Abstract

Introduction:

Smoking prevalence in homeless populations is strikingly high (∼70%); yet, little is known about effective smoking cessation interventions for this population. We conducted a community-based clinical trial, Power To Quit (PTQ), to assess the effects of motivational interviewing (MI) and nicotine patch (nicotine replacement therapy [NRT]) on smoking cessation among homeless smokers. This paper describes the smoking characteristics and comorbidities of smokers in the study.

Methods:

Four hundred and thirty homeless adult smokers were randomized to either the intervention arm (NRT + MI) or the control arm (NRT + Brief Advice). Baseline assessment included demographic information, shelter status, smoking history, motivation to quit smoking, alcohol/other substance abuse, and psychiatric comorbidities.

Results:

Of the 849 individuals who completed the eligibility survey, 578 (68.1%) were eligible and 430 (74.4% of eligibles) were enrolled. Participants were predominantly Black, male, and had mean age of 44.4 years (S D = 9.9), and the majority were unemployed (90.5%). Most participants reported sleeping in emergency shelters; nearly half had been homeless for more than a year. Nearly all the participants were daily smokers who smoked an average of 20 cigarettes/day. Nearly 40% had patient health questionnaire-9 depression scores in the moderate or worse range, and more than 80% screened positive for lifetime history of drug abuse or dependence.

Conclusions:

This study demonstrates the feasibility of enrolling a diverse sample of homeless smokers into a smoking cessation clinical trial. The uniqueness of the study sample enables investigators to examine the influence of nicotine dependence as well as psychiatric and substance abuse comorbidities on smoking cessation outcomes.

Introduction

Despite progress in reducing cigarette smoking in the general U.S. population, smoking rates and related morbidity remain strikingly high among poor and underserved groups. One underserved group generally unreached by smoking cessation interventions is the 3 million persons annually experiencing homelessness in the United States. The cigarette smoking rate among the homeless remains an alarming 70% or greater (Wilder Foundation, 2004). The leading causes of death among homeless persons are heart disease and cancer, both of which are tobacco related (Hwang, 2000; Hwang, Orav, O’Connell, Lebow, & Brennan, 1997). Because smoking cessation research usually excludes people without a regular place of residence, there is lack of evidence-based information about how to help homeless smokers quit smoking. Despite ample evidence that pharmacotherapy and counseling are effective for smoking cessation in the general population, to date, little is known about effective methods for smoking cessation among homeless populations.

Because homeless individuals are faced with meeting basic survival needs such as finding food and shelter, many people may assume that smoking cessation is not a priority for the homeless and therefore ignore smoking as a health problem among the homeless. However, findings from the few studies conducted in homeless populations do not support this assumption. A survey of 236 homeless adults from nine homeless service sites found a smoking prevalence rate of 69%. Of the smokers, 37% reported readiness to quit smoking within the next 6 months (Connor, Cook, Herbert, Neal, & Williams, 2002) and 72% had tried to quit at least once in the past year. The same study found that nicotine replacement alone or in combination with other treatments was the most preferred treatment (42.2%). Thus, there appears to be considerable interest in smoking cessation aided with medication among homeless smokers.

Homeless smokers face multiple barriers to accessing and adhering to treatments (Teeter, 1999). Furthermore, high rates of psychiatric and other substance abuse comorbid conditions (el-Guebaly, Cathcart, Currie, Brown, & Gloster, 2002) within homeless populations create additional challenges to cessation for homeless smokers. Adherence to smoking cessation treatment under these circumstances can be challenging. Within the general population, those who do adhere to recommended treatment usually achieve better cessation outcomes (Lam, Abdullah, Chan, & Hedley, 2005; Shiffman et al., 2002). To date, there are no controlled trials among homeless persons of interventions to improve adherence to self-administered medications, such as nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). Considering the presence of numerous barriers to medication adherence in homeless populations, problems with adherence to NRT are likely to be of a greater magnitude than in housed populations. This expectation is supported by results from a pilot study (Okuyemi et al., 2006) in which only 32% (9/28) of the participants reported using four or more patches per week (out of recommended and study-provided seven patches/week) at their 8 weeks follow-up assessment. Those who reported using four or more patches a week had a 33.3% quit rate at Week 26 compared with 10.5% for those who used fewer than four patches per week. These data suggest that increasing NRT adherence may increase smoking cessation among homeless smokers.

