'Orbán case B).29,30,34

Consequences of a serious head injury three years previously (mild disability and moderate degree of residual posttraumatic personality change) were reported in 1 case (Howard and D'Orbán case B),30 and a history of pathological gambling in another.31

Information about the defendant's family sleep history was reported in 4 of 9 cases and included isolated sleepwalking36 or multiple parasomnias (sleepwalking, sleep talking, sleep terrors, bedwetting, and confusional arousals31or bruxism34). In 1 case, there was a negative family history for any sleep disorder.29

Victim Characteristics

Of 10 victims, 6 were females. The victims were 7 adults and 3 minors, but their exact age was reported only in 3 cases (including Howard and D'Orbán case A).29,30,35 In only 1 case, the crime had 2 victims, the defendant's parents-in-law.31 The other victims' relations to the defendant included 1 son,35 1 father,36 3 wives (including Howard and D'Orbán case B),30,32,34 1 daughter of a partner,33 1 cousin,29 and 1 friend (Howard and D'Orbán case A).30

Circumstantial Factors

In most of the cases, the defendant and the victim were sleeping under the same roof: in the same bed in 1 case (Howard and D'Orbán case B),30 in the same room in 1 case (Howard and D'Orbán case A),30 in different rooms in 3 cases,29,34,36 while in 3 other cases it was not specified whether they were sleeping in the same room or bed.32,33,35 In 1 case,31 the defendant was sleeping at home prior to the abrupt onset of sleepwalking and driving 23 kilometers to the victims' house.

The time span between the defendant's sleep onset and the criminal event was reported in 6 of 9 cases; in all the cases, the criminal event occurred within 1 to 2 hours after the defendant's sleep onset.30–32,34,36

Details about the psycho-physical condition of the defendant at the time of the alleged event included: exposure to stress,29,31,34–36 sleep deprivation,31,35 unspecified33 or excessive36 alcohol intake, fatigue along with caffeine overuse (with Howard and D'Orbán case A),30,34 either alone or variably associated.

Forensic Evaluation

The forensic evaluation of the defendant included routine electroencephalogram (EEG) and a psychiatric and/or neurological assessment in 3 cases,29,30 and polysomnography (PSG)31,34 or video-PSG32,33,35,36 in 6 cases (the number of recorded nights ranged from 1 to 6). Provocative stimuli during the PSG were administered in 2 cases: “sound induced arousals” in 1 case,34 and “verbal and tactile provocation,” “alcohol challenge,” and 36 hours of sleep deprivation (each provocation was administered on non-consecutive nights) in the other case.36 Detailed PSG findings were described in all cases who underwent sleep-lab studies. All the defendants who underwent PSG study also had additional clinical and/or instrumental evaluations (psychological/mental/cognitive assessments and tests; EEG; brain computerized tomography; brain magnetic resonance imaging, etc.). Seven of 9 defendants had a final diagnosis of parasomnia: sleepwalking in 3 cases,29,31,35 sleep terrors in 2 cases,30 “confusional arousal into what was a sleepwalking episode” in 1 case,36 and “sleepwalking followed by sleep terror” in 1 case.34 The expert evaluation did not support the diagnosis of parasomnia in 1 case33 and resulted in a diagnosis of severe OSA in another one.32

Sexual Behavior in Sleep Cases (Table 3)

Legal Issues

The allegation regarded a single episode in all cases but one.13 Charges were: “sexual battery/assault” in 3 cases (including case AF reported by Shapiro et al.),6,7,40 “sexual touching/fondling” in 2 cases (including Shapiro et al. case CJ),7,13 “indecent exposure” in 1 case,37 “indecent assault and battery with intent to rape” in 1 case,38 “sexual misconduct” in 1 case,39 and “three counts of rape” in 1 case.41

At trial, the defense was based on sleepwalking in 5 cases,6,37,39–41 and on “parasomnia including sleepsex” in 1 case.13 In 3 cases, the legal defense was not explicitly stated, but the authors reported that evidence of a parasomnia7 and of epileptic postictal aggression38 were accepted in court.

