The last time American theatres faced a crisis of contraction anything like the one they’re facing now—with significant layoffs at New York City’s Public Theater and Dallas Theater Center, season “pauses” at L.A.’s Mark Taper Forum and Chicago’s Lookingglass Theatre Company, emergency fundraising at Oregon Shakespeare Festival and Westport Country Playhouse, not to mention a cascade of closures (detailed below)—it was in the midst of the Great Recession that began in 2008. A previous dip was felt after the 9/11 attacks, particularly in New York City. Before that, in the early 1990s, a downturn in theatre activity was linked not only to economic recession but to the retreat of federal arts funding in the face of sustained political attack.

Now, despite some puzzling economic signals and real inflationary pressures, and despite our ongoing commitment to Ukraine’s defense, the U.S. is decidedly neither in a recession nor a war. So why has our theatre field contracted so precipitously in the past few months, with casualties recorded at every kind of theatre—children’s companies, experimental storefronts, LORT powerhouses, midsize performing arts centers, destination theatres—while at the same time many theatres, and not just on Broadway, continue to post encouraging box-office numbers and seem to be carrying on more or less as before? Is it all down to the rocky recovery of live audiences after COVID closures? To programming that audiences are rejecting or indifferent to? To inherent problems in the nonprofit business model, or faulty management practices? To drops in donated income from governments, foundations, corporations, and individual donors?

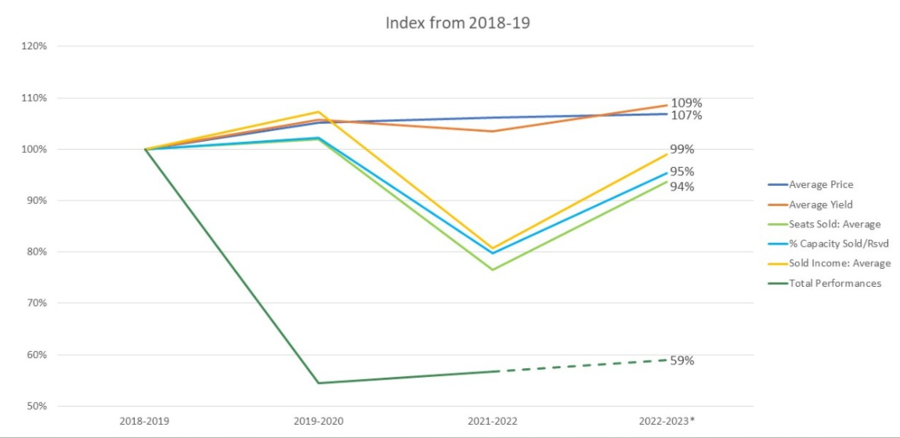

These aren’t just academic questions, of course, but practical and existential ones for theatres pondering anew not only how to make theatre but who they’re making it for and why. The full answers to these questions will be as complicated and various as the nation’s theatres. But a few generalizations can be ventured. First, it is clear that the contraction we’re seeing now actually started last summer—or, more precisely, it could be said that last year’s return to full, post-reopening programming after two years of closure was not in fact full at all. Based on our own data, gathered for last fall’s season listings, TCG member theatres programmed about 40 percent fewer shows in 2022-23 than they had in the 2019-20 season. A new chart from a study by JCA, an arts marketing firm, shows this disparity starkly. While ticket revenue and audience capacity has bounced nearly fully back for the shows on offer, the inventory of shows and performances is down by almost exactly the same number we recorded last fall:

A field that is putting that much less work onstage—and we have reason to believe that the number of shows slated for the 2023-24 season is unlikely to be much bigger, and may possibly be even smaller—is by definition a shrinking field. And so a lot of the contraction we’re seeing is a kind of brutal right-sizing, resulting in layoffs, cancellations, and closures that will have recessionary ripple effects on local economies everywhere from Ashland, Ore., to Brooklyn, not to mention giving a brimming national talent pool fewer entry points.

But if theatres are responding rationally to a drop in demand with a commensurate drop in supply, that doesn’t answer the question of why audience demand fell off a cliff. Zannie Voss, who as director of SMU DataArts studies audience trends, told me that a key difference between this crisis and the Great Recession of the late 2000s is that then, “People were still going about their daily lives and holding on to most of their habits, even if they didn’t have as much cash to spend. The pandemic was a hard stop button on life. And over the course of two years, people changed their habits, their behaviors, their preferences, and the way they consume arts and culture. It’s a shift in consumer behavior.”

Jill Robinson at TRG Arts, an arts analysis and consultancy firm, broadly concurred.

“What’s different from the Great Recession is that, in that case, ticket buying came back pretty quickly, though philanthropy was hit really hard at that time,” said Robinson, whose recent data also show that donations to theatres are down by as much as 40 percent this past spring from pre-pandemic levels. Though Robinson said she was reluctant to generalize about what was making the difference between struggling and thriving theatres, she ventured that too many theatres “allowed the engine to stall” during the COVID shutdown, meaning their engagement with subscribers, donors, and community partners. “If you think about databases as a revenue engine, the longer we let those stale out, the harder it’s going to be to reignite it. And theatres let that stale out, in the macro view, longer than other genres did.”

It’s definitely true that live music revenues surged back stronger than ever (and pointedly, earlier than theatres reopened), even as streaming options made staying home all the more appealing. While the appeal of couch-surfing Netflix et al. over leaving home has been reiterated ad nauseam, Alan Brown of WolfBrown, an arts research and planning consultancy for nonprofits, put a finer point on it.

“When you think of all the popular, excellent drama on television, that is potentially sating public interest in drama,” said Brown. “So the real question is, if you define yourself as being about buying tickets and sitting down and shutting up and watching live drama—it’s just not mapping to the ideal experience of what younger people want to do in their precious entertainment time.”

Most of these researchers and consultants corroborated what we’ve been hearing anecdotally for the past year: that when audiences do consider going to the theatre, by and large they are craving fun, diversion, celebration, spectacle—uniquely theatrical material they can’t get easily at home. Of course, these criteria can mean many different things to different theatregoers. So in the next section we’ll drill down on the highly contested question of what role programming is playing in theatres’ relative success or failure. Next we’ll consider the state of fundraising, particularly at theatres doing it on an emergency, “save our theatre” footing. Then we’ll look at whether the entire nonprofit business model needs an overhaul, and if so, what the alternatives are.

And we’ll close with a forward-looking note, because as difficult as this moment is for specific theatres and theatre workers, live theatre as an art form is not in danger of disappearing from the face of the earth, as theatres all over the country are proving every night (and afternoon). Figuring out what forms this shape-shifting practice will take next—and who will get to make and enjoy it—has always been the work of this magazine, and will continue to be as long as folks gather in person to entertain each other.

Get With the Program

In conversations in recent months with theatre leaders, we’ve heard a few consistent refrains about how the 2022-23 season played out. The most common takeaway: Holiday shows killed at the box office last December. We repeatedly heard phrases like “highest-grossing in the theatre’s history.” This confirms not only the general sense that audiences are mostly craving comfort and joy, but also the grim reality that last winter was the first in three years that didn’t see a COVID surge.

We also heard about some other bright spots: that familiar titles like Clue did well at the box office (not for nothing was it one of last season’s most-produced plays), but also that some newer plays caught on with audiences via word of mouth. The leaders of Atlanta’s Alliance Theatre recently hailed their successful A Christmas Carol but also told us that Katori Hall’s Pulitzer-winning The Hot Wing King was a box-office hit in February. The Repertory Theatre of St. Louis reported a similar pattern with their Christmas Carol and their February show, Dominique Morisseau’s Confederates.

Arena Stage’s Molly Smith said in a recent interview that the highs and lows of the past year have been “extreme. It’s either a boffo hit, with tons and tons of people, or it’s small audiences. You have something like Ride the Cyclone that just did gangbusters, and extended by a couple of weeks; American Prophet did the same. And then there were two other shows that were good shows—but they weren’t events. That seems to be the thing that’s drawing people out of their pajamas right now.”

It’s not as if experimental work isn’t thriving in the right environment: At New York City’s Soho Rep, their spring show Public Obscenities, a new multilingual play by Shayok Misha Chowdhury, extended several times and had standby lines down the street every night (and recently announced presentations at D.C.’s Woolly Mammoth and Brooklyn’s Theatre for a New Audience). That may be why recently departed Soho Rep artistic director Sarah Benson could confidently claim, in a New York Times exit interview, “People want to see ambitious work and things they haven’t seen before. They want to be challenged.”

