iBet uBet web content aggregator. Adding the entire web to your favor.

Link to original content: https://www.chesshistory.com/winter/extra/golombek.html

Edward Winter

See C.N. 5168 below.

The present (general) article complements Harry Golombek’s Book on Capablanca.

The longest letter we ever received from Harry Golombek was in the summer of 1985, and before reproducing it we summarize the context.

Regarding the anti-Semitic articles attributed to Alekhine, C.N. 990 included some comments to us from Anthony Saidy about two books by A. Kotov and M. Yudovich, The Soviet School of Chess (1958) and The Soviet Chess School (1983):

‘Whereas in 1958 no mention was made of the sticky subject of Alekhine’s petty collaboration with the Nazis in the form of those anti-Semitic essays which I believe were written so ludicrously as to telegraph their insincerity, now we learn that he was “unjustly accused of collaboration”. I believe this exculpation to be the most transparent rewriting of history for the hackneyed Soviet ideological purposes. When I pointed out to Kotov at Nice in 1974 the fact that a leading British figure had, after Alekhine’s death, found a version of the essays in his handwriting (where are they now?), thus proving their authenticity, if not their plausibility, he brushed it off as “British propaganda”.’

The vague term ‘leading British figure’ was used because, at that time, it was uncertain whether it was B.H. Wood (the name originally given to us by Dr Saidy), Golombek or someone else. We decided to raise the matter with H.G. As will be seen below, he not only replied regarding Alekhine but also commented briefly on another item in the same issue of our magazine (C.N. 1007), in which Hugh Myers had presented a three-page analysis of the termination of the first Karpov v Kasparov match and had come to conclusions sharply at variance with the prevailing view at the time.

‘From Harry Golombek

Albury

35 Albion Crescent

Chalfont St Giles

Bucks HP8 4ET.7 July 1985

Dear Mr Winter,

Many thanks for your kind note and for sending me issue 22 of C.N. However I must add that Mr Myers’ intervention in the Karpov-Kasparov dispute seems a little unhappy since he merely adds a little confusion to the whole unhappy incident about which he seems to have little first-hand knowledge.

The statement in The Times that I am fully on the mend is a little premature but it’s a little better than the previous bald statement that I was ill in hospital.

As a matter of fact the position is that my health is improving and that I must be thankful to my ancestors for bequeathing me a very strong heart capable of standing quite a lot of strain.

In addition the fact that I have never smoked and have drunk very little alcohol seems to have stood me in good stead as regards my major organs ...

[Here we omit about 300 words of personal/medical details.]

You will see by all this that I am a walking compendium of illnesses; but I’m determined to survive as I have at least five more books to finish writing and a great deal of Mozartian chamber music to which I want to listen.

Meanwhile a little clarification about the discovery of the Alekhine articles.

When Alekhine’s widow died Brian Reilly was in Paris and he was afforded the opportunity of examining her effects. When he returned from Paris he said to me sadly, “It’s true about the Alekhine anti-Semitic articles. I’ve seen them in Alekhine’s own handwriting”.

However, I should add that Reilly, who is writing a definitive biography of Alekhine and for whom Alekhine seems to have become a sort of chevalier sans peur et sans reproche, said to me a few months ago, “Where did you get the information in your article in your encyclopedia about Alekhine having written the anti-Semitic articles?”

Upon my telling him that I had got the information from him on his return from Paris, he denied that any such conversation had taken place. So you have to take your choice; either my memory is right (and I can still see in my mind’s eye Brian’s melancholy face as he told me this) or Brian’s memory is right and this never took place. I must add that most people find my memory is all right; nor do I experience any difficulty in remembering the appropriate facts for writing an article about something about 20 years ago.

However, you had better stick to a leading chess figure, which phrase can hardly be confused with such a character as Myers or B.H. Wood.

Meanwhile I intend to test my stamina and my memory and my chess skill by playing in the British veterans championship tournament at Edinburgh next August.

If I ever fully recover my health I intend to pay another visit to Geneva since I’d like to have another look at Mme de Staël’s beautiful house there and in that case I’ll pay you a visit in 9 rue de la Maladière; such a place should seem quite fitting for one who is a walking compendium of illnesses as I am and as I hope you are not.

Yours unhealthily but sincerely,

(signed) Harry Golombek.’

One point arising from this letter is Golombek’s reference to having ‘at least five more books to finish writing’. We are not aware of his having published any (new) books after 1985.

(3605)

A quiz question in C.N. 272:

About whom did Harry Golombek write: ‘There is about his best games a sort of resilient and shining splendour that no other player possesses.’?

The answer, in C.N. 319:

Two or three readers replied, ‘Himself’. Shame on you. The answer is Zukertort (in the Encyclopedia).

Harry Golombek’s The Encyclopedia of Chess states that Nottingham, 1936 is ‘still the only tournament to have included five past, present or future world champions’.

Michael McDowell (Newtownards, Northern Ireland) reacts as follows:

‘Has no-one ever pointed out that the Alekhine Memorial, Moscow, 1971 and the 41st USSR Championship, Moscow, 1973 both had the five champions Smyslov, Tal, Petrosian, Spassky and Karpov participating)?’

We can answer Mr McDowell on the Alekhine Memorial: indeed it has been pointed out before, by Bill Hartston. And where was he writing? In Golombek’s encyclopedia.

(285)

An endnote on page 265 of Chess Explorations mentioned that a book purportedly by Karpov also overlooked the two events, in both of which he participated. See C.N. 1027 in Karpov’s Writings.

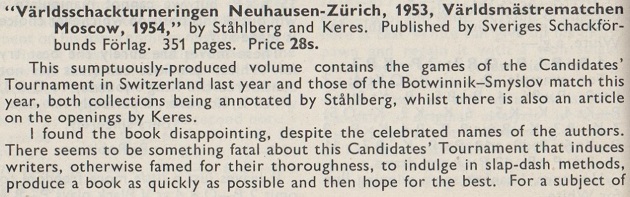

An extract from C.N. 601 (see Book Notes):

‘Golombek’s Encyclopedia of Chess falls into careless error in its cursory ten-line entry on Max Weiss (page 342) when it states: “His books (Schachmeisterstreiche, Mulhausen 1918, and Kleines Schachlehrbuch, Mulhausen 1920) as well as his problem collections (of Loyd, Shinkman, and of Bamberg Problemists, Caissa Bambergensis, Bamberg 1902) are forgotten today.” The afore-mentioned books do indeed owe their authorship to one Max Weiss – but the all-too-fallible Encyclopedia confuses its Viennese subject with one Max Weiss of Bamberg (Germany)!’

So wrote Warren H. Goldman on pages 24-25 of his fine book Vienna, 1890. The same C.N. item also gave this comment of ours:

True enough, though it might have been added in fairness that the erroneous bibliography was at least removed from the Penguin edition of Golombek’s work.

Chess, The History of a Game by Richard Eales (Batsford) is a concise, well-written summary of current knowledge, though not really the work of outstanding original research promised by the blurb. The early chapters are particularly well handled, while we detected a certain thinness in the coverage of the period circa 1850-1950, accentuated by the fact that the author is considerably stronger when writing about trends than about individuals.

Although general comments on Murray are complimentary, H.J.R.M. is frequently criticized on specifics. Golombek’s 1976 history, beautifully produced but marred by the author’s own over-obtrusive personality, is not given very much acknowledgement.

Eales is careful about his facts, although we did note the following: misspelling ‘MacDonnell’ (e.g. page 132); page 153, Lasker did not become a doctor in 1902; page 153, Lasker played four, not three, tournaments in the period under consideration. Page 161: Marshall did not become US Champion in 1906. Page 194: FIDE’s motto is misspelled.

In addition there are many statements which are, at the minimum, debatable, while certain historical references, such as the Glasgow Herald one on page 156, arouse suspicions about Eales’ well-rounded knowledge of the game’s history.

In general, though, a carefully prepared book, the hallmarks of which are clarity and common sense.

(878)

Regarding From Baguio to Merano by A. Karpov and V. Baturinsky (Oxford, 1986), C.N. 1322 (written in 1987) concluded:

One final note on this book (which, incidentally, is exceptionally well proof-read): it contains the allegation that Harry Golombek and Murray Chandler helped the Korchnoi camp by regularly analyzing adjourned games. Denying this in the BCM of December 1981 (page 513), Golombek expressed the hope that Karpov’s work would be translated and published in England ‘so that I can proceed to sue him for libel’. Now we shall see.

See also Anatoly Karpov.

C.N. 889 quoted from page 94 of The Literature of Chess by John Graham (Jefferson, 1984):

‘Golombek was born of Russian parents and speaks Russian well.’

The book had what we termed ‘an ill-considered complimentary Foreword written by H. Golombek.’

Below are our comments in C.N. 1081:

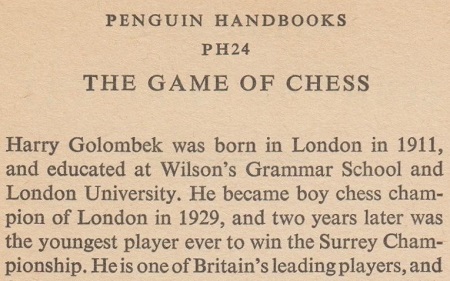

The July 1946 CHESS (page 226) states that Golombek was born of Polish parents, while the 1985 Who’s Who reports that he is the son of Barnet and Emma Golombek. The same Who’s Who describes H.G. as ‘Joint Editor, British Chess Magazine 1949-67’. Goodness only knows where that came from – certainly not from Golombek’s Encyclopedia, which correctly credits Brian Reilly with editorship – sole editorship – for the whole of that period and more.

On the subject of Golombek’s parents, see also C.N. 11824 below.

From the Summer 1955 Chess Reader, in which Ken Whyld reviewed Tartakower and du Mont’s 100 Master Games of Modern Chess:

‘It is curious to see once more the game Golombek-Brown, in which White wins by means of a neat but obvious piece sacrifice. From the excessive number of times it has been published, future generations must think it highly esteemed in our day.’

(1338)

Golombek had a longstanding difficulty in relating correctly the basic facts of Capablanca’s record, and C.N. 1406 shows how a concentration of errors remained in successive editions of another book of his.

On page 220 of The Game of Chess (Penguin) Harry Golombek writes of Capablanca: ‘In 1905 he beat Marshall by +8 –1 =14; in 1919 he beat Kostich 5-0; in 1921 he won a world championship match against Lasker by +4 –0 =14 and in 1932 he beat Euwe by +2 –0 =8.’

a) for 1905 read 1909; b) for =14 in the Lasker match read =10; c) for 1932 read 1931. We pointed out this concentration of errors on page 11 of the October 1976 CHESS, but no corrections were made in the third edition of the book (1980, reprinted 1986, page 222). Nor is the right information given in the French translation of the book (published by Payot).

The back cover of the latest Penguin edition says that since 1954 The Game of Chess ‘has sold over a million copies and the text has been revised and updated’.

(1406)

Andreas Keller (Berne, Switzerland) writes:

‘There seems to be an inaccuracy in H. Golombek’s book The World Chess Championship, 1948 which is not mentioned in the foreword to the 1982 BCM reprint. At move 42 in the 11th-round game between Smyslov and Reshevsky the following position was reached:

Golombek states that play went: 42 Kg3 Kf8 43 f3 Ra1 44 Kf4 a2 45 e5 Kg8 46 Kf5 Rf1 47 Rxa2 Rxf3+ 48 Kg6 Kf8 49 Ra8+ Ke7 50 Ra7+ Resigns.

However, the tournament books by Euwe and Keres, as well as Smyslov’s autobiographical collections, give: 42 Kg3 Re2 43 Kf3 Ra2 44 Ke3 Kf8 45 f3 Ra1 46 Kf4 a2 47 e5 Kg8 48 Kf5 Rfl 49 Rxa2 Rxf3+ 50 Kg6 Kf8 51 Ra8+ Ke7 52 Ra7+ Resigns.’

(2072)

Werner Kühne (Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany) sends a copy of the Russian bulletin of the world championship match-tournament, Na pervenstvo mira, 15 April 1948, No. 9, page 5. This, together with several other sources, would suggest that Golombek’s version of the final moves of the game between Smyslov and Reshevsky was incorrect.

(2110)

It may be wondered who first suggested the concept of zonal tournaments. Here is an extract from Harry Golombek’s review (BCM, June 1940, page 201) of Um die Europameisterschaft. Der Schachwettkampf Euwe-Keres by J. Hannak (Kecskemét, 1940):

‘Dr Hannak outlines an idea for solving the world championship problem by dividing the chess world into zones in similar fashion to the Davis Cup. Hence, the significance of the title of the book For the Championship of Europe.’

(Chess Café, 2001)

An arraignment by Harry Golombek on page 7 of the January 1939 BCM, i.e. the opening paragraph of a review of Lehrreiche Kurzpartien by J. Benzinger (Leipzig, 1938):

‘This book contains a collection of 172 brief games only about four of which ever deserved to be seen in print. The rest are feeble examples of third-rate chess. Miniature games of chess should resemble miniature paintings; they should be delicately varied, subtly designed and, above all, executed with economy. But these are gross, heavy and thick with accumulated blunders, in short the book is a chamber of horrors which contains but little of the edification promised in the title.’