To address the gap in effectiveness of evidence-based smoking cessation interventions in the homeless population, we conducted a community-based randomized study called Power To Quit (PTQ). The PTQ study assessed the effects of motivational interviewing (MI) counseling designed to improve adherence to nicotine patch (NRT) and smoking cessation outcomes among homeless smokers. The goal of the current paper is to describe the baseline smoking characteristics and comorbid conditions of homeless smokers enrolled in the PTQ study. Knowing the smoking characteristics as well as comorbid conditions of homeless adults who engage in a smoking cessation treatment study can inform the development of targeted smoking cessation interventions for homeless and other vulnerable populations.

Methods

All study procedures were approved and monitored by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Minnesota Medical School.

Design, Setting, and Participants

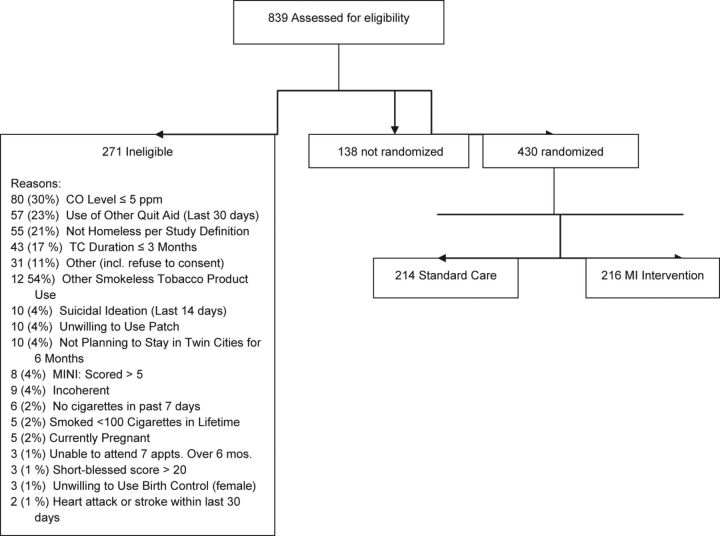

Study design and recruitment procedures have been described in detail in a separate manuscript (Goldade et al., 2011). Figure 1 shows an overview of study procedures. Participant recruitment began in May 2009 and ended in September 2010. The final Week 26 follow-up assessment was completed in April 2011. This study utilized a randomized, 2-group design with 26 weeks follow-up. Once deemed eligible, participants were randomized to either the intervention arm (NRT + MI) or the Standard Care (SC) control arm (NRT + Brief Advice). Eligibility criteria included that the participants were homeless (United States, 2004), a current cigarette smoker, aged 18 years or older, willing to use nicotine patches for 8 weeks and participate in counseling sessions, and willing to complete 15 total appointments (six during NRT treatment, eight retention contacts, and final exit interview survey) over the 26-week study period. Current smoking was defined as having smoked at least 100 cigarettes in their lifetime plus smoking at least 1 cigarette/day (CPD) in the prior 7 days. Exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) test was used to confirm smoking status due to concerns that some might overreport their baseline smoking status to gain incentives. Individuals with CO scores above 5 ppm were included in the study, a criteria based on prior studies (Middleton & Morice, 2000; Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 2002; Tonnesen, Norregaard, Mikkelsen, Jorgensen, & Nilsson, 1993). Participants were determined to be homeless based on the definition established by the Stewart B. McKinney Act, passed by the U.S. congress in 1987. Homelessness was defined as “any individual who lacks a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence” or “one whose primary nighttime residence is a supervised publicly or privately operated shelter designed to provide temporary living accommodations, transitional housing, or other supportive housing program or a public or private place not meant for human habitation (e.g., on the streets or in abandoned buildings, tents, or automobiles)” (Hwang, 2000; U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 1987; Wilder Foundation, 2009).

Figure 1.

Screening and enrollment of study participants.

Intervention Components

Intervention components of the study have been described in detail elsewhere (Goldade et al., 2011) but summarized briefly below.

Motivational Interviewing

MI is designed to enhance motivation for change (Miller & Rollnick, 2002). Participants in the intervention arm received six MI counseling sessions from trained Bachelors- and Masters-level counselors each lasting approximately 20 min. To ensure fidelity to MI treatment, all sessions were audio recorded and reviewed during weekly supervision with a licensed clinical psychologist trained in MI. During weekly supervision meetings, tapes were reviewed for treatment fidelity and direct instruction. In addition to ongoing supervision, at the initiation of the project, the MI counselors received two full days of training on the theory and method of conducting MI counseling sessions and approximately 40 hr of supervised training. MI counselors only provide counseling to participants in the MI arm.