One strain of criticism you’ll hear from some audience members and critics about the current crisis is that too many theatres have prioritized racial diversity in their programming in recent years, and so theatre’s predominantly white audiences are voting with their feet because they don’t want to go to the theatre to be “lectured” about injustice (bad news for Brecht, Ibsen, Boal, Odets, or Miller, but that may be an argument for another day). Leaving aside that this critique has little to say about the raft of shuttered theatres compiled at the end of this piece (was Bay Area Children’s Theatre’s programming too “woke”?), it is true that some theatres may have moved into this work a bit ham-handedly. As SMU’s Zannie Voss put it, “The whole racial justice movement of the past few years brought a hard light to the fact that there hasn’t been enough diverse programming over the past decade. So you can say, ‘Okay, all of a sudden, we’re going to do diverse programming,’ and hope to just add water and everyone will come. But it’s like a friendship—it takes time and trust.”

At the Bay Area’s California Shakespeare Theatre, which opted to pause productions in 2023 but has several ambitious recovery plans in the works (detailed in the next section), executive director Clive Worsley did concede that “some legacy diehard Shakespeare audience members weren’t willing to come along for the ride to a more diverse casting and/or politically relevant or perhaps even politically charged adaptations.” But he affirmed the theatre’s commitment to diverse programming on pragmatic terms as much as principled ones. “I think that there will always be some relevance for Shakespeare,” he said, “but not enough in and of itself to float an organization of this size.”

Where’s the Money

Almost by definition, nonprofit theatres rely to varying degrees on donated income, even in the best of times. During the COVID shutdown, they received generous relief funding even as their expenses were down, as they weren’t producing. According to TCG’s Budgeting for Uncertainty: Snapshot Survey 2022, 97 percent of responding theatres applied for and received at least one form of federal relief funds from initiatives such as the Paycheck Protection Program, Employee Retention Tax Credits, CARES Act, Shuttered Venue Operators Grants, American Rescue Plan, and Economic Injury Disaster Loan Program. It is worth noting that some of these programs restricted the use of funds to operations expenses. Also worth noting: Theatres saw a 46 percent drop in expenses from 2017 to 2021, and “positive bottom lines were heavily influenced by contributed and investment revenue, with strong increases in government support,” according to TCG’s 2021 Theatre Facts Report. During this time, non-trustee individuals and foundations were the largest sources of contributed revenue, nearly equivalent to state, federal, and local funding combined.

A comparison to the aftermath of the 2009 recession is instructive: The 2009 Theatre Facts report indicated a 9.7 percent growth in expenses from 2005 to 2009, while theatres saw significant capital losses from endowments and other investments. Though contributed income was at a five-year high in 2009, it did not provide enough of a boost to offset the decline in earned income and growth in expenses. 60 percent of theatres averaged negative profits in 2009.

That was, in short, a more conventional downturn, from which most theatres eventually recovered. By contrast, the COVID shutdown, with its combination of relief funding and drastically reduced programming, was more like the calm before a brewing storm. In the past year, theatres have ramped up production, now subject to new inflationary and labor challenges, just as relief funds have run out and audiences’ preferences have changed. In this context, it’s not hard to understand the financial pressures that have caused many theatres to close, pause, or in some cases, run emergency “save our stages” campaigns.

Among them are OSF’s $7.3 million “The Show Must Go On” effort, launched on the heels of its last artistic director’s departure and now running concurrently with the current five-show season, or the Mark Taper Forum’s full stop to raise funds for a 2024-25 season. Connecticut’s Westport Country Playhouse is currently in the process of a $2 million fundraising campaign, while also preparing for a leadership transition as Mark Shanahan succeeds Mark Lamos as artistic director next March. Like many theatres around the U.S., the company has had to lay off staff and pare down its programming calendar.

As of last week, Westport told us they were approximately 20 percent of the way toward accomplishing their fundraising goal, with major gifts conversations underway that could push the needle in a positive direction. Still, interim managing director Gretchen Wright admitted, “We might not even get through the next three weeks. We have no cash reserves. We basically have a fixed amount of money in the bank that’s just getting smaller and smaller. Unless some of these major gifts come through, we will reach a point of maybe needing to pause operation. We’re kind of at a critical, short-term crisis, with some optimism in the longer-term view. Things look brighter going into 2024, but right now—we might run out of money in a couple of weeks.”

In the meantime, Westport is committed to broadening the playhouse’s offerings beyond traditional live theatre productions, including readings and one-night only shows like comedy, conversations, and concerts.

“It’s a financial decision, but also the board is shifting the identity of the organization and the model to be more of a hybrid presenting and producing model,” said Wright. “So there’s a better balance of revenue and expense, as far as how we’re using our space and what we’re putting onstage. The pandemic kind of exacerbated the realities, but we had declining audiences for several years prior to 2020. There was a need for some new ways of programming here. We kind of had to hit rock bottom in order to realize that we had to completely change how we do what we do.”

Westport surveyed its audiences, asking what would bring them back to the theatre. “Instead of seeking buy-in from them, we’ve heard what they want, and so now we’re adjusting accordingly,” said Wright. “We’re trying to give our community what they want, because we feel that’s the only thing that’s getting the theatre going in the short term.”

Still, she explained that even with a more efficient model, fundraising has been a challenge.

“We had a big drop-off in corporate support that started in 2020,” she said. “It’s been a struggle to bring that back up. Other institutional support for us was typically tied to programming. The more programming we’ve cut, the harder it’s been to get funding from those organizations. I feel that many of them were happy to convert a grant to general operating during the pandemic, but I think that trend is changing. They want money to go to programs, and they’re kind of tired of converting it for canceled programming.”

In collaboration with six other regional theatres in Connecticut, Westport was able to lobby the state government for some small additional grants. The playhouse is also still waiting to receive an employee-retention credit, but that is expected to be the last of the relief funding. At this point, Westport’s future hangs in the balance.

Another company in regrouping mode is the California Shakespeare Theater, which opted to suspend in-house productions in 2023. But the Bruns Memorial Amphitheater won’t be dark for long. When managing director Sarah Williams stepped down in fall 2022, the company seriously considered closure. Then former director of artistic learning Clive Worsley returned to become executive director and offered the theatre another option, based on work that was already happening.

“In 2021, we produced one production of our own, and in 2022, we produced two productions of our own,” explained Worsley, “and the rest of the calendar was opened up to other groups to come and perform under what was called a Shared Light Initiative, where other performing arts organizations in and around the Bay Area were invited to produce their work on our stage for little or no fee.”

Worsley cited theatre companies in the Bay Area that are keeping costs down by sharing patron services, software, IT personnel, and activities. The Cal Shakes scene shop is building sets for Berkeley Playhouse, Shotgun Players, American Conservatory Theater, and other theatre companies. This arrangement not only saves those companies money; it’s also generating revenue that will make it possible for Cal Shakes to produce a marquee production for its 50th anniversary in 2024.

“The idea is that we become a multidisciplinary performing arts venue,” said Worsley, “with Cal Shakes as the resident theatre company at the center of it. Our education programs will continue as before. We will make the space available to other performing arts groups to share the space with their audience, and merge our audiences, and we will also do straight-up revenue-positive rental activities.”

As for the theatre’s fundraising approach, Worsley said, “It’s almost as though what we are right now is a startup, and we are actively going out and looking for capital for this startup.”

This crisis, unfortunately, intersects with larger changes in arts funding patterns. A study by the Arts Funders Forum showed changes in giving behaviors with a “rising generation of donors.” As Forum director Melissa Cowley Wolf put it in a 2020 op-ed, these donors are increasingly “skeptical about the power of the arts to create a better world. Research shows that many of these funders prioritize advancing social, racial, environmental justice and equity; they seek specific, measurable impact; and they embrace technology to solve the pressing issues of our day.”

To recapture these donors, Wolf recommends that arts organizations change the conversation around fundraising to reflect their specific core values, and to take a more active, mission-oriented approach to addressing structural inequities in the field.

This generational shift comes as the nonprofit sector struggles to contend with an overall reduction in donors. Donor participation fell in five out of the last six quarters, particularly among new donors, with a 10 percent decline recorded in 2022, according to the Fundraising Effectiveness Project’s Q4 report. This has caused a reliance on large donations from repeat donors. Calls for renewed federal funding, even a bailout for the theatre industry, have also been heard, though it is hard to imagine the current U.S. Congress considering this seriously.