(2401)

A news report by Harry Golombek on pages 8-9 of the January 1952 BCM:

‘My more mechanically minded readers will be interested to learn that a portable electronic brain, weighing a mere 500 pounds and costing only 80,000 dollars, has been developed by the Computer Research Corporation of Hawthorne, California. One of its designers, Richard Sprague, claims it can play unbeatable chess. Donald H. Jacobs, president of the Jacobs Instrument Company of Bethesda, Maryland, and himself developer of a 140-pound mechanical brain, proved sceptical and challenged the CRC-102 (the euphonious and imaginative name of the electronic midget brain) to a best of 20 games match, offering to bet 1,000 dollars on his ability to defeat the baby electronic brain without consulting his own mechanical brain for assistance. The CRC-102 declined the match hastily on the grounds that the “urgency for this machine in the defence effort makes such a tournament untimely”. Clearly history is engaged in its habitual process of repeating itself and we are faced once again with the Morphy-Staunton incident.’

(2646)

The device in question was discussed on page 34 of Chess Review, February 1953, where Robert H. Dunn quoted the following:

From a report by Harry Golombek on the seventh game of the Botvinnik v Smyslov world championship match in Moscow on 30 March 1954:

‘Television made its first appearance in the history of world chess championship matches during the course of this game, which was televised from 8 till 8.30 p.m.’

Source: BCM, May 1954, page 141.

(2655)

‘One shudders to think what FIDE would have been without him.’ That was Harry Golombek’s verdict (BCM, December 1970, page 345) when Folke Rogard retired as President of the governing body and handed over to Max Euwe. Golombek also commented that the choice of successor ‘was unanimous and certainly no better man (or even as good) could be found to fill the place vacated by Folke Rogard after 21 years’ magnificent service in this post’.

Following the Swedish lawyer’s death in 1973, H.G. wrote an obituary in The Times which also appeared on pages 513-514 of the December 1973 BCM and, with some amendment, on page 277 of his Encyclopedia of Chess (1977). However, a detailed factual assessment of chess administration during the Rogard decades has yet to be written, and perhaps never will be. The task would be uncommonly difficult, and nowadays even Rogard’s name seems known to few.

(2725)

An assessment of Tartakower by Harry Golombek (BCM, March 1956, page 71):

‘He was a man who never committed an underhand action and who was more truly honest than anyone I have ever met. Sincerity and generosity were two marked features of his character and made me trust and revere him.’

(2990)

Below is a news report from page 292 of the October 1960 BCM in which Harry Golombek’s waspishness and sniffy irony were in full flow:

‘The US is experiencing difficulty in raising the sum necessary to send a team to Leipzig. A chess committee has addressed an open letter to President Eisenhower stating that 6,000 dollars were required for this purpose and that “this year with such top players as Bobby Fischer, Samuel Reshevsky, Larry Evans, Robert Byrne, Arthur Bisguier, Pal Benko, Nicolas Rossolimo, James Sherwin and others to select a team from, our chances of winning are excellent”. The letter finishes with “We need an immediate O.K. from you”. One hopes that there will be a good response to this request and that we will see a US team at Leipzig. Unfortunately, the game of chess being what it is, we doubt whether even an immediate O.K. from a US President will suffice to lever the team into first place.

This optimism about USA’s chances seems to flow in some measure from the considered opinion of the US Champion, 17-year-old Bobby Fischer. In the Saturday Review for 10 September we read that “the big news in American chess these days is that the United States, for the first time, has at least half-a-dozen players who, as a group, have a better than fair chance of winning the world’s championship at the Chess Olympics. According to young Mr Fischer, who visited S.R.’s offices recently, a team made up of himself, Samuel Reshevsky, Larry Evans, Nicolas Rossolimo, Arthur Bisguier and Robert Byrne would be in genuine contention for first place.” Knowing the members of this team the present writer would be prepared to admit the truth of this last sentence, always provided the last three words were omitted.

Some more illuminating remarks are quoted in the following paragraph: “We asked Fischer about his recent trip to Russia and he told us that the average man in the street was no more interested in chess there than he was over here. ‘Moscow’s a pretty dull place’, he told us frankly. Fischer himself has grown up some since we talked to him last, but mostly in height. He is still not much of a scholar, although he likes books on magic, hypnotism and palmistry, and stories of intrigue. Asked if he wanted to go to college, he shook his head. ‘Nah’, he said, ‘too much homework.’”

What sort of divining guide Fischer used to test the average Muscovite’s interest in chess we do not know since he speaks no Russian but we are happy to assure the reader that the young American grandmaster is far from being the moron that one might think him to be from these idiotic remarks.’

(3022)

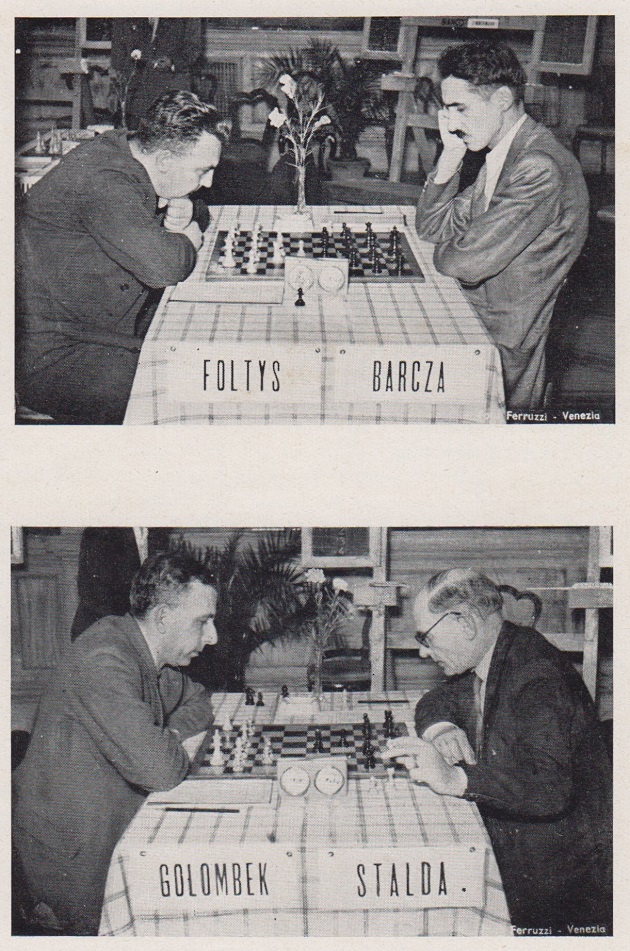

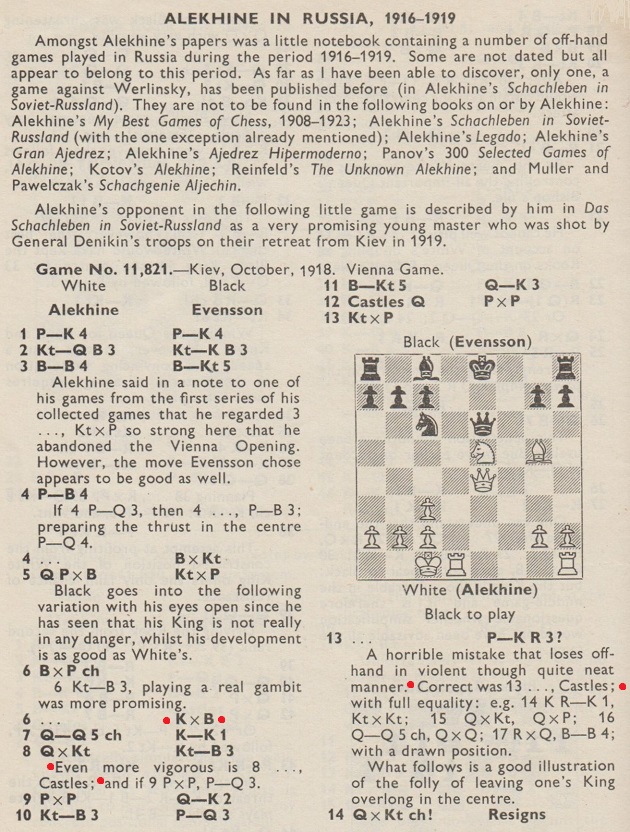

The reference to Barcza in C.N. 3098 (see Chess Jottings) has reminded Steve Giddins of what Wolfgang Heidenfeld wrote on pages 106-107 of the April 1962 BCM regarding the start of Barcza’s game against Ólafsson at that year’s Interzonal tournament in Stockholm:

‘1 Nf3 g6 2 d4 (Unusual – for Barcza.) 2…Nf6 3 g3 (Normal – for Barcza, who still relates with pride Golombek’s remark on his opening repertoire. “Barcza”, Golombek is reputed to have said, “is the most versatile player in the opening. He sometimes plays P-KKt3 on the first, sometimes on the second, sometimes on the third, and sometimes only on the fourth move.”)’

Mr Giddins asks if any corroboration exists for Golombek’s alleged observation.

(3242)

Regarding Harry Golombek’s book on the 1948 world championship match-tournament in The Hague and Moscow, the following untrue statement is quoted on page 42 of the December 2004 Chess Life:

‘The author of this book was on the spot throughout and at the very epicenter of all the action.’

In reality, Golombek was not present in Moscow at all, as he explained in his introduction to the 1982 BCM edition of the book:

‘The time came when the event moved off to Moscow. I endeavoured to follow the big group of Dutch and Russian chess masters and officials but was unable to gain a visa. [H.G. then gave further details.]

So I had to be content with studying the games of the Russian section of the tournament in the Soviet bulletins. Fortunately, these were very well annotated and there were also quite elaborate descriptions of the playing hall and the various circumstances that attend a great tournament.’

(3482)

Regarding the above reference to page 42 of the December 2004 Chess Life, C.N. 3864 added that the untrue statement about Golombek, unquestioningly quoted by Larry Evans, had been written by Raymond Keene.

It has yet to be ascertained whether anybody has seen the cassette referred to in CHESS, July 1972, page 299 and quoted in C.N. 2787:

A chess programme in colour of 30 minutes’ duration has been recorded for television cassettes on a co-production basis between the Crown Television Group London and East End Productions in New York. It is based on Harry Golombek’s Penguin book The Game of Chess.

Harry Golombek

(3516)

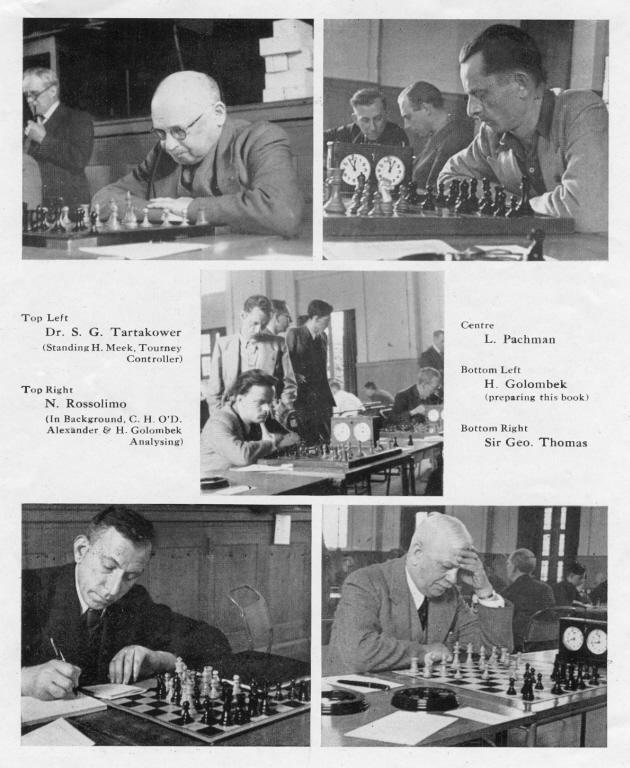

Some group photographs featuring Golombek are given in our feature article on Leonard Barden. See too the material concerning Golombek in Ernst Ludwig Klein and in Chess and the Code-Breakers.

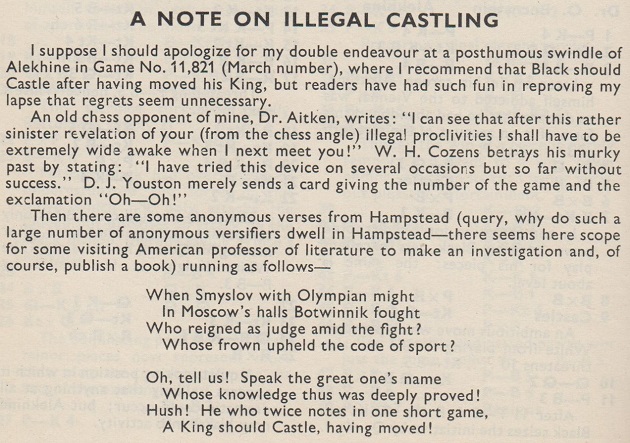

This caricature of Golombek, by Zen, is in III° torneo internazionale di scacchi Venezia 1949 by H. Müller (Venice, 1950).

