Abstract

Sequence homology predicts that the extracellular domain of the sodium channel β1 subunit forms an immunoglobulin (Ig) fold and functions as a cell adhesion molecule. We show here that β1 subunits associate with neurofascin, a neuronal cell adhesion molecule that plays a key role in the assembly of nodes of Ranvier. The first Ig-like domain and second fibronectin type III–like domain of neurofascin mediate the interaction with the extracellular Ig-like domain of β1, confirming the proposed function of this domain as a cell adhesion molecule. β1 subunits localize to nodes of Ranvier with neurofascin in sciatic nerve axons, and β1 and neurofascin are associated as early as postnatal day 5, during the period that nodes of Ranvier are forming. This association of β1 subunit extracellular domains with neurofascin in developing axons may facilitate recruitment and concentration of sodium channel complexes at nodes of Ranvier.

Keywords: sodium channel; neurofascin; neural cell adhesion molecules; nodes of Ranvier; protein binding

Introduction

Neuronal voltage-gated sodium channels are composed of three subunits: a large pore-forming α subunit (260 kD) and two smaller auxiliary β subunits, β1 (36 kD) and β2 (33 kD) (Catterall, 1992; Isom et al., 1992, 1995). A third β subunit named β3, which shares 57% identity with β1, has been cloned recently (Curtis, R.A., D. Lawson, P. Ge, P.S. DiStefano, and I. Solis-Santiago. 2000. Cloning and localization of a novel Na+ channel β3 subunit. Society of Neuroscience Annual Meeting. 418.22 [Abstr.]; Morgan et al., 2000). The extracellular domains of all β subunits are predicted to form V-type Ig-like folds, and it is proposed that these domains have cell adhesion properties (Isom et al., 1995; Isom and Catterall, 1996). Clustering of sodium channels along myelinated axons at nodes of Ranvier is essential for efficient conduction of action potentials. This concentration of sodium channels at nodes of Ranvier is believed to involve interactions with glial cells, the extracellular matrix, and the cytoskeleton (Salzer, 1997). The 480- and 270-kD isoforms of the cytoskeletal spectrin-binding protein ankyrinG are highly concentrated at nodes (Kordeli et al., 1995; Zhou et al., 1998), and have been copurified with sodium channels from rat brain membrane preparations (Srinivasan et al., 1988). This interaction may be mediated by the intracellular domains of β1 and β2, which have been shown to recruit ankyrin (Malhotra et al., 2000). The neuronal extracellular matrix protein tenascin R, which localizes to nodes of Ranvier, has been shown to bind the β2 subunit of sodium channels (Srinivasan et al., 1998; Xiao et al., 1999) and the cell adhesion molecule (CAM)* neurofascin (Volkmer et al., 1998), suggesting a functional relationship among these molecular components. As the extracellular domains of sodium channel β subunits are homologous to CAMs belonging to the Ig superfamily, we predicted that they might interact with other neuronal CAMs in close proximity.

Neurofascin belongs to the L1 family of neuronal CAMs containing extracellular Ig- and fibronectin (FN) type III–like domains, as well as ankyrin binding activity in their cytoplasmic domains (see Fig. 1 A). FIGQY, a highly conserved sequence in L1 family intracellular domains, is required for ankyrin binding, and phosphorylation of the FIGQY tyrosine residue abolishes binding (Garver et al., 1997). Neurofascin and another L1 family member, NrCAM, become clustered along rat sciatic nerve axons early during postnatal development, thus defining the sites for assembly of nodes of Ranvier (Davis et al., 1996). AnkyrinG and sodium channels are subsequently recruited to these sites as nodes mature (Lambert et al., 1997). Sodium channel α and β subunits also assemble during this developmental period (Wollner et al., 1988). There are several splice variants of neurofascin, including a 155- and a 186-kD isoform (Davis et al., 1996). The 155-kD isoform contains six extracellular Ig domains followed by four FN domains, whereas the third FN domain is absent from the 186-kD isoform, and a mucin-like domain is inserted after FN domain 4. Only the 186-kD isoform, neurofascin 186, appears to be localized to nodes of Ranvier, whereas the 155-kD isoform is expressed only in unmyelinated fibers (Davis et al., 1996). Neurofascin 186 is also localized to Purkinje cell axon initial segments, whereas the 155-kD isoform is expressed in cell bodies and dendrites (Davis et al., 1996).

Figure 1.

Sodium channel β1 and β3 subunits coimmunoprecipitate with neurofascin in cotransfected tsA-201 cells. (A) Representation of HA.11-tagged neurofascin 186. (B) TsA-201 cells were cotransfected with neurofascin 186 (NF186) and sodium channel subunits as indicated. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies and the blot was probed with monoclonal antibody anti-HA.11. Each cell lysate was probed with anti-HA.11 or specific antisodium channel antibodies as shown to confirm that all proteins were expressed (bottom).

