Abstract

MUTYH plays an essential role in preventing oxidation-caused DNA damage. Pathogenic germline variations in MUTYH damage its function, causing intestinal polyposis and colorectal cancer. Determination of the evolutionary origin of the variation is essential to understanding the etiological relationship between MUTYH variation and cancer development. In this study, we analyzed the origins of pathogenic germline variants in human MUTYH. Using a phylogenic approach, we searched MUTYH pathogenic variants in modern humans in the MUTYH of 99 vertebrates across eight clades. We did not find pathogenic variants shared between modern humans and the non-human vertebrates following the evolutionary tree, ruling out the possibility of cross-species conservation as the origin of human pathogenic variants in MUTYH. We then searched the variants in the MUTYH of 5031 ancient humans and extinct Neanderthals and Denisovans. We identified 24 pathogenic variants in 42 ancient humans dated between 30,570 and 480 years before present (BP), and three pathogenic variants in Neanderthals dated between 65,000 and 38,310 years BP. Data from our study revealed that human MUTYH pathogenic variants mostly arose in recent human history and partially originated from Neanderthals.

Keywords: MUTYH, pathogenic variant, evolutionary origin, phylogenic, archaeological, ancient humans

1. Introduction

MUTYH plays a crucial role in preventing oxidation-caused DNA damage. Through glycosylating the mismatched adenine in the OG:A pair, MUTYH guides other components in the base excision repair (BER) pathway to repair the damage to maintain genome stability [1]. Pathogenic germline variations in MUTYH damage its function. The biallelic variation in MUTYH causes the development of MUTYH-associated polyposis (MAP) and colorectal cancer [2]; the monoallelic variation in MUTYH primes the carriers to develop colorectal cancer, although the risk is lower than for the biallelic germline variation [3].

MUTYH is evolutionarily conserved from bacteria to mammals, reflecting its essential role in maintaining genome stability [4]. Aside from the highly conserved core adenine excision and OG recognition domains [5], MUTYH in higher eukaryotes evolved multiple new functional domains, such as the MUTYH interdomain connector (IDC) domain to interact with other genes in multiple DNA damage repair (DDR) pathways [6,7]. Human MUTYH is under positive selection [8], suggesting that MUTYH variants can be beneficial [9], and that there must be rich variants in MUTYH. Indeed, 1838 germline variants in human MUTYH have been identified and deposited in the ClinVar database [10]. MUTYH variants can be deleterious—damaging its function—and 172 germline MUTYH variants have been determined as pathogenic, causing MAP and hereditary cancer-predisposing syndrome. For example, biallelic MUTYH variants c.527A > G (p.Tyr176Cys) and c.1178G > A (p.Gly393Asp) have been determined as MUTYH founder variants for MAP in European populations [11].

To better understand human diseases, particularly the pathogenic germline variation-related ones, it requires clarifying the evolutionary origin and the arising time of germline variations. The information will reveal how natural selection selects the deleterious variants, the relationship between adaptations and human diseases, and the heritage of deleterious variations within human population. However, the evolutionary origins of the deleterious variations in human MUTYH remain elusive.

In the current study, we explored the evolutionary origins of pathogenic variants in human MUTYH. While the conservation of human MUTYH sequences across different species suggests that human MUTYH pathogenic variants could have originated from common ancestors, the positive selection in human MUTYH suggests that human MUTYH pathogenic variants may have also arisen during the human evolution process. The rapid development of genomics has provided abundant genome sequences from various species, ancient humans, and the extinct Neanderthals and Denisovans [12]. Taking advantage of the rich genome resources, we conducted both phylogenic and archaeological studies to investigate the evolutionary origin of the human MUTYH pathogenic variants. Our study reveals that human MUTYH pathogenic variants mainly arose in recent human history and were partially inherited from Neanderthals.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Source of Human MUTYH Variants

Human MUTYH variants were downloaded from the ClinVar database [10]. Based on the classes, the variants were divided into the pathogenic variants (PVs) group including “Pathogenic,” “Likely Pathogenic” and “Pathogenic and Likely Pathogenic”; and the benign variants (BVs) group including “Benign,” “Likely Benign” and “Benign and Likely Benign”. Single-nucleotide variants and indels affecting <4 bases were included in the study.

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

The process followed the detailed procedures described in our previous publication [13]. Briefly, the reference sequences used in annotating human MUTYH variants were: hg38 NC_000001.11 for the genomic position, NM_012222 for cDNA and NP_036354 for protein. MUTYH genomic sequences included 100 species of vertebrates in eight clades: Primate, Euarchontoglires, Laurasiatheria, Afrotheria, Mammal, Aves, Sarcopterygii and Fish. Sequence alignment was performed following the procedures in Multiz Alignments in the UCSC genome browser [14]. The PhyloFit program in the PHAST package was used to build the tree model for the 100 vertebrate species [15]. PhastCons and phyloP in the PHAST package were used to measure evolutionary conservation. Lastz (BLASTZ) and Multiz were used to align repeat-masked sequences between human hg38 and non-human MUTYH genome sequences [16,17,18,19]. The scoring matrix and pairwise parameters for each species were adjusted by referring to the phylogenetic distances from the references. GetBase [20] was used to obtain the bases at the positions corresponding to human pathogenic and benign variants.

2.3. Archaeological Analysis

Ancient human genome information was collected from Allen Ancient DNA Resource [21], PubMed and Google scholar. Afterwards, BAM or SRA files of ancient human DNA sequences and related publications were downloaded from the European Nucleotide Archive [22], the Max Planck Institute Genome Projects [23] and the National Genomics Data Center [24]. The sequences containing MUTYH (chr1:45794835–45806142, hg19 and Chr1: 45567501–45578729, hg18 by Ensembl) were extracted using the sam-dump command in the official SRA toolkit, and base quality scores were rescaled using mapDamage 2.0 [25]. The MUTYH sequences were mapped to hg19 or hg18 reference sequences depending on the versions of the ancient DNA sequences. The Mpileup command in SAMtools [26] was used for variant calling from the mapped sequences with the minimal base quality of 1 [26]. After generating VCF files of ancient humans, the called variants were annotated with ANNOVAR [27] using the table_annovar.pl script containing the ClinVar, refGene and avsnp150. The variants from ancient DNA were compared with those from ClinVar to identify the shared and unshared variants between ancient and modern humans. For the shared variants, the locations and the fossil ages of the ancient carriers were identified from their original publications. The geographical distribution map of the ancient MUTYH pathogenic variants was created using Matlab software (The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). The following conditions were set to ensure the reliability of the variants identified in the ancient sequences: (1) MapDamage was used to remove false-positive variants caused by deamination of ancient DNA; (2) the called variants were manually checked for their reliability; (3) each variant must have a dbSNP ID to diminish sequencing artefacts.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Comparison of sharing rates between PV and BV groups was performed by Mann–Whitney U test using SPSS software version 24 (p < 0.05 as significant).