(3657, 3664)

When was the term ‘grandmaster draw’ coined? On the first page of the Introduction to his book Prague 1946 (Sutton Coldfield, circa 1951) H. Golombek wrote: ‘the number of so-called “grandmaster draws” can be counted on the fingers of one hand.’ How much further back can the phrase be traced?

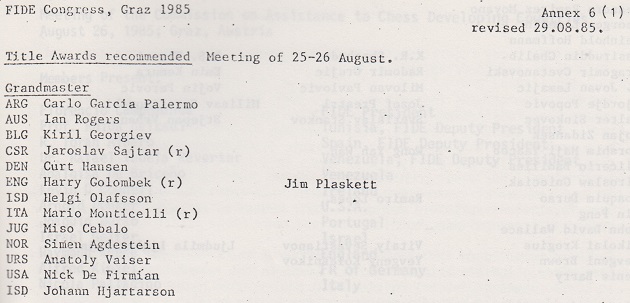

Below is an inscription by Golombek in our copy of Prague 1946 to the Czech master Jaroslav Šajtar:

(3803)

We have found some occurrences of ‘grandmaster draw’ from 1948 (i.e. a couple of years before FIDE officially brought in the title ‘grandmaster’).

In a report on the world championship match-tournament page 11 of the May 1948 Chess Review had two instances:

‘Round eight produced the first “grandmaster draw” of the tourney. On the 24th move, Keres proposed a draw and Reshevsky accepted.’

‘Many people feel that the “grandmaster draw” is the bane of competitive play.’

From page 308 of the September 1948 BCM (a report by H. Golombek on the Stockholm Interzonal tournament):

‘The Lilienthal-Bronstein game was a typical example of the so-called “grandmaster” draw.’

(6638)

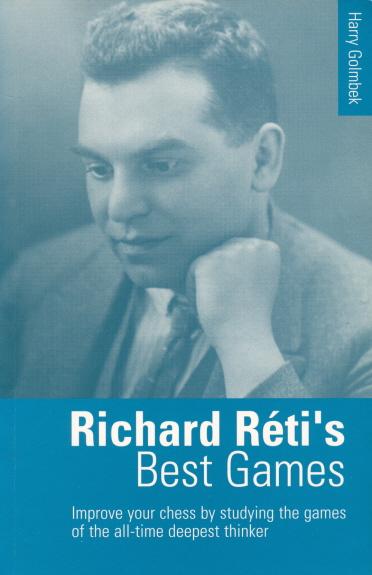

From a review by J.M. Aitken of Réti’s Best Games of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1954) on pages 100-101 of the March 1955 BCM:

‘Chess books (and, in particular perhaps, games collections) can be divided into two main classes – those that are the product of a genuine devotion of the author to the subject and those that are, in the main, made to order to meet a real or supposed topical demand. It is not intended to scorn or disparage unduly the second class; given a competent and conscientious author, an excellent book will probably be produced. Nonetheless, it is in the first category that the true masterpieces are likely to be found and it is high in this class that we must rate Golombek’s book on Réti. Réti has clearly always been one of Golombek’s chess heroes and now, like a more fortunate Antony, he comes not to bury Réti, but to praise him.’

Below is Golombek’s inscription in one of our copies of his book:

(4206)

C.N. 1054 reported on Eric Schiller’s 1985 book Grüenfeld Defense, Russian Variations, also published by Chess Enterprises, Coraopolis:

‘Grüenfeld is the novel spelling on the front cover. The back cover and spine prefer Gruenfeld. The Preface gives Grünfeld. The bibliography has Bruenfeld.’

That C.N. item noted too the book’s dedication (by Eric Schiller):

At least Harry Golombek’s name was spelt correctly. C.N. 2397 commented that:

‘... in 1997 Batsford produced a reprint of Golombek’s book on Réti, putting “Golmbek” on the frnt cver.’

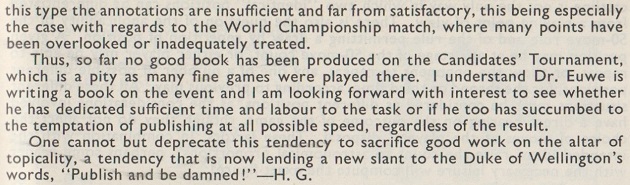

David Picken (Greasby, England) quotes the following from pages 47-48 of World Chess Championship 1954 by Harry Golombek (London, 1954):

‘Watching them today I was struck by the contrast between the players in their actual physical moving of the pieces. Smyslov invariably makes each move with a little flourish and a motion, as though he were screwing in each piece on the board. Botvinnik is strictly utilitarian in his methods. He shuffles the pieces into position almost negligently, as though he knows they will drop into the right place given the slightest encouragement – and so, it must be admitted, they usually do.’

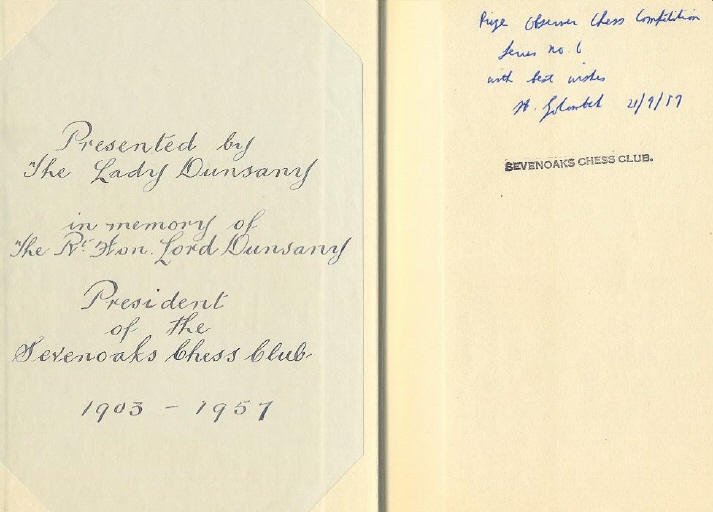

The inscriptions in one of our copies of Golombek’s book:

(4298)

From Pierre Bourget (Beauport, Canada):

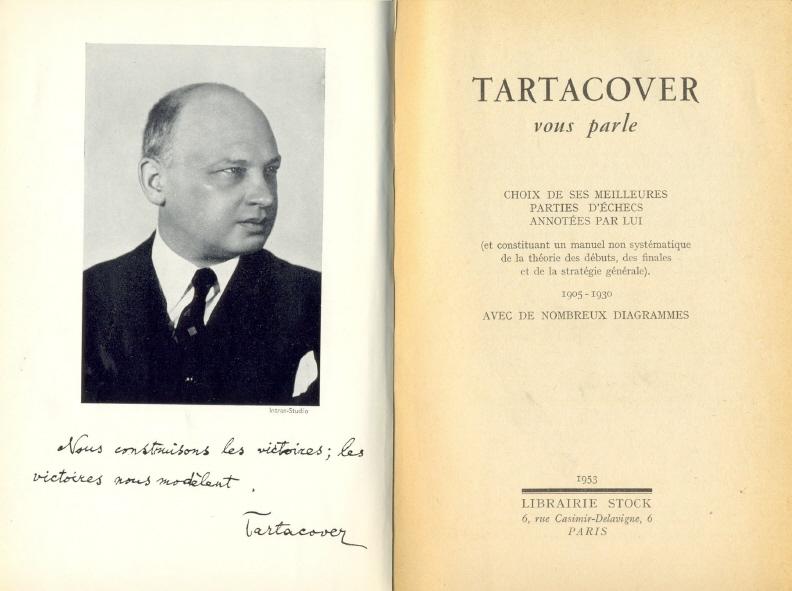

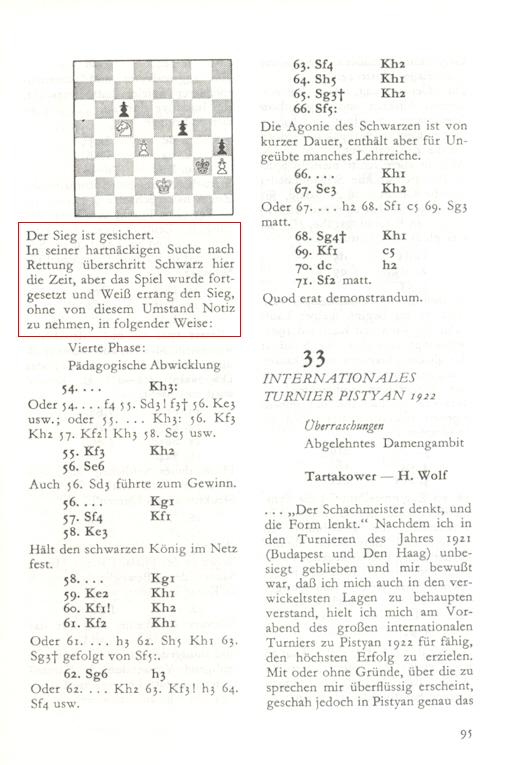

‘Tartakower’s My Best Games of Chess 1931-1954 was translated from French by Golombek, but I have never seen a book in French by Tartakower for that second period. I am aware of a French edition only for 1905-1930, under the title Tartacover vous parle.’

Tartacover vous parle was published by Librairie Stock, Paris in 1953 and is readily available today, having been re-issued by Payot, Paris in 1992. In common with our correspondent, we have no knowledge of a French edition on the years 1931-54.

Some further remarks may be added here. My Best Games of Chess 1905-1930 and Tartacover vous parle are not identical. Most notably, the French book had four additional Tartakower games, against Alapin (Munich, 1909), Wolf (Vienna, 1922), Golmayo (Barcelona, 1929) and Font (Barcelona, 1929).

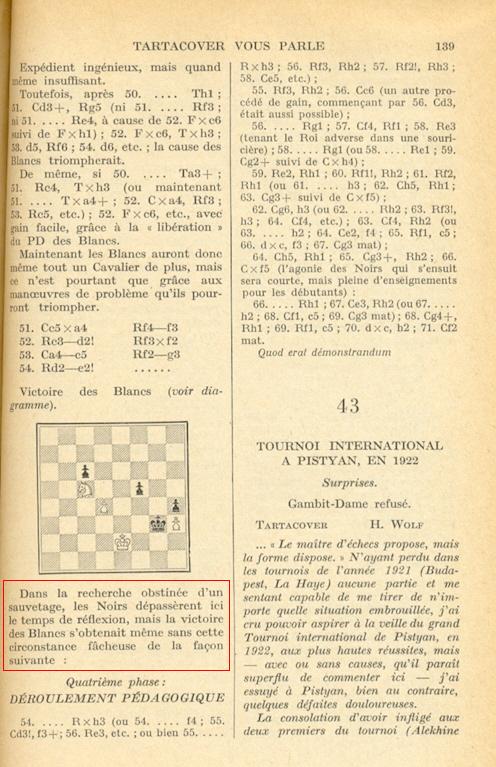

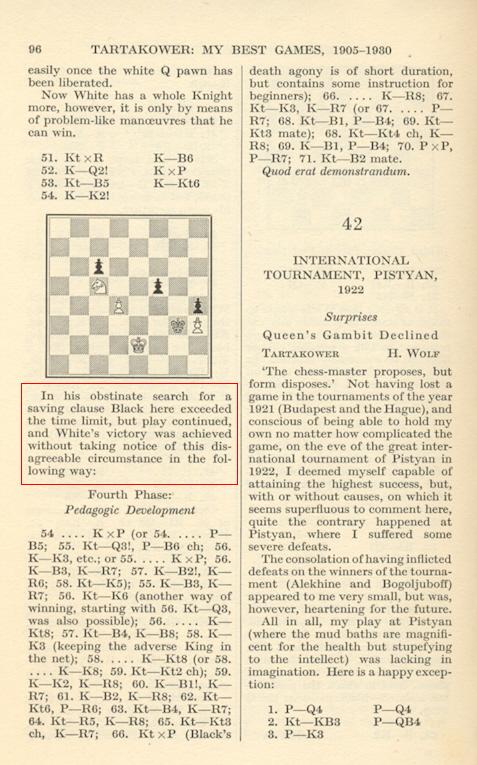

Tartakower is one of the most difficult chess writers to translate into English (among others are A. Nimzowitsch and F.K. Young), but on one relatively straightforward matter Golombek seems to have gone astray. It concerns the conclusion of Tartakower v Rubinstein, The Hague, 1921. The English edition (page 96) reads:

‘In his obstinate search for a saving clause Black here exceeded the time limit, but play continued, and White’s victory was achieved without taking notice of this disagreeable circumstance in the following way: ...’

The idea that play went on after Rubinstein’s flag had fallen is strange, and Tartacover vous parle (page 139) has something altogether different:

‘Dans la recherche obstinée d’un sauvetage, les Noirs dépassèrent ici le temps de réflexion, mais la victoire des Blancs s’obtenait même sans cette circonstance fâcheuse de la façon suivante: ...’

There is nothing about ‘play continued’ in the French version. A revised English translation would read:

‘In his obstinate search for a saving clause, Black here exceeded the time limit, but even without that disagreeable circumstance White would win, as follows: ...’

