VANCOUVER -- The powerful opioid fentanyl, recently linked to an outbreak of overdose deaths in Western Canada, appears to be flowing along a well-worn drug trafficking route -- killing some of its users in the same way tainted ecstasy did before.

Authorities theorize the potent painkiller is being imported from Asia to the West Coast, then moved to the black market in B.C. and Alberta by organized crime groups.

Policing has largely centred around public warnings and education campaigns to prevent overdoses, while investigations are at such an early stage that officers haven't yet uncovered any pill manufacturing operations.

It's a pattern reminiscent of early 2012, when investigators were probing the source of batches of ecstasy mixed with an unknown, lethal additive as deaths stacked up.

"I think there is something of a trade route, and it's one we saw in place at the time of ecstasy-lacing," said Simon Fraser University criminologist Rob Gordon.

Over the past two weeks, police in Metro Vancouver have linked four overdose deaths to fentanyl. Authorities and health officials say that many using the drug don't know what they're taking.

Fentanyl produces a euphoric high and pain relief, while overdosing can cause blood pressure to plummet, slowed breathing, deep sleep, coma or death.

A couple in their early 30s died in their North Vancouver home on July 20, while a 17-year-old boy and 31-year-old man each died separately last weekend.

It's believed the victims either thought they were taking OxyContin, or using illegal drugs spiked with the fentanyl, said Jane Buxton, at the B.C. Centre for Disease Control.

More than 500 people have died under similar circumstances across B.C. and Alberta since 2013, with a spike in the past year.

Fentanyl's debut on the underground market was largely related to a manufacturing change that prevented OxyContin from being crushed for snorting or smoking, said a spokesman for Alberta's ALERT integrated policing unit.

Mike Tucker said that opened a void that crime bosses began exploiting, by selling fentanyl as fake OxyContin or heroin -- yet it's up to 100 times more toxic than morphine.

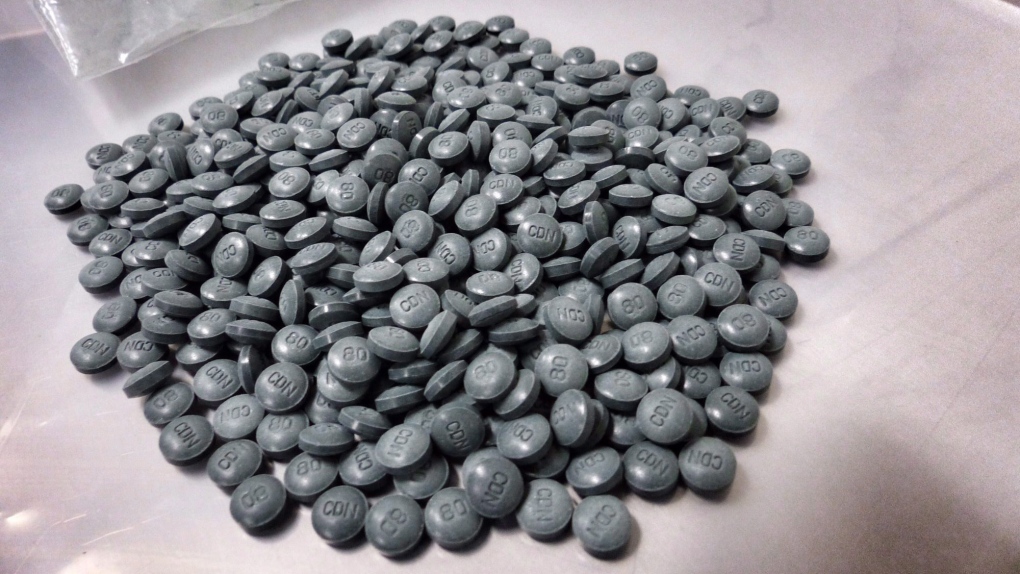

Much of the supply is believed to originate from China and possibly Turkey as a cheap raw powder that gangs in Canada press into pills, he said. It lands on the streets in a form known as "fake 80s" or "greenies."

The drug's appearance is new enough that investigators are still digging to reach the root of distribution channels, said Tucker.

"I would guess that most of the fentanyl we're seeing is coming from British Columbia, and that could be a stop on a shipping route or something," said Tucker, noting ALERT seized 18,000 pills in 2014 compared with no seizures the year earlier.

"We still don't know enough about the sources."

But police do say multiple gangs are involved and they're cashing in on low production overheads, said Sgt. Lindsey Houghton, with B.C.'s Combined Forces Special Enforcement Unit.

"Fentanyl is not being made here, it's being made elsewhere ... then coming to here and then it gets into the hands of the people who mix it in their bathtub and put in some blue dye or green dye and get a pill press and make it into fake Oxy," he said.

Pills can sell upwards of $50 to $100 on the street in some communities, he added.

"You can make a lot more money mixing fentanyl in with (other substances) than trying to sell heroin or coke."

Tucker said the pills wholesale in Alberta for about $12, but can be sold on the street for anywhere from $25 to $80.

Some busts have revealed possible cross-provincial networks of operations.

In March, ALERT warned fentanyl was being shipped from Alberta to B.C. and Saskatchewan using hidden compartments inside sport utility vehicles.

Gordon said the drug is flowing along the traditional north-Pacific trade route that's shared by other drugs like ecstasy and marijuana.

"There are well-established close ties between groups in Alberta and groups in B.C. with respect to the illegal drug trade. They may even be the same people," he said.

The RCMP is co-ordinating investigations at a national level.

Buxton said a new study, plus anecdotal evidence from recent deaths, points to the likelihood people dying don't know the source of their high.

"It's so cross-cutting, from your healthy, sporty teenager to a couple with a young child, to people who are using drugs regularly."