In 7 of 9 cases, the verdict was reported and was in favor of the defendant. In 1 of the remaining 2 cases in which the trial outcome was unknown,6 we obtained information that the verdict was in favor of the defendant.

Defendant Characteristics

All 9 defendants were male, with a mean age of 31.7 ± 8.5 years (range 18-45 years). Five reports provided details on the occupations of the defendants at the time of the event: 3 were employed,37,40,41 1 was a student,6 and 1 was unemployed (Shapiro et al. case AF).7 The marital status of the defendants was reported in all cases: 5 were married (including Shapiro et al. case CJ)7,40 or had a partner,13,37,39 and 4 were single (including Shapiro et al. case AF).6,7,38,41 Reference to a prior criminal history was provided in 4 cases: 2 defendants had no previous charges or convictions,39,40 a 38-year-old man had been arrested for burglary at the age of 18,37 and 1 had a conviction for driving while intoxicated.37

In 6 of 9 cases, the defendants had a long clinical history of either isolated persistent sleepwalking,39 sleepwalking in association with other parasomnias,6,13,37,40 or snoring.41 Associated parasomnias consisted of sleep talking in 4 cases,6,13,37,40 (coupled in 1 case with sleep terrors and enuresis),6 and in 1 case sleep terrors and sleep behaviors “isomorphic with dream content.”13 In 4 cases, parasomnias were characterized by complex behaviors,13,37,40,41 and in 2 cases included sexual elements.13,41 In 1 case the defendant had a history of nocturnal complex partial seizures, followed by periods of postictal wandering and confusion.38

Clinical history was less suggestive in the remaining 2 cases, both reported by Shapiro et al.7: AF had a history of sleep talking but exhibited sleepwalking on only one occasion; while in the case of CJ, the defendant's sleep history was based upon his wife's recall, who reported that “there probably were times that he had spoken in his sleep (mumbling).”

Regarding past clinical features apart from sleep, a head injury at age 4 years and a gunshot wound to the head at age 22 years were reported in 1 case,37 and a history of previous alcohol abuse was reported in 2 cases (including the case AF by Shapiro et al.).7,38

Information about the defendant's family sleep history was reported in 4 of 9 cases and included sleepwalking in 2 cases,39,41 parasomnia not otherwise specified in 1 case (AF by Shapiro et al.),7 and sleepwalking plus sleep talking in the other one.13

Victim Characteristics

With the exception of the indecent exposure case, in which the defendant was seen by a male driver of an automobile to be drinking a beer while naked in a major thoroughfare,37 in all cases the crime had a single female victim. The exact age of the victims was reported in 4 cases7,13,39 (7.7 ± 2.6 years, range 4-10 years), while in 2 cases the victims were only described as being “teenager.”6,40

The victim's relation to the defendant was reported in 5 cases: a daughter (case CJ by Shapiro et al.),7 a partner's daughter,13 a friend of defendant's daughter,40 a friend,41 and a housemate, respectively.38

Circumstantial Factors

In 4 cases, the defendant and the victim were sleeping in the same bed7,39 or in the same room,6 while in 4 cases they were sleeping in different rooms in the same home.13,38,40,41

In the only 3 cases in which the interval between the time of sleep onset of the defendant and the time of the criminal event was reported, it was approximately 1-2 hours.39–41 In 1 case the authors specified that “[the events] usually [occurred] during the first third of the night.”13

Details about the psycho-physical condition of the defendant at the time of the event included exposure to stress,6,7,37,39 sleep deprivation (including Shapiro et al. case CJ),6,7,39 limited,6,37 unspecified,41 or excessive alcohol intake (including Shapiro et al. case AF),7,38,39 either alone or variably associated. In 1 case, the defendant also used marijuana (Shapiro et al. case AF).7

Forensic Evaluation

In 4 cases, the defendant underwent only a neurologic or psychiatric evaluation37–40 (in the case reported by Thomas,37 neuropsychological assessment and PSG were not approved by the court due to limited funds). In 5 cases, PSG41 or video-PSG6,7,13 were performed for forensic purposes, and PSG findings were always provided in detail, apart from the case AF reported by Shapiro et al.7 In 3 cases, additional clinical evaluations were reported, including sleep questionnaires,41 multiple sleep latency test, urine drug screens, EEG, and brain magnetic resonance imaging.6,13

In 2 cases, the number of PSG recordings was specified (341 and 513 nights, respectively), and provocative tests were performed: alcohol challenge (details not reported)41 and sleep restriction (4 hours of sleep on 4 consecutive nights),13 respectively.