Golombek appears to have misunderstood ‘s’obtenait’ and to have set off down a wrong path which prompted him to add the words ‘play continued’.

However, one complication still needs to be considered. There exists a German translation, by Rudolf Teschner, of Tartakower’s book, under the title Tartakowers Glanzpartien, 1905-1930. Since it specifically billed itself as a translation from the French original, it would hardly be expected to follow the Golombek version rather than what appeared in Tartacover vous parle, yet it did exactly that:

We have found no contemporary (1921) source which suggests that the game continued to 71 Nf2 mate. On page 461 of the December 1921 BCM Sir George Thomas wrote after 53...Kg3, ‘At this stage, Black lost by over-stepping his time-limit. The game could not be saved in any case. A likely continuation would be 54 Ke2 ...’, after which he gave some 20 lines of analysis. See also page 25 of the tournament book by B. Kagan, page 215 of Schachjahrbuch 1921 by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1923), page 43 of 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1952), page 9 of the tournament book by A. Becker and page 19 of Akiba Rubinstein: The Later Years by J. Donaldson and N. Minev (Seattle, 1995).

(4437)

Christophe Bouton (Paris) reverts to the question of the second volume of Tartakower’s Best Games, of which an English translation by Harry Golombek was published by G. Bell in 1956. Given that no French edition has ever appeared, our correspondent asks if any information is available as to the whereabouts of Tartakower’s manuscript (e.g. in the archives of Golombek or of Bell).

The front cover of the original (1953) edition of Tartakower’s book on the period 1905-1930.

(4768)

Paul Morphy was described by Golombek as ‘perhaps the greatest chessplayer that ever lived’.

Source: page 51 of his book Modern Opening Chess Strategy (London, 1959).

(4620)

Regarding Chess by H. Golombek and H. Phillips (London, 1959), see our feature article on Hubert Phillips.

‘If this is Golombek’s English, we will eat our hat. It is more like the English of a well-educated foreigner.’

Harry Golombek, Schach-Express, 13 October 1949, page 11

(4970)

The remark quoted in C.N. 4970 (‘If this is Golombek’s English, we will eat our hat. It is more like the English of a well-educated foreigner.’) appeared on page 340 of CHESS, 15 July 1964 in a brief review of a book translated and edited by Golombek, Grandmaster of Chess The Early Games of Paul Keres (London, 1964).

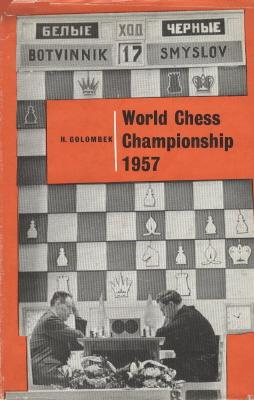

We recall too Wolfgang Heidenfeld’s review of World Chess Championship 1957 by H. Golombek (London, 1957) on pages 60-61 of the March 1958 BCM. Whilst praising aspects of the book, Heidenfeld quoted a passage describing the start of the third match-game, where ...

‘... the author uses over 40 words to say exactly nothing. One is almost surprised that he does not record the fact that both players were breathing (you know, by inhaling air). Could any of the stuff he sees fit to describe be of the slightest interest to any chessplayer anywhere in the world?’

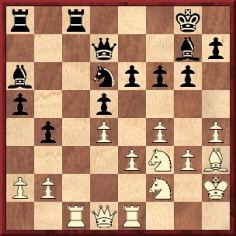

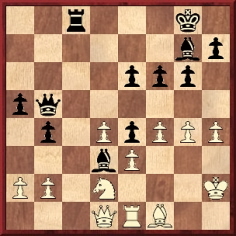

Heidenfeld stated that there was ‘far too much of this meaningless verbosity throughout the book’ and he also raised an analytical point that is worth noting. Having remarked that the analysis was sometimes ‘very good’, Heidenfeld added that the annotations were ‘quite often extremely superficial’. As an example he referred to page 104 (the 17th match-game):

White (Botvinnik) played 24 Rxc8+, and Golombek wrote:

‘In this phase of the game Botvinnik is scarcely recognizable. Now he meekly surrenders command of the QB-file without gaining the slightest compensation elsewhere. At least he should try for a K-side attack by 24 P-Kt4.’

Heidenfeld commented:

‘The annotator overlooks that the 24th move is virtually forced; that, in other words, Botvinnik is compelled to surrender the queen’s bishop’s file, meekly or otherwise, with or without compensation. For if he plays 24 P-Kt4 as recommended, there follows 24...RxR 25 QxR N-K5! – and with the queen deflected from Q3 and no piece able satisfactorily to protect the knight, White could hardly avoid 26 KtxKt PxKt 27 Kt-Q2 R-QB1 28 Q-Q1 B-Q6 29 B-B1 Q-Kt4, with a completely won position, which would not even offer White the chances he still obtained in the game.

It is absurd to imagine Golombek should not have seen this simple sequence of moves. Unfortunately, in this book, quite unlike his usual self, he seems to be too anxious to comment for the sake of commenting, which is precisely the attitude of mind that produces such superficialities.’

In a letter published on page 105 of the April 1958 BCM P.H. Clarke commented on the position after the 29th move in Heidenfeld’s line:

‘... unfortunately the South African master has not seen that after 29...Q-Kt4? ... White has a simple and obvious reply in 30 KtxP. Had he himself given the position more than a superficial study he might have noticed that 29...R-B7 (or even 29...Q-Q4) was the correct way to continue.’

On page 137 of the May 1958 BCM Heidenfeld acknowledged that he had been careless but stated that his error had not invalidated his criticism: ‘whether the line suggested ends in Q-Kt4? or R-B7! has no bearing on the fact that the original note in Golombek’s book – and unfortunately not this note alone – is carping and unnecessary criticism.’

We see that Smyslov’s own note to move 24 suggests that Rxc8+ was necessary and makes no mention of Golombek’s 24 g4:

‘White concedes the open file, since if 24 Bf1 there could have followed 24...Rxc1 25 Qxc1 Rc8.’

Source: page 296 of Smyslov’s Best Games Volume 1: 1935-1957 by V. Smyslov (Olomouc, 2003).

(4977)

This photograph was published on page 54 of the March-April 1940 American Chess Bulletin. The reference to Rueb is rather surprising.

(5168)

We are grateful to the Cleveland Public Library for this better-quality scan of the photograph:

From page 2 of Staunton Centenary Tournament 1951 by H. Golombek (published in London later that year):

(5202)

We have been re-reading Golombek’s chess column in The Times, which contained much of interest. On 10 December 1977 (page 11), for instance, he discussed, none too warmly, Fred Reinfeld’s writing career, although he seems to have considerably overestimated the quantity of the American’s production: ‘My own library contains 62 books by him and I believe this to have been about one fifth of his output.’ Reinfeld’s books on Botvinnik, Tarrasch and Nimzowitsch were deemed unimpressive, and regarding Nimzovitch the Hypermodern (Philadelphia, 1948) Golombek wrote:

‘... there appeared in the American Chess Review of the time a review couched in the most glowing terms that occupied the whole of the last page. No full signature appeared but simply the initials F.R., and your guess is as good as mine as to whether this meant that the review was by Fred Reinfeld.’

It is unclear what Golombek had in mind, but the extensive book review on page 184 of the June 1949 Chess Review was signed not ‘F.R.’ but ‘J.R.’ (John Rather, the magazine’s Managing Editor).

Although Golombek mentioned new chess literature relatively seldom, he usually practised plain speaking. Commenting in his column of 24 June 1978 (page 19) about Raymond Keene’s book on the 1977-78 Korchnoi v Spassky Candidates’ match, he wrote that the account ‘is so partial as to fail to carry any real conviction’. On 5 July 1975 (page 7) he observed:

‘... it is true that, like everybody else, I started off as a player and that when I won the London Boys’ Championship some 48 years ago I had not the faintest inkling that I would end up as that thing of silk, a mere chess journalist. ...

In the absence of such vates sacri as Breyer, Nimzowitsch, Réti and Tartakower we, who defend the bad against the worse, do our best to maintain a sort of semi-literacy in the world of chess. With certain shining exceptions our modern grandmasters lack the literary gifts of the four great players I have mentioned. All four were indeed genuine grandmasters both in playing chess and in writing about it.

Their books and writings will endure. I wonder how much of the flood of writing that we have nowadays will last.’

His columns naturally contain many reminiscences. On 29 October 1977 (page 11) he discussed F.J. Marshall:

‘I met him towards the end of his career when I was a young master and he was long past his most distinguished best. ... There was a genuine quality about him that, in combination with his enthusiasm and zest for chess, rendered him enormously sympathetic.

He was one of the few great players (Keres was perhaps the only other one) of whom no-one ever said anything to their detriment.’

Golombek was not always sure of his own playing record. On 8 November 1975 (page 11) he wrote:

‘I well remember the late Hugh Alexander asking me many years ago what were my results in my games against Sir George Thomas. I replied I was not sure but believed I was one or two up. Whereupon he laughed and said that was exactly the reply Sir George had given him when asked what his results were with Golombek.’

His column on 16 July 1977 (page 10) praised Alexander highly, noting that at Hastings, 1937-38 he had finished equal second with Keres, below Reshevsky but above Fine and Flohr:

‘Had events pursued their normal course I am now convinced that Alexander would have got very near the world title. The quality of his chess was rising all the time, and his knowledge of the technical part of the game continually deepening.

But then came the Second World War.’

On 2 July 1977 (page 9) Golombek referred to the 1935 Olympiad in Warsaw and his country’s match against Estonia:

‘I beat Ilmar Raud on fourth board, being rather surprised when, as I was about to give checkmate, my opponent took hold of my queen and made the mating move himself.

... To all those of us who took part in the Warsaw Olympiad and saw Keres play it was apparent that a new genius had arrived and one that was going to become a world force. ... I remember, since I was not playing in the 18th round, watching him beat Ståhlberg in the match Estonia-Sweden. After the game Ståhlberg was moving the pieces about the board in an attitude of disbelief and uncomprehension, and I asked him about the game. “He won”, said Ståhlberg. “He shouldn’t have done, but I don’t know quite why.”’

On 17 November 1973 (page 9) he related his experience at London, 1946:

‘This was an event comprising two international tournaments of approximately equal strength and remains vividly in my recollection as a period of intense cold when, owing to lack of heating, the temperature in the playing hall resembled that of Moscow on a dark winter night. I played in my overcoat and had big motoring gloves on so that when I had to make a move I lost some time taking a glove off.’

J. Stone and H. Golombek, from the London, 1946 tournament book

From the 20 August 1977 (page 9) column:

‘Looking back through the 50 odd years from the point when in my middle teens I first became aware there existed something like world championship chess right down to the present day, I would say that in my lifetime there have been five world champions who were and are great match-players as well as great tournament-players: These are, in chronological order, Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine, Botvinnik and Fischer.

Lasker and Capablanca were intuitively great match-players. They were blessed with the art of match-play in their bones at birth. But the other three, Alekhine, Botvinnik and Fischer, had to work hard to achieve the same heights as their intuitive predecessors. Not that this in any way reflects against them in their capacity both as great players and the creators of great masterpieces. A good book with a wonderful collection of games could be made out of a study of the match games of these three. Maybe I will attempt it if and when I finish the half a dozen books on which I am engaged at the moment.’

As regards that last remark, it seems to us that in the remainder of his life Golombek brought out only two books: his Encyclopedia and Beginning Chess.

He enjoyed making lists, and on 14 May 1977 (page 9) he gave an unusual selection of the ‘ten most interesting personages’ from the past 100 years:

‘I think they would be, in roughly chronological order, Zukertort, Charousek, Rubinstein, Nimzowitsch, Alekhine, Breyer, Tartakower, Bronstein, Tal and Larsen. Reserves could be Carlos Torre, Winawer, Pillsbury and Marshall and a half a dozen other American masters such as Dake, the proud friend of Al Capone, and William [sic] Weaver Adams, author of White to play and win and a sodium bicarbonate addict.’

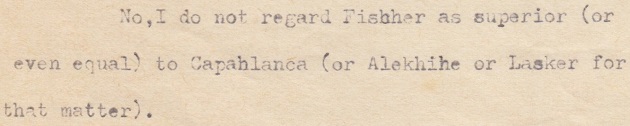

His column of 27 May 1978 (page 9) discussed Irving Chernev’s book The Golden Dozen (Oxford, 1976) concerning the 12 greatest players of all time. Noting that Morphy, Steinitz and Tarrasch were ‘strange omissions’, Golombek considered that the criteria should concern ‘not only prowess as a player but also what these great players have achieved and, most important, what contributions they have made to the knowledge and theory of chess’. Taking those factors into account, he offered as his top six, ‘in chronological order’, Morphy, Steinitz, Lasker, Capablanca, Alekhine and Botvinnik, and observed:

‘Perhaps (and here it is necessary in the interests of brevity to overdo the comparatives and superlatives) one might say that Morphy was the greatest player of the game, Steinitz the greatest innovator, Lasker the greatest practical player, Capablanca the greatest natural genius, Alekhine the most perfect player and Botvinnik at his best (and this best lasted quite a time), the most magnificent player the world has yet seen.’