We show here that sodium channel β1 subunits interact with neurofascin early in development and remain associated in adult rat brain. Only sodium channel β1 and β3 subunits are able to interact with neurofascin, and this interaction involves their extracellular domains. β1 subunits localize to nodes of Ranvier in rat sciatic nerve with neurofascin. Together, these data suggest that the association of β1 or β3 subunit extracellular domains with neurofascin is involved in targeting sodium channels to nodes of Ranvier in developing axons and retaining channels at nodes in mature myelinated axons.

Results and discussion

Neurofascin interacts with β1 and β3 subunits in cotransfected tsA-201 cells

Neurofascin (Fig. 1 A) and sodium channels exist in close proximity at nodes of Ranvier (Davis et al., 1996). To determine if sodium channel subunits are involved in forming a complex with neurofascin 186, Nav1.2a α subunits plus β1, β2, or β3 subunits were expressed separately in tsA-201 cells with neurofascin 186. As no β3 antibody was available, β3 was fused to a c-myc epitope tag at its COOH terminus. Neurofascin 186 was fused to a hemagglutinin (HA) epitope (HA.11) tag at its NH2 terminus for detection in transfected cells. 40 h after transfection, cells were lysed and their proteins immunoprecipitated using subunit-specific polyclonal antibodies anti-SP20, anti-β1CT, and anti-β2CT, and monoclonal antibody anti-myc, respectively. Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Blots were probed with monoclonal anti-HA.11 antibody, which detected coimmunoprecipitation of neurofascin 186 with β1 and homologous β3 subunits only (Fig. 1 B). Immunoblotting of cell lysates demonstrated robust expression of all subunits in cells cotransfected with neurofascin 186 and α or β2 subunits. Removal of the HA.11 tag from neurofascin 186 did not affect its interaction with β1 (unpublished data).

β1 and β3 mRNAs are both found in central and peripheral neurons, with overlapping as well as distinct patterns of expression (Curtis, R.A., D. Lawson, P. Ge, P.S. DiStefano, and I. Solis-Santiago. 2000. Cloning and localization of a novel Na+/− channel β3 subunit. Society of Neuroscience Annual Meeting. 418.22 [Abstr.]; Morgan et al., 2000; unpublished data), suggesting that β1 and β3 play similar roles. This concept is supported by the ability of both subunits to associate with neurofascin, whereas β2, which shares less homology with β1 and β3, does not interact with neurofascin. β2 subunits share homology with contactin/F3/F11 (Isom et al., 1995), a glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored CAM that interacts with NrCAM (Morales et al., 1993; Sakurai et al., 1997). It will be interesting to investigate whether β2 subunits are able to interact with NrCAM at nodes of Ranvier, thus providing a further mechanism by which sodium channels are targeted to these specialized regions.

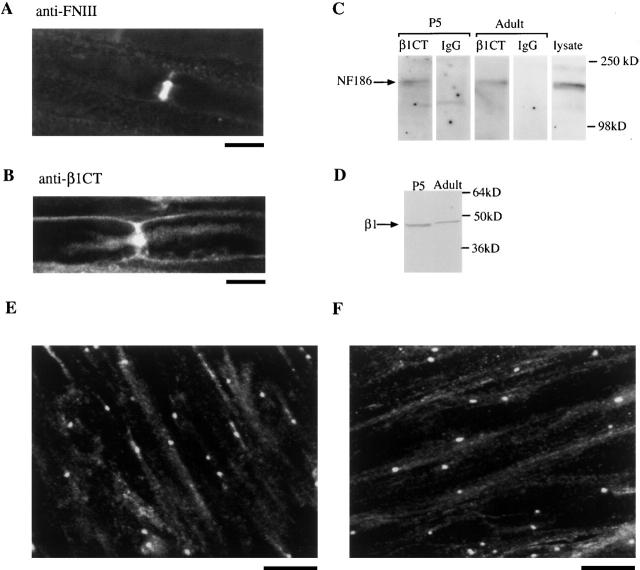

Neurofascin and β1 localize to nodes of Ranvier and associate in rat brain

Sodium channel α subunits have been shown to localize to nodes of Ranvier (Ellisman and Levinson, 1982; Vabnick et al., 1996; Rasband et al., 1999), but concentration of β1 subunits at nodes has not been confirmed. The localization of both neurofascin and β1 subunits in sciatic nerve was determined by probing tissue from adult rats with polyclonal anti–FN domain antibody and anti-β1CT, respectively. Neurofascin has previously been localized to nodes of Ranvier in adult rats (Davis et al., 1996), and we confirmed these data for the sciatic nerve (Fig. 2 A) while demonstrating that β1 subunits also localize to highly concentrated sites that appear identical to those stained by anti-FN antibodies (Fig. 2 B). This result shows that both β1 subunits and neurofascin are highly concentrated at nodes of Ranvier.

Figure 2.

Neurofascin and β1 localize to nodes of Ranvier and associate in rat brain. Rat sciatic nerve was labeled with neurofascin antibody anti-FNIII (A) or anti-β1CT (B). Expression of both β1 and neurofascin is concentrated at nodes of Ranvier. (C) P5 or adult rat brain lysates were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies. Blots were probed with neurofascin antimucin antibody. (D) Expression of β1 in both P5 and adult rat brain lysates. (E and F) Teased sciatic nerve stained with anti-β1extra from 3-d-old (E) and 10-d-old (F) rats, demonstrating the localization of β1 at the nodes of Ranvier in development. NF, neurofascin. Bars: 2 μm (A and B) and 10 μm (E and F).