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic Analysis of Human MUTYH Variants in Non-Human Vertebrates

A total of 750 germline variants in human MUTYH consisting of 172 PVs and 578 BVs were included in the study (Table S1). The variants were searched in the 99 vertebrates in 8 clades of Primate, Euarchontoglires, Laurasiatheria, Afrotheria, Mammal, Aves, Sarcopterygii and Fish. The results were as follows:

3.1.1. PVs

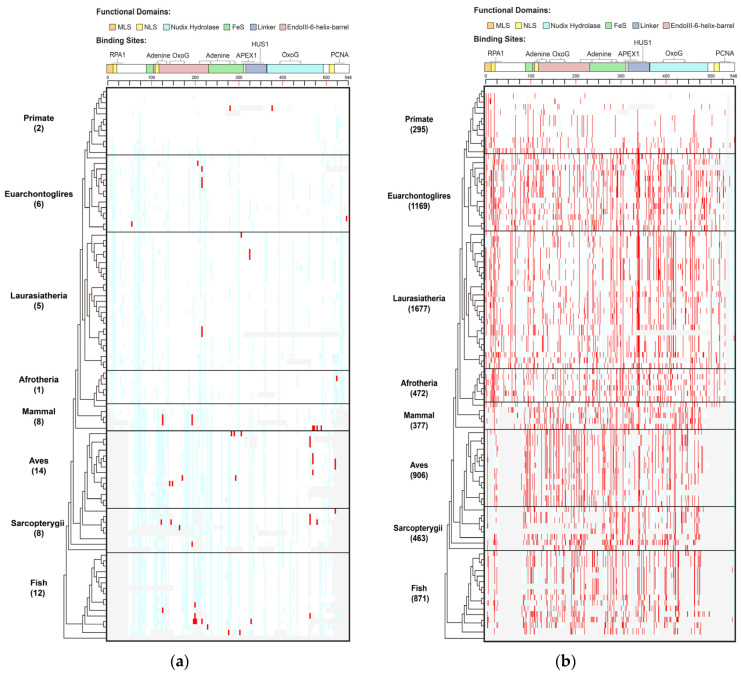

Thirty-three (19.2%) of the 172 human MUTYH PVs were identified in 36 species, of which stop-gain/nonsense variants, nonsynonymous SNV, splicing and frameshift deletion accounted for 48.5%, 21.2%, 15.2% and 12.1%, respectively (Figure 1, Table S2). We observed the following features of the shared variants.

Figure 1.

Distribution of human MUTYH variants in 100 vertebrates of 8 clades. (a) Human MUTYH PVs; (b) Human MUTYH BVs. White cell: same as human wild type; red cell: same as human variants; light blue cell: different from both human wild type and variants; gray cell: gaps or unaligned. X axis: the shared variants, Y axis: the 100 species from human in Primate to lamprey in Fish. The schematic diagram of MUTYH functional domains and binding sites is shown on top of the figures.

Species in Primate barely shared human PVs. Species in Primate are the closest relatives to humans. However, there were no human MUTYH PVs shared in the chimp, gorilla, gibbon, rhesus, crabeating macaque, baboon, green monkey, marmoset, squirrel monkey or bushbaby. There were two human PVs of c.760del (p.Val255Phefs) and c.499del (p.Glu166_Val167insTer) shared with orangutans. Mice and rats are the widely used animal models in biomedical studies, but they did not share any human MUTYH PVs. In contrast to Primate, the distant clade Aves had the highest number of shared PVs of 14, and Fish had the second highestof 12 (Table S2, Figure S1). c.931C > T (p.Gln311Ter) was the most shared, being found in six species, including the lesser Egyptian jerboa, Chinese hamster and golden hamster among Euarchontoglires; the black flying fox and megabat in Laurasiatheria; and zebrafish in Fish. The three haplotype-confirmed human MUTYH founder mutations of c.527A > G (p.Tyr176Cys) and c.1178G > A (p.Gly393Asp) in the European population [11] and c.924 + 3A > C in the Italian population [28] were absent in all non-human vertebrates.

Shared variants did not follow the evolutionary tree. Of the 33 shared PVs, 23 (69.7%) were shared with only 1 species. For the variants shared by multiple species, they did not follow the order of the evolutionary tree continuously from the closest to the most distant from humans (Table S2, Figure S2A). For example, the six species in three clades indicated above shared c.931C > T (p.Gln311Ter); the pig in Laurasiatheria and rock pigeon in Aves shared c.682 − 1G > A; the platypus in Mammal and painted turtle in Sarcopterygii shared c.323T > C (p.Leu108Pro); and the Tasmanian devil and wallaby in Mammal and stickleback in Fish shared c.1231C > T (p.Gln411Ter).

3.1.2. BVs

A total of 519 (90% of 578) of the human BVs were shared with 98 species across all 8 clades (Table S3, Figure 1B, Figures S1 and S2B), indicating MUTYH BVs had a distinct sharing pattern from PVs.

Primates shared a total of 295 human BVs. For example, chimps shared eight human BVs (5 intronic: c.36 + 325C > G, c.340 − 7T > C, c.495 + 35A > G, c.1468 − 40C > G, c.1510 − 14C > G; 3 exonic: c.999T > C (p.Thr333=), c.1347A > G (p.Thr449=), c.1422G > C (p.Thr474=)). Mice shared the most (100) human BVs. At the clade level, Laurasiatheria had the highest sharing numberof 1677 BVs. The Mann–Whitney U test showed that the sharing rates of human BVs and human PVs were significantly different (p < 0.05) (Figure S1).

The shared BVs followed the evolutionary tree. Ten BVs were shared by all 8 clades, 24 were shared by 7 clades and 47 were shared by 6 clades, although Primate had a lower sharing rate than other clades (Table S3, Figure 1B). All species but lamprey in Fish shared human BVs. Most of the sharing continuously followed the evolutionary order (Figure S2B).