Surveying this aspect of the crisis, TRG’s Jill Robinson said, “It’s a long game. It’s expensive to create new customers for any business, and we have to create funders who are interested in helping make that happen.” Considering CTG’s decision to pause production at the Mark Taper Forum for a full season and raise money, she said, “I can’t even imagine how hard that is in this environment. To say, ‘Listen, we need to take a beat—we’re committed, but we’ve got to have the financial plans to be able to do this kind of work.’ I think that’s an inspiration, not a failure. This political environment is becoming more open to having the real conversation right now about, what is it going to take to keep the doors open? It takes courageous leaders who say, ‘We’ve got to have financial plans for the next five or 10 years, not for the next 60 days.’”

This Year’s Model

Of course, an effort to bail out theatres as they’ve run for decades side-steps the larger question of whether the nonprofit business model itself is sustainable or in need of a root-and-branch overhaul. When Mara Isaacs left the nonprofit sector to found Octopus Theatricals 10 years ago, it was in no small part because, as she said in a recent interview, “The writing was on the wall” for the business model undergirding the nation’s nonprofit theatres. The structure around how theatre does business, how it funds its work, how it connects to its community, and how it is valued in the larger society simply hasn’t evolved or developed at the same pace as the industries around it.

“I think the business model is severely broken, and it hasn’t changed much in the last 75 years,” echoed Michael Bobbitt, who also left theatre leadership behind him to serve as executive director for Mass Cultural Council. “There are many strained business models out there, but theatres might be the most strained of my arts organizations.”

Bobbitt said moving to a state agency has helped give him a broader perspective of the issues facing theatre since his days in the thick of things (he formerly served as artistic director of the New Repertory Theatre in Watertown, Mass., and of Adventure Theatre-MTC in Maryland). As he considered the issues facing theatre’s business model, he pointed to a conundrum that has challenged organizations from Wiliamstown Theatre Festival to the storefront theatres of Chicago: In the last few years, the industry has pushed for overdue corrections around racial equity, labor, artist treatment, and hiring practices. “All of that added expenses and none of it brought in more revenue,” he said. “So we put more pressure on our theatre companies, more strain on the business.”

To be fair, Bobbitt noted that the nonprofit arts sector across the board is financially unstable—this isn’t just a theatre problem. That’s why, when he looks for solutions and alternatives to the way theatre does business, his eyes turn toward industries outside the sector. Bobbitt said that when he was leading arts organizations, he wouldn’t look to other arts organizations when trying to find remedies to declining subscription numbers. Instead he would eye patron loyalty programs at hotels or airlines, ice cream parlors or coffee shops, zoos or aquariums, to see what he might learn.

In another example, he pointed to the corporate world and wondered if theatres could be more nimble, stepping away from annual budgeting and focusing on a quarterly budget so that annual planning could potentially be more of a roadmap than a requirement.

“We’re asking our artistic directors to program seasons that are six months to 18 months in the future,” Bobbitt said. “It doesn’t leave any room for flexibility. It doesn’t leave us any room to respond to what’s happening in the world. The world is moving way too fast for us to do that kind of programming.”

He pointed to his own past frustrations directing or choreographing a show late in a theatre’s season, worried that a rough first half of the season might result in a theatre’s board pushing to cut expenses, thus threatening the quality of the late-season work. Of course, Bobbitt acknowledged that this temporal shift in thinking would bring its own complications, especially when it comes to securing artists, but he wonders if it might also open the door to a more sustainable way to do theatre. Such a move, Bobbitt ventured, might also open the door for nonprofits to follow a successful habit of the for-profit theatre world—i.e., letting a successful show keep chugging along without the theatre being beholden to their subscription promises.

For her part, Isaacs said she wouldn’t want to see nonprofits follow too closely in the footsteps of commercial theatre, or to scale back to the point of hyper-focusing on the box-office success or failure of one show after another. She said she can already feel “a real risk aversion now in institutions, because there is so much at stake.” This is happening at a time when Isaacs said she’s seeing more and more audiences wanting to curate their own experience; they are increasingly looking for some kind of “guarantee of experience” rather than risk or experimentation. It’s an impulse that can feel antithetical to offering the public a well-curated, year-long vision of a sole artistic director—another model whose time may have passed.

With ticket prices that have historically priced people out, and COVID-era forays into streaming or virtual theatre offerings that were all too quickly abandoned, nonprofits still struggle to reach audiences.

“The pandemic has been an accelerant, but it is not the cause,” Isaacs said. “For whatever reason, our society at large doesn’t value what the arts can do for its communities in the way that I think it used to.”

League of Chicago Theatres executive director Marissa Lynn Ford said the importance of theatre to the community “needs to be reiterated over and over again.” She pointed to theatres impacting the world around them beyond the shows that wind up onstage, be that through educational and other community-centered programming or offerings like training courses for businesses.

As part of her own research, Isaacs has begun looking into the history and reasoning behind 501(c)(3) and why the system is set up the way it is. While she wasn’t quite ready to share her findings, she did point to the role of nonprofit boards. With financial pressures mounting on theatres, boards have become fundraising boards, she observed, rather than the ideal she envisions: a group who is there to protect the mission of the organization, a mission that should be intrinsically tied to the theatre’s community.

“I think that we’re actually at the dawn of a major crisis,” Bobbitt said. “These theatres that have closed or ceased programming, that’s the beginning. If we don’t act now, and we don’t act collectively…”

Bobbitt cut himself off. In 2021, for this publication, Bobbitt wrote about the problem with nonprofit boards, laying out not just the issues with them but potential solutions or approaches for the future. Originally he thought only a handful of folks would read it, but, reflecting more recently, he couldn’t believe how massive the response was as the field reckoned with his thoughts.

“Yet we haven’t done much about it,” Bobbitt conceded.

That seems to be how it goes. Changes, as even Bobbitt observed, have been happening via small conversations, which have led to some theatres tinkering at the margins. But widespread action remains elusive. Even, or perhaps especially, at a time of risk aversion, there’s value in those risk takers, Isaacs said. There need to be some theatres who try something new, who may become the inspiration other theatres around the country may need—or the cautionary tale that leads others to make improvement.

“One of the challenges is that the people who are actually in action don’t have time to do blog posts,” Isaacs said. “Maybe the people you want to hear from are not the people who are raising their hand to speak, because they’re actually in the trenches trying to figure it out.”

So what is the venue for these conversations, and how can those learnings be turned into action on a large scale?

“We need collective impact work,” Bobbitt said. “We need to get together as a sector and hash this out, but we need to hash it out with other people—economists and futurists and entrepreneurs and people that really think about building businesses that are sustainable, who spend all their time working on this kind of stuff. We haven’t figured it out in our sector. We’ve been tweaking and tweaking and tweaking but having the same result. Now we’re seeing theatres closing. We need to ask for help.”

Light a Candle

As we’ve been compiling this feature and the listing of closed companies and programs below, season listings have been pouring in for the 2023-24 at TCG member theatres. If you’re looking for an antidote to despair about the state of the field, you could do worse than take a look through these listings—still in progress as of this writing, but growing in size and scope every day. They paint an incomplete but encouraging picture of a field that is home to a mix of ambition and tradition, new and old, familiar and fantastical.

One particular bright spot we’ve noticed: multigenerational and TYA programming. These are worth doing for their own sake, of course, but they also promise long-tail impact. As Peter Brosius, outgoing artistic director of Minneapolis’s Children’s Theatre Company, told us recently, “People are hungry to provide opportunities for their kids, so our education programs are going gangbusters—they’re selling out faster than ever.” And he made a familiar point with fresh urgency, looking out at a struggling field and noting “the number of regionals who are beginning to make multigenerational programming a part of their life, because they realize that the single best way to build the audience of the future is to start people when they’re young. It’s not gambling. It’s bloody simple. All the studies show that people who have been exposed to the arts and had deep arts experiences when they’re young are so much more likely to engage the arts as audiences, as practitioners, as donors, as patrons, as board members, as staff, than those who haven’t. So we literally see our work not so much as making plays but as sort of guaranteeing a future for the American theatre.”