In developing nodes of Ranvier, β1 subunits are localized in the sciatic nerve at postnatal days 3 and 10, during the process of myelination and maturation of the nodes (Fig. 2, E and F). Neurofascin is also localized at developing nodes of Ranvier at these ages (unpublished data; Lambert et al., 1997). Therefore, these two molecules are appropriately positioned to interact with each other as sodium channels are clustered and immobilized in developing nodes of Ranvier.

Neurofascin and NrCAM cluster at nodes of Ranvier in rat sciatic nerve between postnatal days 2 and 5, followed by the recruitment of ankyrinG and sodium channels to these sites (Lambert et al., 1997). To examine whether β1 subunits form a complex with neurofascin from early postnatal development through to adulthood, both P5 and adult rat brain lysates were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal β1 antibody, anti-β1CT, or control rabbit IgG. After SDS-PAGE of immunoprecipitated proteins and immunoblotting, polyclonal antimucin domain antibody detected the 186-kD neurofascin isoform coimmunoprecipitating with β1 subunits in both P5 and adult brain lysates (Fig. 2 C). The antimucin domain antibody was raised against the mucin domain present only in the neurofascin isoform detected at nodes. P5 and adult rat brain lysates were probed with anti-β1CT to confirm that β1 is expressed during early postnatal development (Fig. 2 D).

These results show that β1 subunits interact with neurofascin in developing rat brain, and we propose that this association is involved in targeting sodium channels to specialized regions of the neuron such as nodes of Ranvier and axon initial segments. Previous reports suggest that mature nodes of Ranvier contain sodium channels, neurofascin, and NrCAM, bound in a complex by ankyrinG (Davis et al., 1996; Volkmer et al., 1996; Zhou et al., 1998) that is able to interact with several transmembrane molecules. AnkyrinG is likely to be present in our immunoprecipitates as well, but the experiments presented below show that sodium channels and neurofascin interact through their extracellular domains, so it is unlikely that ankyrinG is required for formation of the complex. Our data show that sodium channel β1 subunits can interact directly with neurofascin in transfected cells and are associated with neurofascin in postnatal and adult rat brain, indicating that this interaction may be involved in both forming the nascent node of Ranvier and stabilizing the mature node.

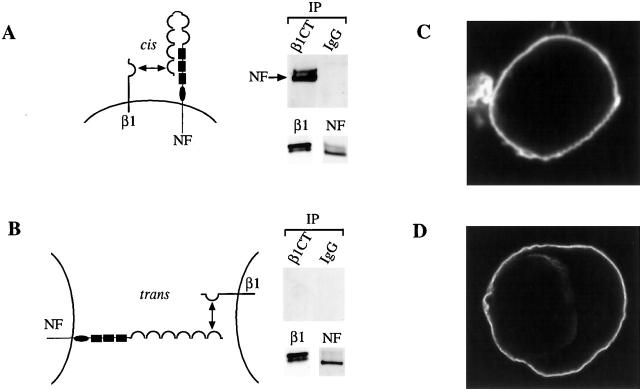

Neurofascin and β1 interact in cis in transfected tsA-201 cells

Both neurofascin and NrCAM form trans-interactions with molecules on adjacent cells (Volkmer et al., 1996). To investigate whether β1 interacts with neurofascin in cis or in trans, tsA-201 cells were transfected together or separately with neurofascin 186 and β1. 20 h after transfection cells were removed from culture dishes by treatment with EDTA, and the separately transfected β1-expressing cells were mixed thoroughly with neurofascin-expressing cells and cultured for a further 24 h to 80% confluency. Cells were lysed and their proteins were immunoprecipitated with anti-β1CT. SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with monoclonal antibody anti-HA.11 detected interaction of β1 and neurofascin in cis (Fig. 3 A), but were unable to detect any neurofascin 186 coimmunoprecipitating with β1 subunits in trans following separate transfection (Fig. 3 B). Immunoblotting of cell lysates showed that both β1 and neurofascin 186 were well expressed (Fig. 3 B). As a control, transfected cells were fixed and stained with anti-β1CT (Fig. 3 C) or anti-HA.11 antibody to tagged neurofascin (Fig. 3 D). Both proteins localized to the plasma membrane, which would allow trans-heterophilic interactions to occur between them. Thus, our results in tsA-201 cells demonstrate that interaction of β1 and neurofascin only occurs in cis within the same cell membrane in this experimental system. This type of interaction would be important in the formation of sodium channel clusters and targeting to nodes of Ranvier in the axonal membrane. However, it is possible that weaker trans-interactions occur between β1 and neurofascin expressed on opposing cells such as the axon and perinodal astrocyte or Schwann cell microvilli. Such trans-interactions may be easily disrupted during cell lysis, and therefore are not detected in our immunoprecipitation experiments.