The results from the phylogenetic analysis demonstrated that evolutionary conservation was part of the origin of human MUTYH BVs, but not the origin for human MUTYH PVs.

3.2. Archaeological Analysis of MUTYH Variants in Ancient Humans

Using the same set of human MUTYH variants used in the phylogenetic analysis, we tested whether human MUTYH variants could arise during human evolution. We searched the variants in 5031 ancient humans dated between 45,045 and 100 years BP, 26 Neanderthals dated between 120,000 and 38,310 years BP, and 4 Denisovans dated between 158,500 and 69,650 years BP.

3.2.1. PVs

A total of 24 human MUTYH PVs were identified in 42 ancient human individuals dated between 30,570 and 480 years BP. We observed the following features:

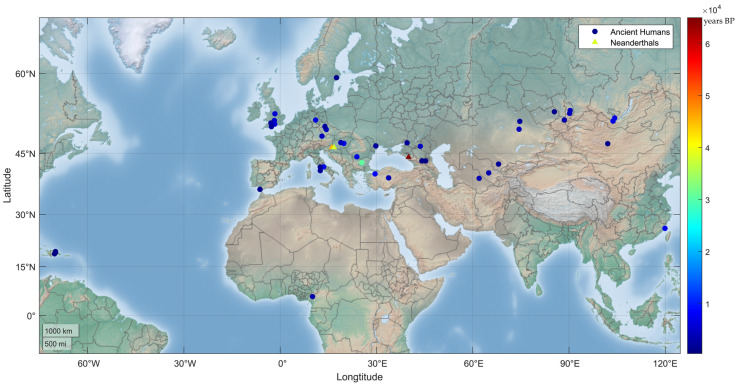

Most of the shared PVs arose recently. Except c.55C > T (p.Arg19Ter) in a carrier in Dryanovo, Bulgaria, dated to 30,570 years BP [29], 41 out of the 42 relevant ancient human individuals were dated to have lived within the last 10,000 years (Table 1, Figure 2); the youngest carrier for c.316C > T (p.Arg106Trp) in Atajadizo, Dominican Republic, was dated to 480 years BP [30].

Table 1.

List of MUTYH PVs shared in ancient individuals.

| Order | Years (BP) | Fossil Site | Variation | Type | dbSNP | Functional Domain [31] | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cDNA | Protein | |||||||

| A.Ancient Human | ||||||||

| 1 | 30,570 | Dryanovo, Bulgaria | c.55C > T | p.Arg19Ter | Stopgain | rs587780088 | NLS, RPA1 Binding site | [29] |

| 2 | 9100 | United Kingdom | c.724C > T | p.Arg242Cys | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs200495564 | FeS like | [32] |

| 3 | 8299 | Bartin, Turkey | c.1178G > A * | p.Gly393Asp | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs36053993 | Nudix like | [33] |

| 4 | 7628 | Grotta Continenza, Italy | c.527A > G * | p.Tyr176Cys | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs34612342 | EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [34] |

| 5 | 7500 | Matsu archipelago, China | c.280C > T | p.Arg94Ter | Stopgain | rs138775799 | FeS like, EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [35] |

| 6 | 7033 | Hungary | c.712C > T | p.Arg238Trp | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs34126013 | FeS like | [33] |

| 7 | 6713 | Irkutsk, Russia | c.535C > T | p.Arg179Cys | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs747993448 | EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [36] |

| 8 | 6700 | Irkutsk, Russia | c.1038G > A | p.Trp346Ter | Stopgain | rs1060501324 | Linker, HUS1 binding site | [36] |

| 9 | 6470 | Oltenia, Romania | c.169G > T | p.Glu57Ter | Stopgain | rs1557487793 | Not a domain | [37] |

| 10 | 6211 | Germany | c.1205C > T | p.Pro402Leu | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs529008617 | Nudix like | [38] |

| 11 | 5656 | United Kingdom | c.527A > G * | p.Tyr176Cys | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs34612342 | EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [32] |

| 12 | 5610 | United Kingdom | c.730C > T | p.Arg244Ter | Stopgain | rs587782885 | FeS like | [32] |

| 13 | 5455 | Gloucestershire, England | c.712C > T | p.Arg238Trp | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs34126013 | FeS like | [39] |

| 14 | 4649 | Russia | c.35G > A | p.Trp12Ter | Stopgain | rs1064795596 | MLS, RPA1 Binding site | [40] |

| 15 | 4249 | Germany | c.1003C > T | p.Gln335Ter | Stopgain | rs587780082 | Linker, HUS1 binding site | [40] |

| 16 | 4239 | Uybat, Russia | c.780G > A | p.Trp260Ter | Stopgain | rs1338038953 | MSH6 binding site | [36] |

| 17 | 4100 | Kazakhstan | c.1178G > A * | p.Gly393Asp | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs36053993 | Nudix like | [36] |

| 18 | 4078 | Verkhni Askiz, Russia | c.316C > T | p.Arg106Trp | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs765123255 | FeS like, EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [36] |

| 19 | 3850 | Czech Republic | c.535C > T | p.Arg179Cys | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs747993448 | EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [41] |

| 20 | 3774 | Hungary | c.1204C > T | p.Pro402Ser | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs121908382 | Nudix like | [42] |

| 21 | 3600 | Kaman, Turkey | c.35G > A | p.Trp12Ter | Stopgain | rs1064795596 | MLS, RPA1 Binding site | [36] |

| 22 | 3407 | Kazburun, Turkmenistan | c.1205C > T | p.Pro402Leu | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs529008617 | Nudix like | [43] |

| 23 | 3145 | Uzbekistan | c.1205C > T | p.Pro402Leu | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs529008617 | Nudix like | [44] |

| 24 | 3099 | Russia | c.712C > T | p.Arg238Trp | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs34126013 | FeS like | [40] |

| 25 | 3065 | Shum Laka, Cameroon | c.1255C > T | p.Gln419Ter | Stopgain | rs1437789978 | Nudix like | [42] |

| 26 | 2320 | Laos | c.724C > T | p.Arg242Cys | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs200495564 | FeS like | [45] |

| 27 | 2248 | United Kingdom | c.1429G > T | p.Glu477Ter | Stopgain | rs121908381 | Nudix like | [41] |