Indeed, for all the challenges of the present moment, one pressing question for the future is the extent to which theatres are expanding and nourishing audiences and creative talents of tomorrow. A few signal examples can provide an inspiration and a model. At Chicago Children’s Theatre (CCT), the Red Kite Project houses numerous programs for kids with autism, developmental disabilities, and other accessibility needs, as well as for their families. Founded by CCT artistic director Jacqueline Russell, Red Kite is not an afterthought or add-on but is central to CCT’s very founding and mission—“the heart of the company,” as Russell put it.

While many theatres struggle to retain and serve existing audiences, Russell said she spends much of her energy “really trying to convince people that they are welcome here, and we want you here, and there is something for you here. I think there’s a big hesitation from a lot of families that their kid will be too much…We’re seeing families that would like to participate but don’t know if they can.”

Red Kite, which remained busy reaching kids both in Chicago and all over the country during the shutdown, has had no shortage of support for their work as they’ve returned to in-person performance, including funding that has enabled Sam Mauceri, CCT’s current director of education and access programs, to manage the Red Kite Project full-time. With initiatives like a three-week summer Camp Red Kite, weekly after-school classes, and multi-sensory interactive performances that go to parks, libraries and community centers, they have watched kids grow into adults in their programs, even experience true belonging for the first time.

Russell shared, “When we did our first Red Kite performance, we mailed invitations to all the kids in our classroom, and we invited them to come to this performance, and they were the very first audience to see it. This mother came up to me, and she said, ‘My son is 9 and this is the first invitation he’s ever received—to do anything.’ It was so meaningful for them to receive an invitation with his name on it. I never forget that, and I am just very proud of this work because I think every child should get that feeling. And we’re just gonna keep doing that till we get all those kids to come and party with us in this city.”

Meanwhile, at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., Kelsey Mesa, manager of Kennedy Center American College Theater Festival (KCACTF) and Theater Education, said she has “a lot of faith in the future of theatre in the United States, because this next generation of creatives coming up is something special.” Indeed, it may be little known that the Kennedy Center American College Theatre Festival is the prestigious center’s oldest program, predating even its impressive building.

The festival serves eight U.S. regions with around 600 colleges and universities, assembling a cohort of young designers and directors, as well as Irene Ryan Acting Scholarship candidates, for professional development opportunities. Having worked at Kennedy Center for 15 years, Mesa has come across plenty of trailblazers. She cites Austin Dean Ashford, an artist known widely for his work as a musician, writer, and performer who experiments with different mediums; current theatre management MFA candidate Roman Sanchez, an alum through Aspire Arts Leadership, who founded Lime Arts in 2016; and Sis Thee Doll, a powerhouse performer and activist who went from being a KCACTF directing fellow to starring in the recent Oklahoma! Tour as Ado Annie and leading the Trans March on Broadway in 2021. Mesa said, “I have learned from Sis that she puts a lot of energy into activism because she needs to make space for herself in the theatre. We do not have a theatre landscape that has space for everyone. There are people who are not automatically included. It can be hard for people to put so much energy into fighting to just be there when they could be making art.”

Reflecting on the current moment of crisis, Mesa said, “It’s a crumbling of the institution, and it hurts, if you have hung your hat on the institution. It might be seismic. But theatre is not buildings. Theatre is the people, and the people are still gonna be here. So when I think about the challenges, I also think that we can play the long game. We can invest in the next generation in whatever little ways we can. We can advocate for arts education in our schools, and we can support education and outreach programs at theatres. By prioritizing those things, I think the future will be brighter.”

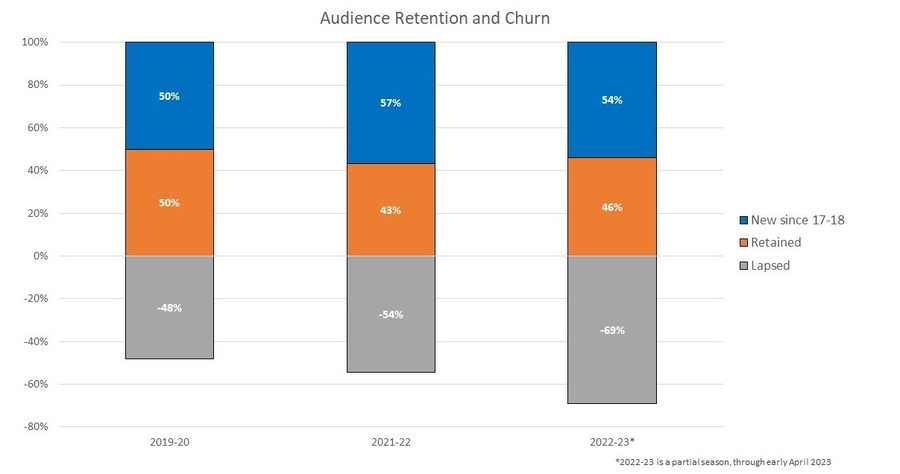

As we began this piece with a chart from the JCA arts marketing firm, we will close with another, showing that more than half of audiences who’ve come back to theatres in the past year are new to the theatre:

Half of an already reduced number of theatregoers is obviously not yet cause for rejoicing. But it’s something to build on.

At Arkansas’s TheatreSquared, managing director Martin Miller presided over a pandemic-era theatre success story, building a new facility and getting national attention with a live simulcast of Designing Women and a co-production of the online play Russian Troll Farm (which garnered the first Obie Award for an Arkansas theatre). But as Miller transitions to the same title at Princeton’s McCarter Theatre Center, the state of the field is much on his mind. He contrasted the current theatre crisis with so many of the rolling disasters we face today, which can make us feel relatively powerless.

“How do we get the bees back? Or what’s going on with wildfires in Canada? You can’t personally go up there and put out the fire,” Miller said. “But when it comes to the crisis in theatre, the solution is in everybody’s hands. I’m not trying to take the responsibility for that solution out of the province of the people making theatre, but people who love it and want to give companies the space to figure out what this next chapter is should drop off a check at their local theatre company, even if they didn’t love the last show. And then they should go and see a play, and then go and see another one.”

Closures Since March 2020

The following list does not include the many theatres that have reduced, cut back, relocated, or paused operations, most of which (but not all) are covered in the story above.

16th Street Theater

Berwyn, Ill., 2007-2022

Who they were: The only professional theatre in Berwyn, and a program of the North Berwyn Park District, 16th Street operated with a budget of over $200,000 pre-pandemic and performed mainly out of a 49-seat basement theatre space in the North Berwyn Cultural Center.

Kind of work they did: The company featured a number of world premieres and rolling world premieres, including Minita Gandhi’s Muthaland, Aline Lathrop’s The Hero’s Wife, Tanya Saracho’s Kita y Fernanda, and Rohina Malik’s Yasmina’s Necklace. The world premieres of Loy A. Webb’s His Shadow and Natalie Y. Moore’s The Billboard both received recognition from Chicago’s Jeff Awards in recent years.

Reason for closure: The company did not immediately give a reason for the company’s closure, which came just over a year after founding artistic director Ann Filmer left the company. In a statement, the 16th Street board said, “We are no longer a program of, or in any way associated with, the North Berwyn Park District. The North Berwyn Park District is the sole owner of the name ‘16th Street Theater,’ and plans to create a children’s theatre with that name at some point in the future.” Prior to the company’s closure, the theatre had been working with the Park District on a move to a former Veterans of Foreign Wars post, which Filmer had previously said was purchased for the company by the Park District. In an interview with the Tribune, interim artistic director Jean Gottlieb said, “The Park District now wants to go in a different direction.”

Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte

Charlotte, N.C., 1989-2022

Who they were: Founded in 1989, Actor’s Theatre of Charlotte’s mission was to produce new works by contemporary playwrights. The company’s original uptown location was demolished in 2016 to make way for an apartment building. ATC found a new home at Queen’s University, but the venue was unavailable for the 2022-23 season. Its budget as of that year was around $795,000.

Kind of work they did: ATC presented revivals and new works confronting major issues facing the city of Charlotte, including gentrification, class mobility, and race. Notable productions included Fun Home and Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill. ATC complemented its tougher works with crowd-pleasers like Rock of Ages and Silence! The Musical.

Reason for closure: In a letter to subscribers, executive director Laura Rice cited “the continuing effects COVID-19 has had on performing arts operations such as ATC, disappointing ticket and subscription sales, and recent news that ATC would be seeking another performance venue.” Challenges in finding a new venue in Charlotte, where development is increasingly focused on business over venue spaces, proved the last straw for an already strained organization.