The conclusions provided by the experts included sleepwalking in 3 cases37,40,41; NREM parasomnia in 3 cases (including the case AF by Shapiro et al.)6,7,39; nocturnal complex partial seizure in 1 case38; “parasomnic behaviour” in 1 case (case CJ by Shapiro et al.)7; and parasomnia overlap disorder (sleepwalking, SBS, RBD) in 1 case.13

DISCUSSION

From the 1980s, with the advent of formal video-PSG monitoring techniques and the first systematic classification of sleep disorders, the forensic dimension of sleep medicine entered a very new era. Since then, there has emerged a relevant scientific medical literature on this topic. Nevertheless, the sleep defense still “strikes the heart of the criminal law jurisprudence”,51 which reflects the difficulty in evaluating the defendant's level of consciousness and the state of mind and volitional criminal intent. This requires a sleep expert opinion to provide objective and scientific elements supporting (or not) an underlying sleep disorder as the basis for the criminal behavior.

Our review has framed previously published medical-legal cases by means of a detailed analysis of legal issues, the defendant and victim characteristics, the circumstantial factors surrounding the crime, and the forensic evaluation. In order to have an official and international peer-reviewed foundation for establishing the presence of a sleep disorder, we included articles published since 1980, i.e., after the release of the first “Diagnostic classification of sleep and arousal disorders.”28 Cases sufficiently informative about the forensic evaluation (i.e., only half of those retrieved) were published from 1985 to 2011, mainly in journals in the psychiatric field, but also in the fields of legal medicine, sleep medicine, and sexual medicine, thus calling attention to the growing multidisciplinary interest to publish these cases. Unfortunately, the lack of completeness of the remaining published cases prevented an analysis about all the cases that came to trial.

All SRV reports encompassed major crimes (murder or attempted murder), while in SBS cases the criminal charges ranged from sexual touching to rape. In 1 case, the charge of “indecent exposure”37 demonstrates that sleep disorders may result in criminal behavior, even when physical contact between a defendant and the victim is lacking.

In most of the cases, the sleep disorder supporting the sleep defense was sleepwalking, which indicates that the sleep defense generally corresponds to a “sleepwalking defense.” The trial outcome was in favor of the defendant in all SBS and in two-thirds of SRV cases. However, we can not exclude a publication bias due to a possible greater interest engendered by an acquittal than by a conviction. In addition, some verdicts may be challenged on appeal, which could ultimately result in a different outcome for the defendant.

Almost all these legal cases concerned a single criminal episode, and had a single victim. In all cases, defendants were men of relatively young age; this was also found by Bonkalo in 20 cases of homicide collected from 1791 until 1969.26 Beyond medical-legal cases, SRV with moderate to severe injuries is known to be frequently reported in males of relatively young age.52–56

Moreover, based on our results, in most cases defendants had no prior criminal record, were employed, had a partner, and did not demonstrate any antisocial trait. In the context of otherwise unremarkable medical histories, the defendants' sleep history usually disclosed past or ongoing sleepwalking, frequently associated with other parasomnias and characterized by complex sleep behaviors. A family history, when investigated, revealed parasomnia in relatives in almost all cases.

Interestingly, differences between SRV and SBS cases were found in the victims' characteristics. Indeed, in most SRV cases the victim was an adult relative of the defendant, and of female gender in two-thirds of cases, while SBS victims were always females, and in most cases minors without a familial relationship with the defendant. Since it is known from the literature that in SBS cases, bed partners often experience physical injuries (ecchymoses, lacerations),8 our results suggest that the sexual offence is criminally reported only when the defendant is not known/not a relative or when the victim is a minor.