Rather oddly, Golombek then added:

‘Nor am I by any means convinced that this is really and absolutely the top six. There are a dozen more, any one of whom could be among the leading six: Anderssen, Chigorin, Tarrasch, Rubinstein, Keres, Smyslov, Bronstein, Boleslavsky, Tal, Spassky, Fischer and Karpov.’

The idea of Boleslavsky being among the half-dozen greatest players of all time is certainly challenging.

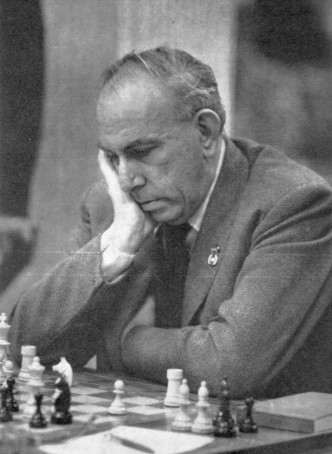

M. Botvinnik and H. Golombek, Alekhine Memorial, Moscow, 1956

Later in the same article Golombek wrote:

‘You will have noticed I have omitted Nimzowitsch from my lists, and this is because I have reserved him for a special list of the great eccentrics – to which list also belong such colourful figures as Breyer, Larsen and Simagin.’

Although Golombek was by no means averse to praising Nimzowitsch as a player and writer, his column on 17 September 1977 (page 10) expressed a less admiring view:

‘Colourful and energetic though his writings were, they are based on a fallacy. He gives you a collection of tactics which he elevates into a so-called system. His zestful writing and his great combinational gifts have tended to mask this; but in truth he gives us a façade rather than a building with inner dimensions.’

(5215)

From Harry Golombek’s column in The Times (Saturday Review), 29 October 1977, page 11, in a discussion of My Fifty Years of Chess by F.J. Marshall (New York, 1942):

‘I have been told he did not in fact write the book but that it was written for him. In any case one must assume that even if he did not actually write the work he told someone else what to write.

It is odd how this tradition of deputing other people to write one’s books seems to have flourished in America since Marshall was followed in this practice by two of the most outstanding of his successors as United States champion, Sammy Reshevsky and Bobby Fischer. It is also a little odd if indeed Marshall did descend to this practice since I gained the strong impression when I met him that he was one of the most honest and sincere of all grandmasters.’

Golombek’s further remarks about Marshall in that column were quoted in C.N. 5215 above.

(9834)

Chess has been called many things but, to our knowledge, only Harry Golombek has ever labelled it scribogenic. The neologism appeared in his column on page 10 of The Times of 1 October 1977:

(5357)

C.N. 3255 (see page 249 of Chess Facts and Fables) mentioned a reference to ‘Sir Henry’ Golombek on page 40 of The Sporting Scene by George Steiner (London, 1973). Below are some references to ‘Sir’ Harry Golombek in US sources:

Golombek, of course, was never knighted. He was merely given the OBE for services to chess, in 1966.

(5674)

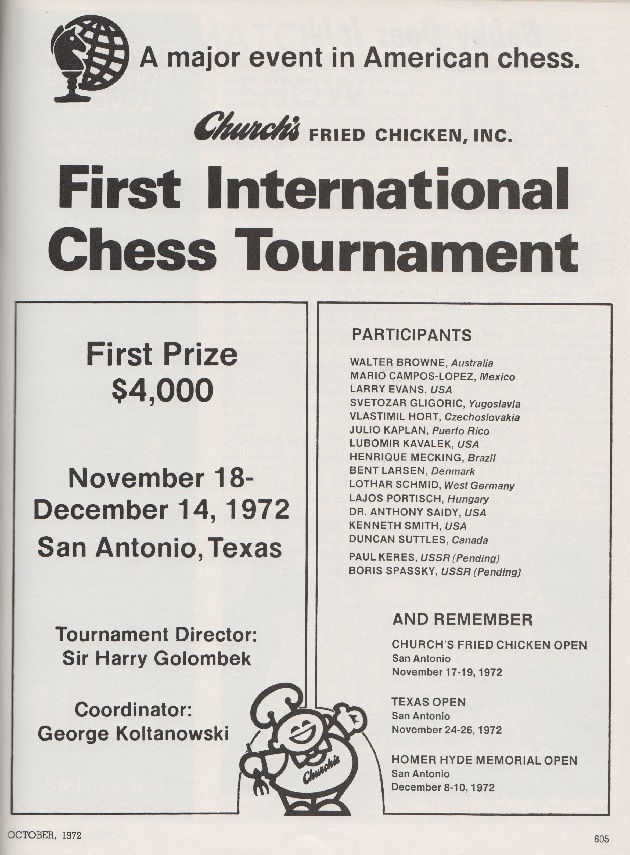

Dr Golombek’, ‘Sir Henry Golombek’ and ‘Sir Harry Golombek’ have been mentioned in C.N.s 3226, 3255 and 5674, and Geoff Chandler (Edinburgh) now adds a prominent specimen on page 605 of the October 1972 Chess Life & Review:

The announcement was repeated without correction on page 669 of the November 1972 Chess Life & Review. That latter issue (page 704) also had ‘Sir Harry Golombek’ in a feature about the San Antonio tournament.

‘Sir Harry Golombek’ is a mistake to be expected from Koltanowski; see, for instance, page 5 of Colle System (Coraopolis, 1984). Another example from the United States is the frontispiece of the book by Larry Evans and Ken Smith on the 1972 world championship match. That occurrence was criticized on the cover page iii of CHESS, June 1973, yet on the cover page iii of the previous month’s issue the magazine itself had referred to ‘Professor H.J.R. Murray’. For further instances of that error see The Chess Historian H.J.R. Murray.

(10855)

Maurice Carter (Fairborn, OH, USA) asks whether there is any truth to a story about Réti told by H. Golombek on pages iv-v of his Foreword to Réti’s Modern Ideas in Chess (London, 1943):

‘... There is related an anecdote typical of the man. In the closing stages of an international tournament he was playing one of the weaker competitors and had obtained a won game. It was his turn to move – an obvious one since all he had to do was to protect a threatened piece. He seemed to fall into a brown study, did not move for ten minutes; then suddenly started up from his chair – still without making his move – and sought out a friend who was present in the congress rooms. To him he explained that he had just conceived an original and entrancing idea for an endgame study. Not without difficulty his friend dissuaded Réti from demonstrating and elaborating this idea on his pocket chess set, and Réti returned, somewhat disgruntled, to the tournament room, made some hasty casual moves and soon lost the game.

Without troubling at all about this loss, Réti at once returned to his hotel and spent almost the whole of the night in working out his endgame study. As a consequence he lost his next game through sheer fatigue and with it went his chances of first prize. He perfected a beautiful endgame composition at considerable financial loss.’

(5905)

In C.N. 5905 a correspondent asked about Golombek’s claim that Réti lost two consecutive tournament games through being preoccupied by an idea for an endgame study which occurred to him during play.

Now, Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy) draws attention to a passage regarding the February 1928 tournament in Berlin in Jan Kalendovský’s monograph on Réti (see page 211 of the Czech original and page 374 of the Italian edition). It is stated that, after obtaining the better game against Brinckmann in round ten, Réti played 44 Nh5 but was informed that he had overstepped the time-limit. He then happily explained that the position on another board had inspired him to conceive a beautiful study. Still preoccupied with the study, he also lost his games against Tartakower and Steiner. His prize money was 500 Marks lower, but he produced the study, for which he received five Marks.

Corroboration of this account is sought.

(6016)

C.N. 2165 pointed out that on page 151 of Instructions to Young Chess-players by H. Golombek (London, 1958) Réti’s Modern Ideas in Chess was described as ‘the best book ever written on chess’.

Many entries in the 2004 volumes of the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography conclude with a reference to ‘wealth at death’. We note, in particular, the following:

(6418)

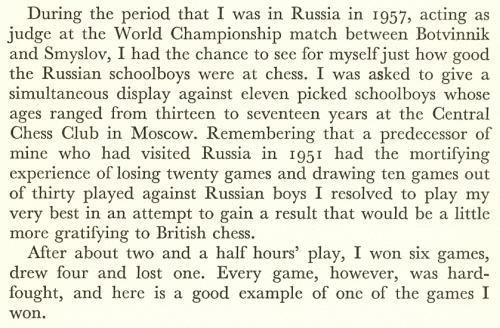

C.N. 2816 (see page 71 of Chess Facts and Fables) sought ‘lesser-known instances of masters making unfavourable scores in simultaneous displays’.

As regards a well-known case (+0 –20 =10 by R.G. Wade in Moscow, 1951), we should like to know whether the Soviet press of the time published any of the games.

H. Golombek referred to that display on pages 127-130 of Instructions to Young Chess-Players (London, 1958):

Harry Golombek – L. Barchatov

Simultaneous exhibition, Moscow, 1957

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 c4 Nf6 2 Nc3 e6 3 Nf3 d5 4 e3 Be7 5 Be2 O-O 6 O-O Nbd7 7 b3 b6 8 Bb2 Bb7 9 d4 c5 10 cxd5 exd5 11 Rc1 Rc8 12 dxc5 bxc5 13 Na4 Nb6 14 Bxf6 gxf6 15 Nb2 d4 16 exd4 Bxf3 17 Bxf3 cxd4 18 Qd2 Rxc1 19 Rxc1 f5 20 Rd1 Bf6 21 Qf4 Qd7 22 Nd3 Rc8 23 Qh6 Qd6 24 g3 Rc2 25 Re1 Be7 26 Qh5 Rxa2 27 Qxf5 Qf6 28 Qg4+ Kh8 29 Nf4 Qg5

30 Qh3 Rb2 31 Be4 h6 32 Ra1 a5 33 Rxa5 Qf6 34 Rf5 Qg7 35 Nh5 Qg6 36 Re5 Qd6 37 Qf5 Resigns.

(6451)

C.N. 1809 quoted from page 218 of Beginning Chess by Harry Golombek (Harmondsworth, 1981):

‘It is one of the many delights of chess that it is a literate game for literate people, and this means that a good book on chess is almost inevitably a pleasure to read. Here, therefore, follows a list of further reading which I think you will find both enjoyable and profitable.’

We commented:

The list features 14 titles. Golombek wrote four of them, translated three, co-authored one and wrote the foreword to one. The remaining five managed to be good without him.

Here, a new matter is raised. On pages 61-62 of Beginning Chess Golombek recalled that at the British Championship in Harrogate in 1947 he won his last-round game against B.H. Wood and was then leading the tournament by half a point, ahead of R.J. Broadbent.

‘I stayed to watch his game against R.H. Newman; if he won this game, then he won the championship; if he drew then we were level and would have to play off a match for the title; and if he lost, then I won the championship.

The game grew very exciting and suddenly I noticed that Newman could promote a pawn to a knight, giving check and forcing a win. He did promote the pawn – but to a queen; and after many complications the game was drawn. Afterwards I asked him why he hadn’t made a knight instead of a queen: “Never thought of it”, was the reply. Well, if you have a similar situation, no doubt you will think of it.’

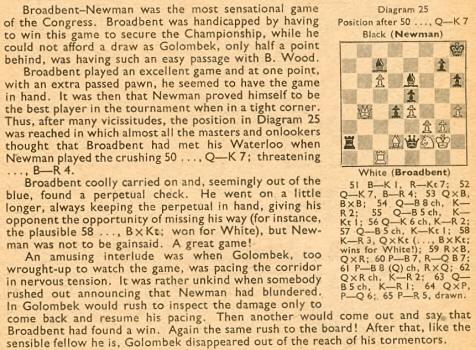

Only the conclusion of the game was given in the BCM (September 1947, page 293):

Despite the description ‘the most sensational game of the Congress’, we have yet to find the complete game-score.

(6484)

Harry Golombek’s Modern Opening Chess Strategy (London, 1959) was dedicated to Sidney Weiland of Reuters (‘but for whom the following pages might never have been written’), and the Acknowledgements page thanked Reuters ‘for their kind permission to reproduce much of the material in this book’.

Information on Golombek’s connection with Reuters at that time would be welcome, and particularly since the book comprised detailed openings analysis and not news or reportage.

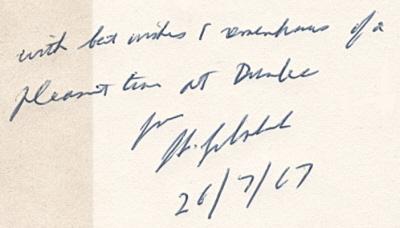

Below is an inscription by Golombek (Dundee, 1967) in one of our copies of Modern Opening Chess Strategy:

As regards his (later) work as a correspondent for the news agency, the following appeared in the announcement of his book on the 1972 world championship match in the February 1973 CHESS:

‘Golombek was at Reykjavik reporting for The Times and Reuter throughout the play.’

