ES

Executive Summary

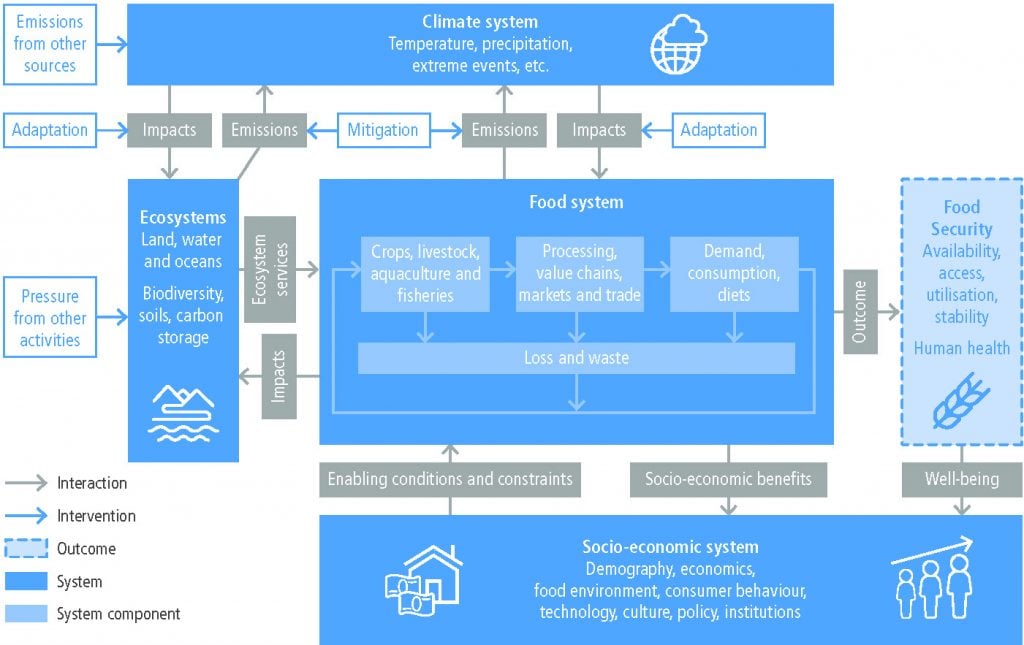

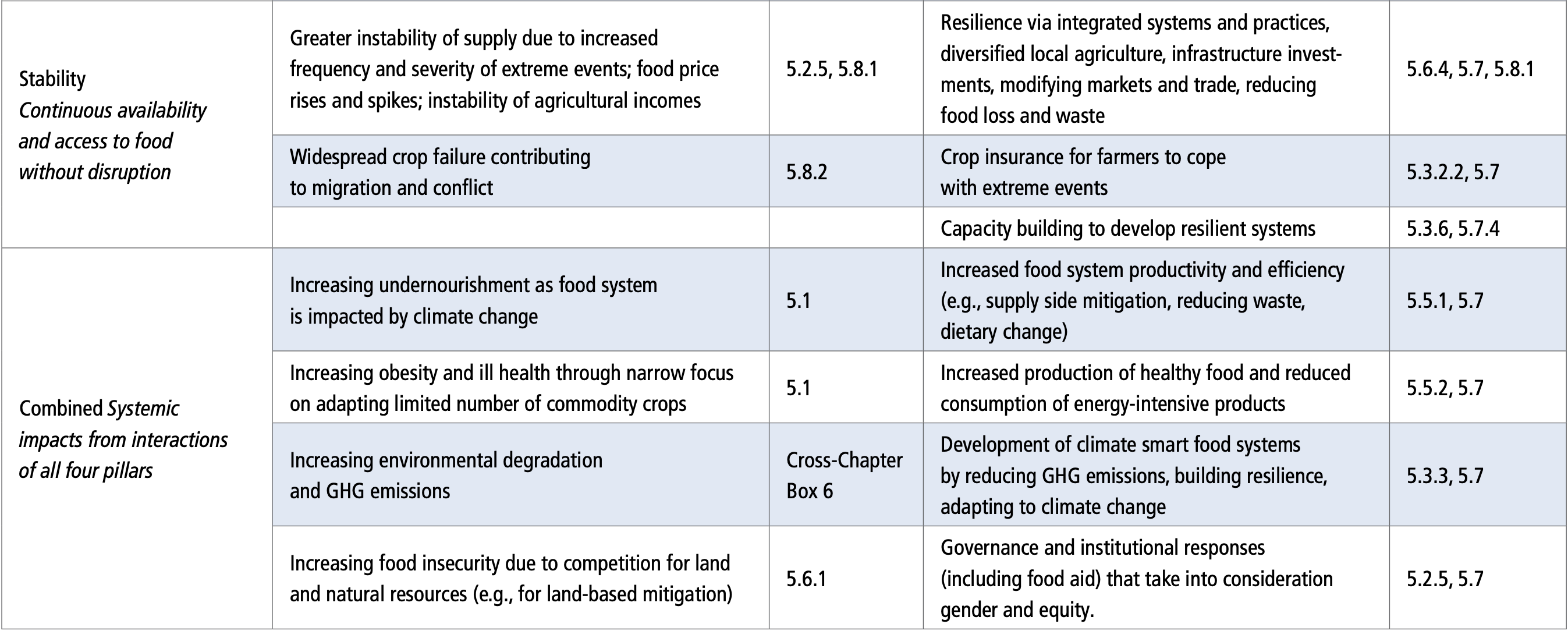

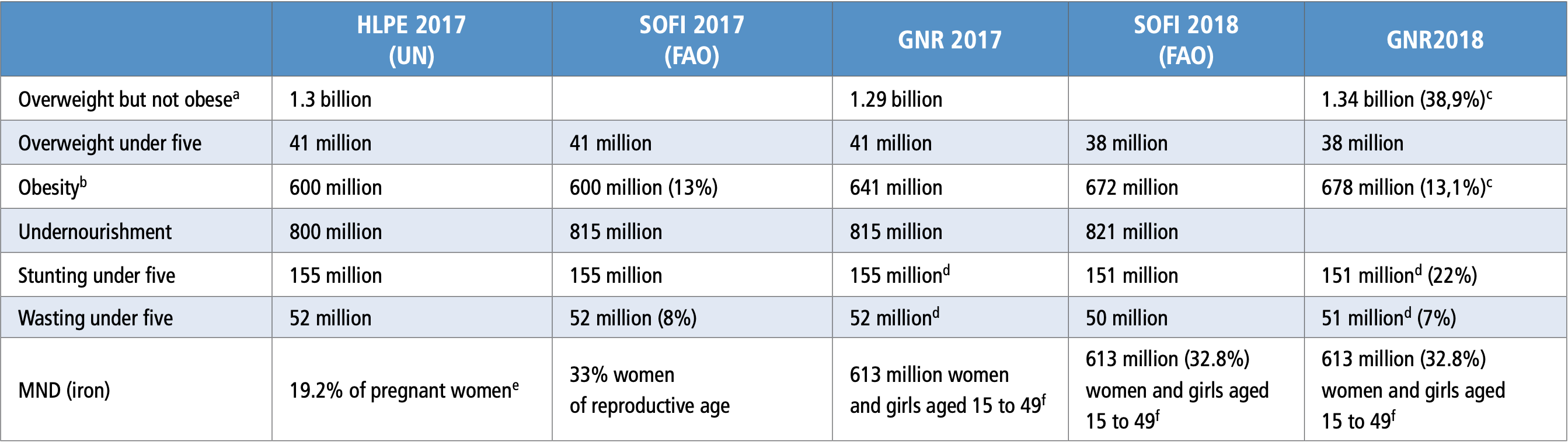

The current food system (production, transport, processing, packaging, storage, retail, consumption, loss and waste) feeds the great majority of world population and supports the livelihoods of over 1 billion people. Since 1961, food supply per capita has increased more than 30%, accompanied by greater use of nitrogen fertilisers (increase of about 800%) and water resources for irrigation (increase of more than 100%). However, an estimated 821 million people are currently undernourished, 151 million children under five are stunted, 613 million women and girls aged 15 to 49 suffer from iron deficiency, and 2 billion adults are overweight or obese. The food system is under pressure from non-climate stressors (e.g., population and income growth, demand for animal-sourced products), and from climate change. These climate and non-climate stresses are impacting the four pillars of food security (availability, access, utilisation, and stability). {5.1.1, 5.1.2}

