Andrew Niccol interview: Anon, privacy, My Little Pony

We talk to the director of Gattaca about his latest sci-fi thriller Anon, and how it ties into a modern world of Google and Facebook...

Writer-director Andrew Niccol is literally on the edge of his seat. As part of the round of publicity for his latest film, Anon, the marketing types have arranged an unusual interview venue: a spacious downstairs room in a Soho hotel, where another journalist is chatting to actor Clive Owen in another corner, as other assorted PR people mill in and out.

We mention all this because it has a bearing on the conversation that follows: with so much background hubbub, our chat with Mr Niccol took on an almost conspiratorial air – the director quietly, thoughtfully sharing his opinions on everything from his own work to Google’s mysterious alogorithms.

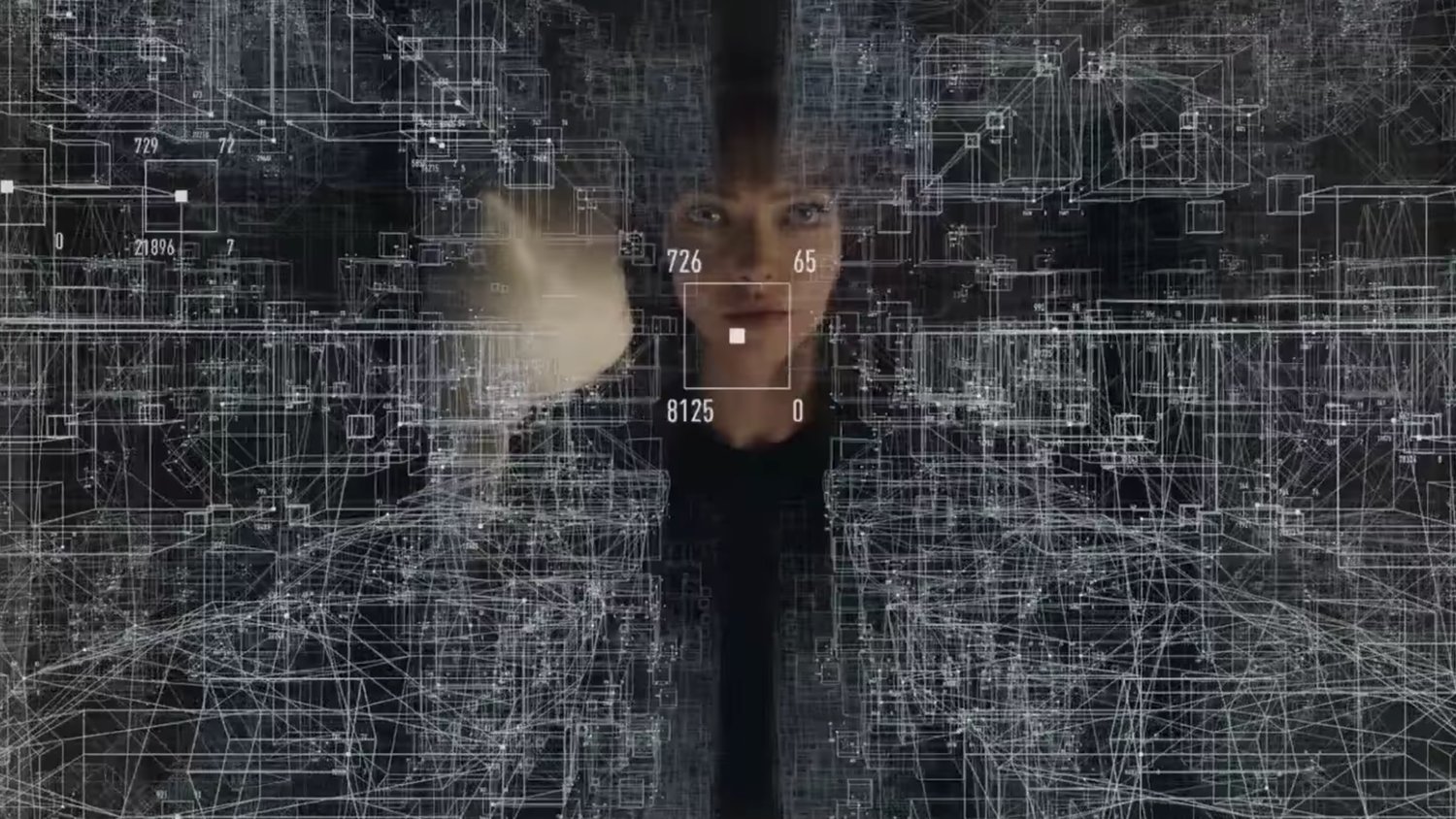

Maybe the setting was appropriate, because it’s a stark contrast to the film itself. In Anon, the smartphone tech we enjoy today has moved from our hands to our heads: something called the Mind’s Eye creates an advanced form of augmented reality, where everything from a passing businessman’s age and occupation to an advert for a games console are projected onto the world our us. It creates a world of eerie calm and quiet – with information at everyone’s fingertips, there’s no need for the chatter and chaos we see in other dystopian sci-fi films.