Figure 3.

β1 and neurofascin associate in cis but not in trans. (A) TsA-201 cells cotransfected with β1 and neurofascin (NF) were lysed and immunoprecipitated (IP) as described previously. (B) TsA-201 cells were transfected separately and cocultured. Lysed cells were immunoprecipitated with the indicated antibodies and the blot was probed with anti-HA.11. The bottom panel shows cell lysates probed with anti-β1CT or anti-HA.11 to demonstrate that proteins were well expressed. (C) Cells transfected with β1 were stained with anti-β1CT, and (D) cells transfected with HA-tagged neurofascin 186 were stained with anti-HA.11.

The β1 extracellular domain is sufficient for association with neurofascin

The intracellular domain of neurofascin 186 interacts with ankyrinG (Zhang et al., 1998), and it has recently been suggested that β1 and β2 subunits may also interact with ankyrin (Malhotra et al., 2000). That study shows that ankyrin is concentrated at points of cell contact in aggregates formed by cells expressing full-length β1 and β2 subunits, but that this concentration is not detected when cells are transfected with β subunits lacking their intracellular domains. This observation suggests that β1 and β2 intracellular domains are able to interact directly or indirectly with ankyrin. An isoform of ankyrin is expressed in the HEK293 cell line from which tsA-201 cells are derived (Zhang et al., 1998), but we were unable to detect either ankyrinB or ankyrinG expression in tsA-201 cells (unpublished data). To investigate whether the presence of an ankyrin isoform in tsA-201 cells mediates the interaction between β1 and neurofascin 186, the intracellular domain of neurofascin 186 was deleted from E1129, thus removing the ankyrin binding site. It has been demonstrated that this mutant is unable to associate with ankyrinG in transfected cell lines (Zhang et al., 1998). TsA-201 cells transfected with this mutant (NF186Δic) and β1 were lysed, and cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with polyclonal antibody β1CT or control IgG. After resolution of proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to nitrocellulose, probing blots with monoclonal antibody anti-HA.11 showed that NF186Δic is able to interact with β1 (Fig. 4 A). These results indicate that ankyrin is not necessary for the formation of this complex.

Figure 4.

The extracellular domain of β1 interacts with neurofascin. (A) TsA-201 cells cotransfected with NF186Δic and β1 were lysed and probed with the indicated antibodies. Blots were probed with anti-HA.11. Cell lysates were also probed with anti-HA.11 and anti-β1CT to show that both proteins were expressed. (B) Cells cotransfected with neurofascin and β1β2β2 were lysed and immunoprecipitated (IP) with the indicated antibody. Blots were probed with anti-HA.11. Cell lysates were probed with anti-HA.11 and anti-β2CT to show expression of both proteins. (C) Cells cotransfected with β1ec–GPI and neurofascin were lysed and immunoprecipitated with antibodies as indicated. Cell lysates were probed with anti-HA.11 or anti-β1extra to show both proteins were expressed.

β subunit extracellular domains were previously proposed to mediate adhesion through interaction with other CAMs (Isom and Catterall, 1996). As the β2 subunit does not interact with neurofascin 186, a chimera between β1 and β2 was used to locate the site of interaction of β1 with neurofascin 186. TsA-201 cells were cotransfected with neurofascin 186 and a β1β2β2 chimera consisting of β2 intracellular and transmembrane domains fused to the β1 extracellular domain. Cells coexpressing neurofascin 186 with β1β2β2 were lysed and immunoprecipitated with anti-β2CT. Immunoprecipitated proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose. Blots probed with the anti-HA.11 antibody showed neurofascin 186 coimmunoprecipitating with β1β2β2 (Fig. 4 B). This result suggests that the extracellular domain of β1 is sufficient for the interaction with neurofascin 186. To confirm this observation, tsA-201 cells were cotransfected with neurofascin 186 and a GPI-linked β1 extracellular domain protein, β1ec–GPI. This fusion protein consists of the β1 extracellular domain, immediately followed by the GPI anchor recognition sequence from human placental alkaline phosphatase (McCormick et al., 1999). The majority of this recognition sequence is cleaved from the protein upon attachment of the GPI moiety. Cells coexpressing β1ec–GPI and neurofascin 186 were lysed and immunoprecipitated using polyclonal antibody anti-β1extra raised against the extracellular domain of β1. After SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting, β1ec–GPI was found to associate with neurofascin 186 (Fig. 4 C), confirming that the β1 extracellular domain alone is sufficient for this interaction. Heterologous expression of β1 or β2 subunits in Drosophila S2 cells induces aggregation, which is proposed to occur through homophilic interactions between the extracellular domains of the β subunits (Malhotra et al., 2000). Our data demonstrate that β1 subunit extracellular domains can also associate heterophilically with another CAM.