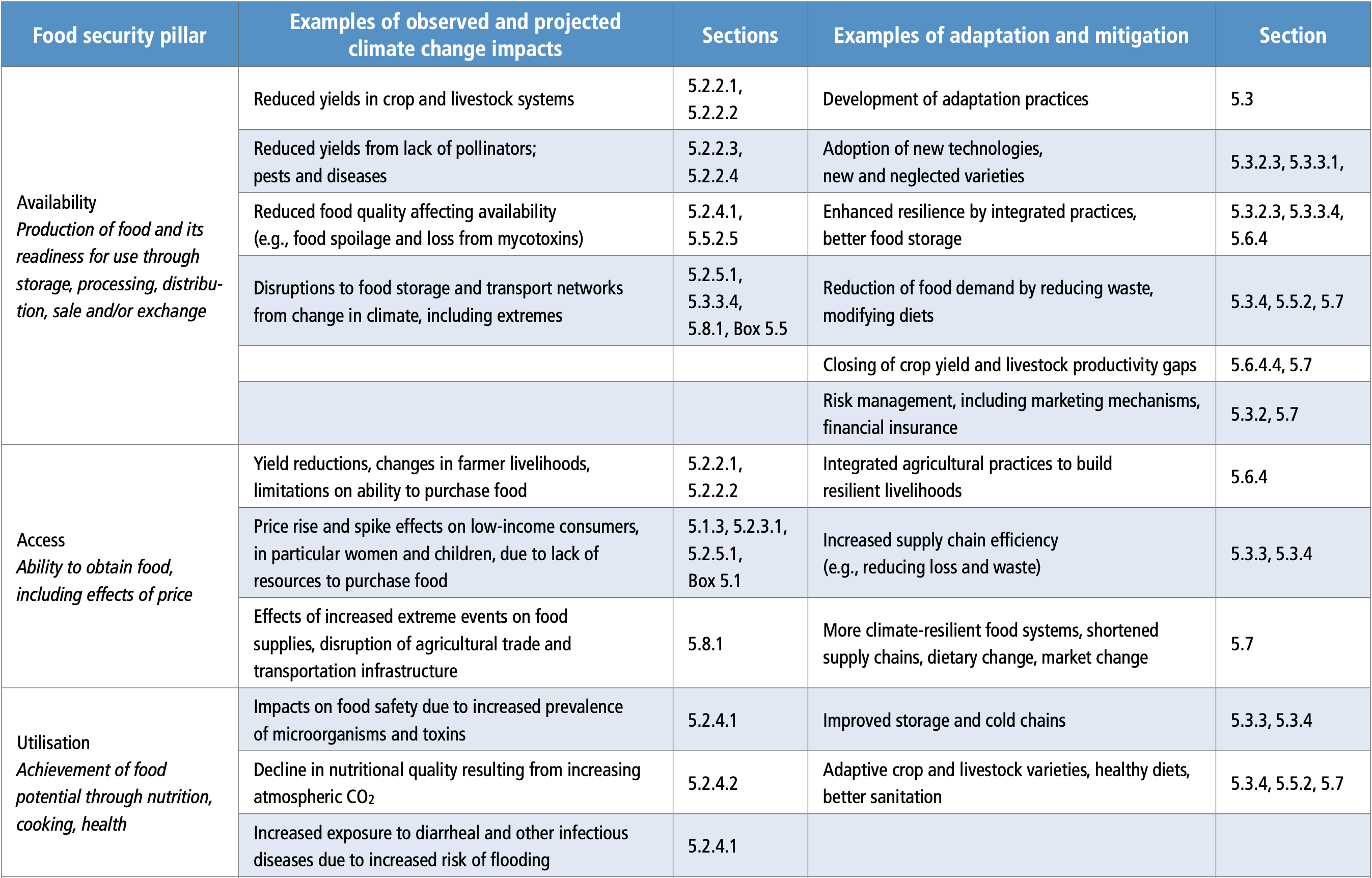

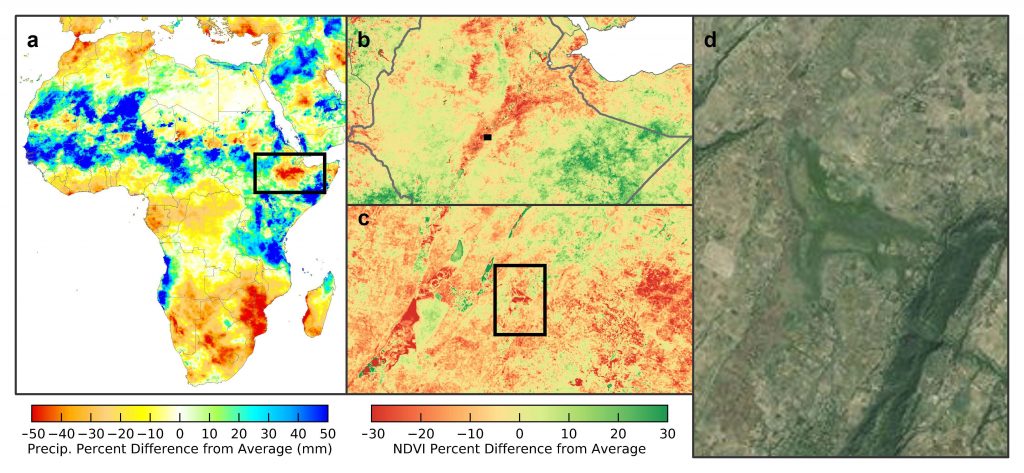

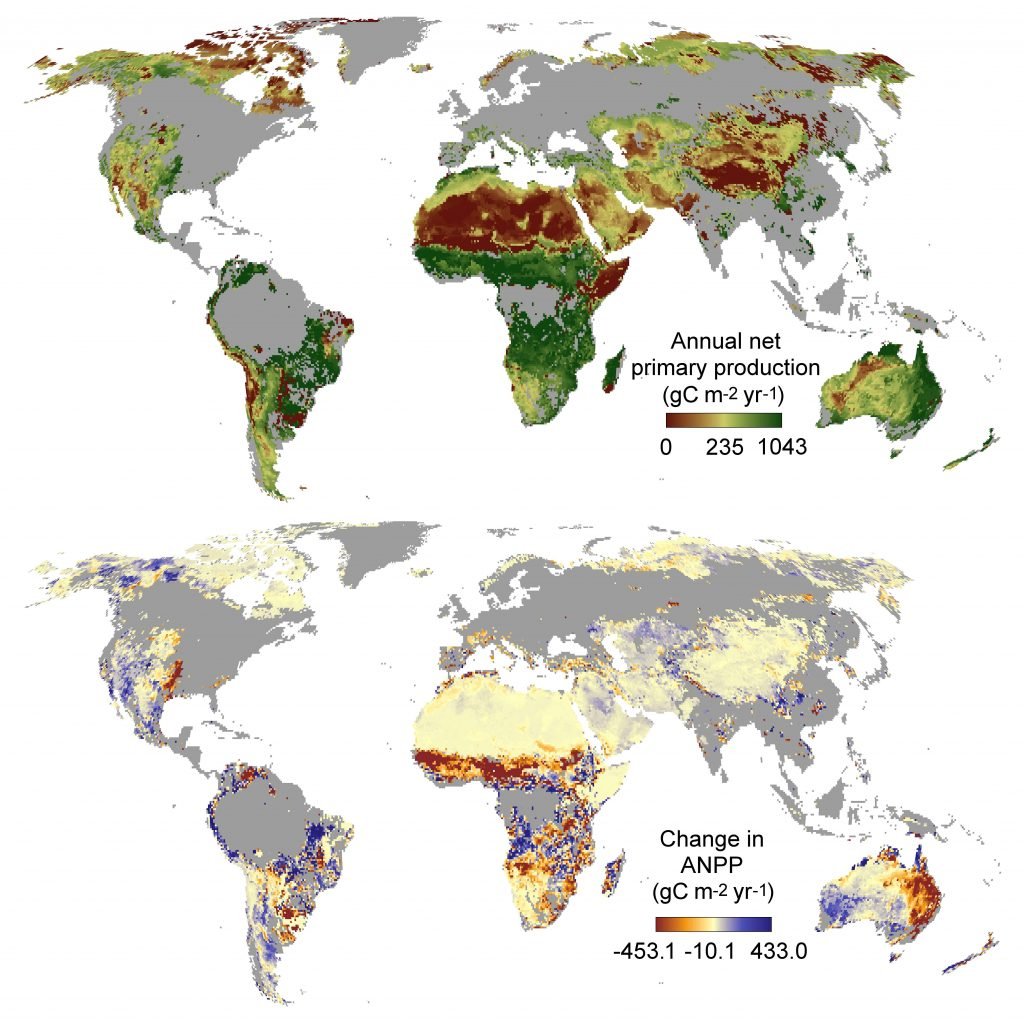

Observed climate change is already affecting food security through increasing temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and greater frequency of some extreme events (high confidence). Studies that separate out climate change from other factors affecting crop yields have shown that yields of some crops (e.g., maize and wheat) in many lower-latitude regions have been affected negatively by observed climate changes, while in many higher-latitude regions, yields of some crops (e.g., maize, wheat, and sugar beets) have been affected positively over recent decades. Warming compounded by drying has caused large negative effects on yields in parts of the Mediterranean. Based on indigenous and local knowledge (ILK), climate change is affecting food security in drylands, particularly those in Africa, and high mountain regions of Asia and South America. {5.2.2}