(6510)

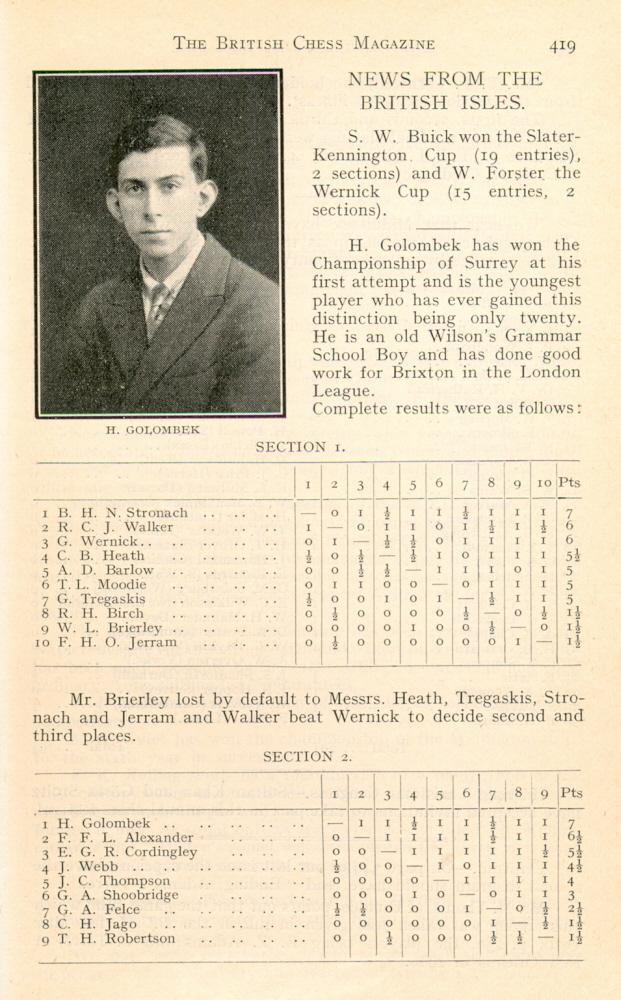

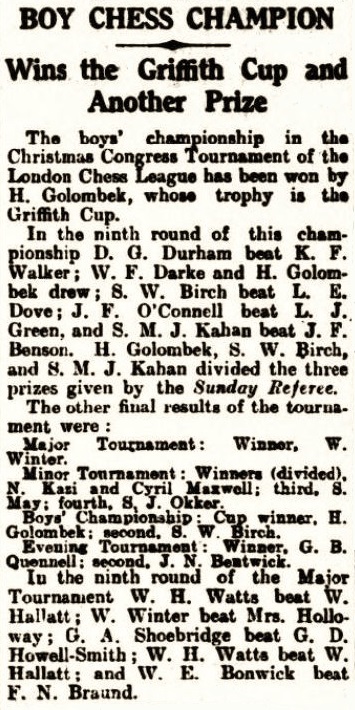

Page 419 of the September 1931 BCM:

(6555)

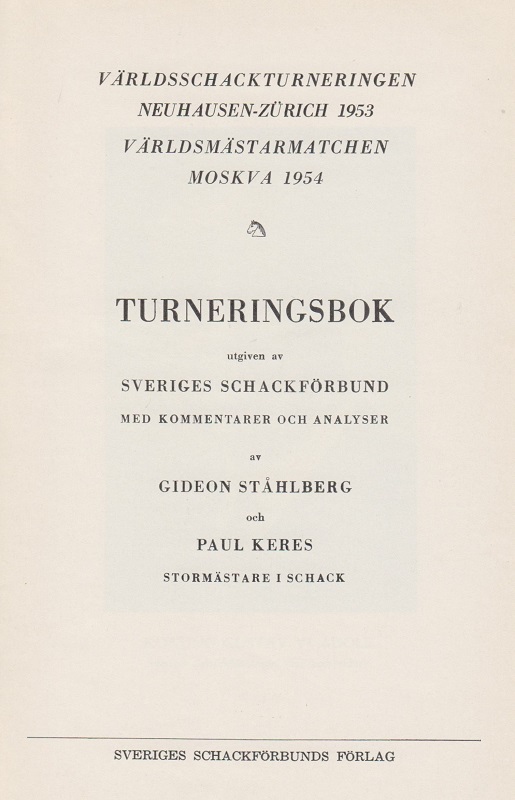

‘Nobody amongst living players has such an elegance of style as Ståhlberg when playing at his best.’

Harry Golombek expressed that view on page 124 of a book which he translated and edited: Ståhlberg’s Chess and Chessmasters (London, 1955). He also praised the Swedish master’s style in his obituary on pages 230-231 of the August 1967 BCM:

‘... It is apparent that he was one of the most active and successful tournament players of our time and certainly the most successful Swedish player of all time. But more important is the style in which he played and achieved these results. Style is the operative word in his case; elegant, cultivated, correct, and always with an additional spice of imagination and originality, his was a style that was at once pleasing and effective.’

(6947)

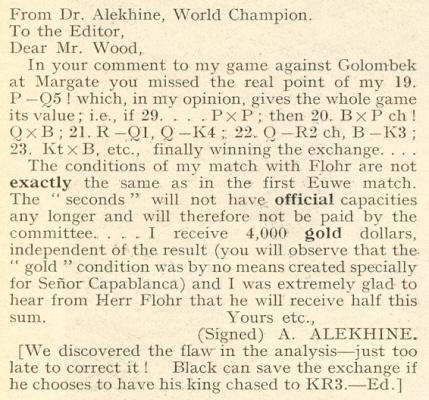

From page 376 of the 14 July 1938 issue of CHESS:

The position in the Alekhine v Golombek game (before 19 d5) had been given on page 360 of the 14 June 1938 CHESS, with this note:

‘Black might well have tried capturing the pawn, e.g. 19...PxP 20 R-Q1 Kt-K2 21 P-K4?! P-KR3 with some freedom.’

On the same page CHESS indicated the time taken on the game: one hour by White and two hours by Black.

Alekhine’s remark on the projected match with Flohr was in response to this paragraph on page 337 of the 14 June 1938 CHESS:

‘Dr Alekhine and Flohr have signed a contract for a world’s championship match in the autumn (fall) of 1939. The match will be played at various places in Czechoslovakia and the financial and other conditions are to be exactly the same as for the Alekhine-Euwe matches.’

(7061)

Daniel Naroditsky (Foster City, CA, USA) offers some examples of errors in Chess School 2 The Manual of Chess Combinations by Sergey Ivashchenko (Moscow, 2002), including the following:

Page 151 (position 840): Foltys v Golombek, ‘Prague, 1947’:

‘The game was played not in Prague but in London (in a match between Great Britain and Czechoslovakia). According to the book, the solution is 1 Rxa6 Rxa6 2 Rb7 Rg7 3 c7 Ra8 4 Rb8 Rg8 5 Rxa8 Rxa8 6 Nd7+ Ke7 7 Nb8. But, of course, 7…Ra1+ followed by 8…Rc1 wins outright. The explanation is that a white pawn is missing in the diagram position. In the actual game Black resigned after the rook capture on a8.’

(7087)

A late specimen of Harry Golombek’s play was given in his column in The Times on 17 January 1981, page 10. Despite supplying a detailed description of the computer against which he had been pitted ‘recently’, he merely named it in the game heading as ‘Machine’.

Harry Golombek – ‘Machine’1 c4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qb3 Nc6 5 a3 Bxc3 6 Qxc3 d6 7 b4 Bd7 8 Bb2 O-O 9 e4 e5 10 d4 exd4 11 Nxd4 Re8 12 f3 Nxd4 13 Qxd4 Qe7 14 Be2 a6 15 O-O Rad8 16 Rac1 Qe5 17 Qxe5 dxe5 18 Rfd1 Re6 19 Bf1 c6 20 Rd2 Rde8 21 Rcd1 R6e7

22 a4 Rd8 23 b5 c5 24 Rd6 axb5 25 cxb5 Ra8 26 Ba3 Rxa4 27 Bxc5 Be6 28 Rd8+ Re8 29 Rxe8+ Nxe8 30 Rd8 g6 and White won.

After Black’s 30th move Golombek commented:

‘Here it looked at first R-R7, then B-Q2, P-R3 and P-B4 and then back to P-R3 and P-KN3. It spent 29 minutes 44 seconds on this hopeless procedure and staggered on for another ten moves before I mated it.’

(7142)

‘... even when drunk he [Alekhine] could see a great deal further over the board than most chessplayers sober. I remember that, at the Warsaw International Team Tournament of 1935, I was showing a game I had won that day to the fellow members of my team. Alekhine came up, recognized the game and complimented me on it in mellow, if somewhat thickly intoxicated, tones and, in a flash, indicated a vital, winning variation we all had missed.’

Source: ‘Recollections of Alekhine’ by Harry Golombek, Chess Review, May 1951, pages 140-141. See too C.N. 1313. Golombek’s article can also be found on pages 191-196 of The Treasury of Chess Lore by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1951).

The relevant game from the 1935 Olympiad was not identified, but one possibility is Golombek v Horowitz. The former’s annotations on pages 480-481 of the October 1935 BCM referred to 24 h4 as a possible improvement suggested by Alekhine; at moves 28 and 33, shorter wins were pointed out by Golombek (without, however, any mention Alekhine).

(7205)

The frontispiece of the booklet Southsea Chess Tournament 1949 by H. Golombek (Birmingham, 1949):

From an article by G.H. Diggle published in the September 1980 Newsflash and reproduced on page 61 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984), concerning the 1980 British Championship in Brighton:

‘The Tournament Officials and Wise Men were as enthralling to watch as the players, being ensconced on a distant sort of Mount Olympus to which “nymphs” ascended from time to time with cups of coffee, and from which one patriarch would occasionally come down, and with a countenance heavy with affairs of state vanish through a secret door. The Press, also, “had their exits and their entrances”. Most impressive of all was that of the renowned doyen and “man of a million Congresses”, “H.G.”. Arriving becomingly late, he proceeded in unhurried swan-like manner right up the hall, bowed gracefully to a passing acquaintance, glided (“such being his prerogative”) into the forbidden area behind the ropes, stood for some moments in a reverie, looking neither to the right nor left, and finally sailed away westwards, the epitome of vast experience and sunset calm.’

(8048)

From pages 166-167 of Beginning Chess by Harry Golombek (Harmondsworth, 1981):

‘This is a variation from a game, Golombek-H.E. Price, Hastings, 1932-33, for which White was awarded a brilliancy prize. White now plays 1 NxB, and after 1...QxQ 2 BxP mate. The perfect co-operation between bishop and knight has enabled White to dispense entirely with his queen.’

The event was the Premier Reserves tournament, but we have yet to find the game-score.

(8207)

1 c4 Nf6 2 d4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 e4 d6

5 f3 O-O 6 Be3 Nc6 7 Qd2 Re8 8 Nge2 Rb8 9 O-O-O a6 10 h4 h5 11

Bg5 b5 12 g4 hxg4

13 Bg2 Na5 14 cxb5 Nc4 15 Qf4 Nh5 16 Qh2 axb5 17 Ng3 c5 18 Nxh5

gxh5 19 fxg4 Qa5 20 Kb1 b4 21 Nd5 Ra8 22 White resigns.

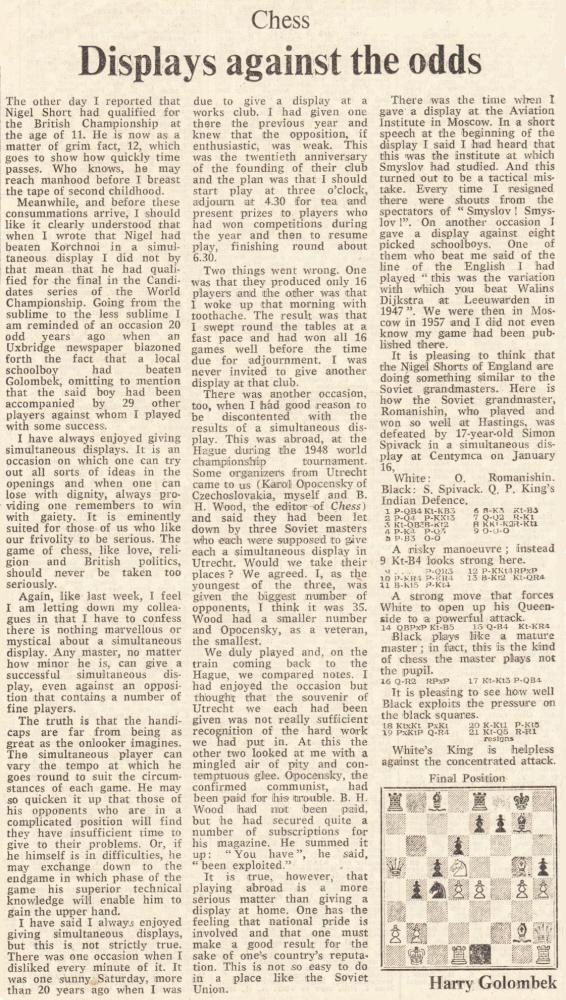

Golombek’s column was published on page 11 of the 11 June 1977 Review section of The Times. Concerning the simultaneous display by Romanishin, further details and games were given in ‘Young London v the IGMs’ by Leonard Barden on pages 270-272 of the June 1977 BCM.

