A Tribute to one of India’s Holiest And Most Ancient Waterways

Excerpts from a photographic odyssey by hari mahidhar, with a flowing tribute to narmada by vithal c. nadkarni

Over 2,000 years ago, the cartographer who composed the magisterial atlas called Periplus Maris Erythraei knew this river as Nammadus. Two centuries later, Ptolemy referred to the Narmada as Namade. The Narmada was around when Asia and Australia were fused into a single landmass. At that time there were no Himalayas. Nor was the Ganga even a flicker in the eyes of the Creator. That was also when great hordes of dinosaurs used to flock to the sandy banks of the Narmada to lay their eggs in communal nests. Then catastrophe hit the Jurassic world: the Indian tectonic plate collided with the Tibetan Plateau and Australia broke off from Asia, like a biscuit, to float off into the southern seas, as did Madagascar and Africa. Through all these cataclysms, the Narmada continued to flow serenely. She grew even longer and stronger. To the millions who believe in her transformative magic, the Narmada is the holiest of holy rivers. Legend links her birth to the sweat that emerged from Shiva, the Supreme God. That makes the Narmada so holy that merely looking at her, let alone by actually bathing in her, devotees are said to be cleansed of all their sins! Such is the purifying power of Mother Narmada that even Ma Ganga supposedly incarnates herself as a black cow to visit her elder sister Narmada. The Ganga does this once a year just to wash off the “sins” piled up in her waters by her devotees! The Narmada needs no such cleansing. This may explain why the “Sinless River” (Narmada literally means “Harbinger of Joy”) is worshiped throughout her 1,312-km length—from the point of her origin to her merger into the ocean. This pilgrimage along the river is called Narmada Parikrama, which is a cultural and spiritual spectacle of enduring sociological significance. Benevolent rivers like the Narmada hold shifting mirrors to our world. They give us back a fluid landscape that allows the spectator to sample the dazzling variety of cultures found in India. The Narmada basin is a region of great scenic spectacles and mind-blowing biological diversity. The seeker can marvel at everything here—from proto-human rock art galleries and Neolithic settlements to imposing fortresses and temples, Jain icons, churches, mosques and gurudwaras, not to forget wild forests and their colorful denizens.

All this and more has been captured through the all-seeing eye of Hari Mahidhar’s digital camera and the brilliant prose of Vithal C. Nadkarni in Benevolent Narmada, from which we offer choice excerpts on the following pages.

Raw beauty: After passing through the smoky cascades at Dhuandhar, the Narmada flows westwards past jagged marble cliffs toward Panchavati.

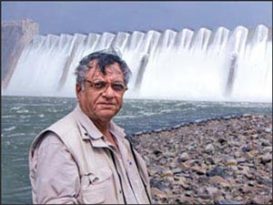

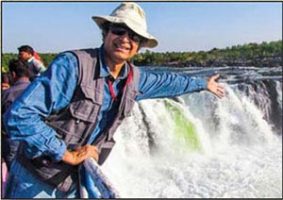

My own tryst with the narmada occurred at Bhedaghat at high noon. It was at a place 19km from Jabalpur, where the river falls over marble rocks in a spectacular waterfall called Dhuandhar. The roar of these smoky cascades is heard long before one actually sees them. That explains why the Narmada is also called Rewa, or the River that Roars. The Narmada reverberated with the noise of millions of water birds in earlier times. Adi Shankaracharya evokes that ecological glory in his Sanskrit hymn Narmada Ashtakam. The reformist-philosopher, who lived in the 8th century ce, describes the river’s “resolute shores” as “resounding with the cacophony of lakhs of birds (Nira-tira-dhira-pakshi-laksha-kujitam).” The master composed the hymn on the banks of the Narmada at Omkareshwar, the Om-shaped island renowned for its Linga of Light shrine. Today there are hardly any birds, but plenty of people milling around on the concrete promenade facing the roaring waters.

As I lean over the wet railing to pose for a selfie, I have an epiphany: even at its zenith, the sun here feels as cool as the moon! Is this the glareless sun that the 13th-century mystic Jnandeva evokes in his Marathi masterpiece, Pasayadan? (The legendary playback singer Lata Mangeshkar has sung this for modern times.) My euphoria vanishes when I look around. A plastic bottle with a blue label, a symbol of our “use-and-throw” culture, winks from the rocks below. In that vaporous environment there are other signs of life, too: through the misty shroud I can make out the silhouette of a pond heron standing still on a ledge. It is waiting for unwary fish and flies, like a wet Ninja, with infinite patience. More startling is the sight of people horsing around on the rocks behind the waterfalls. They seem blissfully oblivious of the consequences of their actions as they go around stomping all over Ma Narmada with their feet. “Blame the river herself for all this,” said Bhartrihari in his Niti-Shatataka. “She shouldn’t have come out of heaven in the first place!” The moral of Bhartrihari’s verse for the 21st century is: descent into “self-pollution” has a thousand faces. To imagine the plight of the Narmada today, we would have to multiply that thousand by a billion! To imagine the impact on the lives of the millions who directly depend on the Narmada, one would have to look at the darker side of “devotion” and “development.” This, however, was not the focus of Hari Mahidhar’s six-year odyssey. His is a celebration rather than a requiem for the river.