| 28 | 2234 | Glinoe, Moldova | c.725G > A | p.Arg242His | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs140342925 | FeS like | [43] |

| 29 | 2203 | Saryarka, Kazakhstan | c.712C > T | p.Arg238Trp | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs34126013 | FeS like | [46] |

| 30 | 2200 | United Kingdom | c.280C > T | p.Arg94Ter | Stopgain | rs138775799 | FeS like, EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [41] |

| 31 | 2185 | Czech Republic | c.1178G > A * | p.Gly393Asp | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs36053993 | Nudix like | [41] |

| 32 | 1933 | Rostov, Russia | c.1272G > A | p.Trp424Ter | Stopgain | rs1060501325 | Nudix like | [46] |

| 33 | 1850 | Via Paisiello, Italy | c.725G > A | p.Arg242His | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs140342925 | FeS like | [34] |

| 34 | 1850 | Via Paisiello, Italy | c.535C > T | p.Arg179Cys | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs747993448 | EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [34] |

| 35 | 1804 | South Kazakhstan | c.35G > A | p.Trp12Ter | Stopgain | rs1064795596 | MLS, RPA1 Binding site | [46] |

| 36 | 1236 | Arkhangai, Mongolia | c.536G > A | p.Arg179His | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs143353451 | EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [47] |

| 37 | 1208 | Russia | c.712C > T | p.Arg238Trp | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs34126013 | FeS like | [40] |

| 38 | 1125 | Cadiz, Spain | c.513G > A | p.Trp171Ter | Stopgain | rs1570423722 | EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [30] |

| 39 | 1050 | Birka, Sweden | c.85C > T | p.Gln29Ter | Stopgain | rs768386527 | RPA1 Binding site | [48] |

| 40 | 850 | Atajadizo, Dominican Republic | c.1205C > T | p.Pro402Leu | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs529008617 | Nudix like | [30] |

| 41 | 850 | North Ossetia | c.1204C > T | p.Pro402Ser | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs121908382 | Nudix like | [46] |

| 42 | 850 | North Ossetia | c.384G > A | p.Trp128Ter | Stopgain | rs587781295 | EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [46] |

| 43 | 480 | Atajadizo, Dominican Republic | c.316C > T | p.Arg106Trp | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs765123255 | FeS like, EndoIII-6-Helix-barrel like | [30] |

| B.Neanderthals | ||||||||

| 1 | 65,000 | Sukhoi Kurdzhips, Russia | c.848G > A | p.Gly283Glu | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs730881833 | FeS like, Adenine Binding site | [49] |

| 2 | 45,500 | Donja Voca, Croatia | c.1205C > T | p.Pro402Leu | Nonsynonymous SNV | rs529008617 | Nudix like | [49] |

| 3 | 38,310 | Donja Voca, Croatia | c.679C > T | p.Gln227Ter | Stopgain | rs1064796630 | EndoIII-6-helix-barrel like | [50] |

* Founder mutation; FeS: EndoIII-iron–sulfur cluster; MLS: mitochondrial localization signal; RPA1: replication protein A1; NLS: nuclear localization signal.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of human MUTYH PVs in ancient humans. A total of 24 human MUTYH PVs were identified in 42 ancient individuals, mostly from Europe and Asia, dated from 30,570 to 480 years BP. One of the 42 individuals had 2 PVs, and each of the other 41 individuals had 1 PV. Three PVs were also identified in the Neanderthals (triangle dots) of Croatia and Russia, dated between 65,000 and 38,310 years BP.

Stop-gain variants were common in the shared PVs. Of the 24 shared MUTYH PVs, 14 (58.3%) were stop-gain variants.

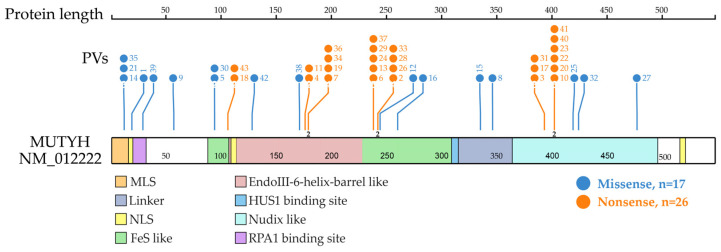

Shared PVs were located in different domains. The top three clustered domains were EndoIII-iron–sulfur cluster (FeS)-like domain, EndoIII-6-Helix_barrel domain and Nudix-like domain (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of MUTYH PVs shared in ancient individuals. It shows 21 codon positions of the 24 MUTYH PVs detected in 42 ancient individuals, of which 23 were located at functional domains. Each line represents one codon position with the PV number at the top (same order as in Table 1 dating from the oldest to the newest). Each codon position had one variant, except for 3 positions that had 2 variants represented by the number “2” at the bottom of the line. The top 3 clustered functional domains were EndoIII-iron–sulfur cluster (FeS)-like (15 PVs), EndoIII-6-Helix_barrel (12 PVs) and Nudix-like (12 PVs). Other domains included replication protein A1 (RPA1) binding site (5 PVs), mitochondrial localization signal (MLS) (3 PVs), HUS1 binding site (2 PVs), linker (2 PVs) and nuclear localization signal (NLS) (1 PV).

The shared PVs were highly reliable. Of the 24 shared MUTYH PVs, 11 were present in multiple individuals including 6 PVs in 2 individuals, 3 PVs in 3 individuals, 1 PV in 4 individuals and 1 PV in 5 individuals (Table 2). The presence of dbSNP ID for each variant further enhanced the reliability of the shared PVs.

Table 2.