Standard Care

Participants in the control comparison condition received “SC,” a 1-time session of health education and brief advice to quit smoking which lasted approximately 20 min, consistent with current smoking cessation clinical practice guidelines (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000). To ensure fidelity, all SC sessions were audio recorded and reviewed during weekly supervision with doctoral-level coinvestigators. During weekly supervision meetings, tapes were reviewed for treatment fidelity and direct instruction. The counselors received one full day of training on SC counseling sessions and approximately 40 hr of supervised training. SC counselors only provide counseling to participants in the SC arm.

Measures

Overall, measures were taken from previously validated surveys and instruments. Baseline assessment of demographic information included age, ethnicity, gender, income, education level, marital status, employment status, psychosocial variables such as social support, and the degree of homelessness experienced such as number and duration of homeless episodes (Everson et al., 1996; Everson, Kaplan, Goldberg, & Salonen, 2000). Metric measurements of height and weight were collected to calculate body mass index. CO and serum cotinine were assessed as biomarkers of baseline tobacco use. Smoking history assessment included the current number of cigarettes smoked per day, age of regular smoking, amount spent on cigarettes per week, daily or nondaily smoking, and type of cigarettes smoked (mentholated or nonmentholated). Quitting history was assessed by asking the number of quit attempts in the past year that lasted 24 hr or longer (Ahluwalia et al., 2006; Ahluwalia, Harris, Catley, Okuyemi, & Mayo, 2002; Ahluwalia, Richter, Mayo, & Resnicow, 1999). Motivation and confidence for quitting were assessed using a 10-point Likert scale with a higher score indicating greater motivation or confidence (Ahluwalia et al., 1999, 2002, 2006). Nicotine dependence was assessed using one item from the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scale that asked about time to first cigarette of the day (Heatherton, Kozlowski, Frecker, & Fagerström, 1991). Participants were also asked the number of their five best friends who smoked cigarettes. The Questionnaire of Smoking Urges (Cox, Tiffany, & Christen, 2001) was used to assess urge to smoke. Mental health measures included psychiatric comorbidities assessed with the Rost–Burnham screener for past year depression (Rost, Burnam, & Smith, 1993), the 9-item patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) for depression in past 2 weeks (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002), and the 4-item perceived stress scale for stress in past 30 days (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). Furthermore, study participants were asked questions on drug treatment history and drug and alcohol dependence with the Rost–Burnham screener for lifetime drug (marijuana, cocaine, and heroin) and lifetime alcohol dependence (Rost et al., 1993). Cognitive impairment was assessed with the Short Blessed Test (Katzman et al., 1983), a 6-item test for differentiating cognitive impaired patients from normal population.

Analysis

We calculated the descriptive statistics of the baseline sociodemographic and homelessness characteristics, smoking and other drug use characteristics, and general and mental health profile for the study sample. Categorical variables were summarized by frequencies and percentages, and continuous variables were summarized by means and SD.

Results

A total of 839 individuals who indicated interest in the study completed the eligibility survey. Of these, 568 (67.7%) were eligible. Among those eligible, 138 (24.3%) participants did not keep their randomization appointment. The remaining 430 (75.7%) were randomized into the two study conditions over a 15-month period. Figure 1 shows the flow of events from assessment of eligibility through randomization. Common reasons for ineligibility included CO less than 5 ppm (30.4%), use of other smoking cessation aids in prior 30 days (22.5%), not homeless (21.3%), short duration of stay in the Twin Cities area (17.4%), or cognitive impairment that limits their ability to complete the surveys (13.1%).

Table 1 shows the baseline sociodemographic characteristics of the 430 baseline participants who were predominantly Black (56.3%) or White (35.6%), male (74.7%), had mean age of 44.4 years (S D = 9.9; range 19–67), and completed at least high school education or equivalent (76.7%) and the majority were unemployed (90.5%). When asked where they usually slept in the prior 6 months, nearly two thirds reported sleeping in emergency shelters and 15% slept in transitional housing. Nearly half of the sample had been homeless for more than a year, and 15% had been homeless for more than 3 years. Forty-three percent of the sample was experiencing homelessness for the first time, but 31.8% had been homeless three or more times in the past 3 years.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Homelessness Characteristics of430 Homeless Adults in the Power To Quit Study