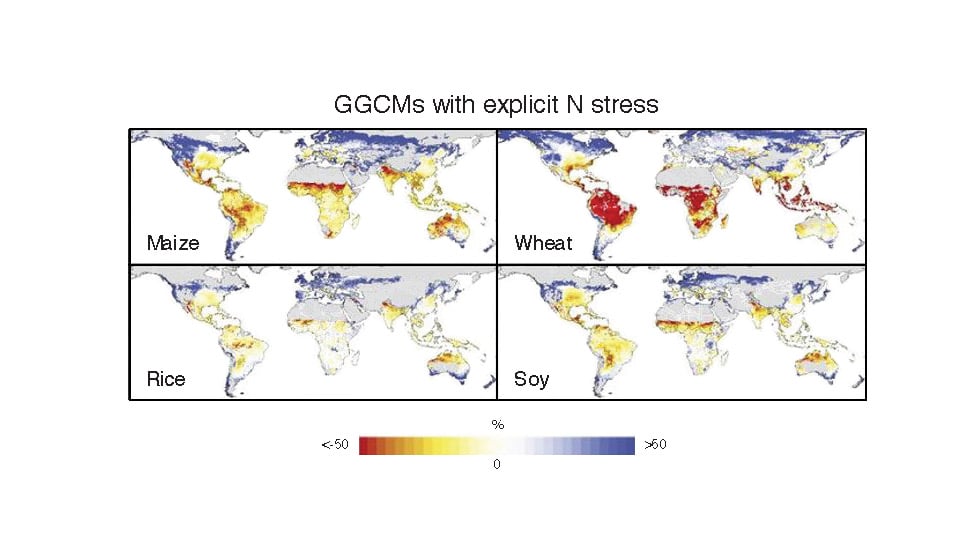

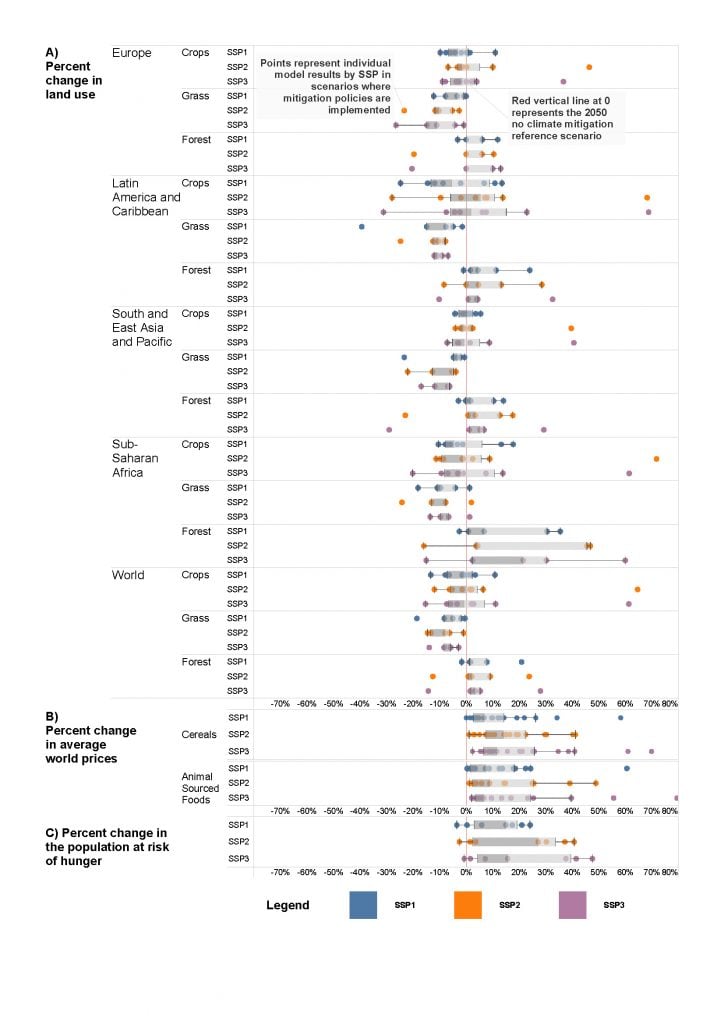

Food security will be increasingly affected by projected future climate change (high confidence). Across Shared Socio-economic Pathways (SSPs) 1, 2, and 3, global crop and economic models projected a 1–29% cereal price increase in 2050 due to climate change (RCP 6.0), which would impact consumers globally through higher food prices; regional effects will vary (high confidence). Low-income consumers are particularly at risk, with models projecting increases of 1–183 million additional people at risk of hunger across the SSPs compared to a no climate change scenario (high confidence). While increased CO2 is projected to be beneficial for crop productivity at lower temperature increases, it is projected to lower nutritional quality (high confidence) (e.g., wheat grown at 546–586 ppm CO2 has 5.9–12.7% less protein, 3.7–6.5% less zinc, and 5.2–7.5% less iron). Distributions of pests and diseases will change, affecting production negatively in many regions (high confidence). Given increasing extreme events and interconnectedness, risks of food system disruptions are growing (high confidence). {5.2.3, 5.2.4}

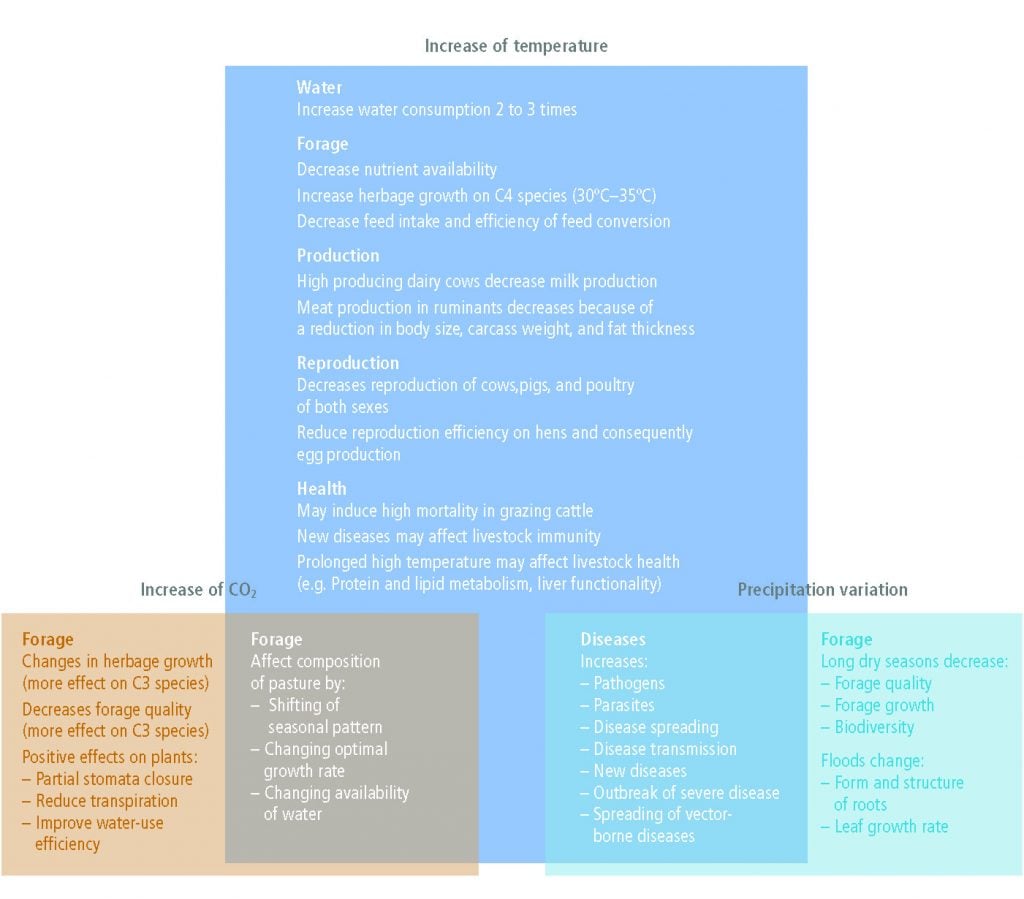

Vulnerability of pastoral systems to climate change is very high (high confidence). Pastoralism is practiced in more than 75% of countries by between 200 and 500 million people, including nomadic communities, transhumant herders, and agropastoralists. Impacts in pastoral systems in Africa include lower pasture and animal productivity, damaged reproductive function, and biodiversity loss. Pastoral system vulnerability is exacerbated by non-climate factors (land tenure, sedentarisation, changes in traditional institutions, invasive species, lack of markets, and conflicts). {5.2.2}

Fruit and vegetable production, a key component of healthy diets, is also vulnerable to climate change (medium evidence, high agreement). Declines in yields and crop suitability are projected under higher temperatures, especially in tropical and semi-tropical regions. Heat stress reduces fruit set and speeds up development of annual vegetables, resulting in yield losses, impaired product quality, and increasing food loss and waste. Longer growing seasons enable a greater number of plantings to be cultivated and can contribute to greater annual yields. However, some fruits and vegetables need a period of cold accumulation to produce a viable harvest, and warmer winters may constitute a risk. {5.2.2}

Food security and climate change have strong gender and equity dimensions (high confidence). Worldwide, women play a key role in food security, although regional differences exist. Climate change impacts vary among diverse social groups depending on age, ethnicity, gender, wealth, and class. Climate extremes have immediate and long-term impacts on livelihoods of poor and vulnerable communities, contributing to greater risks of food insecurity that can be a stress multiplier for internal and external migration (medium confidence). {5.2.6} Empowering women and rights-based approaches to decision-making can create synergies among household food security, adaptation, and mitigation. {5.6.4}