Summary of MUTYH variants shared in ancient individuals.

| Category | Ancient Samples (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient humans | Neanderthals | Denisovans | |

| PVs | |||

| Types of variants | |||

| Stopgain | 14 (58.3) | 1 (33.3) | - |

| Nonsynonymous SNV | 10 (41.7) | 2 (66.7) | - |

| Total variants | 24 (100) | 3 (100) | - |

| Variants shared by | |||

| 1 carrier | 13 (54.2) | 3 (100) | - |

| 2 carriers | 6 (25.0) | - | - |

| 3 carriers | 3 (12.5) | - | - |

| 4 carriers | 1 (4.2) | - | - |

| 5 carriers | 1 (4.2) | - | - |

| Total variants | 24 (100) | 3 (100) | - |

| Total carriers | 42 | 3 | - |

| BVs | |||

| Types of variants | |||

| Synonymous SNV | 72 (57.1) | 12 (38.7) | 4 (57.1) |

| Intronic SNV | 44 (34.9) | 15 (48.4) | 1 (14.3) |

| Nonsynonymous SNV | 4 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | - |

| UTR | 4 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (28.6) |

| Deletion | 1 (0.8) | - | - |

| Total variants | 126 (100) | 31 (100) | 7 (100) |

| Variants shared by | |||

| 1 carrier | 76 (60.3) | 19 (61.3) | 7 (100) |

| 2 carriers | 22 (17.5) | 4 (12.9) | - |

| 3 carriers | 10 (7.9) | 1 (3.2) | - |

| 4 carriers | 2 (1.6) | 1 (3.2) | - |

| 5 carriers | 2 (1.6) | 1 (3.2) | - |

| 7 carriers | 1 (0.8) | 1 (3.2) | - |

| 11 carriers | 1 (0.8) | 1 (3.2) | - |

| 12 carriers | 1 (0.8) | 1 (3.2) | - |

| 14 carriers | 1 (0.8) | 1 (3.2) | - |

| 17 carriers | 1 (0.8) | 1 (3.2) | - |

| 21 carriers | 1 (0.8) | - | - |

| 29 carriers | 1 (0.8) | - | - |

| 163 carriers | 1 (0.8) | - | - |

| 166 carriers | 1 (0.8) | - | - |

| 183 carriers | 1 (0.8) | - | - |

| 276 carriers | 1 (0.8) | - | - |

| 382 carriers | 1 (0.8) | - | - |

| 516 carriers | 1 (0.8) | - | - |

| 1821 carriers | 1 (0.8) | - | - |

| Total variants | 126 (100) | 31 (100) | 7 (100) |

| Total carriers | 2217 | 18 | 1 |

Founder variants were shared. The 24 shared PVs included two MUTYH founder variants of c.527A > G (p.Tyr176Cys) and c.1178G > A (p.Gly393Asp) in the European population [11]. c.536A > G (p.Tyr179Cys) was present in two individuals: one individual dated to 7701 years BP from Italy and the other dated to 5730 years BP from England; c.1187G > A (p.Gly396Asp) was present in three individuals: one dated to 8315 years BP from Turkey, one dated to 3713 years BP from Kazakhstan and another dated to 2185 years BP from Czech Republic.

Neanderthals shared MUTYH PVs with modern humans. Three MUTYH PVs were identified in three Neanderthals dated from 65,000 to 38,310 years BP. c.1205C > T (p.Pro402Leu) identified in Neanderthals was also detected in ancient humans. No human MUTYH PV was detected in Denisovans (Table 1 and Table 2).

3.2.2. BVs

A total of 126 human MUTYH BVs (Table S4a) were identified in 2217 ancient humans dated from 37,470 to 135 years BP. These shared BVs had the following features:

MUTYH BVs were highly shared between ancient and modern humans. Twenty-two (17.5%) were present in 2 ancient individuals, 10 (7.9%) were present in 3 individuals and 18 (14.3%) were present in multiple individuals. c.495 + 35A > G had the highest sharing within 1821 carriers, and c.1468 − 40C > G had the second highest sharing within 516 carriers (Table S4a).

Most BVs arose recently. Except for c.1468 − 40C > G in a carrier in Russia dated to 37,470 years BP [51], most of the shared BVs arose within the last 10,000 years. c.495 + 35A > G was the youngest one identified in a carrier in Efate, Vanuatu, dated to 135 years BP [52].

Shared BVs were mostly synonymous (72, 57.1%) and intronic (44, 34.9%).

Neanderthals and Denisovans shared MUTYH BVs with modern humans. A total of 31 BVs were identified in the Neanderthals, and 7 were identified in Denisovans. Of these 38 BVs, 32 were synonymous and intronic (Table 2, Table S4a). c.1468 − 40C > G was shared by ancient humans, Neanderthals and Denisovans; 18 BVs were shared by two groups, of which 1 was shared between Denisovans and Ancient humans; and 17 were shared between Neanderthals and ancient humans (Table S4b).

The results from the phylogenical and archaeological analysis showed that human MUTYH PVs mostly originated from ancient humans and partly from the extinct Neanderthals. In contrast, human MUTYH BVs mostly originated from non-human vertebrates or humans and partly from the extinct Neanderthals and Denisovans.

4. Discussion

By referring to the rich genomic data from non-human vertebrate species and ancient humans, our study reveals that human MUTYH PVs mostly originated during recent human history.

Data from our phylogenetic study in non-human vertebrates do not support cross-species evolutionary conservation as the source for human MUTYH PVs. This is reflected by the fact that almost no human PVs were shared in the Primate clade. For the non-human species sharing human MUTYH PVs, they were mostly the species in Aves and Fish clades distant from humans. While these shared PVs could likely be generated by chance in humans and these shared species, the cause for the sharing of genetic variants with distant species remains unclear. Different theories have been proposed in trying to explain the situation, such as the “founder effect,” “fixations of slightly deleterious mutations,” “relaxed selection on late-onset phenotypes” and “compensatory changes” [53]. The “compensatory changes” theory is considered a favorable explanation for the sharing of human PVs with distant species. It considers that “compensatory mutations at other sites of the same or a different protein render the deleterious mutations neutral”. In comparison, human MUTYH BVs shared with other vertebrates followed the order of the evolutionary tree, which served as a convincing control for PVs’ sharing pattern, which did not follow the order of the evolutionary tree.

Our anthropological analysis of ancient humans identified 42 ancient carriers for 24 human MUTYH PVs, including two founder variants. Forty-one out of the 42 ancient carriers were dated between 9100 and 480 years BP, highlighting that human MUTYH PVs likely originated during recent human history after the last glacier period of the Quaternary that ended approximately 11,000 years BP. Pathogenic variants are deleterious for fitness. Therefore, evolutionary selection should suppress their presence in the human population. However, multiple MUTYH PVs were present at rather high levels, suggesting their potential benefitial effects. While we do not have enough evidence to support this possibility, we speculate that the pathogenic effects could be developmental stage-dependent: the pathogenic variants could be beneficial at the reproductive stage but deleterious at later reproduction stages. Cancer caused by the pathogenic variants occurs mostly at the later reproduction stage. Before reaching the stage, however, the PVs have already been transmitted to the next generation. The abundance of BVs shared across many species indicates the beneficial or neutral effects. Only 24 out of the 172 MUTYH PVs were identified in ancient humans The incidence of 0.85% implies that 1 out of 117 ancient individuals carried one MUTYH germline pathogenic variant, which is lower than the carrier frequency in modern humans estimated to be around 1:45 [54]. We speculate that the origination of MUTYH PVs has been gradually increasing following the expansion of the human population.