What disrupts the order of Anon’s world, though, is the presence of a killer who can hack into the Mind’s Eye tech, allowing them to commit murder and exit the scene without leaving a trace of their presence. This leads a detective, played by Clive Owen, on the path of a character known simply as The Girl (Amanda Seyfried). Could she be the killer?

Niccol’s no stranger to exploring the light and dark sides of current and future technology, having previously written The Truman Show (directed by Peter Weir) and Gattaca, In Time and Good Kill (which Niccol directed and wrote). With Anon, though, Niccol explores a particularly current topic in the media: how much information we give away through our excursions through the internet, and what that means for our individual privacy.

Here’s what Mr Andrew Niccol had to say…

There’s an overriding image from this film that’s still in my head: the city being so quiet and empty, because everything’s become internalised.

Right, exactly. It actually became a slight nightmare for me, because I realised that, because all signage, all advertising, is in your mind’s eye – so it’s basically in your head – I had to remove all signage from the actual world. So I physically and digitally removed all signage, all advertising. If you look back, you won’t see any street signs or anything.

I noticed, yeah.

The odd thing was, there’s one scene in New York, where he [Sal, played by Clive Owen] is walking down the street, and there’s a parking lot, a sign for the parking lot. So I physically removed the parking lot sign. Then when I’m looking through his point of view, there’s still a parking lot there, so I had to put in a digital parking lot sign in his mind’s eye, if that makes any sense! [Chuckles]

So I took the sign away, but then added the sign back in a different form.

It’s an interesting idea, because in science fiction, we’re used to seeing these futures where everything’s cluttered and overwhelming. So was that one of the first visual ideas you had as you were writing the script?

Well, it all follows the story, because, why would you go to the trouble of putting up a sign if, when you turn your head, it’s already there? And I wouldn’t have to physically change the sign – I could just change it in your human user interface, as we called it.

Did you do a lot of research into how that technology could potentially work?

In a way, you don’t have to research it, because it’s happening right now. As soon as you go outside in the street, people are going to be on their phones. If you’re in a restaurant, on a bus, that’s what’s going to happen. So all I’ve done is improve the technology – so instead of the ugly device, which you have to hold, I’ve just incorporated it [into the user’s head].

In fact, there used to be narration at the beginning of the film that set it up and explained what was happening. But I realised that I didn’t need it, you know? I just took it away because everyone’s gonna get it immediately – and they did.

I’m guessing you’d already finished this film when the stuff about Facebook emerged, but it’s interesting how that put the concerns you raise front and centre.

Yeah. I’ve always wondered why we’ve given away our privacy for nothing – well, actually, for convenience. I started to think about this false choice that we’re given: “If you have nothing to hide, you have nothing to fear”. That’s the mantra, right? But it’s more for me what The Girl [played by Amanda Seyfried] says, which is, “It’s not that I have something to hide, I just have nothing I want you to see.”

There are some people who, to varying degrees, want to give away everything. And there are other people who are more introverted, and they don’t. But I think we’ve given away the shop.

There’s a bit of a war for information, too. Because on one hand you have corporations who want our data so they can sell us things, and then you have the state, who want it for their own reasons.

Right. It’s almost become a cliche now, but you pay nothing for Google, you pay nothing for Facebook, so that means you are the product. That’s the thing. I have a friend who works at Google – he’s a big deal at Google – but he has a daughter. She loves this toy called My Little Pony. He gives her his phone, and she starts looking up My Little Pony, and of course, as soon as she gives it back, he’s constantly getting ads for My Little Pony.

As you’ll know from coming from here, you’ll suddenly get ads for things in Soho – seriously, because of geotagging. So he goes to the office, to Google headquarters, and says, “I’m getting all these [My Little Pony] popups. Can you get rid of it for me?” And they said, “No. The algorithm’s too strong. It’s gonna have to die a natural death.”

So even though he’s a big deal at Google, he can’t get into the algorithm and change it. He’s just gonna have to live with it! [Laughs]

That’s disturbing, isn’t it? I do read things where some of the higher-ups at tech companies don’t even use their own products. Like some people at Twitter and things like that.

It’s interesting, because [at Google] they have a sign there that says, “Do no evil”, right? If you put that sign up, it means… there’s a studio in Hollywood where, in their lobby, they have photos of directors who work at the company, to try to make it seem like they’re director-friendly. Actually, it means they’re not director-friendly! [Laughs] Similarly, that sign means that Google is doing evil.

Do you have a Gmail account?

Yeah.

Okay. So you know all of your emails are being read. Right? They know so much about you. Probably, in a weird way, more than you know about yourself, just from your browsing habits and things like that.

Well, that’s what the Cambridge Analytica controversy threw up: the potential for a company to know more about voters than they know about themselves.

I like how Google knows when you’re having an affair. [Laughs]

What it is is that, my phone is in a hotel at 3AM in the morning, geotagging, next to a phone of a woman who is not my wife. There is no reason for that other than, I’m having an affair. [Laughs]

Do you think what your film portrays is an inevitable outcome, or is it just one possible future? For example, the writer Lionel Shriver said today that she thinks social media will fall out of favour with millennials.