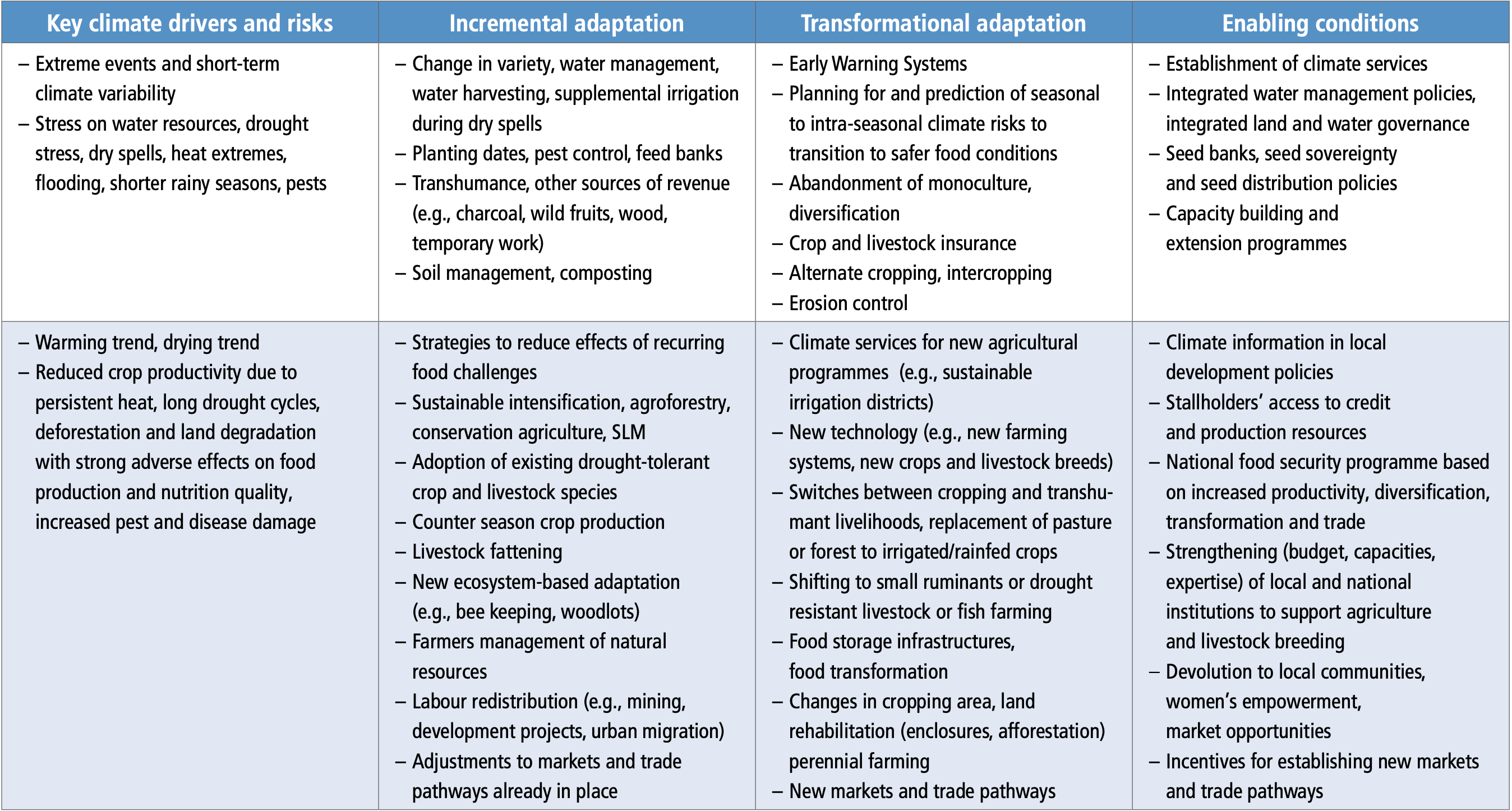

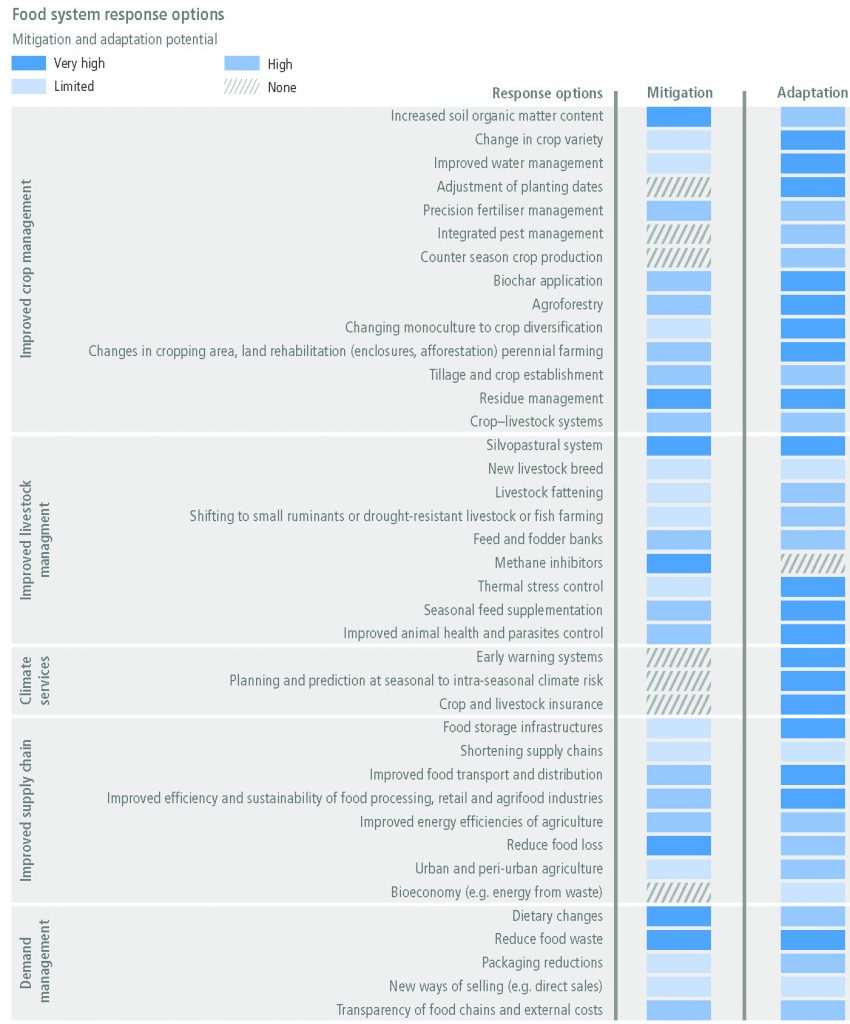

Many practices can be optimised and scaled up to advance adaptation throughout the food system (high confidence). Supply-side options include increased soil organic matter and erosion control, improved cropland, livestock, grazing land management, and genetic improvements for tolerance to heat and drought. Diversification in the food system (e.g., implementation of integrated production systems, broad-based genetic resources, and heterogeneous diets) is a key strategy to reduce risks (medium confidence). Demand-side adaptation, such as adoption of healthy and sustainable diets, in conjunction with reduction in food loss and waste, can contribute to adaptation through reduction in additional land area needed for food production and associated food system vulnerabilities. ILK can contribute to enhancing food system resilience (high confidence). {5.3, 5.6.3 Cross-Chapter Box 6 in Chapter 5}