It is interesting to note that most of the MUTYH PVs were present in modern humans but not in ancient humans since only 24 out of the 172 MUTYH PVs were identified in ancient humans. The following factors could contribute to the fact: (1) Different sizes of ancient and modern human populations. In this study, only 24 out of the 172 MUTYH PVs from modern humans were identified in ancient humans. It was estimated that there were only a few hundred to a few thousand individuals when human migrated out of Africa. Afterwards, the size of the human population gradually increased but rapidly expanded after the last glacier period (11,000 years BP), and further increased after agricultural development (7000–5000 years BP) till nowadays. The probability of new variants arising in a larger population, therefore, increased. (2) The limited number of ancient samples. Although a significant progress in anthropological genomics has been made, genomic sequence data from ancient humans remain limited that they are only available from about 5000 ancient individuals. With data from more ancient samples, it would be expected that more PVs found in modern humans could be identified in ancient humans. (3) Different lifespans for modern and ancient humans. Modern humans have much greater longevity than ancient humans did. Cancer is an aging disease. With prolonged lifespans, cancer incidence in the modern human population is increasing as shown by epidemiological data. Although evidence indeed revealed the presence of cancer in ancient humans, only a few PVs were detected in ancient individuals.

Anthropological genomic studies found that parts of the modern human genome were inherited from Neanderthals and Denisovans [55,56,57], and some alleles were related to human diseases, such as a risk for depression and skin lesions [58]. Consistent with that observation, our study identified multiple MUTYH PVs and BVs in Neanderthals and Denisovans, highlighting that the extinct Neanderthals and Denisovans also contributed disease susceptibility, including cancer, to modern humans.

Our findings are consistent with the observation that most deleterious protein-coding single nucleotide variants (SNVs) arose in the past few thousand years [59]. Through direct comparison of variants between modern humans and vertebrates and ancient humans, our study provide further evidence to support the concept that pathogenic variants in human disease-related genes could largely arise in recent human history.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful for the High-Performance Computing Cluster resource and facilities provided by the Information and Communication Technology Office, University of Macau. We were also thankful for the English editing of this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biom13030429/s1. Figure S1: Quantitative distribution of human MUTYH PVs and BVs in 100 vertebrates. Figure S2: Distribution of different groups of human germline MUTYH variants in eight clades. Table S1: Human MUTYH variants used in the study. Table S2: Distribution of human germline MUTYH PVs in other species. Table S3: Distribution of human germline MUTYH BVs in other species. Table S4: List of MUTYH BVs in ancient individuals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M.W., F.X. and J.L.; Methodology, F.X. and J.L.; Data Curation, F.X., S.H.K., H.L., J.L. and P.N.P.L.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, F.X.; Writing—Review and Editing, S.M.W., P.N.P.L., S.H.K., H.L. and B.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study, which can be found through references [10,14,21,22,23,24].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Macau Science and Technology Development Fund (No. 085/2017/A2, 0077/2019/AMJ, 0032/2022/A1), the University of Macau Fund (No. SRG2017-00097-FHS, MYRG2019-00018-FHS, 2020-00094-FHS) and the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau (No. FHSIG/SW/0007/2020P, MOE Frontiers Science Center for Precision Oncology pilot grant, and a startup fund) to S.M.W.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.David S.S., O’Shea V.L., Kundu S. Base-Excision Repair of Oxidative DNA Damage. Nature. 2007;447:941–950. doi: 10.1038/nature05978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazzei F., Viel A., Bignami M. Role of MUTYH in Human Cancer. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2013;743–744:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedics G., Kotmayer L., Zajta E., Hegyi L.L., Brückner E.Á., Rajnai H., Reiniger L., Bödör C., Garami M., Scheich B. Germline MUTYH Mutations and High-Grade Gliomas: Novel Evidence for a Potential Association. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2022;61:622–628. doi: 10.1002/gcc.23054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Slupska M.M., Baikalov C., Luther W.M., Chiang J.H., Wei Y.F., Miller J.H. Cloning and Sequencing a Human Homolog (HMYH) of the Escherichia Coli MutY Gene Whose Function Is Required for the Repair of Oxidative DNA Damage. J. Bacteriol. 1996;178:3885–3892. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.13.3885-3892.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banda D.M., Nuñez N.N., Burnside M.A., Bradshaw K.M., David S.S. Repair of 8-OxoG:A Mismatches by the MUTYH Glycosylase: Mechanism, Metals and Medicine. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017;107:202–215. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luncsford P.J., Manvilla B.A., Patterson D.N., Malik S.S., Jin J., Hwang B.-J., Gunther R., Kalvakolanu S., Lipinski L.J., Yuan W., et al. Coordination of MYH DNA Glycosylase and APE1 Endonuclease Activities via Physical Interactions. DNA Repair. 2013;12:1043–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2013.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raetz A.G., David S.S. When You’re Strange: Unusual Features of the MUTYH Glycosylase and Implications in Cancer. DNA Repair. 2019;80:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgan C.C., Shakya K., Webb A., Walsh T.A., Lynch M., Loscher C.E., Ruskin H.J., O’Connell M.J. Colon Cancer Associated Genes Exhibit Signatures of Positive Selection at Functionally Significant Positions. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012;12:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pope M.A., David S.S. DNA Damage Recognition and Repair by the Murine MutY Homologue. DNA Repair. 2005;4:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.ClinVar Database. [(accessed on 19 May 2022)]; Available online: https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/clinvar/

- 11.Aretz S., Tricarico R., Papi L., Spier I., Pin E., Horpaopan S., Cordisco E.L., Pedroni M., Stienen D., Gentile A., et al. MUTYH-Associated Polyposis (MAP): Evidence for the Origin of the Common European Mutations p.Tyr179Cys and p.Gly396Asp by Founder Events. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;22:923–929. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orlando L., Allaby R., Skoglund P., der Sarkissian C., Stockhammer P.W., Ávila-Arcos M.C., Fu Q., Krause J., Willerslev E., Stone A.C., et al. Ancient DNA Analysis. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 2021;1:14. doi: 10.1038/s43586-020-00011-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J., Zhao B., Huang T., Qin Z., Wang S.M. Human BRCA Pathogenic Variants Were Originated during Recent Human History. Life Sci. Alliance. 2022;5:e202101263. doi: 10.26508/lsa.202101263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Multiz Alignments of 100 Vertebrates. [(accessed on 20 May 2022)]. Available online: https://genome.ucsc.edu/cgi-bin/hgc?db=hg38&c=chr17&l=43106526&r=43106527&o=43106526&t=43106527&g=multiz100way&i=multiz100way.