| Variable | N | % or M (SD) |

| Age | 430 | 44.4 (9.9) |

| Gender, male | 430 | 74.7 |

| Education, % ≥high school or equivalent | 330 | 76.7 |

| Unemployed | 430 | 90.5 |

| Monthly income, US$ | ||

| <$400 | 273 | 63.5 |

| $400–$799 | 87 | 20.2 |

| ≥$800 | 50 | 16.3 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| African American/Black | 242 | 56.3 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 10 | 2.3 |

| Native American | 10 | 2.3 |

| White | 153 | 35.6 |

| Other | 15 | 3.5 |

| Usual housing status in past 6 months | ||

| On street | 34 | 7.9 |

| Emergency shelter | 258 | 60.0 |

| Friend or relative's house | 40 | 9.3 |

| A house, apartment, mobile home, or condo | 23 | 5.3 |

| Transitional housing | 65 | 15.1 |

| Other | 10 | 2.3 |

| Duration of current homeless episode | ||

| <1 month | 9 | 2.1 |

| 1–3 months | 73 | 17.0 |

| 4–6 months | 61 | 14.2 |

| 7–11 months | 72 | 16.8 |

| 1–3 years | 151 | 35.2 |

| >3 years | 63 | 14.7 |

| Number of times homeless in past 3 years | ||

| Just once | 185 | 43.2 |

| Two times | 107 | 25.0 |

| Three times | 45 | 10.5 |

| Four or more times | 91 | 21.3 |

Smoking characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 2. Nearly all the participants were daily smokers (96.7%), and nearly two thirds (62.6%) smoked mentholated cigarettes. In addition, participants reported smoking an average of 19.3 CPD, have smoked regularly since 16 years of age, and spent on average US$27.5 per week on cigarettes. Nearly half (47.2%) of the study sample smoked their first cigarette within 5 min of awakening, and 87.0% smoked within 30 min of awakening. Overall, participants rated quitting smoking as very important to them (9.1 on a 10-point scale) and were modestly confident they could quit smoking (7.3 on 10-point scale). Participants reported having made on average 2.5 smoking quit attempts lasting 24 hr or longer in the past year.

Table 2.

Smoking Characteristics of 430 Homeless Adults in the Power to Quit Study

| Variable | N | % or M (SD) |

| Cigarettes/day | 427 | 19.3 (13.7) |

| Smoke every day | 430 | 96.7 |

| Age of onset of regular smoking | 430 | 16.2 (5.9) |

| Smoke mentholated cigarettes | 428 | 62.6 |

| Amount spent on cigarettes/week, US$ | 428 | 27.5 (16.6) |

| Time to first cigarette of the day after awakening | ||

| 0–5 min | 203 | 47.2 |

| 6–15 min | 104 | 24.2 |

| 16–30 min | 67 | 15.6 |

| >30 min | 56 | 13.0 |

| Number of five best friends who smoke cigarettes, M (SD) | 429 | 4.1 (1.4) |

| Number of quit attempts in past year | 424 | 2.5 (5.2) |

| Importance of quitting (scale 1–10) | 430 | 9.1 (1.6) |

| Confidence to quit (scale 1–10) | 430 | 7.3 (2.4) |

| Exhaled carbon monoxide, ppm | 409 | 15.6 (8.9) |

| Salivary cotinine, ng/ml | 409 | 213 (159) |

Table 3 presents self-reported general and mental health characteristics of study sample. The majority of participants reported they were in good or better state of general health. Nearly three fourths were either overweight or obese. Nearly 40% of participants had PHQ-9 depression screening scores in the moderate or worse range. More than 80% of the sample screened positive for lifetime history of drug abuse or dependence, while 55% screened positive for lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence.

Table 3.

General Health, Mental Health, Alcohol Use, and Other Drug Use of 430 Homeless Adults in the Power to Quit Study

| Variable | N | % or M (SD) |

| Self-rated general health | ||

| Excellent | 67 | 15.7 |

| Very good | 113 | 26.4 |

| Good | 144 | 33.6 |

| Fair | 84 | 19.6 |

| Poor | 20 | 4.7 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 426 | 30.1 (7.6) |