AstonRep Theatre Company

Chicago, 2008-2023

Who they were: Over the years, AstonRep performed at various venues around Chicago, including the Edge Theatre’s 104-seat proscenium theatre and black box theatre, and Raven Theatre’s 56-seat Schwartz Stage, among other small rental venues.

Kind of work they did: AstonRep typically produced two shows per season alongside its annual Writer’s Series, a festival that provided Chicago, national, and international playwrights the chance to workshop plays with AstonRep actors and guest artists. The company received a Jeff Award nomination for best short run production in its final season for its production of Sam Shepard’s Buried Child. They also produced the world premiere of Warren Hoffman’s The Black Slot and Chicago premieres of Deborah Brevoort’s The Women of Lockerbie, Nicky Silver’s The Lyons, Geoffrey Nauffts’s Next Fall, and Theresa Rebeck’s The Water’s Edge.

Reason for closure: When AstonRep announced its 2022-23 season, it presented this 15th season of producing theatre in the city as its last. In a recent interview, founder Robert Tobin said, “The last two, three years have become very tough for a number of factors,” including becoming more difficult to raise money. Though running a storefront in Chicago, especially over the last few years, was challenging, Tobin said it was also rewarding. Ultimately, Tobin said, “We just decided 15 years was a good number, and maybe it was time to move on.”

Atlanta Lyric Theatre

Atlanta, 1980-2023

Who they were: Founded in 1980 as the Southeastern Savoyards, an operetta repertory company, the Lyric was the only professional musical theatre company in Atlanta until 2016. Since 2013 the company made its home at the Jennie T. Anderson Theatre on the Cobb Civic Center Complex, a 600-seat venue which, prior to the pandemic, the Lyric regularly sold out.

Kind of work they did: The Lyric presented Broadway standards, from My Fair Lady to Rent, as well as lesser-known musicals like The IT Girl. They also collaborated with the Jennie T. Anderson Theatre on drive-ins, festivals, and one-night concerts. Many young performers got Equity cards through Lyric productions, while Broadway talent would sometimes come out to Atlanta for a Lyric run.

Reason for closure: The Lyric closed in March, citing financial strain and insufficient funding to either complete its 42nd season or embark on a 43rd. Confronted with these financial challenges alongside dwindling audience numbers, the Lyric’s board voted to dissolve the organization. Remaining productions in the season, including Pippin, were canceled. Frequent performer Galen Crawley told ArtsATL: “It is heartbreaking that the board would vote to dissolve instead of mounting a capital campaign or signaling, in some way, that they needed help.”

Bay Area Children’s Theatre

Oakland, Calif., 2007-2022

Who they were: Founded and run by Nina Meehan for most of its run, the theatre had a budget of approximately $750,000 as of 2021, a year after Khalia Davis was named artistic director. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that BATC had hoped to raise as much by the new fiscal year on July 1 with their Save Our Stage campaign, which they announced in early May.

Kind of work they did: As their name suggests, Bay Area Children’s Theatre staged Theatre for Young Audiences shows and other family-friendly fare. They were known for adapting popular children’s books for the stage, including The Very Hungry Caterpillar. They also produced shows targeted for the interests (and attention spans) of toddlers and ran robust youth arts education programs.

Reason for closure: The theatre announced their abrupt and immediate closure on May 17, reporting that patron donations for the Save Our Stage campaign were insufficient to cover the theatre’s operating costs due to “growing, insurmountable financial burdens” (and despite the fact that their 2022 ticket sales were up 9 percent from 2019). Like many theatres that have closed or paused programming, BATC cited the financial impact of the COVID shutdown in their decision. Christina Clark Bloodgood, the outgoing board president, told the Chronicle’s Lily Janiak that many Bay Area actors the company relied upon had been priced out of the area and now required the theatre to pay to house them.

Berkshire Playwrights Lab

Great Barrington, Mass., 2007-2021

Who they were: Founded by Joe Cacaci, Jim Frangione, Bob Jaffe, and Matthew Penn, Berkshire Playwrights Lab provided opportunities for writers to encourage, develop, and present new plays. A Staged Reading Series gave playwrights an intensive four-day rehearsal process ahead of a free public reading. BLP also launched the Radius Playwrights Festival and the Berkshire Voices program to cultivate and encourage theatrical talent in the local area.

Kind of work they did: BPL developed work by acclaimed playwright James Anthony Tyler and produced his play Some Old Black Man in New York in 2018. (Tyler also became a co-artistic director of the festival.) The festival also developed Jane Anderson’s Mother of the Maid, which was then produced by Shakespeare & Co. in Massachusetts and the Public Theater in a production starring Glenn Close.

Reason for closure: BPL presented a virtual festival in 2020 but remained dark in 2021. The festival was unable to remain financially viable without resuming full operations, and announced its closure later in 2021.

BoHo Theatre

Chicago, 2003-2023

Who they were: With a typical storefront model, BoHo staged works in rental venues like the Edge Theater. In pre-pandemic times, their season featured between three and five mainstage productions plus special events.

Kind of work they did: Inspired by the bohemian pillars, BoHo facilitated a warm, family-friendly atmosphere in both process and product, producing both established musicals like Big Fish and new plays by emerging writers.

Reason for closure: BoHo had already called off spring 2023 programming, but realized after a January board meeting that they would not be able to secure the funds to both sustain a theatre season and pay workers beyond 2023. The company closed after investigating many options (which included downsizing the season and merging with another nonprofit).

Book-It Repertory Theatre

Seattle, 1990-2023

Who they were: Founded in 1990 by co-artistic directors Jane Jones and Myra Platt, Book-It transformed literature into theatre. Their productions reached 60,000 K-12 students in Washington schools annually. Their budget last year was nearly $1.6 million.

Kind of work they did: Book-It employed a unique style of theatrical production, with the text of literary works spoken as well as staged, and prose narration recited by actors alongside a character’s dialogue. The company adapted countless classic novels, including Moby-Dick, Pride and Prejudice and Howards End. Book-It also adapted contemporary novels by local authors. Book-It’s final production was David Greig’s adaptation of Solaris, based on the novel by Stanislaw Lem.

Reason for closure: Book-It announced that it had ceased operations in June. Founders Jones and Platt had stepped down in 2020 to make way for new leadership, and a number of personnel changes followed: managing director Kayti Barnett-O’Brien left in 2022, and new artistic director Gus Meaneary announced his own departure in April. Interim artistic director Kelly Kitchens and Book-It’s board determined that decreased ticket sales, limited individual giving, and increased production costs made future seasons unfeasible. “We all still believe in the art form and can’t help but hope that we will see a show in the Book-It narrative style on a Seattle stage again,” board secretary Becky Monk said.

EXIT Theatre

San Francisco, 1983-2022

Who they were: EXIT Theatre was born when founding artistic director Christina Augello staged a new play in a hotel lobby in the Tenderloin neighborhood, casting locals from the area. Though EXIT grew and came to operate two venues in San Francisco, it always retained an experimental focus, providing a home for vaudevillians, improvisers, and magicians. Walking in to EXIT on a given night, you might find a play to your left and a burlesque show to the right.

Kind of work they did: San Francisco Chronicle theatre critic Lily Janiak praised the company’s “devotion to the new and the now, the weird, and the wild.” Significant productions have included works by resident playwright Sean Owens including Odd By Nature and Naught But Pirates, and Waiting for FEMA by Karen Ripley and Annie Larson. EXIT also founded the annual San Francisco Fringe Festival in 1992, and its sister venue still hosts the festival annually.

Reason for closure: EXIT closed its flagship venue on Eddy Street in 2022 due to rising costs and shrinking audiences post-reopening. Augello moved north to Arcata and now programs out of a 35-seat space, another EXIT outpost, and a sister venue Exit on Taylor remains open, subleased to other companies with the exception of the Fringe Festival, still hosted at Taylor, for which Augello returns to San Francisco to program. This year’s festival runs Aug. 10-26.

First Folio Theatre

Oak Brook/Chicago, 1997-2023

Who they were: Known for performing in the impressive Mayslake Peabody Estate, First Folio offered “high-quality performances to the Chicagoland suburbs” with attention to audience experience. As of 2021, their budget was close to $255,000.

Kind of work they did: First Folio began to fill a gap in directing opportunities for women and non-musical theatre work. In the summers, Shakespeare productions would draw artists and audiences to their outdoor venue, but their indoor space featured both contemporary and classical works year-round.