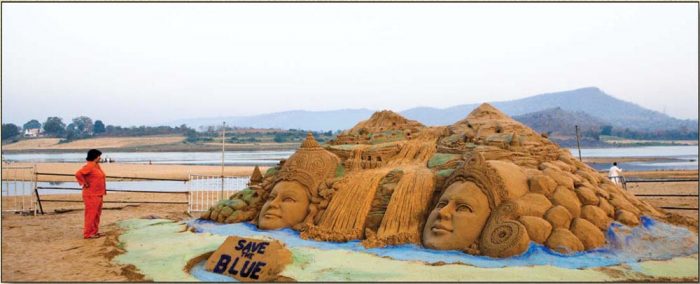

Sand and sandstone: Renowned sand artist Sudarshan Pattnaik (in orange) sculpted these twin faces of the rivers Narmada and Tawa during a river festival held at their confluence, known as the Bandrabhan Sangam;

A Journey for the Soul

Narmada’s sacred landscape seems inseparable from her physical presence. Rising as a small stream in the central highlands of the Indian peninsula, she flows from east to west in the company of her two brothers, the Vindhya and Satpuda Hills. Three km from the source, she drops 30 metres at Kapildhara waterfall and loops further through Mahadeo Hills to take a second fall at Dhuandhar near Jabalpur. Then heading west through the wide Narmada Valley, she falls 274 metres in 483 km through two more waterfalls and numerous rapids before reaching her 27-km-wide estuary near Bharuch.

As we saw earlier, the Narmada is the only river in the world that is circumambulated in her entire length of 1,312 km. This great circumambulation is the Narmada Parikrama. Call it a journey of the soul, for the soul, by the sole; it entails walking along the river from her origin to the finish in the sea and crossing over to the other side and walking right back to the beginning.

It is, however, not just a matter of plodding along the Narmada on one’s feet. “Everybody does that kind of pilgrimage (Tirath ko sab kare),’’ the poet Manrang says. “But if your passions live, how can you cross the ocean of existence?” Mental purity or the right attitude is therefore of the essence. Nor should all this put off the potential Parikramavasi (pilgrim). Ma Narmada’s compassion for her children is said to be so vast that she will supposedly save you even if you don’t actually see her, and merely think of her (Smaranajanmajam papam hanti)!

Nor does the Narmada’s power stop there. So, if thinking of her zaps sins gathered over a lifetime, looking at her sacred waters is said to be three times as potent, and bathing in them a thousand times more effective. The faith of Narmada’s pilgrims is therefore astounding indeed. They are on the road for 3 years, 3 months and 13 days, carrying their meagre belongings on the back; subsisting on alms and the kindness of strangers.

Ever so gracefully, the waters of the Narmada fall from a rocky precipice into an idyllic pond;

Some start their pilgrimage from Bharuch to Amarkantak and back along the opposite bank. Some go from the source to the sea along the southern bank with a return journey along the northern bank. For Bharati Thakur, the entire journey of 2,624km began with a single step. The social worker calls it an “inner journey” in her travelog. “I had to leave the comfort zone of my social network of limited boundaries (simit parivar). In return I got connected to a boundless world (aseem parivar), a veritable Family of Man.”

Bagh Caves lie barely 150 km from the world-heritage site of Ajanta. Like Ajanta, the frescoes at Bagh depict religious as well as secular Buddhist themes. A copper-plate inscription of King Subandhu records a donation made for the repair of the sandstone caves in the 5th century ce.

The Narmada has inspired many such river pilgrimages, each with its own set of rules and rites, all of which continually add to benevolent Ma Narmada’s reputation as a bestower of limitless boons upon those who depend on her bounties.