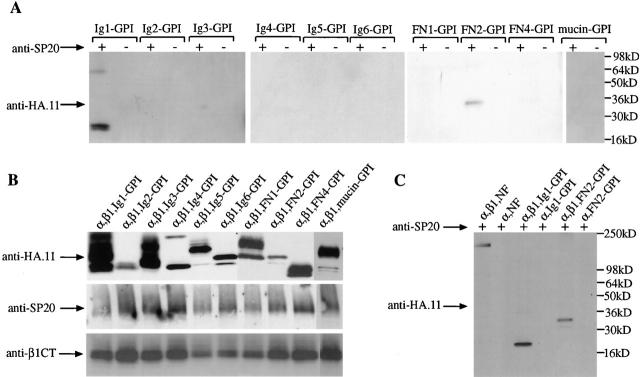

Determination of the neurofascin binding site

The extracellular region of neurofascin 186 consists of multiple domains. To investigate which extracellular domains of neurofascin were able to interact with β1, the Ig domains Ig1–6, the FN domains FN1, 2, and 4, and the mucin-like domain were expressed separately, fused at the NH2 terminus to the HA.11 tag, and at the COOH terminus to the GPI anchor sequence from human placental alkaline phosphatase. These constructs were coexpressed with sodium channel α and β1 subunits in tsA-201 cells. After immunoprecipitation with anti-SP20, only Ig1–GPI and FN2–GPI were able to associate with α/β1 complexes in tsA-201 cells, suggesting that the neurofascin binding site is assembled from amino acids in both of these domains (Fig. 5 A). It was necessary to express β1 complexed with α subunits in these experiments, as the GPI constructs were expressed at high levels and all of them bound nonspecifically to β1 in the absence of α subunits. When α subunits were expressed alone with Ig1–GPI or FN2–GPI no interaction was observed, confirming that this association is β1 dependent (Fig. 5 C). Both the 155- and 186-kD isoforms of neurofascin contain Ig1 and FN2, so β1 should interact with both isoforms. However, β1 is localized to nodes of Ranvier in sciatic nerve and is most likely to interact with neurofascin 186, which also concentrates at nodes. The interaction of Ig1 with β1 in cis suggests that the neurofascin molecule folds back on itself to make this domain accessible to β1, as drawn in Fig. 3 A; thus, binding of amino acids on Ig1 and FN2 with β1 could then occur. It is also possible that the FN2 domain of neurofascin could interact with β1 subunits in a cis configuration, whereas Ig1 interacts with β1 subunits at lower affinity in trans on an opposing membrane. Development of new methods to measure lower-affinity trans-interactions of β1 will be required to test this idea. Similar interactions are made by axonin 1/TAG-1–like glycoproteins, a family of neural CAMs containing six Ig domains and four FN domains. Homophilic trans-interactions occur between Ig domains 2 and 3 of axonin 1 (Freigang et al., 2000), whereas the FN domains of TAX-1, the human homologue of axonin 1, are thought to form cis-homophilic interactions (Tsiotra et al., 1996).

Figure 5.

Determination of the neurofascin binding site. (A) TsA-201 cells were cotransfected with α and β1 subunits and GPI-tagged constructs Ig1-GPI, Ig2-GPI, Ig3-GPI, Ig4-GPI, Ig5-GPI, Ig6-GPI, FN1-GPI, FN2-GPI, FN4-GPI, and mucin-GPI, respectively. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-SP20 and blots were probed with anti-HA.11 antibody. (B) Lysates were probed with anti-SP20, anti-β1CT, and anti-HA.11 to demonstrate that all proteins were expressed. (C) TsA-201 cells were cotransfected with (lane 1) α, β1, and neurofascin 186; (lane 2) α and neurofascin 186; (lane 3) α, β1, and Ig1-GPI; (lane 4) α and Ig1-GPI; (lane 5) α, β1, and FN2-GPI; and (lane 6) α and FN2-GPI. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-SP20 and blots were probed with anti-HA.11 antibody.

These results demonstrate that the extracellular domain of β1 functions as a CAM by adhering to neurofascin. Neurofascin and NrCAM clusters appear along sciatic nerve axons at postnatal day 2, followed by recruitment of ankyrinG and sodium channels (Lambert et al., 1997). Sodium channel recruitment appears to be dependent on ankyrinG, as sodium channels are no longer present at axon initial segments in the granule cells of ankyrinG-null mice, and Purkinje cells show reduced ability to fire action potentials (Zhou et al., 1998). Therefore, neurofascin and NrCAM may initially recruit ankyrinG, and sodium channels may subsequently be targeted to these sites by the interactions between the extracellular domain of β1 and neurofascin, and the intracellular domains of β1 and β2 with ankyrinG. We show that β1 subunits interact with neurofascin in developing rat brain, and propose that this association is involved in targeting sodium channels to specialized regions of the neuron such as nodes of Ranvier and axon initial segments.