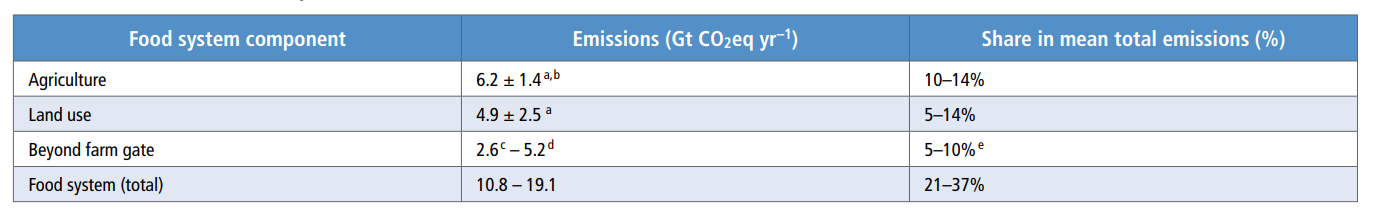

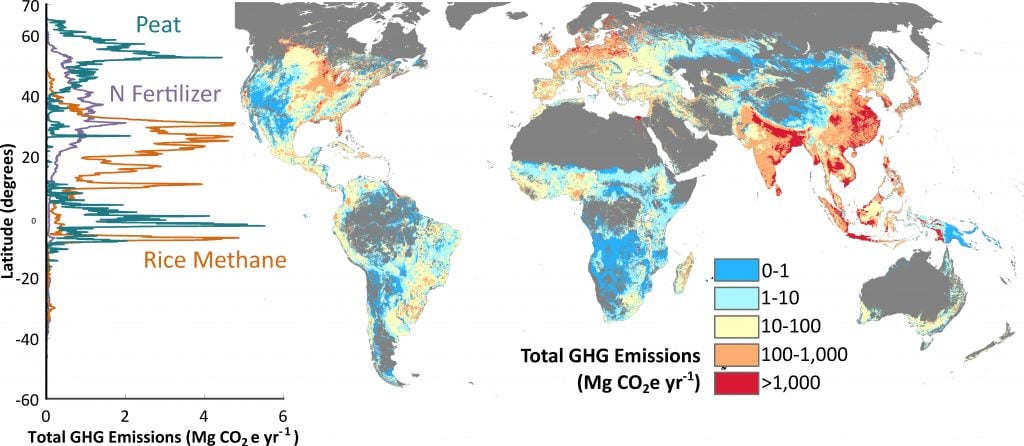

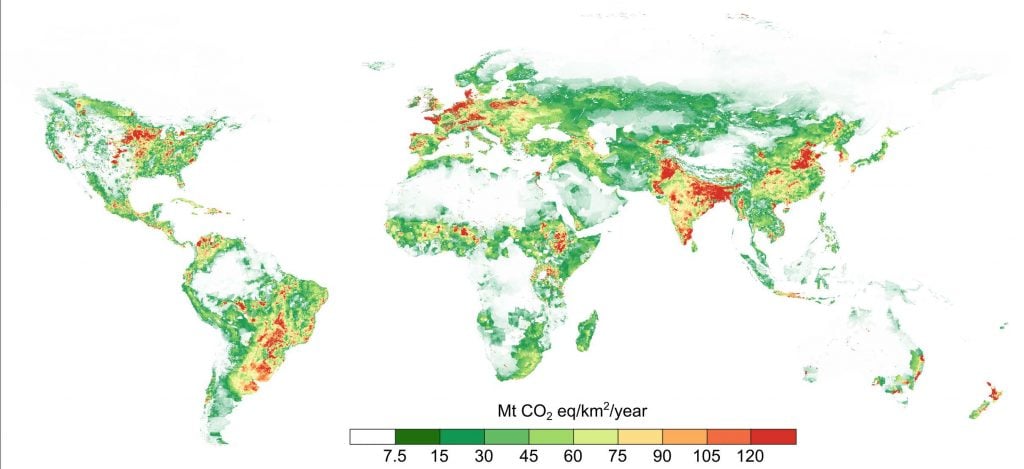

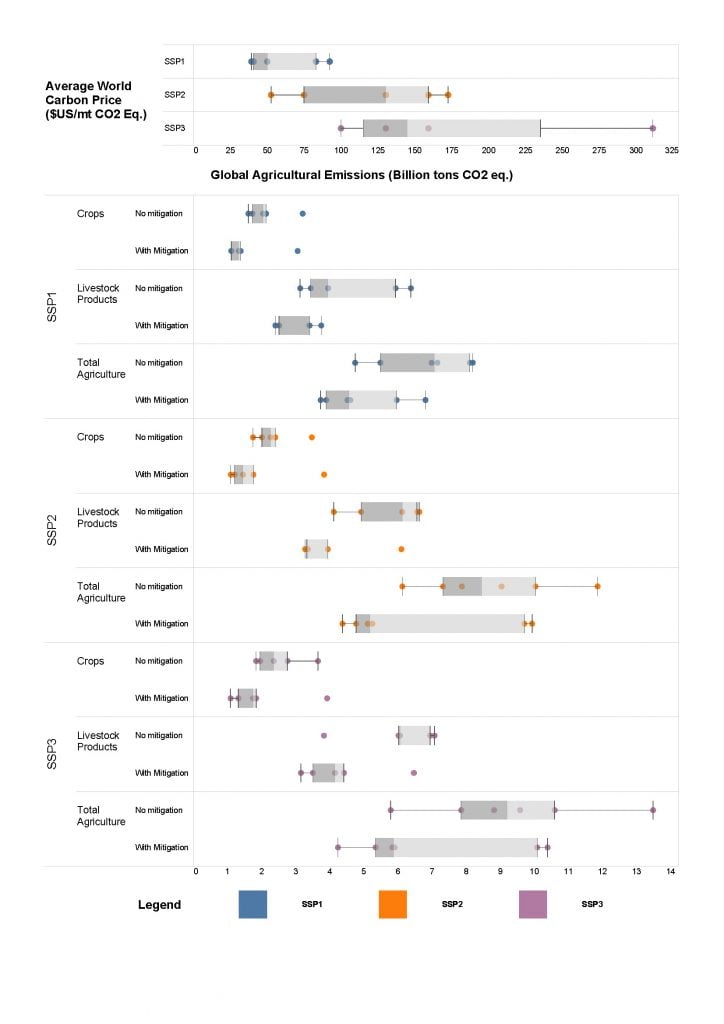

About 21–37% of total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are attributable to the food system. These are from agriculture and land use, storage, transport, packaging, processing, retail, and consumption (medium confidence). This estimate includes emissions of 9–14% from crop and livestock activities within the farm gate and 5–14% from land use and land-use change including deforestation and peatland degradation (high confidence); 5–10% is from supply chain activities (medium confidence). This estimate includes GHG emissions from food loss and waste. Within the food system, during the period 2007–2016, the major sources of emissions from the supply side were agricultural production, with crop and livestock activities within the farm gate generating respectively 142 ± 42 TgCH4 yr–1 (high confidence) and 8.0 ± 2.5 TgN2O yr–1 (high confidence), and CO2 emissions linked to relevant land-use change dynamics such as deforestation and peatland degradation, generating 4.9 ± 2.5 GtCO2 yr-1. Using 100-year GWP values (no climate feedback) from the IPCC AR5, this implies that total GHG emissions from agriculture were 6.2 ± 1.4 GtCO2-eq yr-1, increasing to 11.1 ± 2.9 GtCO2-eq yr–1 including relevant land use. Without intervention, these are likely to increase by about 30–40% by 2050, due to increasing demand based on population and income growth and dietary change (high confidence). {5.4}