| Normal (≥18.5 <25) | 113 | 26.5 |

| Overweight (>25 <30) | 148 | 34.7 |

| Obese (≥30) | 165 | 38.7 |

| Perceived stress, M | 428 | 8.4 (2.3) |

| Patient health questionnaire-9 | 428 | 8.34 |

| None (0–4) | 146 | 34.1 |

| Mild (5–9) | 113 | 26.4 |

| Moderate (10–14) | 86 | 20.1 |

| Moderately severe (15–19) | 61 | 14.3 |

| Severe (20–27) | 22 | 5.1 |

| Consumed alcoholic drinks in past 30 days | 246 | 57.5 |

| Number of days drank alcohol in last 30 days | 246 | 8.6 (10.1) |

| Number of drinks per day in last 30 days | 245 | 4.5 (4.2) |

| Number of days of binge drinking in last 30 days | 231 | 7.4 (7.9) |

| Importance of quitting drinking (scale 1–10) | 424 | 7.6 (3.6) |

| Confidence for quitting drinking (scale 1–10) | 424 | 8.4 (2.6) |

| Drug abuse/dependence | ||

| Ever used any illicit drug more than five times in lifetime, % yes | 355 | (82.8) |

| Needed to use larger amounts of drugs to get effect, % yes | 170 | (39.6) |

| Had emotional/psychological problems from using drugs, % yes | 140 | (32.6) |

| Marijuana use | ||

| Ever used | 174 | 40.7 |

| Used in last 30 days | 142 | 33.1 |

| Days used in last 30 days | 142 | 9.3 (9.6) |

| Cocaine use | ||

| Ever | 253 | 59 |

| Used in last 30 days | 40 | 9.3 |

| Days used in last 30 days | 40 | 4.4 (5.7) |

| Consider self as alcoholic or chemically dependent | 429 | 42.7 |

| Received drug or alcohol treatment in last 2 years | 108 | 25.2 |

Discussion

The current paper describes the baseline characteristics of the first large smoking cessation randomized clinical trial designed for homeless smokers. Due to the challenges anticipated for recruiting study participants in this population, investigators had projected that recruitment would take 24 months or more. However, recruitment of the 430 participants needed for the study was completed within 15 months. Completing recruitment within this timeframe demonstrates the feasibility of identifying and enrolling smokers in homeless populations into a smoking cessation clinical trial, specifically, a study using nicotine patch and MI counseling.

The population enrolled in this current study is novel in several respects relevant to real-world use of evidence-based smoking cessation interventions. The demographic characteristics of smokers in this study are quite different from those of studies that established the efficacy of the nicotine patch (Foulds et al., 1993; Law & Tang, 1995; Fiore, Smith, Jorenby, & Baker, 1994; Tang, Law, & Wald, 1994). While the vast majority of participants in most smoking cessation studies were female and Whites, the current study successfully recruited a predominantly male and ethnically diverse sample. That the study sample was disproportionately Black, adult male, is comparable to those in two previous pilot clinical trials with homeless smokers (Okuyemi et al., 2006; Shelley, Cantrell, Wong, & Warn, 2010) conducted in different U.S. cities. Also, while the housing situation (i.e., homeless or not) and socioeconomic status of participants typically was not stated in the earlier NRT efficacy studies, the settings from which participants were recruited suggest a middle-class socioeconomic status background. In contrast, all participants in the current study were homeless, 25% had less than high school education, and 90% were unemployed. Diversity of the study sample is also reflected by the variation in the type of shelter (emergency shelter, transitional housing, and on the street) and by the duration of homelessness (short-term vs. chronically homeless). The uniqueness of this study sample creates an opportunity, at the end of the study, for investigators to be able to examine the relationship between smoking cessation outcomes and these demographic and homelessness characteristics.

These baseline results also showed the study sample to be highly nicotine dependent as indicated by participants smoking an average of 20 CPD, nearly all being daily smokers, and 87% smoked their first cigarette within 30 min of awakening. Also, despite their very low socioeconomic status, participants reported spending nearly $28 a week on cigarettes. Despite these indicators of high nicotine dependence, participants were highly motivated to quit and modestly confident they would succeed in doing so. The high motivation to quit of smokers in this study coupled with their high degree of nicotine dependence underscores the need for extending smoking cessation programs to homeless populations. Despite the participants’ high level of motivation to quit smoking, the high degree of nicotine dependence suggests that quitting will nevertheless be challenging. Studies have shown that nicotine dependence is negatively correlated with success for quitting smoking (Fagerström, Hughes, Rasmussen, & Callas, 2000; Fagerström & Sawe, 1996; Fiore et al., 2000). The cessation outcomes of the parent study will therefore fill an important gap in the literature about effects of evidence-based cessation interventions in a population of homeless smokers with high nicotine dependence.