Reason for closure: In late 2021, First Folio shared plans for a 2024 closure, with co-founder and executive director David Rice citing financial trouble sustaining a full-time staff and being eligible for Chicago theatre grants. But early 2023 brought compounded difficulties that led them to cancel their final productions.

foolsFURY

San Francisco, 1998-2021

Who they were: As its name may indicate, foolsFURY was an adventurous company focused on ensemble-oriented experimental work. The troupe produced both original works and deconstructed classics, and allowed its artists longer periods of development, inviting audiences into the process and showing works at various stages of development. SF Arts Monthly once hailed the company as “one of the brightest stars of the San Francisco experimental theatre scene.”

Kind of work they did: foolsFURY first garnered wide attention with the world premiere of Monster in the Dark by Doug Dorst in 2008, a co-production with Berkeley-based Shotgun Players. It was followed the next year with the U.S. premiere of Fabrice Melquiot’s The Devil on All Sides, which toured from San Francisco to Performance Space New York (formerly P.S. 122). foolsFURY has supported many new playwrights through new commissions, including Sheila Callaghan, Katie Pearl, Angela Santillo, and Kate Tarker.

Reason for closure: foolsFURY cited multiple factors in its decision to close: the 2020 departure of founding artistic director Ben Yalom, the 2020 wildfires that destroyed the Sonoma County home and artist retreat center of current artistic director Debórah Eliezer, and the COVID-19 pandemic, which destabilized the small and nomadic company’s infrastructure. foolsFury’s “Legacy Project,” a thorough archive of the company’s work and history, is now available on the company’s website.

House Theatre

Chicago, 2001-2022

Who they were: Founded by creatives from Southern Methodist University and the British American Drama Academy, this ensemble-based theatre was known for critically acclaimed, risk-taking adaptations and new work. After 2021, the company had planned to execute a much-anticipated anti-racist action plan.

Kind of work they did: A Chicago staple, the company memorably staged Death and Harry Houdini, The Terrible Tragedy of Peter Pan, The Hammer Trinity, United Flight 232, and more. Countless artists in the area had crossed paths with this company.

Reason for closure: Board president Renee Duba’s statement read, “We did not have the financial momentum or audience/donor support to continue beyond this fiscal year. We chose instead to maximize our current year programming and to honor all present commitments and partnerships with a thoughtfully planned exit from the Chicago theatre scene.”

Humana Festival of New American Plays

Louisville, 1976-2021

Who they were: Founded in 1976 by director Jon Jory, the Humana Festival of New American Plays was a world-renowned festival presented by Actors Theatre of Louisville which celebrated the contemporary American playwright. It was sponsored by Humana, a health insurance company based in Louisville, starting in 1979. A wide array of world premieres, usually six to 10 plays, were presented over multiple weeks in a flurry of new work which attracted artistic leaders from around the world to Louisville.

Kind of work they did: Humana hosted premieres by Will Eno, Sarah Ruhl, David Marguiles, Beth Henley, and Brandon Jacobs-Jenkins. Many Humana premieres went on to major productions and significant acclaim, such as Becky Shaw by Gina Gionfriddo and The Christians by Lucas Hnath. Obie-winning director Les Waters ran the Actors Theatre and curated the festival 2012-2018.

Reason for closure: The Humana Festival was canceled in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, then presented in virtual form in 2021. In March 2022, Actors Theatre confirmed the festival would not be held that year, citing a need to “reimagine a 21st-century model that is sustainable, equitable, and radically accessible,” according to artistic director Robert Barry Fleming. Humana confirmed that their funding relationship with Actors Theatre had ended. Fleming said the festival could return in a different form, but that Actors Theatre was focused on year-round new-play development programs.

Interrobang Theatre Project

Chicago, 2010-2023

Who they were: With a pre-pandemic budget of around $70,000, Interrobang was in residence at Chicago’s Rivendell Theatre, performing in Rivendell’s 50-seat black box theatre.

Kind of work they did: Interrobang’s mission was to produce rarely produced texts and new American plays, work they hoped would excite a new generation of theatregoers and engage the community. In 2019, the company won Broadway in Chicago’s Emerging Theatre award. Highlights from their 13-season run include the world premiere of Calamity West’s Ibsen is Dead, the U.S. premiere of Elinor Cook’s Out of Love, and Chicago premieres of Deanna Jent’s Falling and Dawn King’s Foxfinder. Interrobang received Jeff Award nominations for best production of a play for their stagings of Foxfinder and Rajiv Joseph’s The North Pool.

Reason for closure: In a statement announcing the end of the company’s run, Interrobang cited “a shrinking board, staff, and ensemble due to pandemic-related pivots, hiring challenges, and shifting expectations surrounding pay and sustainability.”

The Lark

New York City, 1994-2021

Who they were: Formerly Lark Play Development Center, the Lark was an international theatre laboratory dedicated to discovering and developing playwrights. Founded by John Clinton Eisner, the Lark sought to nurture American and international artists at all career stages by providing resources such as money, space, collaborators, audiences, professional connections, and the freedom to design their own processes of exploration. As of 2022, the Lark had an approximate budget of $1,371,708.

Kind of work they did: The Lark hosted the Playwrights’ Week new work festival, various writers’ retreats, workshops, readings, roundtables, fellowships, and international exchange programs. It sought to be an artistic home for new voices and new ideas.

Reason for closure: According to a statement from Oct. 2021, the Lark board of directors voted unanimously to end operations citing “no sustainable and viable path forward” for the organization financially. The Lark’s financial model depended almost entirely on individual and institutional giving. Members of the playwriting community, including former director of development Nora Brigid Monahan, questioned the board’s account, referencing issues of mismanagement, neglect, and gaslighting, as well as conflicts between the board and artists. Several of the Lark’s key programs were rehomed to other theatres.

Lincoln Center Theater Directors Lab

New York City, 1995-2022

Who they were: The Lincoln Center Theater Directors Lab was a developmental program for stage directors from around the country and the world. Founded by former LCT dramaturg Anne Cattaneo, the Lab combined approaches from directing, dramaturgy, different types of work, and different cultures. Intentionally non-academic, the Lab was geared toward professional directors in early career stages and was free of charge. Members were accepted based on the stories and ideas written in applications. More than 1,600 directors went through the program.

Kind of work they did: The Lab was an intensive, six-day-a-week, 10-hour-a-day, three-week program of workshops, shared sessions, rehearsals, investigations, theatregoing, and discussions with accomplished and well-known artists. The LCT Directors Lab was nominated twice for a Tony Award. The Lab had sister programs based in the North, West, and Mediterranean regions, as well as in Chicago.

Reason for closure: After the last gathering of the Lab in 2019, Cattaneo was planning a 2020 iteration, then scotched by COVID. The Lab’s offices never reopened, she said, and in 2022, considering among other issues the Trump Administration’s travel policies, which complicated access for international directors, she decided to retire. LCT has said that they intend to continue the Lab’s work in some form in the future.

MainStreet Theatre Co.

Rancho Cucamonga, 2006-2020

Who they were: MainStreet Theatre Company presented theatre for young audiences at the City of Rancho Cucamonga’s Lewis Family Playhouse for 14 years. Led by Mireya Hepner, the company’s founder and sole employee, MainStreet was heralded for mature, artfully crafted productions which “happened to be stories kids could come to,” as Hepner put it. Shows starred Equity actors and were directed/designed by respected “adult” theater artists from the area.

Kind of work they did: MainStreet shows were typically adapted from popular children’s book titles. Notable productions included A Wrinkle in Time, Miss Nelson Is Missing, new play Aesop in Rancho Cucamonga and the company’s final production, And Then They Came Me: Remembering the World of Anne Frank. Hepner’s work aimed to never talk down to young audiences—programming was challenging and talkbacks ensured kids engaged deeply with the questions raised by each show.

Reason for closure: Hepner was technically an employee of the City of Rancho Cucamonga, which operated MainStreet’s former venue, and her position was eliminated by the city in May 2020 as part of cuts forced by the Covid-19 shutdown. At the time, the City Council stated that the theatre was not dissolved and would return at some point, but it currently remains inactive.