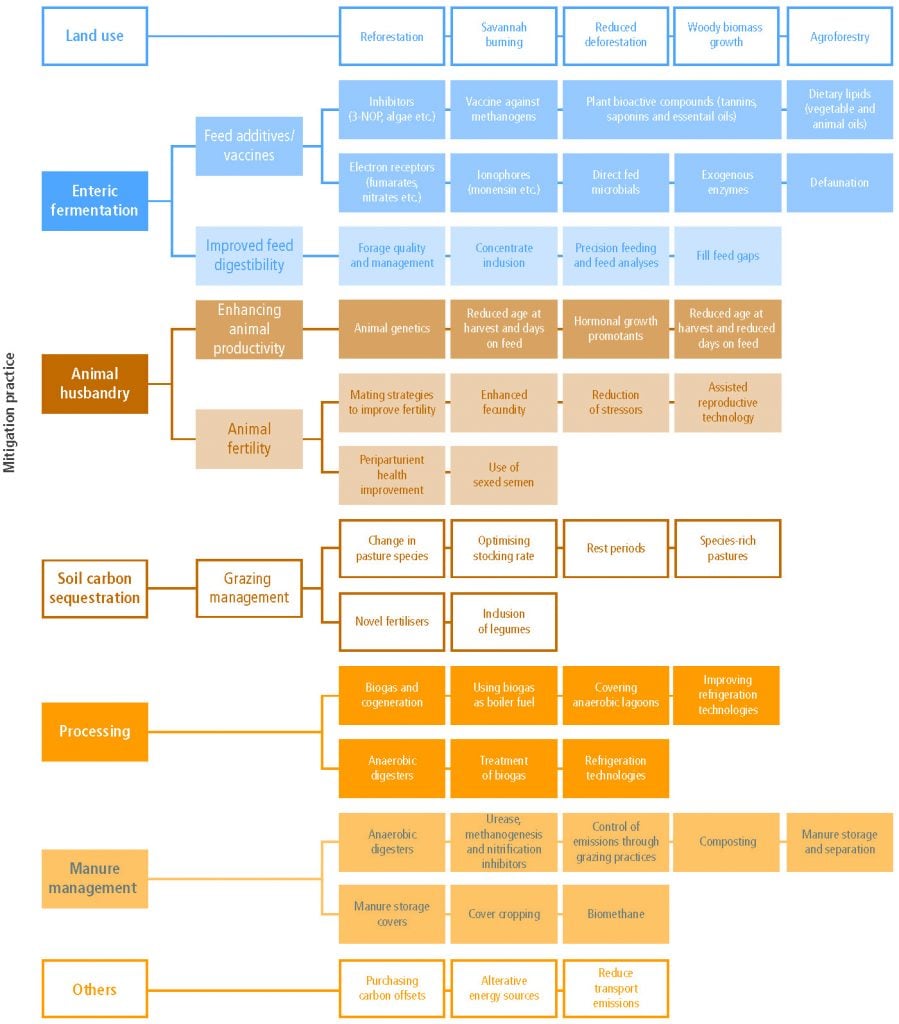

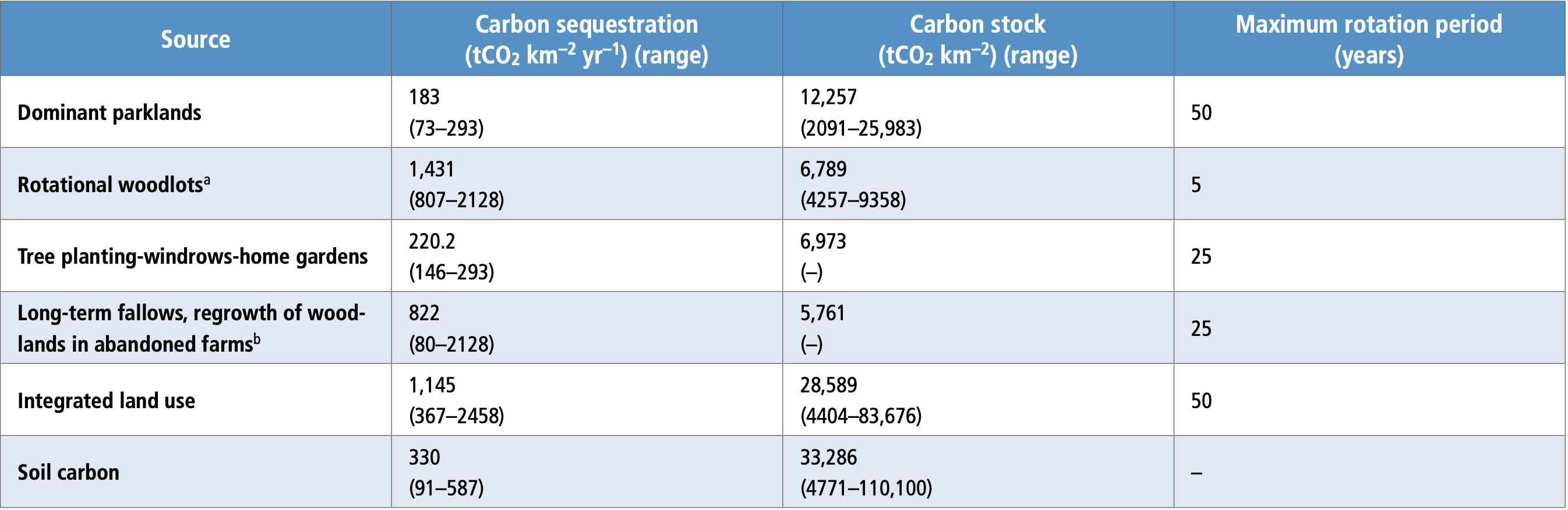

Supply-side practices can contribute to climate change mitigation by reducing crop and livestock emissions, sequestering carbon in soils and biomass, and by decreasing emissions intensity within sustainable production systems (high confidence). Total technical mitigation potential from crop and livestock activities and agroforestry is estimated as 2.3–9.6 GtCO2-eq yr–1 by 2050 (medium confidence). Options with large potential for GHG mitigation in cropping systems include soil carbon sequestration (at decreasing rates over time), reductions in N2O emissions from fertilisers, reductions in CH4 emissions from paddy rice, and bridging of yield gaps. Options with large potential for mitigation in livestock systems include better grazing land management, with increased net primary production and soil carbon stocks, improved manure management, and higher-quality feed. Reductions in GHG emissions intensity (emissions per unit product) from livestock can support reductions in absolute emissions, provided appropriate governance to limit total production is implemented at the same time (medium confidence). {5.5.1}