Neurofascin and NrCAM are only able to associate with ankyrinG when the conserved tyrosine residue within the FIGQY sequence is dephosphorylated (Garver et al., 1997). We reported recently that sodium channels associate with receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase β (RPTPβ) in developing rat brain (Ratcliffe et al., 2000). This interaction is mediated through the extracellular domain of the α subunit, and the intracellular domains of both the α and β1 subunit; it is observed in neonatal tissue, but is absent at postnatal day 16. RPTPβ is expressed predominantly in glia, but RPTPβ mRNAs have also been detected in neurons (Snyder et al., 1996). The close localization of neurofascin and NrCAM to RPTPβ suggests that they could be substrates, with dephosphorylation occurring early in postnatal development, thus allowing interactions with ankyrinG to occur. As expression of RPTPβ is restricted to the brain (Levy et al., 1993), a related tyrosine phosphatase may perform a similar function in the peripheral nervous system.

Materials and methods

Antibodies and DNA constructs

Polyclonal antibodies anti-β1CT and anti-β2CT raised against the COOH termini of β1 and β2, respectively, and sodium channel α subunit antibody anti-SP20 were prepared as described previously (Ratcliffe et al., 2000). Polyclonal antimucin domain antibody raised against the mucin domain of neurofascin 186, and anti-FN domain antibody raised against all four FN domains of neurofascin, were gifts from Dr. Vann Bennett (Duke University, Durham, NC) (Davis et al., 1996). Polyclonal antibody anti-β1extra was a gift from Dr. Lori Isom (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI) (Xiao et al., 1999). Monoclonal antibody anti-HA.11 was purchased from Covance Research Products, Inc., and monoclonal anti-myc antibody was purchased from Invitrogen.

Sodium channel subunit mammalian expression plasmids pCDM8α (encoding Nav1.2a), pCDM8β1, pCDM8β2, and chimera pCDM8β1β2β2 have been described previously (Auld et al., 1990; Ratcliffe et al., 2000). β3 cDNA was amplified and subcloned into pcDNA3.1myc-his (Invitrogen) for expression of tagged β3. β1ec–GPI was subcloned from pSP64T (McCormick et al., 1999) into pCDM8. cDNA encoding neurofascin 186 tagged at the NH2 terminus with HA.11 was provided by Dr. Vann Bennett. This cDNA was subcloned into the EcoRI site of pcDNA3.1 (Invitrogen). pcDNA3.1NF186Δic was constructed by introducing a stop codon after residue E1129. Neurofascin 186 GPI-tagged constructs were made as follows. A Cla1 restriction site was introduced into pcDNA3.1NF186 through a silent change of the codon for S8 from AGC to TCG. The ClaI-EcoRV fragment of pcDNA3.1NF186, which includes all but the first eight amino acids of neurofascin 186 and the HA.11 tag, was removed and replaced with a PCR product encompassing the mucin domain, amino acids P897–A1084. The GPI anchor recognition sequence from human placental alkaline phosphatase (McCormick et al., 1999) was then cloned in frame into the EcoRV-XhoI sites of this construct to produce pcDNA3.1mucin-GPI. For construction of remaining GPI-tagged domain expression vectors, the ClaI-EcoRV fragment of pcDNA3.1mucin-GPI was replaced with PCR products coding for Ig1 (P16-Q11), Ig2 (V112-T212), Ig3 (R213-P313), Ig4 (Y314-P406), Ig5 (R407-T498), Ig6 (R499-L586), FN1 (A587-P703), FN2 (E704-L801), and FN4 (P802-A905).

Coimmunoprecipitation experiments

Membrane fractions were prepared from P5 and adult rat brains as described previously (Nishiwaki et al., 1998). For immunoprecipitation reactions, 500 μg of total protein was added to 20 μg of anti-β1CT or control IgG antibody, and incubated for 2 h at 4°C. Protein A–agarose was added, and the incubation was continued overnight. The complex bound to the agarose beads, was washed extensively, and bound proteins were heat eluted in SDS loading buffer at 100°C for 10 min. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose, and neurofascin 186 was detected using polyclonal antimucin domain antibody. For coimmunoprecipitation assays performed using tsA-201 cell lysates, 50 μg of an equimolar ratio of expression plasmids was transfected into cells in DMEM F12 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and streptomycin plated on 150-mm dishes using the calcium phosphate method. At 40 h after transfection, cell monolayers were washed in PBS, lysed in 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 15 mM NaCl, 1 mM EGTA, 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 7.4, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg/ml leupeptin, and 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and incubated at 4°C for 30 min. Lysates were centrifuged and the supernatant was used in immunoprecipitation experiments essentially as described above. HA-tagged neurofascin 186 was detected with monoclonal antibody anti-HA.11 (Covance Research Products, Inc.).

Immunocytochemistry

Transfected tsA-201 cells were plated on poly-l-lysine–coated glass coverslips for 24 h and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Coverslips were blocked in 5% avidin, followed by 5% biotin, and then 10% milk solution in TBS. Primary antibody was added at a 1:100 (anti-β1extra) or 1:1,000 dilution (anti-HA.11) in TBS containing 10% milk and 0.025% Triton X-100, and coverslips were incubated overnight at 4°C. Coverslips were then incubated with a 1:300 dilution of biotin-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at 37°C, followed by a 1-h incubation with fluorescein-conjugated avidin (Vector Laboratories). Coverslips were washed, dried, and mounted on glass slides in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories), and visualized under a confocal laser scanning microscope (model MRC 600; Bio-Rad Laboratories).