Well, Facebook already has in a way. You know, even my own kids don’t have Facebook. But if you’re on Instagram, it’s owned by the same company. I think we’ll see companies [come and go] – like Yahoo, that’s not so fashionable now, but others are more fashionable. They just move onto a different name – Snapchat, whatever it is.

But you don’t think there’ll be a collective movement away from that kind of online sharing.

I don’t know. I don’t know if there’ll be a backlash. I mean, I’m not on social media, for a few reasons [chuckles]. One is privacy, but the other is that it doesn’t really help me. I mean, why would I go on Twitter? If I’m writing, I want to get paid! [Laughs]

Fair enough!

But I don’t know whether there’ll be a backlash like The Girl’s. Maybe that offers some hope in a weird way, because that’s what she’s doing. She’s using these counter-measures. So maybe she’s the hope.

Your films, even Good Kill, which was set slightly in the past, if you look at them together, they create a quite dystopian outlook.

Yes, that was absolutely… I researched [Good Kill] to death. They even use that now, weirdly, in the drone programme, as orientation training.

That’s interesting. I didn’t know that.

When I researched it, there were things that I couldn’t put on film because people would think they were ludicrous. Some of the guys, who would work a 12-hour shift killing the Taliban with a joystick, would go back to their Vegas apartment and play videogames. [Laughs] That’s too much even for me!

That is pretty dark. But what I meant to say was, your films create a dark impression of where we’re collectively heading. Do you think you’re optimistic, though, as a writer?

I don’t think I’m optimistic or pessimistic – I hope I’m realistic. The thing about technology is that it isn’t all good or all bad – it just is. It’s really how you use it or don’t use it. I don’t think there’s any technology that we’ve invented that we’ve later destroyed. So we aren’t going anywhere – we aren’t going backwards. You know?

So I think that’s really what I write. Sometimes they’re cautionary tales.

Going back to Gattaca, The Truman Show, Good Kill... a lot of your films deal with a sense of voyeurism in some way. I wonder if that’s something that interests you as a filmmaker, or whether it’s a natural…

[At this precise moment, Clive Owen walks over and says:]

Clive Owen: Don’t believe a word he says. That’s all I’m saying. [Laughs]

Andrew Niccol: He’s onto me!

Yeah, there is a voyeuristic element. In a weird way… you were talking about Good Kill, and I wondered why I made it, and why I was interested in it. Then I saw an article about it, and it said, “More Truman Show than Terminator“. And I think that’s why. But yes, there is something about that god’s eye point of view that I explore. I don’t like to analyse what I do, but you’re right! I’m probably a voyeur.

You were saying about Good Kill being used in orientation training, but also Gattaca was cited a lot by scientists…

Yeah. I’m always drawn to the ambiguities of life. And that’s a classic: you cure a genetic disease, and that’s fantastic. And then you can enhance someone. So you can cure a person, and also enhance a person. But in enhancing, are you losing something of their essence? Their individual essence as a human being? The essence of what they were going to be – you’ve tampered with it. Do you know what I mean?

There are plenty of cases. Stephen Hawking is a classic case: would he have had the thoughts he’d had without that disease? If he was completely mobile, would he have been drawn to other pursuits? You would have looked in the petri dish and said, “Hmm, let’s fix that.” But when you fixed it, what else did you do? Did you lose a brilliant mind? I think about things like that. But it’s all grey to me – it’s like I say, we can use it or abuse it.

I guess rather than being optimistic or pessimistic, what you’re saying is technology is transactional: for the things we gain, we lose something.

Did you read lately about GPS? It’s changing us. Because we rely on GPS, we’re losing our innate ability to navigate our world. Which is very interesting to me, because that means there’s something that was special about us that we’ve discarded.

There’s another thing. It’s a trivial thing, but I see my daughter’s always on her iPad, and she looks down a lot. Kids, very young, get a crease here in their neck, because of the angle of what they’re watching. It’s a trivial example, but I think, as you say, there are costs.

And I suppose the internet’s still new enough that we don’t yet know how it’s changing our minds. Like the GPS thing, and like being able to search for things on Google affecting our recall.

Sure. And then there’s the cost to book stores. Book stores are dying. You used to go to a book store because you were interested in a book. But the benefit you got were all the books you weren’t interested in that you turned and saw. You don’t do that now. You only look at the books you want, that you think you’re interested in. You don’t get to see the ones that you didn’t know you’re interested in, if you understand. It’s a funny way of saying it, but…

No, I know what you mean. And talking to you, it doesn’t sound to me as though you’ve tired of writing about technology or science fiction as a subject.

There are a couple of things. It’s not that I’m drawn to it – it’s coming at me. You don’t have the benefit of knowing what my filmography would be… it’s about what the guys who write the cheques are drawn to. You don’t get to see the movies I wanted to make and didn’t, because they’re all, “He does sci-fi.” So maybe I would’ve made more contemporary films.

I see. Finally, then, are there any films you’d recommend people watch after Anon? As a double-bill, say?

Oh. That’s an interesting question. I’d say The Conversation!

Good choice. Andrew Niccol, thank you very much.

Anon is out in UK and Irish cinemas and on Sky Cinema from May 11.