- 15.Murphy W.J., Eizirik E., O’Brien S.J., Madsen O., Scally M., Douady C.J., Teeling E., Ryder O.A., Stanhope M.J., de Jong W.W., et al. Resolution of the Early Placental Mammal Radiation Using Bayesian Phylogenetics. Science. 2001;294:2348–2351. doi: 10.1126/science.1067179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanchette M., Kent W.J., Riemer C., Elnitski L., Smit A.F.A., Roskin K.M., Baertsch R., Rosenbloom K., Clawson H., Green E.D., et al. Aligning Multiple Genomic Sequences with the Threaded Blockset Aligner. Genome Res. 2004;14:708–715. doi: 10.1101/gr.1933104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hubisz M.J., Pollard K.S., Siepel A. PHAST and RPHAST: Phylogenetic Analysis with Space/Time Models. Brief. Bioinform. 2011;12:41–51. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbq072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Armstrong J., Fiddes I.T., Diekhans M., Paten B. Whole-Genome Alignment and Comparative Annotation. Annu. Rev. Anim. Biosci. 2019;7:41–64. doi: 10.1146/annurev-animal-020518-115005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramani R., Krumholz K., Huang Y.-F., Siepel A. PhastWeb: A Web Interface for Evolutionary Conservation Scoring of Multiple Sequence Alignments Using PhastCons and PhyloP. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:2320–2322. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.GetBase. [(accessed on 2 June 2022)]. Available online: https://github.com/Skylette14/GetBase.

- 21.Allen Ancient DNA Resource. [(accessed on 10 October 2021)]. Available online: https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/allen-ancient-dna-resource-aadr-downloadable-genotypes-present-day-and-ancient-dna-data.

- 22.European Nucleotide Archive. [(accessed on 2 March 2022)]. Available online: https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/home.

- 23.Max Planck Institute Genome Project. [(accessed on 1 June 2022)]. Available online: https://www.eva.mpg.de/genetics/genome-projects/

- 24.National Genomics Data Center. [(accessed on 2 March 2022)]. Available online: https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/databases.