For staining of intact sciatic nerve, adult rats were anesthetized with nembutal and intracardially perfused with a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde in PB (0.1 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.4). The sciatic nerves were removed, postfixed for 2 h, and sunk in successive solutions of 10 and 30% (wt/vol) sucrose in PB at 4°C over a period of 72 h. Sciatic nerves were embedded in OCT compound, and 20 μm sections were cut and thaw mounted onto Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific). Sciatic sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, rinsed, and then blocked using 5% normal goat serum and 5% nonfat milk in 0.1 M TBS for 1 h. The sections were then incubated in anti-β1extra antibody (diluted 1:15) overnight at room temperature, rinsed in TBS for 30 min, incubated in biotinylated goat anti–rabbit IgG (diluted 1:300; Vector Laboratories), rinsed in TBS for 30 min, and finally incubated in avidin d-fluorescein (diluted 1:300; Vector Laboratories) for 1 h. All antibodies were diluted in TBS containing 5% milk, 5% normal goat serum, and 0.05% Triton X-100. The slides were then rinsed in TBS for 5 min, in TB for 20 min, and in distilled water for 2 min, coverslipped with Vectashield, sealed with nail polish, and viewed using an MRC 600 confocal microscope. Control sections were incubated in normal rabbit serum, or the primary antibody was omitted. In both instances, no specific staining was observed.

For staining of teased sciatic nerves, fresh sciatic nerve removed from 3- and 10-d-old rats was rinsed in PB, treated with collagenase (3.5 mg/ml of PB) for 15 min, rinsed in PB, teased apart on a slide coated with cell tak, rinsed with PB, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, rinsed, and then blocked using 10% normal goat serum in TBS for 1 h. The sections were then incubated in anti-β1extra (diluted 1:15) overnight at room temperature, and processed for immunocytochemistry.

Acknowledgments

We thank Thuy Vien for excellent technical assistance.

This research was supported by the Wellcome Trust (C.F. Ratcliffe) and National Institutes of Health Research Grant NS25704 (W.A. Catterall).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: CAM, cell adhesion molecule; FN, fibronectin; GPI, glycophosphatidylinositol; HA, hemagglutinin; RPTPβ, receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase β.