Mind-Born Maiden

The narmada is intimately bound to shiva, the primordial Great God (Mahadeva) also worshiped as Great Time (Mahakala), and as the first guru (Adinatha), who raised humanity from its animal roots with the gift of yoga. Geologically, too, the Narmada is arguably the oldest river on Earth. “Compared to the Narmada, the Ganges is but a child (Ganga toh bachchi hai),” says Vinayak Peshwa. The geologist is an eighth-generation descendant of Baji Rao Peshwa I, who served as prime minister of the fourth Maratha ruler, Chhatrapati Shahu, in the mid-18th century. Dr Peshwa did his fieldwork on the Narmada and Sone river basins from Jabalpur.

Anthropologically, the banks of the Narmada yield the earliest known traces of South Asian hominids. The Narmada is therefore the very cradle of civilization and the nursery of a mind-boggling variety of cults and cultures. But mythic origins of the river occur in a space beyond mundane time. Here magic reigns supreme. Trapped in a terrible famine, people, rishis and the gods beseech Supreme Shiva: a drop falls from the moon diadem of the Lord with Three Eyes, and from this immortal elixir springs a miraculous being—a girl-child, blue-hued as the lotus, with an electrifying effulgence that eclipses the luminescence of the gods.

Narmada, the Goddess, 11th century. This stone icon, carved for royal Kalachuri patrons in the 11th century and recovered from Tewar village near Bhedaghat, is now located in a modern temple at Kamaniya Gate, Jabalpur.

That moment is recorded in the inscription of the Kalachuri King Yashodharman Vishnuvardhan which calls Narmada “the Moon-born,” or Somodbhava.

Other traditions across the world also reflect this intimate symbolic relationship between water and women: deities like Artemis or Aphrodite of the Greeks, for instance, arise from the waters, as do the river goddesses of India.

Pilgrims worship at the Mai-ki-bagia temple complex, the traditional starting point of the great circumambulation of the Narmada River.

The River of Unity

Another legend links the birth of the narmada to the twin teardrops that fell from the eyes of Brahma, the Creator of the Universe. One cosmic tear led to the formation of the river Sone, and the other yielded Narmada. In yet another mythic version, the Narmada was born out of the sweating form of Shiva lost in meditation on one of the seven peaks of Mount Rikshavant (present day Amarkantak in the Satpudas, which lies at the transection of the Vindhyas and the Maikal Ranges). The Narmada is therefore referred to as Shankari.

The Narmada-Shankari’s holiness is believed to be so pervasive that every rock and pebble in her stream is said to turn into a divine Banalinga. The belief gives rise to the Hindi saying, “Narmada ka har kankar Shankar (Every rock in the Narmada becomes Shiva).” “If this is Ma Narmada’s impact on inanimate stone, just imagine what miracles she must be showering upon us living, breathing human beings,” Pandit Nilu Maharaj, the chief priest of the main Narmada shrine at Amarkantak, says.

This could also explain why the revolutionary theologian Adi Shankaracharya put so much emphasis on daily worship of the river and her stones. “By doing so, the far-sighted acharya turned these seemingly humble stones into icons of great geographical and religious unity for India at an extremely turbulent moment of her history,” explains Parivrajak Swami Gyanananda Saraswati, founder-president of the Shankaracharya Vedic Research Centre in Varanasi.

The formal (saguna) worship of the Narmada also needs to be backed by enlightened conduct as well, cautions Lakshmidhara, the 12th-century author of Krityakalpataru. For if a tirtha alone were enough to sanctify, wouldn’t all the fishes, frogs and crocs living in holy rivers such as the Ganga and the Narmada be instantly purified? The Puranas therefore advise aspirants to “always bathe in the earthly tirthas as well as in the tirthas of the mind and heart.” Only then can they hope to reach the supreme goal of merging with the Universal One, as the Ma Narmada does by embracing the sea.

Rousing River

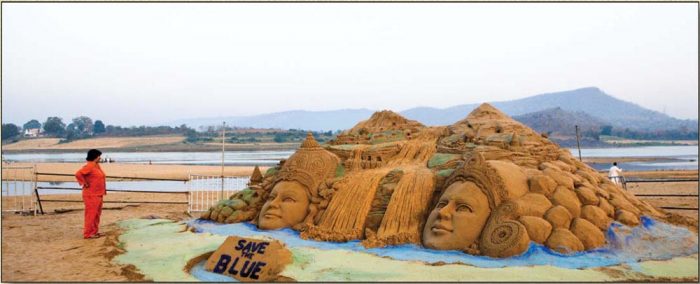

The birthday festival (jayanti) of the narmada, which started on a modest scale in the late 1970s at Narmadapur, Hoshangabad, has grown into a Mega-Fest today. Donation of Lamps (Deepdaan) and Narmada Abhishek (anointing of the River Narmada) with milk and flowers are two of the spectacles that illuminate the night-long festivities. Eight km east of Hoshangabad is the confluence of the burgundy-colored waters of the Tava River with the blue-hued Narmada. The exquisite Narmada temple at Bandarabhan at the confluence is noted for its rousing Narmada Jayanti festivities. Devotees offer milk and flowers to the river at Gwarighat as auspicious red-hued saris and stoles are strung across the banks to mark the emergence of this holiest of holy rivers upon the Earth.