When reported, the time interval between the defendant's sleep onset and the crime was around 1-2 hours, consistent with the presence of a NREM parasomnia in most cases. In accordance with the published literature,27 there was a close physical proximity between the defendant and the victim (sleeping in the same bed, sleeping the same room, sharing the same home) in almost all SRV cases and in all SBS cases.

Alcohol intake by the defendant on the night of the event was reported in 2 of 9 of SRV cases and in 6 of 9 of SBS cases. Despite alcohol intake being previously listed as a “precipitating factor” of confusional arousals, and a “risk factor” for sleepwalking,57 the scientific evidence of alcohol-induced sleepwalking or confusional arousals as a defense to criminal behavior has been reviewed.58,59 The recently published International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD-3)10 highlights the absence of a compelling relationship between alcohol use and a disorder of arousal, stating that, in the presence of alcohol intoxication, disorders of arousals should not be diagnosed. The above position complies with the current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders edition that has removed alcohol from the list of possible triggers for sleepwalking, adding also a section on the differential diagnosis of alcohol blackout.60 These major shifts in opinion have important implications for those forensic cases in which unspecified or excessive amount of alcohol intake was reported.

A sustained or coincidental exposure to stressful condition was often reported, while sleep deprivation and caffeine overuse were pointed out less frequently. All the above mentioned conditions have been reported in literature as potential triggering factors for SRV in sleepwalking and sleep terrors,22,53 and a recent longitudinal survey of 100 sleepwalkers found that those with a history of SRV more frequently reported triggering factors.56

The forensic evaluations differed from case to case for both SRV and SBS. A forensic evaluation restricted to neurological and/or psychiatric assessments, or at most an EEG, was carried out in the older cases, while all cases published after 1998 reported at least a PSG or video-PSG study for 1 to 6 nights, along with neuropsychological tests, brain computerized tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging in some cases. PSG at times was performed under sleep restriction or with sound/ tactile provocation of arousals during the night. In two cases followed by the same author,36,41 a PSG alcohol challenge study was performed, with limited details provided, and without an explicit rationale. In 1 case,34 the Court ordered to replicate the same forensic workup performed in a previous case.31

Our review concludes that in most cases, the advice of a sleep expert is requested in cases of a suspected or purported sleepwalking-related felony.

A consensus about guidelines to follow in the forensic assessment of such cases is still lacking. Nevertheless, there is broad agreement that the sleep expert workup should include at least the following steps:

History of sleep disorders should be carefully investigated in relatives.6,21,35

A complete description of the defendant's lifetime history of any motor behavior during sleep, preferably from both the defendant and possible witnesses (present and former bed partners/relatives/friends) should be obtained, and details about age at onset, the usual timing of the event during the sleep, the degree of amnesia, and both duration and frequency of episodes should be investigated.1,6,21,35,61

Information about sleep/wake habits, drugs (prescribed or illicit), herbal products, and habitual caffeine and alcohol consumption/abuse should be collected.6,35,53

Along with information about the event, circumstantial factors of both the person's life and the hours prior to the episode is essential: stressful events, sleep deprivation or excessive fatigue, and intake of alcohol and other substances should be investigated.6,35,61

Complete physical, neurologic, and psychiatric evaluations along with administration of standardized questionnaires for sleep disorders should be carried out.4,15,20,35,62

A video-PSG study to identify or rule out other sleep disorders associated with abnormal motor behaviors (RBD, nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy) or possibly triggering sleepwalking (OSA, periodic limb movements) should be performed with standard polysomnographic monitoring63 and with an extensive scalp EEG, electromyographic monitoring also of the arms, and time-synchronized audiovisual recording.4,15,20,21 To increase the possibility to capture an event, the documentation of nocturnal episodes with home video using a camera with infrared night vision function could be useful.4,6,62,64 Combining video and PSG monitoring at home may allow for longer recording periods and minimize bias from monitoring in a sleep laboratory setting. However, home video-PSG recording prevents the possibility of technician/physician intervention during and after a parasomnia episode. For these reasons, home video-PSG should be performed, when feasible, in conjunction with a sleep laboratory study.