(8262)

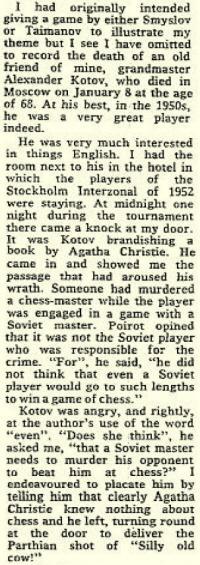

Alexander Kotov’s assessment of Agatha Christie was reported by Harry Golombek in The Times Saturday Review, 25 April 1981, page 9:

(8272)

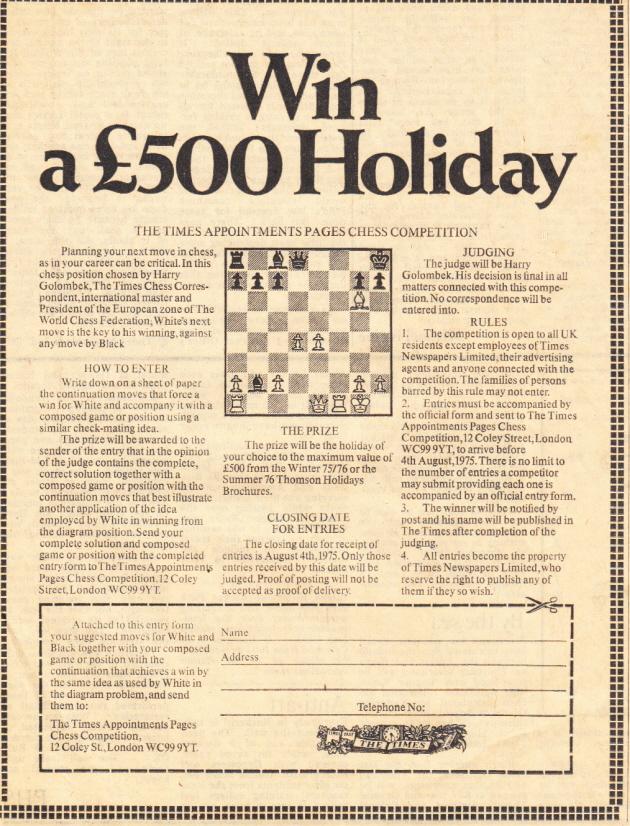

This feature was published in The Times on page 9 of the 6 June 1975 edition, and on many occasions subsequently. The competition diagram also appeared on posters at, for instance, London underground stations. The winner, P.F. Copping, was announced on page 4 of The Times, 7 February 1976, and the contest was discussed on pages 302-303 of the February 1976 issue of EG.

Harry Golombek wrote a lengthy article, ‘A Successful Experiment’, on pages 168-171 of the April 1976 BCM, and on page 170 he reported:

‘The set position was the finish of a game played at Smolensk in 1950 between Jesierski (White) and Lelczuk.’

In a database we note a game (1 e4 e5 2 f4 Nc6 3 Nf3 d6 4 fxe5 Nxe5 5 d4 Ng6 6 Bc4 Be7 7 O-O Nf6 8 Nc3 O-O 9 Qe1 Re8 10 Ng5 d5 11 Nxd5 Nxd5 12 Bxd5 Bxg5 13 Bxf7+ Kh8 14 Bxe8 Bxc1 15 Bxg6 Bxb2 16 Qh4 Qxh4 17 Rf8 mate) which is labelled Jezierski v Lelczuk, Smolensk, 1953. On pages 85-86 of Test Your Chess IQ: Book 2 by A. Livshitz (Oxford, 1981) the position appeared as Ezersky v Lelchuk, Smolensk, 1950.

(8310)

For further information about the game, see C.N. 8314.

A photograph on page 303 of A Chess Omnibus:

From B.H. Wood’s column in the Illustrated London News, 30 March 1963, page 482:

‘I know of only one book devoted to the saving of lost positions; that is, not unexpectedly, by Fred Reinfeld, who must in the course of his lifetime have racked his brain to think what he could write about next. (His enormous output once prompted David Bronstein to remark that, whilst — — [Wood’s dashes] might possibly be the best writer of chess books in the English language, Fred Reinfeld was obviously the best lightning-chess-writer.) Illuminatingly, this book is one of Reinfeld’s very latest, showing clearly that it is one of the last subjects that even occurred to such a prolific writer.’

And from Wood’s column on page 114 of the 28 May 1977 issue:

‘It was Flohr, I think, who compared him [Golombek] with Reinfeld, who also wrote a great many chess books, describing Reinfeld as the world’s worst lightning chess writer, Golombek as the best (lightning chess is the term for chess played at an average of a few seconds per move). The assessment is hard on Reinfeld; Bob Wade has remarked again and again how poorer players find him helpful. It is kind to Golombek, whose books sometimes exhibit a smooth sameness, who had one rather egocentric period and who can find it difficult (who does not?) to avoid repeating himself.’

Is anything further known about the views attributed to Bronstein and Flohr?

(8364)

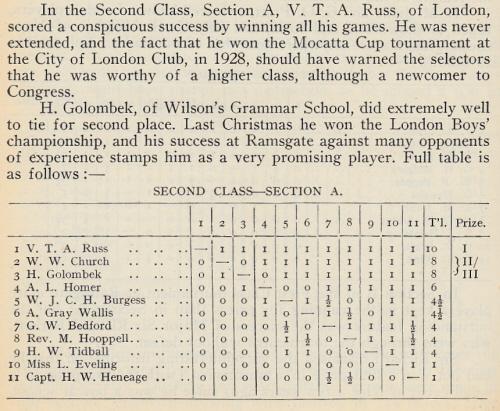

From page 342 of the September 1929 BCM, in a report on that year’s British Chess Federation Congress in Ramsgate:

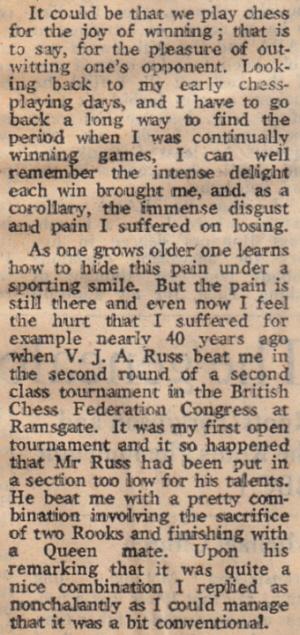

Page 270 of the June 1928 Chess Amateur reported that the Mocatta Cup had been won by ‘V.J.A. Russ’, which was also the name used by Golombek on page 10 of The Times, 9 April 1977 when discussing the pain of losing in Ramsgate:

Golombek (whose reference to ‘nearly 40 years ago’ is a typo or miscalculation) also mentioned ‘Russ’s quiet, almost timid, satisfaction with the beauty of his combination’. Can the game-score be found?

(8534)

Chess literature seems to offer almost no information about the London, 1937 tournament mentioned in C.N. 8736. Below is a reference to it by Harry Golombek in his Times column, Review section, 29 September 1973, page 11:

(8741)

On page 38 of The Best Games of C.H.O’D. Alexander by Harry Golombek and Bill Hartston (Oxford, 1976) Golombek wrote regarding Warsaw, 1935:

‘This Olympiad stands out in my memory as the most exhausting event in which I ever played. The schedule was a crowded one in which, on a number of days, we had to play two rounds in one day.’

...

In a report on the Stockholm event on pages 16-17 of CHESS, 14 September 1937 Harry Golombek wrote:

‘The pace is cracking: three games every two days; adjournments galore.’

A further observation by Golombek:

‘Striking, too, is the different attitude adopted by the chessplayer according to his nationality; his temperament or the position of his game. Flohr, for instance, has a care-worn expression whatever his position. Ståhlberg always seems overwhelmed by a calm melancholy. The Americans wear a peaceful, assured expression; here the consciousness of power is very evident. They, and everybody else, realize the US have sent to Stockholm the strongest team that has ever played in an international team tourney.’

He also discussed the playing conditions in Stockholm:

‘What strikes an habitué of London, Hastings or Margate most of all is the prevailing hum of by no means light conversation. Silence is not strictly enforced by any means. The sound is a strange polyglot blend composed of about 18 languages. Through the mixture there runs a prevailing strand of Swedish underlying which is a subordinate texture of German (for German is the lingua franca of the international chessplayer). Noise does not seem to disturb the players, most of whom could apparently play on unaffected in an aerodrome with 50 aero-engines going all out ...

... The spectators walk round the sides of the room which have naturally been carpeted to prevent noise. The number of these spectators has been very large, for chess is very popular in Sweden; over 10,000 paid to come in during the first week.’

(8756)

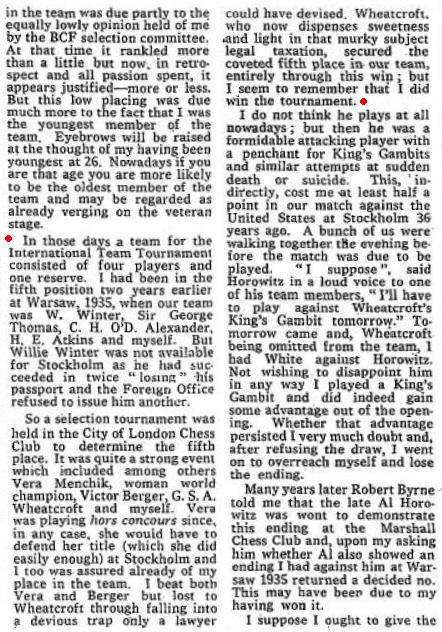

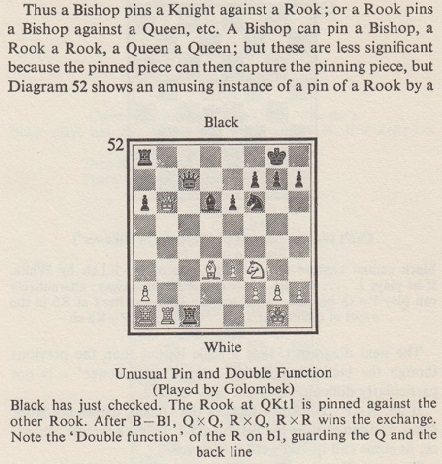

From page 215 of Technique in Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1961):

The passage was referred to in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column on page 303 of the October 1965 BCM:

There was also a brief reference on page 359 of the December 1965 BCM.

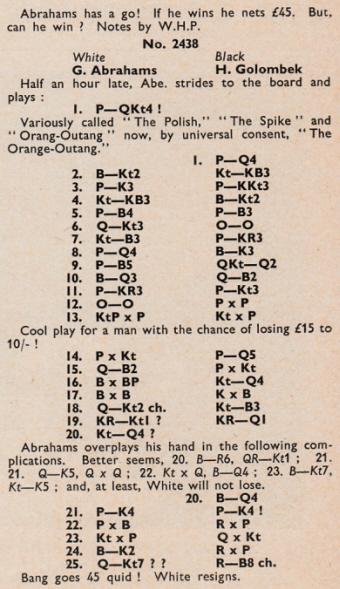

Below is the finish as given on page 57 of the BCM, February 1948:

The game was ‘annotated’ by W.H. Pratten on page 121 of the February 1948 CHESS:

Although sometimes dated 1947, the game was played on 6 January 1948, as reported on page 7 of the Times the following day.

(8842)

As shown in C.N. 8842, this was the final position in Abrahams v Golombek, Hastings, 1948:

On page 67 of The Handbook of Chess (London, 1965) Abrahams gave a different position and named only Golombek:

(8913)

From the inside front cover of CHESS, 18 October 1958 we quote the opening sentence of a brief notice of Instructions To Young Chess-Players by H. Golombek (London, 1958):

‘A book with no special features, except that in his bibliography the author recommends fewer of his own books than usual.’

(8872)

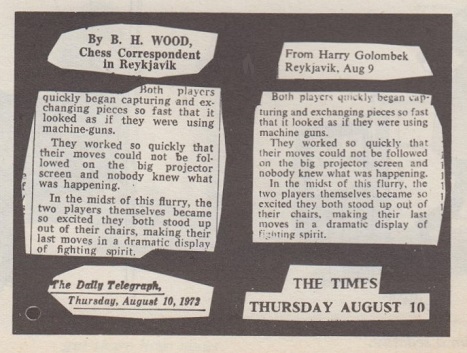

A curious item from page 204 of the 16-22 August 1972 issue of Punch:

Can any reader take the matter further?

Harry Golombek was mentioned in a spoof on page 67 of Punch, 14-20 January 1970:

(9106)

On the subject of hypnotism (Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) adds the case of Romark, who was discussed by Harry Golombek on pages 95-96 of Fischer v Spassky (London, 1973). Golombek quoted the following ‘from what I wrote at the time’:

‘Romark, Newcastle’s own Ron Markham, has challenged Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky to play a consultation game against him at the end of the match and this for a stake of £125,000. Fischer and Spassky are asked to put up £62,500 each as their stake. So confident is Romark of winning that he is putting up £25,000 himself, the remainder being provided by his backers and associates. More, he is prepared to play blindfold against them.