References

- Auld, V.J., A.L. Goldin, D.S. Krafte, W.A. Catterall, H.A. Lester, N. Davidson, and R.J. Dunn. 1990. A neutral amino acid change in segment IIS4 dramatically alters the gating properties of the voltage-dependent sodium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 87:323–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catterall, W.A. 1992. Cellular and molecular biology of voltage-gated sodium channels. Physiol. Rev. 72:S15–S48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J.Q., S. Lambert, and V. Bennett. 1996. Molecular composition of the node of Ranvier: identification of ankyrin-binding cell adhesion molecules neurofascin (mucin+/third FNIII domain−) and NrCAM at nodal axon segments. J. Cell Biol. 135:1355–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellisman, M.H., and S.R. Levinson. 1982. Immunocytochemical localization of sodium channel distributions in the excitable membranes of Electrophorus electricus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 79:6707–6711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freigang, J., K. Proba, L. Leder, K. Diederichs, P. Sonderegger, and W. Welte. 2000. The crystal structure of the ligand binding module of axonin-1/TAG-1 suggests a zipper mechanism for neural cell adhesion. Cell. 101:425–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garver, T.D., Q. Ren, S. Tuvia, and V. Bennett. 1997. Tyrosine phosphorylation at a site highly conserved in the L1 family of cell adhesion molecules abolishes ankyrin binding and increases lateral mobility of neurofascin. J. Cell Biol. 137:703–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom, L.L., and W.A. Catterall. 1996. Na+ channel subunits and Ig domains. Nature. 383:307–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom, L.L., K.S. De Jongh, D.E. Patton, B.F. Reber, J. Offord, H. Charbonneau, K. Walsh, A.L. Goldin, and W.A. Catterall. 1992. Primary structure and functional expression of the beta 1 subunit of the rat brain sodium channel. Science. 256:839–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom, L.L., D.S. Ragsdale, K.S. De Jongh, R.E. Westenbroek, B.F. Reber, T. Scheuer, and W.A. Catterall. 1995. Structure and function of the beta 2 subunit of brain sodium channels, a transmembrane glycoprotein with a CAM motif. Cell. 83:433–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kordeli, E., S. Lambert, and V. Bennett. 1995. Ankyrin G. A new ankyrin gene with neural-specific isoforms localized at the axonal initial segment and node of Ranvier. J. Biol. Chem. 270:2352–2359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert, S., J.Q. Davis, and V. Bennett. 1997. Morphogenesis of the node of Ranvier: coclusters of ankyrin and ankyrin-binding integral proteins define early developmental intermediates. J. Neurosci. 17:7025–7036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, J.B., P.D. Canoll, O. Silvennoinen, G. Barnea, B. Morse, A.M. Honegger, J.T. Huang, L.A. Cannizzaro, S.H. Park, T. Druck, et al. 1993. The cloning of a receptor-type protein tyrosine phosphatase expressed in the central nervous system. J. Biol. Chem. 268:10573–10581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, J.D., K. Kazen-Gillespie, M. Hortsch, and L.L. Isom. 2000. Sodium channel beta subunits mediate homophilic cell adhesion and recruit ankyrin to points of cell–cell contact. J. Biol. Chem. 275:11383–11388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, K.A., J. Srinivasan, K. White, T. Scheuer, and W.A. Catterall. 1999. The extracellular domain of the beta subunit is both necessary and sufficient for beta 1–like modulation of sodium channel gating. J. Biol. Chem. 274:32638–32646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morales, G., M. Hubert, T. Brummendorf, U. Treubert, A. Tarnok, U. Schwarz, and F.G. Rathjen. 1993. Induction of axonal growth by heterophilic interactions between the cell surface recognition proteins F11 and Nr-CAM/Bravo. Neuron. 11:1113–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, K., E.B. Stevens, B. Shah, P.J. Cox, A.K. Dixon, K. Lee, R.D. Pinnock, J. Hughes, P.J. Richardson, K. Mizuguchi, and A.P. Jackson. 2000. Beta 3: an additional auxiliary subunit of the voltage-sensitive sodium channel that modulates channel gating with distinct kinetics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:2308–2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiwaki, T., N. Maeda, and M. Noda. 1998. Characterization and developmental regulation of proteoglycan-type protein tyrosine phosphatase zeta/RPTPbeta isoforms. J. Biochem. 123:458–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasband, M.N., E. Peles, J.S. Trimmer, S.R. Levinson, S.E. Lux, and P. Shrager. 1999. Dependence of nodal sodium channel clustering on paranodal axoglial contact in the developing CNS. J. Neurosci. 19:7516–7528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe, C.F., Y. Qu, K.A. McCormick, V.C. Tibbs, J.E. Dixon, T. Scheuer, and W.A. Catterall. 2000. A sodium channel signaling complex: modulation by associated receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase beta. Nat. Neurosci. 3:437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai, T., M. Lustig, M. Nativ, J.J. Hemperly, J. Schlessinger, E. Peles, and M. Grumet. 1997. Induction of neurite outgrowth through contactin and Nr-CAM by extracellular regions of glial receptor tyrosine phosphatase beta. J. Cell Biol. 136:907–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzer, J.L. 1997. Clustering sodium channels at the node of Ranvier: close encounters of the axon-glia kind. Neuron. 18:843–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, S.E., J. Li, P.E. Schauwecker, T.H. McNeill, and S.R. Salton. 1996. Comparison of RPTP zeta/beta, phosphacan, and trkB mRNA expression in the developing and adult rat nervous system and induction of RPTP zeta/beta and phosphacan mRNA following brain injury. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 40:79–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, Y., L. Elmer, J. Davis, V. Bennett, and K. Angelides. 1988. Ankyrin and spectrin associate with voltage-dependent sodium channels in brain. Nature. 333:177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan, J., M. Schachner, and W.A. Catterall. 1998. Interaction of voltage-gated sodium channels with the extracellular matrix molecules tenascin-C and tenascin-R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:15753–15757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiotra, P.C., K. Theodorakis, J. Papamatheakis, and D. Karagogeos. 1996. The fibronectin domains of the neural adhesion molecule TAX-1 are necessary and sufficient for homophilic binding. J. Biol. Chem. 271:29216–29222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vabnick, I., S.D. Novakovic, S.R. Levinson, M. Schachner, and P. Shrager. 1996. The clustering of axonal sodium channels during development of the peripheral nervous system. J. Neurosci. 16:4914–4922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmer, H., R. Leuschner, U. Zacharias, and F.G. Rathjen. 1996. Neurofascin induces neurites by heterophilic interactions with axonal NrCAM while NrCAM requires F11 on the axonal surface to extend neurites. J. Cell Biol. 135:1059–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkmer, H., U. Zacharias, U. Norenberg, and F.G. Rathjen. 1998. Dissection of complex molecular interactions of neurofascin with axonin-1, F11, and tenascin-R, which promote attachment and neurite formation of tectal cells. J. Cell Biol. 142:1083–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollner, D.A., R. Scheinman, and W.A. Catterall. 1988. Sodium channel expression and assembly during development of retinal ganglion cells. Neuron. 1:727–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.C., D.S. Ragsdale, J.D. Malhotra, L.N. Mattei, P.E. Braun, M. Schachner, and L.L. Isom. 1999. Tenascin-R is a functional modulator of sodium channel beta subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 274:26511–26517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., J.Q. Davis, S. Carpenter, and V. Bennett. 1998. Structural requirements for association of neurofascin with ankyrin. J. Biol. Chem. 273:30785–30794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D., S. Lambert, P.L. Malen, S. Carpenter, L.M. Boland, and V. Bennett. 1998. Ankyrin G is required for clustering of voltage-gated Na channels at axon initial segments and for normal action potential firing. J. Cell Biol. 143:1295–1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]