Metropolitan Playhouse

New York City, 1993-2023

Who they were: Since 1993, Metropolitan Playhouse has presented small-scale productions along with readings, workshops, and chamber concerts, becoming a modest Off-Off-Broadway institution. The company brought renewed attention to over 100 forgotten American plays. Since 1997, Metropolitan Playhouse has made its home in a 51-seat theatre on the second floor of the Cornelia Connelly Center in the East Village. The company received a 2011 Obie grant from The Village Voice and a 2014 Outstanding Performing Arts Group Award from the Victorian Society of New York.

Kind of work they did: Metropolitan Playhouse’s first production was Dion Boucicault’s rarely revived melodrama The Poor of New York. Beginning in 2001, each season tackled a particular theme: Faith, Starting Over, The American Dream, etc. The Playhouse operated under the Equity Showcase Code, which permits brief runs for minimal compensation. The theatre placed particular focus on its neighborhood’s culture and history, presenting the Alphabet City Monologues (based on interviews with the theatre’s neighbors) and the East Village Chronicles (one-act plays inspired by the area).

Reason for closure: Producing artistic director Alex Roe stated that the Playhouse had “reached the limits inherent in a company of our small size, and it is time to draw the curtain.” Roe left the door open to future productions based on a different funding model. For now the theatre will focus on creating an easily accessible online archive of their history.

The New Coordinates

Chicago, 2008-2023

Who they were: Formerly known as The New Colony, The New Coordinates didn’t have a permanent home and innovated modalities to accommodate new-work development pre-, during, and post-pandemic. They were known for gathering writers everywhere from a bar to the Den Theatre.

Kind of work they did: With every production slot reserved for new work created from scratch, their mission emphasized newness in the makeup of art, artists, and audiences.

Reason for closure: After a challenging year of not finding financial footing in the return to in-person programming, former co-artistic director Fin Coe lamented that the company had to cancel its final production a week before tech. In retrospect, he wishes that smaller companies had clearer pathways to survive, grants had fewer applicant limitations, and TNC had cultivated stronger ties with its location/community.

New Ohio Theatre

New York City, 1993-2023

Who they were: A supporter and presenter of New York City independent theatre companies creating bold new work, New Ohio began life as the Ohio Theatre in 1993 and initially operated in a warehouse in SoHo. In 2011, the company moved into their space on Christopher Street in the West Village and became the New Ohio Theatre, renovating and improving the 74-seat space while giving a home to 100-plus experimental new works by emerging artists.

Kind of work they did: New Ohio hosted productions from terraNOVA Collective, Page 73, The NeoFuturists, the Assembly, Vampire Cowboys, Bedlam, Untitled Theater Company No. 61, Blessed Unrest and many more. Annual programs included the Ice Factory Festival, Now In Process and The Archive Residency (co-run by IRT Theatre).

Reason for closure: Artistic director Robert Lyons cited increasing financial pressures in closing the New Ohio as of August 2023. Lyons also felt it was a good time to hand off artistic control to a new generation of artists. Alongside the closure announcement in February, the building’s landlord began accepting proposals for a new company to take up residency; no further update has yet followed.

Rep Stage

Columbia, Md., 1993-2023

Who they were: In residence at Howard Community College, Rep Stage received funding from the Howard Arts Council, the Maryland State Arts Council, and the county and state governments, in addition to individual donors.

Kind of work they did: Rep Stage produced both classic and contemporary plays and musicals for audiences in the Baltimore-Washington, D.C. area. Their farewell production, William Finn and James Lapine’s musical Falsettos, closed in May. “Today I choose to focus on gratitude and celebrate the work of the incredible artists who trusted me, journeyed with me, played with me, laughed with me, cried with me, took risks for me, and celebrated the power of theatre,” artistic director Joseph W. Ritsch wrote on Facebook on his last day at Rep Stage.

Reason for closure: Rep Stage announced last November that Howard Community College would be shutting down the theatre at the end of the academic year. DC Theater Arts said that the decision “will allow the college to refocus funding to programs and services that directly serve students.” However, many students in the college’s Dance, Theatre, & Audio Video Production department worked on Rep Stage shows.

PianoFight

San Francisco/Oakland, 2007-2022

Who they were: PianoFight was a community-driven independent arts venue which partnered with local artists to present a wide variety of work in two intimate theatres, while also offering food and cocktails. The company hosted 1,500 performances for over 50,000 audience members in a given year. During the day, its spaces were used as offices and classrooms for community nonprofits. PianoFight had one space on Taylor Street, in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco, and a second in downtown Oakland.

Kind of work they did: PianoFight welcomed music, comedy, dance, drag, film screenings, magic, variety shows and more–as described in the San Francisco Chronicle, its two spaces hosted “everything from a taping of a podcast about menstrual periods, a dating show aimed at disrupting dating apps, and the San Francisco Neo-Futurists‘ whirlwind 30 plays in 60 minutes.”

Reason for closure: PianoFight reopened both of its spaces in February 2022, but struggled with low ticket and bar sales. When the company learned it would be getting less money than expected from the California Venues Grant Program, the decision was made to close up shop.

The Right Brain Project

Chicago, 2005-2020

Who they were: Many of the troupe’s performances took place at RBP Rorschach, an intimate space tucked away in Chicago’s Ravenswood neighborhood that sat around 20 audience members for each performance.

Kind of work they did: Named the Chicago Reader’s “best Off-Loop theatre company” in 2013, the RBP strove to present “startlingly intimate, proudly raw, and innately political” works that reflected the passions of both the company’s artists and Chicago audiences. Production highlights include the Midwest premiere of Virgilio Piñera’s Electra Garrigó, Oscar Wilde’s Salome, Peter Weiss’ Marat/Sade, a Euripides adaptation in The Bacchae Revisited, and the world premieres of Terry Boyle’s Lured: The Curse of Swans and Michaela Heidemann’s Odessa.

Reason for closure: The Right Brain Project announced its permanent closure in September 2020, stating that “subsisting as a small nonprofit theatre has never been easy,” but the new challenges presented during the pandemic gave the theatre “a challenge outside of the RBP’s current capacity.” The statement goes on to say that the company was seeing this as an opportunity “to forge new creative families.”

San Diego REP

San Diego, 1976-2022

Who they were: Founded in 1976 by Sam Woodhouse and D.W. Jacobs, San Diego REP grew out of the street theatre company Indian Magique. The Rep’s mission has been to produce intimate, provocative, and inclusive theatre and to promote an interconnected community through progressive political and social values. The company first made its home at Sixth Avenue Playhouse, a space inside a church in downtown San Diego, before moving to a larger venue, the Lyceum, which the city had planned to tear down. The Rep’s success in drawing audiences convinced the city to instead upgrade and expand the theater, reopening it in 1986 with a 500-seat mainstage and a smaller flexible space.

Kind of work they did: The REP produced or hosted over 500 events at the Lyceum each year. New plays, reimagined classics and experimental work filled their seasons, along with numerous festivals including the Latinx New Play Festival, Black Voices Reading Series, and Kuumba Fest, a festival of African and African American performance. The REP received a 1998 Tony nomination for It Ain’t Nothin’ But the Blues. Other notable productions include the West Coast premieres of American Buffalo and K2. Whoopi Goldberg was a regular on the Rep stage in its early years, and returned in 1993 for a two-night benefit.

Reason for closure: In June 2022, the Rep canceled all remaining productions for the year and laid off all staff, citing low ticket sales, costs associated with recent flooding, operating amidst an active construction zone, and the loss of major donors. The Lyceum Theatre is owned by the city and continues to host other events. “Our goal is to bring the REP back stronger, to continue making provocative, progressive theatre, and we’re working toward this future,” artistic director Woodhouse, who had retired in February, said in a statement.

Sideshow Theatre

Chicago, 2008-2023

Who they were: A non-Equity theatre company that operated out of rental spaces, Sideshow staged plays in Chicago’s more intimate spaces with diverse ensembles. They featured an in-house commissioning/new-play development program called The Freshness Initiative and annually hosted the Chicago League of Lady Arm Wrestlers.

Kind of work they did: Their site emphasizes a passion for “theatre for the curious,” an alchemy of new plays, adaptations, and stories “to mine the collective unconscious of the world.”

Reason for closure: Their farewell messages cited several contributing factors: a canceled 2022 gala, departure from their longtime home at Victory Gardens, and the naturally diverging lives of company members.

Single Carrot Theatre

Baltimore, 2007-2023

Who they were: Founded by a group of theatre artists from Colorado who planted roots in Baltimore, the company expanded and moved from the city’s arts district of Station North to Waverly, where they were in residence at the church Saint John’s in the Village. Their budget was approximately $571,000 as of 2021.