... The reader, if as ill-informed as I was, might now ask who is Romark, what is he? Here are some facts provided by his publicity agents. At present he is based in Durban. At an anti-smoking rally in Newcastle last year he cured 2,000 people of smoking. This year, in Durban, before an audience of doctors, he hung [sic] himself for four minutes, was officially pronounced dead, and then, presumably, recovered. Romark says he is an average chessplayer. He would appear to be a more than average hypnotic medium.’

Golombek’s original article, ‘High drama in Reykjavik’, was written in Iceland during the world championship match and appeared on page 11 of The Times, 19 August 1972. Before coming on to Romark, Golombek indulged in much booksy waffle, contriving to mention Corneille, Agatha Christie and The Mousetrap, Brian Rix’s farces, Racine, Mozart, The Caretaker and Lord of the Flies. He also gave Spassky’s win in the 11th match-game, with brief notes.

A small advertisement on page 23 of The Times, 27 June 1975:

(9129)

From page 140 of the May 1951 Chess Review, in an article entitled ‘Recollections of Alekhine’ by Harry Golombek:

‘Witness, too, his writings on the game, which must rank with the best that the chess world has produced. The number of young players whose imagination has been stirred and for whom fresh vistas have been opened by his My Best Games of Chess 1908-1923 must be legion.

It is true, however, that in writing this book and others, he owed much to other masters and was not always frank in acknowledging the debt. In his collections of games, for example, he owed a great deal to the French masters, Renaud and Kahn.’

Did either Renaud or Kahn ever write about the matter? And did Golombek give more details, e.g. to justify his words ‘this book and others’ and ‘for example’?

(9161)

On page 29 of Chess World, February 1960 C.J.S. Purdy wrote:

‘If – we almost wrote “when” – Botvinnik loses the current match, he will have the right to a return match in 1961 ...

Tal seems generally favoured to beat Botvinnik. We think stamina will decide in Tal’s favour ...’

And from page 73 of the May 1960 issue:

‘This was the only world title match about which we have ever ventured a prophecy.’

On page 57 of the April 1960 Chess World Purdy criticized Harry Golombek, under the heading ‘Extraordinary Prediction’:

‘At that stage [after the short draw in the 13th match-game], with Tal two games ahead, Golombek published an extraordinary prediction that Botvinnik would hold his title. Golombek faces the alternative prospect of becoming known as either the greatest prophet or the greatest neck-out-sticker in chess history.

... One of the reasons that Golombek gives is that Botvinnik has a better knowledge than Tal of the openings that are being played! Here is logic to make poor old John Hanks writhe in agony. It would be just as sound to say one tennis player should beat another because his service is superior.

... Golombek’s writings all tend to show that he regards chess rather too much as a body of knowledge. If knowledge of the openings went far, Golombek himself would be one of the world’s best players.

Chess is primarily a skill. It’s mainly a matter of who sees the mostest the fastest. Tal sees the mostest the fastest of all. He would have done better still had he played more soberly after amassing a three-point lead.

Seeing the mostest the fastest is not the whole story. Petrosian may be Tal’s equal there. That is technique. After that comes the art of choosing between moves that technique ranks equal, or as possibly equal. Petrosian, like Capablanca, will always choose the calculable. Tal will often choose the incalculable. Such a player develops an intuition for chances. Tal’s intuition is not perfect, as we see from the ninth game, below, but many of his other games show that it is almost magical, all the same.

Golombek’s prediction may possibly come true, but the reasoning he bases it on is faulty. He seems to be a Botvinnik fanatic.’

It is unclear to us which particular text or texts by Golombek prompted Purdy’s remarks. Our reading of the game-by-game reports by Golombek from Moscow in the BCM and The Times is that he was even-handed and not remotely a ‘Botvinnik fanatic’.

Chess Review, May 1960, page 136

(9835)

Jacob Bronowski and Chess refers to Harry Golombek’s self-centred ‘tribute articles’ on page 13 of The Times, 5 October 1974 and pages 441-443 of the December 1974 BCM. An episode related in both publications dates from the late 1920s:

‘... on holiday at a seaside resort on the southern coast I had a number of conversations with a worried looking gentleman in my boarding house while the rain was falling. This was Bronowski’s father, and the reason why he was worried was that he was full of forebodings about his son’s tendency to dissipate his undoubted gifts on what seemed to him mere side-issues. He was writing poetry and, as for chess, he was giving too much time to chess problems. “A waste of time”, I commented in the full certainty of my 17 years. “Yes”, said Bronowski père, “that’s what I’m always telling him.”’ (Times)

‘... he asked for my advice about his son. He was at Cambridge University and, according to the father, dissipating his undoubted talents in all sorts of unrewarding side-issues. He was even writing poetry and as for chess, he had recently taken up problem composing instead of the more solid pursuit of actually playing chess. What, he asked, did I think of chess problems. “A waste of time”, I replied. Before there are howls of protest, let me add that I have learnt better now. I consider problems just as much, or as little, waste of time as playing chess, going in for politics or religion, practising the law or train-spotting, negotiating to enter or leave the EEC or just simply, like Candide, cultivating one’s garden. Anyway, my reply appealed to Bronowski père, who said, “That’s what I’m always telling him.”’ (BCM)

Golombek’s writings throughout his life showed little interest in chess compositions.

(9993)

From C.N. 177:

In 1974 the BCM was the victim of a cruel hoax when it published what purported to be an obituary of Dr Jacob Bronowski (pages 441-443). The writer, not the first name that would come to mind in the humility stakes, decided to abandon the tiresome conventions of obituaries and write about himself. There can never have been an obituary where the personal pronoun ‘I’ was used more often or with more insensitivity. It is a desperate shame that Harry Golombek, who gained an OBE for his services to chess (and, believe it or not, he even dragged that fact into poor Dr Bronowski’s death-notice), should be afflicted with two self-promoting vices: egocentricity and logorrhoea.

...

P.S. Milner-Barry wrote about his and Alexander’s code-breaking work on pages 3-5 of Golombek and Hartston’s The Best Games of C.H.O’D. Alexander (Oxford, 1976) and included the following tantalizing comment:

‘Much has been written lately about what came out of Bletchley, but only from the point of view of the user. Security restrictions on the story of the breaking of the Enigma from the technical point of view have not yet been lifted. I still hope that they may be in my time. It would, I believe, make an enthralling story which would be particularly fascinating to chessplayers. For both Hugh and myself it was rather like playing a tournament game (sometimes several games) every day for five and a half years.’

Milner-Barry lived until 1995. Dare it be hoped that he wrote up his recollections of the 1940s?

Harry Golombek, who died the same year as Milner-Barry, was also at Bletchley Park. In his obituary of Jacob Bronowski on pages 441-443 of the December 1974 BCM he recalled being heartily recommended to an Intelligence Department of the Foreign Office by his artillery commanding officer on the grounds that ‘I had too much brains to be behind the guns’. On page 131 of his Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977) Golombek stated that he was at Bletchley Park ‘like Alexander, Milner-Barry and quite a number of other chessplayers’. Who were the others?

We note, finally, the following on page 162 of Simon Singh’s The Code Book (London, 1999):

‘Initially, Bletchley Park had a staff of only two hundred, but within five years the mansion and the huts would house seven thousand men and women.’

(4029)

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) writes:

‘See CHESS, February 1945, page 73, for a report of a 12-board match on 2 December 1944 between Oxford University Chess Club and Bletchley Chess Club. The Bletchley team (which won 8-4) included C.H.O’D. Alexander and H. Golombek on boards 1 and 2. Board 3 featured J.M. Aitken, board 4 was I.J. Good, and board 5 was occupied by N.A. Perkins. Full team details were given, as well as a photograph of the players:

An article based on this information was published on pages 10-11 of Scottish Chess, June 2005.’

Milner-Barry was not mentioned in the CHESS report. As regards his surviving papers, Leonard Barden (London) draws our attention to their location. [Replacement link.]

(4034)

See also Chess and the Code-Breakers.

Harry Golombek was in characteristic form in his Times column, Review section, page 9, 6 May 1972:

The work referred to by Golombek was undertaken in the early 1950s. On pages 278-279 of the October 1952 BCM he wrote:

‘For some years now the FIDE has been making attempts to revise the old rules and produce a new version that will avoid the ambiguities, omissions and falsities that abounded in the former set of rules of chess. The matter proved too complex to be dealt with at last year’s congress at Venice, when the sub-committee for the task produced differing drafts exceeding in number the actual composition of the committee.

This time a sub-committee was appointed to consider a new version (members being the President of FIDE, Folke Rogard, and Messrs Berman, Golombek and Wade). After some arduous and concentrated work this committee was able to agree on a final version that was subsequently approved by the General Assembly ...’

The text was finally passed by FIDE’s Congress in Schaffhausen the following year. Source: page 273 of the British Chess Federation’s Year Book 1953-1954 (Leeds, 1953). Pages 273-293 gave the full text.

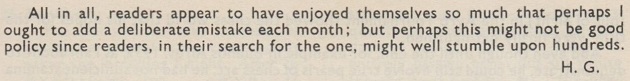

Further to C.N. 10198, below is an extract from the section regarding castling, on page 277:

‘Castling is a move of the king and a rook, reckoned as a single move (of the king), which must be carried out in the following manner: The king is transferred from its original square to either one of the nearest squares of the same colour in the same rank; then that rook towards which the king has been moved is transferred over the king to the square which the king has just crossed.’

Page 279 stated that ‘a move is completed ...’

‘... In the case of castling, when the player’s hand has quitted the rook on the square crossed by the king; when the player’s hand has quitted the king the move is still not yet completed, but the player no longer has the right to make any other move except castling.’

(10218)

On the subject of Harry Golombek and FIDE meetings, we recall the concluding paragraph of his report on the FIDE Congress in Sofia (September 1961) on pages 48-51 of the British Chess Federation’s Year Book 1961-1962 (Warrington, 1961):

A brief Internet search shows an entity which produces noodles. The Bulgarian products include this one:

(10219)

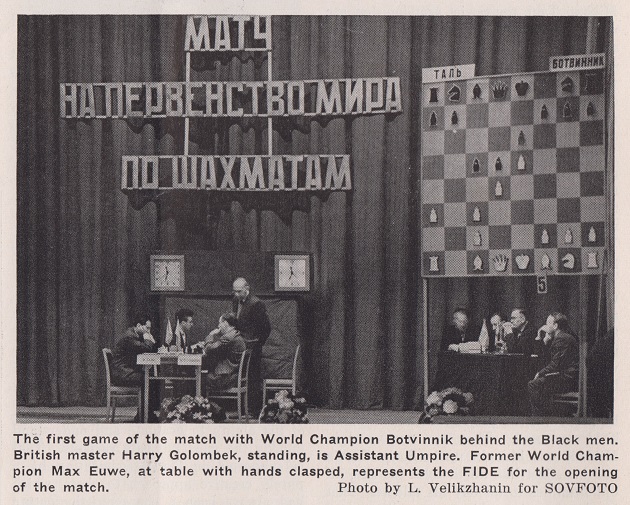

A photograph taken during the Candidates’ tournament in Yugoslavia, 1959:

From left to right: Petrosian, Golombek (chief arbiter), Tal, Gligorić, Smyslov, Benko, Fischer, Ólafsson, Keres.

Source: Chess Review, December 1959, page 360. A less clear copy of the picture is opposite the imprint page of Kandidatenturnier für Schachweltmeisterschaft by S. Gligorić and V. Ragozin (Belgrade, 1960) with the caption ‘Alle Spieler mit grossen Hoffnungen: Vor dem Turnierbeginn in Bled’.

(10332)

From the dust-jacket of Chess: Games to Remember by I.A. Horowitz (London, 1973):

No such book is on record, although in 1981 Penguin Books brought out Beginning Chess by Harry Golombek.

A snippet from the Introduction (page 7):

‘I have known one real mathematical genius in my life and he, while passionately fond of chess, played it atrociously. I could give him the odds of a queen (the most powerful piece in the game) and still beat him.’

The penultimate paragraph on the same page:

‘Chess does indeed have some therapeutic value in the matter of training the mind; it helps to concentrate the mind wonderfully. But so, according to Dr Johnson, does the prospect of being hanged next day [sic].’

(10602)

‘“To the world champion of Chess Literature” – such was the flattering manner in which Smyslov inscribed the book of his collected games which he presented to Harry Golombek on the day he won the world championship from Botvinnik.’

Source: page 170 of The Delights of Chess by Assiac (London, 1960). For a more specific, and less flattering, assessment, see Harry Golombek’s Book on Capablanca.

(10636)

From the ‘Foreign and Dominion News’ column, edited by Harry Golombek, on page 6 of the January 1954 BCM:

‘Whilst on this subject of confusion it is perhaps worth pointing out that the Golombek who won the championship of Aschaffenburg so easily recently, with the score of 12 points out of 13, is not H. Golombek of England. Nor, as far as we know, is there any relationship – the name, though a rara avis here, is fairly common in Poland, Czechoslovakia and North Germany. Those of our readers who have read War with the Newts by that great Czech writer Karel Čapek may recall that mention is made there of an editor named Golombek.’

(10902)