It should be emphasized in the forensic context that irrespective of whether an event compatible with sleepwalking is recorded during PSG, this will not conclusively indicate that the defendant was or was not sleepwalking at time of the criminal event. Indeed, the only direct evidence of whether or not a criminal act occurred during a state of parasomnia comes from any eyewitness testimony and/or evidence obtained from the scene of the crime. Nevertheless, sleep experts have the duty to pursue as much as possible objective data to support or not support a diagnosis of sleepwalking. Accordingly, they should first evaluate the conditions in which a sleepwalking episode may occur, namely a genetic predisposition in the presence of an increased pressure for slow wave sleep and factors favoring arousals or fragmenting sleep.4

From this perspective, the Montplaisir group's sleep-deprivation protocols65 have been considered by some authors as a “promising novel approach to the forensic use of PSG in sleepwalking cases” for ruling out or greatly minimizing the probability that the accused is in fact a sleepwalker.66 In predisposed individuals, 25-38 hours of sleep deprivation increases the number and the complexity of sleepwalking events recorded in the laboratory during sleep recovery, whereas similar sleep deprivation does not lead to sleep behaviors in subjects with no history of sleepwalking.65,67,68 In addition, several studies have disclosed neurophysiological abnormalities in sleepwalkers' slow wave sleep, even on nights without episodes, namely the absence of NREM sleep continuity, the overall decrease in slow wave activity during the first sleep cycles, and the increased cyclic alternating pattern rate.69–74 Further scientific evidence is needed to establish that these PSG findings are stable neuro-physiological markers of sleepwalking. Therefore, at the present time, they may only provide indirect and circumstantial evidence in courtroom.

Cartwright and Guilleminault have recently reported that a PSG spectral analysis was used during a trial as a basis of an expert witness testimony.75 The reliability of this analysis in a forensic setting has been seriously questioned on the grounds of the lack of sufficient sensitivity, specificity, and stability over the time.76 In particular, according to some studies,77–79 arousals from deep sleep and hypersynchronous delta waves lack sufficient sensitivity and specificity to be used as diagnostic markers.10 In their rebuttal, Cartwright and Guilleminault claimed that several studies make “a low slow wave activity a strong candidate to be a manifestation of the genetic vulnerability to abnormal delta arousals and therefore likely to be a stable characteristic of sleep.”80

Finally, due to the complex nature of SRV and SBS, the opinion of a properly credentialed sleep expert81,82 and a multi-disciplinary approach are highly recommended in forensic cases.16,20

Forensic sleep medicine is at an embryonic stage. Our review points out that many medical-legal cases of SRV and SBS, reported in the form of small case series and case reports, do not provide essential information about a proper forensic evaluation. Cases sufficiently informative offer the conclusion that court trials for SRV and SBS involved relatively young and healthy adult males as the defendants, while victims were usually adult relatives in SRV cases and unrelated teenage or young girls in SBS cases. Although many sleep disorders could result in assaultive behaviors, in most cases sleepwalking was implicated, and the sleepwalking defense turned out to be generally successful. However, no common protocols for the forensic evaluation were utilized.

An international expert consensus among sleep experts, medical-legal experts, and psychiatrists for the forensic evaluation of SRV and SBS cases should be developed, which we consider to be an urgent priority. This report has provided a foundation for advocating such an international consensus.

Finally, enhancing the publication of accurate and comprehensive reports of medical-legal cases involving SRV and SBS would provide essential information for sleep medicine experts who participate in forensic evaluations, and a relatively homogeneous body of data for ongoing scientific research.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Excluded cases