- 25.Jónsson H., Ginolhac A., Schubert M., Johnson P.L.F., Orlando L. MapDamage2.0: Fast Approximate Bayesian Estimates of Ancient DNA Damage Parameters. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:1682–1684. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H., Handsaker B., Wysoker A., Fennell T., Ruan J., Homer N., Marth G., Abecasis G., Durbin R. The Sequence Alignment/Map Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang K., Li M., Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: Functional Annotation of Genetic Variants from High-Throughput Sequencing Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pin E., Pastrello C., Tricarico R., Papi L., Quaia M., Fornasarig M., Carnevali I., Oliani C., Fornasin A., Agostini M., et al. MUTYH c.933+3A&C, Associated with a Severely Impaired Gene Expression, Is the First Italian Founder Mutation in MUTYH-Associated Polyposis. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;132:1060–1069. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hajdinjak M., Mafessoni F., Skov L., Vernot B., Hübner A., Fu Q., Essel E., Nagel S., Nickel B., Richter J., et al. Initial Upper Palaeolithic Humans in Europe Had Recent Neanderthal Ancestry. Nature. 2021;592:253–257. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03335-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandes D.M., Sirak K.A., Ringbauer H., Sedig J., Rohland N., Cheronet O., Mah M., Mallick S., Olalde I., Culleton B.J., et al. A Genetic History of the Pre-Contact Caribbean. Nature. 2021;590:103–110. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03053-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Out A.A., Tops C.M.J., Nielsen M., Weiss M.M., van Minderhout I.J.H.M., Fokkema I.F.A.C., Buisine M.-P., Claes K., Colas C., Fodde R., et al. Leiden Open Variation Database of the MUTYH Gene. Hum. Mutat. 2010;31:1205–1215. doi: 10.1002/humu.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brace S., Diekmann Y., Booth T.J., van Dorp L., Faltyskova Z., Rohland N., Mallick S., Olalde I., Ferry M., Michel M., et al. Ancient Genomes Indicate Population Replacement in Early Neolithic Britain. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019;3:765–771. doi: 10.1038/s41559-019-0871-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathieson I., Lazaridis I., Rohland N., Mallick S., Patterson N., Roodenberg S.A., Harney E., Stewardson K., Fernandes D., Novak M., et al. Genome-Wide Patterns of Selection in 230 Ancient Eurasians. Nature. 2015;528:499–503. doi: 10.1038/nature16152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antonio M.L., Gao Z., Moots H.M., Lucci M., Candilio F., Sawyer S., Oberreiter V., Calderon D., Devitofranceschi K., Aikens R.C., et al. Ancient Rome: A Genetic Crossroads of Europe and the Mediterranean. Science. 2019;366:708–714. doi: 10.1126/science.aay6826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Larena M., Sanchez-Quinto F., Sjödin P., McKenna J., Ebeo C., Reyes R., Casel O., Huang J.-Y., Hagada K.P., Guilay D., et al. Multiple Migrations to the Philippines during the Last 50,000 Years. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:e2026132118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2026132118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Barros Damgaard P., Martiniano R., Kamm J., Moreno-Mayar J.V., Kroonen G., Peyrot M., Barjamovic G., Rasmussen S., Zacho C., Baimukhanov N., et al. The First Horse Herders and the Impact of Early Bronze Age Steppe Expansions into Asia. Science. 2018;360:aar7711. doi: 10.1126/science.aar7711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathieson I., Alpaslan-Roodenberg S., Posth C., Szécsényi-Nagy A., Rohland N., Mallick S., Olalde I., Broomandkhoshbacht N., Candilio F., Cheronet O., et al. The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe. Nature. 2018;555:197–203. doi: 10.1038/nature25778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipson M., Szécsényi-Nagy A., Mallick S., Pósa A., Stégmár B., Keerl V., Rohland N., Stewardson K., Ferry M., Michel M., et al. Parallel Palaeogenomic Transects Reveal Complex Genetic History of Early European Farmers. Nature. 2017;551:368–372. doi: 10.1038/nature24476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fowler C., Olalde I., Cummings V., Armit I., Büster L., Cuthbert S., Rohland N., Cheronet O., Pinhasi R., Reich D. A High-Resolution Picture of Kinship Practices in an Early Neolithic Tomb. Nature. 2022;601:584–587. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04241-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allentoft M.E., Sikora M., Sjögren K.-G., Rasmussen S., Rasmussen M., Stenderup J., Damgaard P.B., Schroeder H., Ahlström T., Vinner L., et al. Population Genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia. Nature. 2015;522:167–172. doi: 10.1038/nature14507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patterson N., Isakov M., Booth T., Büster L., Fischer C.-E., Olalde I., Ringbauer H., Akbari A., Cheronet O., Bleasdale M., et al. Large-Scale Migration into Britain during the Middle to Late Bronze Age. Nature. 2022;601:588–594. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04287-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lipson M., Ribot I., Mallick S., Rohland N., Olalde I., Adamski N., Broomandkhoshbacht N., Lawson A.M., López S., Oppenheimer J., et al. Ancient West African Foragers in the Context of African Population History. Nature. 2020;577:665–670. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-1929-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krzewińska M., Kılınç G.M., Juras A., Koptekin D., Chyleński M., Nikitin A.G., Shcherbakov N., Shuteleva I., Leonova T., Kraeva L., et al. Ancient Genomes Suggest the Eastern Pontic-Caspian Steppe as the Source of Western Iron Age Nomads. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:aat4457. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aat4457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narasimhan V.M., Patterson N., Moorjani P., Rohland N., Bernardos R., Mallick S., Lazaridis I., Nakatsuka N., Olalde I., Lipson M., et al. The Formation of Human Populations in South and Central Asia. Science. 2019;365:aat7487. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gakuhari T., Nakagome S., Rasmussen S., Allentoft M.E., Sato T., Korneliussen T., Chuinneagáin B.N., Matsumae H., Koganebuchi K., Schmidt R., et al. Ancient Jomon Genome Sequence Analysis Sheds Light on Migration Patterns of Early East Asian Populations. Commun. Biol. 2020;3:437. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-01162-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Damgaard P.d.B., Marchi N., Rasmussen S., Peyrot M., Renaud G., Korneliussen T., Moreno-Mayar J.V., Pedersen M.W., Goldberg A., Usmanova E., et al. 137 Ancient Human Genomes from across the Eurasian Steppes. Nature. 2018;557:369–374. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeong C., Wang K., Wilkin S., Taylor W.T.T., Miller B.K., Bemmann J.H., Stahl R., Chiovelli C., Knolle F., Ulziibayar S., et al. A Dynamic 6,000-Year Genetic History of Eurasia’s Eastern Steppe. Cell. 2020;183:890–904. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hedenstierna-Jonson C., Kjellström A., Zachrisson T., Krzewińska M., Sobrado V., Price N., Günther T., Jakobsson M., Götherström A., Storå J. A Female Viking Warrior Confirmed by Genomics. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 2017;164:853–860. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.23308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hajdinjak M., Fu Q., Hübner A., Petr M., Mafessoni F., Grote S., Skoglund P., Narasimham V., Rougier H., Crevecoeur I., et al. Reconstructing the Genetic History of Late Neanderthals. Nature. 2018;555:652–656. doi: 10.1038/nature26151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Green R.E., Krause J., Briggs A.W., Maricic T., Stenzel U., Kircher M., Patterson N., Li H., Zhai W., Fritz M.H.-Y., et al. A Draft Sequence of the Neandertal Genome. Science. 2010;328:710–722. doi: 10.1126/science.1188021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fu Q., Posth C., Hajdinjak M., Petr M., Mallick S., Fernandes D., Furtwängler A., Haak W., Meyer M., Mittnik A., et al. The Genetic History of Ice Age Europe. Nature. 2016;534:200–205. doi: 10.1038/nature17993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lipson M., Skoglund P., Spriggs M., Valentin F., Bedford S., Shing R., Buckley H., Phillip I., Ward G.K., Mallick S., et al. Population Turnover in Remote Oceania Shortly after Initial Settlement. Curr. Biol. 2018;28:1157–1165.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao L., Zhang J. Why Are Some Human Disease-Associated Mutations Fixed in Mice? Trends Genet. 2003;19:678–681. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Win A.K., Jenkins M.A., Dowty J.G., Antoniou A.C., Lee A., Giles G.G., Buchanan D.D., Clendenning M., Rosty C., Ahnen D.J., et al. Prevalence and penetrance of major genes and polygenes for colorectal cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2017;26:404–412. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Villanea F.A., Schraiber J.G. Multiple Episodes of Interbreeding between Neanderthal and Modern Humans. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2019;3:39–44. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0735-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wall J.D., Yoshihara Caldeira Brandt D. Archaic Admixture in Human History. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2016;41:93–97. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2016.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reich D., Green R.E., Kircher M., Krause J., Patterson N., Durand E.Y., Viola B., Briggs A.W., Stenzel U., Johnson P.L.F., et al. Genetic History of an Archaic Hominin Group from Denisova Cave in Siberia. Nature. 2010;468:1053–1060. doi: 10.1038/nature09710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simonti C.N., Vernot B., Bastarache L., Bottinger E., Carrell D.S., Chisholm R.L., Crosslin D.R., Hebbring S.J., Jarvik G.P., Kullo I.J., et al. The Phenotypic Legacy of Admixture between Modern Humans and Neandertals. Science. 2016;351:737–741. doi: 10.1126/science.aad2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fu W., O’Connor T.D., Jun G., Kang H.M., Abecasis G., Leal S.M., Gabriel S., Rieder M.J., Altshuler D., Shendure J., et al. Analysis of 6,515 Exomes Reveals the Recent Origin of Most Human Protein-Coding Variants. Nature. 2013;493:216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature11690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study, which can be found through references [10,14,21,22,23,24].