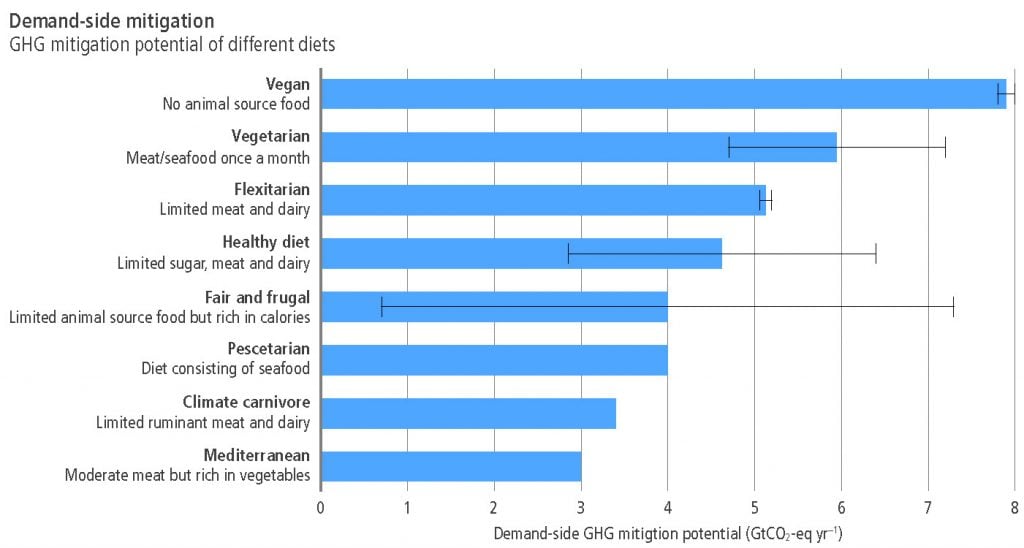

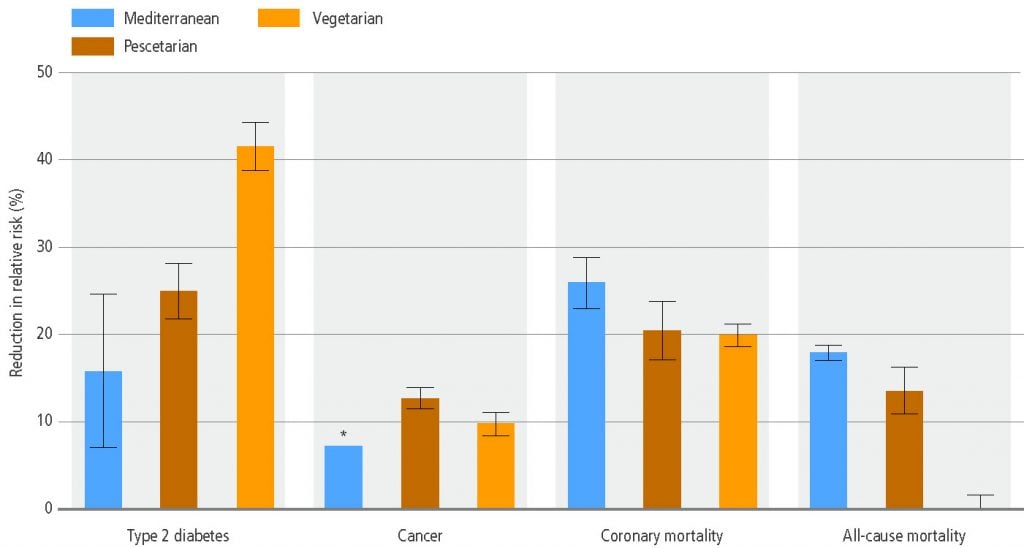

Consumption of healthy and sustainable diets presents major opportunities for reducing GHG emissions from food systems and improving health outcomes (high confidence). Examples of healthy and sustainable diets are high in coarse grains, pulses, fruits and vegetables, and nuts and seeds; low in energy-intensive animal-sourced and discretionary foods (such as sugary beverages); and with a carbohydrate threshold. Total technical mitigation potential of dietary changes is estimated as 0.7–8.0 GtCO2-eq yr–1 by 2050 (medium confidence). This estimate includes reductions in emissions from livestock and soil carbon sequestration on spared land, but co-benefits with health are not taken into account. Mitigation potential of dietary change may be higher, but achievement of this potential at broad scales depends on consumer choices and dietary preferences that are guided by social, cultural, environmental, and traditional factors, as well as income growth. Meat analogues such as imitation meat (from plant products), cultured meat, and insects may help in the transition to more healthy and sustainable diets, although their carbon footprints and acceptability are uncertain. {5.5.2, 5.6.5}

Reduction of food loss and waste could lower GHG emissions and improve food security (medium confidence). Combined food loss and waste amount to 25–30% of total food produced (medium confidence). During 2010–2016, global food loss and waste equalled 8–10% of total anthropogenic GHG emissions (medium confidence); and cost about 1 trillion USD2012 per year (low confidence). Technical options for reduction of food loss and waste include improved harvesting techniques, on-farm storage, infrastructure, and packaging. Causes of food loss (e.g., lack of refrigeration) and waste (e.g., behaviour) differ substantially in developed and developing countries, as well as across regions (robust evidence, medium agreement). {5.5.2}

Agriculture and the food system are key to global climate change responses. Combining supply-side actions such as efficient production, transport, and processing with demand-side interventions such as modification of food choices, and reduction of food loss and waste, reduces GHG emissions and enhances food system resilience (high confidence). Such combined measures can enable the implementation of large-scale land-based adaptation and mitigation strategies without threatening food security from increased competition for land for food production and higher food prices. Without combined food system measures in farm management, supply chains, and demand, adverse effects would include increased numbers of malnourished people and impacts on smallholder farmers (medium evidence, high agreement). Just transitions are needed to address these effects. {5.5, 5.6, 5.7}

For adaptation and mitigation throughout the food system, enabling conditions need to be created through policies, markets, institutions, and governance (high confidence). For adaptation, resilience to increasing extreme events can be accomplished through risk sharing and transfer mechanisms such as insurance markets and index-based weather insurance (high confidence).Publichealthpoliciestoimprovenutrition–suchasschool procurement, health insurance incentives, and awareness-raising campaigns – can potentially change demand, reduce healthcare costs, and contribute to lower GHG emissions (limited evidence, high agreement). Without inclusion of comprehensive food system responses in broader climate change policies, the mitigation and adaptation potentials assessed in this chapter will not be realised and food security will be jeopardised (high confidence). {5.7, 5.8}