REFERENCES

- 1.Mahowald MW, Schenck CH. Medical-legal aspects of sleep medicine. Neurol Clin. 1999;17:215–34. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohayon MM, Schenck CH. Violent behavior during sleep: prevalence, comorbidity and consequences. Sleep Med. 2010;11:941–6. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plazzi G, Tinuper P, Montagna P, Provini F, Lugaresi E. Epileptic nocturnal wanderings. Sleep. 1995;18:749–56. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.9.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siclari F, Khatami R, Urbaniok F, et al. Violence in sleep. Brain. 2010;133:3494–509. doi: 10.1093/brain/awq296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong KE. Masturbation during sleep–a somnambulistic variant? Singapore Med J. 1986;27:542–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guilleminault C, Moscovitch A, Yuen K, Poyares D. Atypical sexual behavior during sleep. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:328–36. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro CM, Trajanovic NN, Fedoroff JP. Sexsomnia-a new parasomnia? Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:311–7. doi: 10.1177/070674370304800506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schenck CH, Arnulf I, Mahowald MW. Sleep and sex: what can go wrong? A review of the literature on sleep related disorders and abnormal sexual behaviors and experiences. Sleep. 2007;30:683–702. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.6.683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Béjot Y, Juenet N, Garrouty R, et al. Sexsomnia: an uncommon variety of parasomnia. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2010;112:72–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2009.08.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alves R, Alóe F, Tavares S, et al. Sexual behavior in sleep, sleepwalking and possible REM behavior disorder: a case report. Sleep Res Online. 1999;2:71–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Della Marca G, Dittoni S, Frusciante R, et al. Abnormal sexual behavior during sleep. J Sex Med. 2009;6:3490–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cicolin A, Tribolo A, Giordano A, et al. Sexual behaviors during sleep associated with polysomnographically confirmed parasomnia overlap disorder. Sleep Med. 2011;12:523–8. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. Parasomnias associated with sleep-disordered breathing and its therapy, including sexsomnia as a recently recognized parasomnia. Somnology. 2008;12:38–49. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mahowald MW, Bundlie SR, Hurwitz TD, Schenck CH. Sleep violence-forensic science implications: polygraphic and video documentation. J Forensic Sci. 1990;35:413–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahowald MW, Schenck CH, Rosen GM, Hurwitz TD. The role of a sleep disorder center in evaluating sleep violence. Arch Neurol. 1992;49:604–7. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1992.00530300036007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fenwick P. Sleep and sexual offending. Med Sci Law. 1996;36:122–34. doi: 10.1177/002580249603600207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahowald MW, Schenck CH. Parasomnias: sleepwalking and the law. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4:321–39. doi: 10.1053/smrv.1999.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahowald MW, Schenck CH, Cramer Bornemann MA. Sleep-related violence. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2005;5:153–8. doi: 10.1007/s11910-005-0014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bornemann MA, Mahowald MW, Schenck CH. Parasomnias: clinical features and forensic implications. Chest. 2006;130:605–10. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersen ML, Poyares D, Alves RS, Skomro R, Tufik S. Sexsomnia: abnormal sexual behavior during sleep. Brain Res Rev. 2007;56:271–82. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pressman MR. Factors that predispose, prime and precipitate NREM parasomnias in adults: clinical and forensic implications. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:5–30. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schenck CH, Lee SA, Bornemann MA, Mahowald MW. Potentially lethal behaviors associated with rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: review of the literature and forensic implications. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54:1475–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2009.01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrison I, Rumbold JM, Riha RL. Medicolegal aspects of complex behaviours arising from the sleep period: A review and guide for the practising sleep physician. Sleep Med Rev. 2014;18:229–40. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delgado-Rodrigues RN, Allen AN, Galuzzi dos Santos L, Schenck CH. Sleep Forensics-A Critical review of the literature and brief comments on the Brazilian legal situation. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2014;72:164–9. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20130181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonkalo A. Impulsive acts and confusional states during incomplete arousal from sleep: crinimological and forensic implications. Psychiatr Q. 1974;48:400–9. doi: 10.1007/BF01562162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pressman MR. Disorders of arousal from sleep and violent behavior: the role of physical contact and proximity. Sleep. 2007;30:1039–47. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.8.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Association of Sleep Disorders Centers and the Association for the Psychophysiological Study of Sleep. Diagnostic classification of sleep and arousal disorders. Sleep. 1979;2:1–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oswald I, Evans J. On serious violence during sleep-walking. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:688–91. doi: 10.1192/bjp.147.6.