Energy—spiritual and electrical: Devotees gamboling in the sacred waters at the Abhay Ghat, which is designed for safety with a water-breaker wall.

Waters of Creation

The barman ghat of the narmada supposedly takes its name from Brahma the Creator, or Prajapati. He is only the first in a long line of glorious preceptors—such as Manu, Parashara, Vyasa, Atri, Yajnyavalkya, Angira, Bhrigu, Markandeya, Vashistha, Vishwamitra, Bharadwaja, Kapila and Agasthya—who lived and meditated in these hallowed environs. According to another folk belief which we heard during our travels, Barman may be related to the ritual of granting of boons (Bar Mang) that is supposed to happen after the sighting of a holy cistern called Brahma Kund.

The myth of the Progenitor praying at Barman Ghat also resonates with the story of the grandfather of gods, who sports on the waters of creation. Closer to our times, the story of how the deep waves of water spontaneously created the first specks of animated life has been sung in a poem called “The Temple of Nature” by Erasmus Darwin, the grandsire of the father of the Theory of Evolution, Charles Darwin.

In popular imagination, the Narmada is also worshiped as Muktidayani, the Liberating Mother. She is supposed to provide her devotees an escape from the mortal coil and an end to the ceaseless cycle of birth and death. As a destroyer of sin, the river is said to be as invincible as the weapon of Indra called Vajra in the Padma Purana. In the myth of the liberation of waters, as narrated in the Purana, Indra repairs to the banks of the Narmada to cure himself, with penance and purification rites, of the sin of killing the Brahmin enemy of the gods, Vritra.

Sport and spirit: A local fisherman dives courageously into the emerald river waters at Barman Ghat

Melting into Brahman!

Hidden in the names of the world’s rivers is nadi, the indian word for river, This may sound strange, but it’s true, suggests the German paleolinguist Richard Fester. As examples he cites the names of the German river Nidda and the Nida from central Poland, as also the Norwegian nid and English nidd from North Yorkshire. Nada/nadi vibrates thus through rivers big and small.

Yet, Narmada stands apart from them all, possibly because she is the most primordial stream of all. She has been flowing on serenely through earthquakes and landshifts that altered the planet forever; the Narmada witnessed the creation of the world’s tallest mountains and our largest rift valleys. The river promises to flow on into the future as well. She is likely to flow on as long as the sky, the sun and the moon endure, because the Narmada is more than just a river. She is an elemental force of nature personified, the Great Grandmother of Rivers.

As our boat heads back to the shore guided by three teenagers, I remember the sepia portrait of the three boys splashing into the Narmada at the beginning of this book. What if they turned out to be the very saviors now guiding us back to the safety of the Narmada’s waters? The threat of impending danger also reminds us of Bhartrihari’s famous Nitishataka verse about exits and endings. Here is how Swami Vivekananda translated it: “O Mother Earth, Father Wind/Friend Light, Sweetheart Water/Brother Sky, here take my last salutation/With folded hands… I am melting away into Brahman,… cleansed of delusion/through the power of your good company.” O Maiyya Narmada, we would like to add, with folded hands, too.

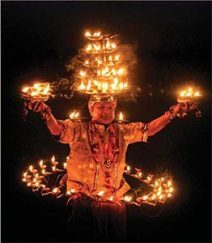

Hari Mahidhar is a celebrated photographer from India. He pursued press photography with a Hindi daily at the age of 22. Shifting to Mumbai, he became one of the world’s most sought-after industrial photographers. He has taken part in many group shows and held solo shows at Jehangir Art Gallery, Mumbai, in 2012, and at Fine Arts Gallery, Kolkata, in 2013. He has several books and catalogues to his credit, such as those of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (former Prince of Wales Museum); the Air India art collection and Churches of Goa. He is brand ambassador for Sony India.

Vithal C. Nadkarni has worked as a senior editor and columnist with The Illustrated Weekly of India, The Times of India and The Economic Times. He is a recipient of the Washington DC-based Alfred Friendly Press Fellowship and is a fellow of the London-based 21st Century Trust. The Serpent Within, a collection of his writings, is jointly published by CSIR and Wiley Eastern. He is deeply interested in classical music, art and Indian culture. He avidly practices yoga and is working on a monograph on icons of peace from the folk bronze tradition of India.