Kind of work they did: Single Carrot was known for immersive works and collaborations with international artists and companies, including Belarus Free Theatre. In 2017, they produced the celebrated original work Promenade: Baltimore in a collaboration with Stereo AKT of Budapest. The show took audience members on a bus journey through city streets as actors performed on sidewalks. In 2021, the pandemic took the company outside again in Keep Off the Grass: A Guide to [Something] on the grounds of Saint John’s.

Reason for closure: In their January announcement of closure, Single Carrot cited multiple contributing factors, including the planned departures of artistic director and founding company member Genevieve de Mahy and executive director Emily Cory. The theatre has also struggled with “staffing shortages and stretched human capacity” since the onset of COVID and wrote on their website that they “could not offer fair compensation to bring in artists and staff members and keep them.” Prior to announcing their closure, Single Carrot also postponed a production of Aziza Barnes’s play BLKS, due to potential mistreatment of Black members of the cast and artistic team. “Single Carrot’s inadequate communication resulted in the direct harm to Black artists, which is antithetical to our mission and values,” the company wrote in a December email. The company recently published a 42-page impact report on its work and legacy, which states that the theatre staged 33 world premieres and commissioned 24 works over its 15 years.

The SITI Company

New York City/Saratoga Springs, N.Y., 1992-2022

Who they were: A troupe of like-minded artists who came together around the theatre teaching of Tadashi Suzuki and the Viewpoints-influenced work of director Anne Bogart, SITI Company was known both for its rigorous physical training and for a body of experimental, ensemble-driven stage work. Among other venues, they performed frequently at Brooklyn Academy of Music, Wexner Center for the Arts, and Actors Theatre of Louisville.

Kind of work they did: With playwrights like Charles Mee Jr., as well as in ensemble-created works, adaptations of classics, and collaborations with dance and opera companies, SITI forged a unique presentational aesthetic influenced equally by the physical forms of Suzuki and the spatial/improvisational spirit of Viewpoints. Major works included bobrauschenbergamerica (with Chuck Mee), Steel Hammer (with composer Julia Wolfe), Death and the Ploughman, and Room (inspired by Virginia Woolf).

Reason for closure: SITI considered ways to continue and/or merge with other companies, but ultimately decided to cap their 30 years as a company with a final celebration and production. A complete archive of their work is available at the Lawrence and Lee Theatre Research Institute at Ohio State University.

Southern Rep

New Orleans, 1986-2022

Who they were: Originally located in Canal Place, a multilevel shopping center at the foot of Canal Street, the company later took up residence at Loyola University New Orleans, and then, in 2019, moved into a permanent home inside the former St. Rose de Lima church in the historically Black neighborhood of Treme.

What kind of work they did: Seeking to present a selection of new works and classics that spoke to the New Orleans community, they did their share of Tennessee Williams, of course, but also a mix of new and old plays, including works by Taylor Mac, Sarah DeLappe, and Ntozake Shange.

Reason for closure: In the move to Treme, the company lost a certain portion of its long-standing white audience, then failed in their efforts to build relationships with the Black community, with some employees speaking publicly about racialized trauma in the transition. A silver lining: The former St. Rose de Lima Church has since reopened as the André Cailloux Center for Performing Arts & Cultural Justice (ACC New Orleans), a Black-led, BIPOC community-serving, multi-tenant, performance art and cultural justice venue.

St. Luke’s Theatre

New York City, 2006-2021

Who they were: Saint Luke’s Lutheran Church on 46th Street between 8th and 9th Avenues, in the heart of Hell’s Kitchen, includes an intimate 175-seat theatre in its basement. Beginning in 2006 it was run by producer Edmund Gaynes, who dubbed the space St. Luke’s Theatre. Gaynes programmed a wide array of simply staged crowd pleasers which performed in repertory.

Kind of work they did: Long-running repertory productions included A Musical About Star Wars, Danny and Sylvia:The Danny Kaye Musical, Tony ‘n’ Tina’s Wedding, My Big Gay Italian Wedding, My Big Gay Italian Funeral, Sistas: The Musical, Black Angels of Tuskegee and The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

Reason for closure: Gaynes announced St. Luke’s closure in January of 2021, blaming the city’s “forced lockdown” and saying the theatre had been shuttered “by government fiat.” The church staff then sought new leadership to reinvent the space, and it reopened as Playhouse 46 at St. Luke’s in April 2022 under the leadership of producer Jennifer Pluff with the new musical Islander.

Sundance Theatre Program

Utah/Wyoming/New York City, 1984-2022

Who they were: When Robert Redford’s film and media company took over the Utah Playwriting Conference, founded in 1980, it was renamed Sundacne Playwrights Lab. Led by David Kranes, it offered intensive script development for writers, who were invited to participate based on the recommendations of theatres. In 1997, Kranes stepped down and it was renamed the Theatre Lab, a sign of an expanded focus on all kinds of theatre (musicals, dance-theatre, performance art, etc.). Philip Himberg was named the producing director of the overall Theatre Program. A few years later, an invitation-only playwrights retreat began at the UCross Foundation in Wyoming, and the Lab itself sprang free from Utah, with iterations in New York City, Massachusetts, East Africa, and Morocco.

What kind of work they did: Among the works shepherded through Sundance’s unique development process were the musicals Passing Strange, Spring Awakening, The Light in the Piazza, Fun Home, and A Strange Loop, and the plays The Laramie Project, I Am My Own Wife, Yellowman, Dogeaters, Skeleton Crew, and Indecent.

Reason for closure: When Himberg stepped down in 2019, his colleague Christopher Hibma took over, and the Lab went virtual in 2020. Then Sundance announced “a break” to contemplate a “hybrid” model that would combine the Sundance Film Music Program and the Film’s New Frontiers Program with the vestiges of the Theatre Program. According to Himberg, that proposal was shelved in May 2022, and the entire theatre program with it.

Theatre22

Seattle, 2013-2022

Who they were: Founded by Corey McDaniel, who also served as the company’s producing artistic director, the company had a budget of approximately $80,300 as of 2021. From 2015 until the 2020 shutdown, Theatre22 staged their productions at 12th Avenue Arts.

Kind of work they did: Theatre22 produced a variety of contemporary works, including many by local Seattle playwrights like Wayne Rawley. At the time of their closing, the theatre had produced 16 mainstage shows. Their last production was the play Nonsense and Beauty by Scott C. Sickles, directed by McDaniel.

Reason for closure: Theatre22 announced their closure last August. They had only staged two indoor shows since the onset of COVID before facing the realization that they could not remain at their venue. According to the Seattle Times, Theatre22 signed a contract to rent space from a Seattle Public Theater (SPT) venue to produce two shows. McDaniel told the Times’s Dusty Somers that he did not do his “due diligence” to ensure that Theatre22 would be able to work with SPT after 2022, leaving the company to scramble for a potential new venue or fold.

Triad Stage

Greensboro, N.C., 2002-2023

Who they were: Triad Stage was founded in 2002 to bring live, professional theatre to a rejuvenated downtown Greensboro, the third most populous city in North Carolina. Co-founders Preston Lane and Richard Whittington purchased a vacant building and transformed it into a theatre center with a 300-seat live performance space (an 80-seat cabaret space was added in 2008).

Kind of work they did: Triad presented revivals and classics alongside occasional new works. Some new plays were by Southern writers, like Elyzabeth Gregory Wilder’s White Lightning, while others came to Triad following New York success, such as Jon Robin Baitz’s Other Desert Cities. Triad planned 2023-24 season was to include the world premiere of Jekyll by Patricia Lynn; Every Christmas Story Ever Told (And Then Some) by Michael Carleton, James FitzGerald, and John K. Alvarez; Chicken and Biscuits by Douglas Lyons; and Coal Country by Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen.

Reason for closure: When theatres closed in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Triad was already carrying an accumulated deficit of $1.5 million. During the shutdown, the theatre faced a reckoning around allegations of a toxic culture and seasons dominated by white artists, and Lane stepped down as artistic director in November 2020 after facing accusations of sexual misconduct. Triad shifted its artistic focus to include newer productions and more diverse storytelling, as well as a reduced operating budget, but was still unable to sustain operations following poor ticket sales.

Tricklock

Albuquerque, N.M., 1993-2020