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard C, D'Orbán PT. Violence in sleep: medico-legal issues and two case reports. Psychol Med. 1987;17:915–25. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700000726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Broughton R, Billings R, Cartwright R, et al. Homicidal somnambulism: a case report. Sleep. 1994;17:253–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nofzinger EA, Wettstein RM. Homicidal behavior and sleep apnea: a case report and medicolegal discussion. Sleep. 1995;18:776–82. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.9.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kayumov L, Pandi-Perumal SR, Fedoroff P, Shapiro CM. Diagnostic values of polysomnography in forensic medicine. J Forensic Sci. 2000;45:191–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cartwright R. Sleepwalking violence: a sleep disorder, a legal dilemma, and a psychological challenge. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1149–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poyares D, Almeida CM, Silva RS, Rosa A, Guilleminault C. Violent behavior during sleep. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2005;27:22–6. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462005000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ebrahim IO, Fenwick P. Sleep-related automatism and the law. Med Sci Law. 2008;48:124–36. doi: 10.1258/rsmmsl.48.2.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas TN. Sleepwalking disorder and mens rea: a review and case report. J Forensic Sci. 1997;42:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borum R, Appelbaum KL. Epilepsy, aggression, and criminal responsibility. Psychiatr Serv. 1996;47:762–3. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.7.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. An analysis of a recent criminal trial involving sexual misconduct with a child, alcohol abuse and a successful sleepwalking defence: arguments supporting two proposed new forensic categories. Med Sci Law. 1998;38:147–52. doi: 10.1177/002580249803800211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rosenfeld DS, Elhajjar AJ. Sleepsex: a variant of sleepwalking. Arch Sex Behav. 1998;27:269–78. doi: 10.1023/a:1018651018224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ebrahim IO. Somnambulistic sexual behaviour (sexsomnia) J Clin Forensic Med. 2006;13:219–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jcfm.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Buchanan A. Sleepwalking and indecent exposure. Med Sci Law. 1991;31:38–40. doi: 10.1177/002580249103100107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Samuels A, O'Driscoll C, Allnutt S. When killing isn't murder: psychiatric and psychological defences to murder when the insanity defence is not applicable. Australas Psychiatry. 2007;15:474–9. doi: 10.1080/10398560701616239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bornemann MA. Role of the expert witness in sleep-related violence trials. Virtual Mentor. 2008;10:571–7. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2008.10.9.hlaw1-0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohanty K. Transmission of Chlamydia and genital warts during sleepwalking. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:129–30. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bordenave FJ, Kelly DC. Not guilty by reason of somnambulism. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2009;37:571–73. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Beach CA, Soliman S. Reliability of sleep parasomnia and the trustworthiness of patient self-reporting. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law Online. 2010;38:601–3. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ingravallo F, Schenck CH, Plazzi G. Injurious REM sleep behaviour disorder in narcolepsy with cataplexy contributing to criminal proceedings and divorce. Sleep Med. 2010;11:950–2. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wortzel HS, Strom LA, Anderson AC, Maa EH, Spitz M. Disrobing associated with epileptic seizures and forensic implications. J Forensic Sci. 2012;57:550–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2011.01995.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vlahos J. The case of the sleeping slayer. Sci Am. 2012;307:48–53. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0912-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horne M. A rude awakening: what to do with the sleepwalking defense? Boston Coll Law Rev. 2004;46:149–82. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schenck CH, Milner DM, Hurwitz TD, Bundlie SR, Mahowald MW. A polysomnographic and clinical report on sleep-related injury in 100 adult patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146:1166–73. doi: 10.1176/ajp.146.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moldofsky H, Gilbert R, Lue FA, MacLean AW. Sleep-related violence. Sleep. 1995;18:731–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.9.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Priest RG. Violent behavior during sleep. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58:369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guilleminault C, Leger D, Philip P, Ohayon MM. Nocturnal wandering and violence: review of a sleep clinic population. J Forensic Sci. 1998;43:158–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lopez R, Jaussent I, Scholz S, Bayard S, Montplaisir J, Dauvilliers Y. Functional impairment in adult sleepwalkers: a case-control study. Sleep. 2013;36:345–51. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd ed: Diagnostic and coding manual. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pressman MR, Mahowald MW, Schenck CH, Bornemann MC. Alcohol-induced sleepwalking or confusional arousal as a defense to criminal behavior: a review of scientific evidence, methods and forensic considerations. J Sleep Res. 2007;16:198–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cramer Bornemann MA, Mahowald MW. Sleep forensics. In: Kryger MH, Roth C, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. pp. 725–33. [Google Scholar]

- 60.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cartwright R. Sleep-related violence: does the polysomnogram help establish the diagnosis? Sleep Med. 2000;1:331–5. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Broughton RJ, Shimizu T. Sleep-related violence: a medical and forensic challenge. Sleep. 1995;18:727–30. doi: 10.1093/sleep/18.9.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, Quan SF. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. 1st ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nobili L. Can homemade video recording become more than a screening tool? Sleep. 2009;32:1544–5. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.12.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Joncas S, Zadra A, Paquet J, Montplaisir J. The value of sleep deprivation as a diagnostic tool in adult sleepwalkers. Neurology. 2002;58:936–40. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.6.936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mahowald MW, Schenck CH, Cramer-Bornemann M. Finally-sleep science for the courtroom. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zadra A, Pilon M, Montplaisir J. Polysomnographic diagnosis of sleepwalking: effects of sleep deprivation. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:513–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.21339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pilon M, Montplaisir J, Zadra A. Precipitating factors of somnambulism: impact of sleep deprivation and forced arousals. Neurology. 2008;70:2284–90. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304082.49839.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zucconi M, Oldani A, Ferini-Strambi L, Smirne S. Arousal fluctuations in non-rapid eye movement parasomnias: the role of cyclic alternating pattern as a measure of sleep instability. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1995;12:147–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gaudreau H, Joncas S, Zadra A, Montplaisir J. Dynamics of slow-wave activity during the NREM sleep of sleepwalkers and control subjects. Sleep. 2000;23:755–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Espa F, Ondze B, Deglise P, Billiard M, Besset A. Sleep architecture, slow wave activity, and sleep spindles in adult patients with sleepwalking and sleep terrors. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111:929–39. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(00)00249-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guilleminault C, Poyares D, Aftab FA, Palombini L. Sleep and wakefulness in somnambulism: a spectral analysis study. J Psychosom Res. 2001;51:411–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Guilleminault C. Hypersynchronous slow delta, cyclic alternating pattern and sleepwalking. Sleep. 2006;29:14–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guilleminault C, Kirisoglu C, da Rosa AC, Lopes C, Chan A. Sleepwalking, a disorder of NREM sleep instability. Sleep Med. 2006;7:163–70. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cartwright RD, Guilleminault C. Defending sleepwalkers with science and an illustrative case. J Clin Sleep Med. 2013;9:721–6. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pressman MR, Mahowald M, Schenck C, et al. Spectral EEG analysis and sleepwalking defense: unreliable scientific evidence. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10:111–2. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brozman B, Foldvary NR, Dinner D, Loddenkemmper T, Lim L, Golish J. The value of the unexplained polysomnographic arousals from slow-wave sleep in predicting sleepwalking and sleep terrors in a sleep laboratory patient population. Sleep. 2003;26:A325. (Abstract Suppl) [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pressman MR. Hypersynchronous delta sleep EEG activity and sudden arousals from slow wave sleep in adults without a history of parasomnias: clinical and forensic implications. Sleep. 2004;27:706–10. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.4.706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pilon M, Zadra A, Joncas S, Montplaisir J. Hypersynchronous delta waves and somnambulism: brain topography and effect of sleep deprivation. Sleep. 2006;29:77–84. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cartwright R, Guilleminault C. Slow wave activity is reliably low in sleepwalkers: response to Pressman et al. letter to the editor. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;15:113–5. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) AASM Standards for Accreditation of Sleep Disorders Centers. 2013. [accessed on April 2, 2014]. Available at: http://www.aasmnet.org/Resources/PDF/AASMcenteraccredstandards.pdf.

- 82.Pevernagie D, Stanley N, Berg S, et al. European guidelines for the certification of professionals in sleep medicine: report of the task force of the European Sleep Research Society. J Sleep Res. 2009;18:136–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Excluded cases