This study also showed that in this sample of smokers, there were high rates of comorbidities with depression, alcohol, and other substance abuse with nearly 40% having PHQ-9 scores in the moderate or worse depression range and nearly half considering themselves as being alcoholic or chemical dependent. Studies (Humfleet, Munoz, Sees, Reus, & Hall, 1999; Sullivan & Covey, 2002; Torchalla et al., 2011) in other populations have shown that these comorbidities make quitting smoking more challenging. However, there are currently no data about the effects of these comorbidities on smoking cessation in homeless populations. Unlike the typical protocol of smoking cessation studies in the general population that excludes smokers with these comorbid conditions, smokers with these conditions were allowed to enroll in this study, provided they were medically stable as determined by a psychiatrist. This protocol decision was made to ensure that the study sample would be similar to homeless smokers in general, which would enhance the study’s external validity. Findings from the final outcomes of this trial will provide guidance regarding addressing these comorbidities in the context of smoking cessation interventions.

This study has some limitations. First, the study was conducted at a single metropolitan area in the upper Midwest of the United States, and there may be differences between cities, states, or regions within a country and between countries that could affect sociodemographic characteristics of homeless persons enrolled in a smoking cessation study. However, several demographic and substance use characteristics of study participants are comparable with those of homeless populations in other areas (Wilder Foundation, 2009). Second, because this study was a treatment study, the sample was self-selected and motivated to quit smoking and thus may not be representative of homeless smokers generally. The high motivation of participants may also make MI less effective since MI is best suited for less motivated people. However, the study was designed with minimal exclusion criteria so that the external validity of findings would be enhanced. Given the high motivation for smoking cessation among homeless smokers, future studies should consider either enrolling only less motivated smokers for whom MI would be better suited or utilized a different counseling technique such as cognitive behavioral therapy. However, the decision to enroll a more “selective” population should be weighed with the potential ethical implications of excluding motivated smokers in a population already disenfranchised from clinical research.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the feasibility of identifying and enrolling a diverse sample of homeless smokers into a smoking cessation clinical trial with 6 months follow-up. Completing enrollment on schedule provides additional evidence that homeless smokers are interested in engaging in a clinical study to help them quit. Outcome results at 6 months will provide relevant information regarding adherence to study protocol, retention rates over 6 months, verified quit rates, as well as moderating effects of substance abuse and psychiatric comorbidities on cessation outcomes. Given the high prevalence of smoking and high interest in quitting despite unique socioeconomic challenges within homeless populations, the public health community ought to redouble its efforts to extend evidence-based smoking cessation interventions to homeless populations. Such efforts are critical for reducing tobacco-related health disparities within vulnerable groups.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL081522).

Declaration of Interests

Authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jennifer Warren, Ph.D., and project staff Sharae Walker, Bonnie Houg, R’Gina Sellers, Casey Tuck, Abimbola Olayinka, Carolyn Borja, Carolyn Bramante, Julia Davis, Pravesh Napaul, and Brandi White for their assistance with implementation of the project. The authors further acknowledge the directors and staff of participating shelters, Dorothy Day Center, Our Savior’s Shelter, Listening House, Union Gospel Mission, Naomi Family Center, and People Serving People. Finally, we express gratitude to the members of the Community Advisory Board and the study participants.

References

- Ahluwalia JS, Harris KJ, Catley D, Okuyemi KS, Mayo MS. Sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation in African Americans: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:468–474. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.4.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia JS, Okuyemi K, Nollen N, Choi WS, Kaur H, Pulvers K, et al. The effects of nicotine gum and counseling among African American light smokers: A 2 × 2 factorial design. Addiction. 2006;101:883–891. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahluwalia JS, Richter KP, Mayo MS, Resnicow K. Quit for life: A randomized trial of culturally sensitive materials for smoking cessation in African Americans. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 1999;14(Suppl. 2):6. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor SE, Cook RL, Herbert MI, Neal SM, Williams JT. Smoking cessation in a homeless population: There is a will, but is there a way? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2002;17:369–372. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10630.x. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10630.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox LS, Tiffany ST, Christen AG. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2001;3:7–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200020032051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- el-Guebaly N, Cathcart J, Currie S, Brown D, Gloster S. Smoking cessation approaches for persons with mental illness or addictive disorders. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:1166–1170. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.9.1166. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.53.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson SA, Goldberg DE, Kaplan GA, Cohen RD, Pukkala E, Tuomilehto J, et al. Hopelessness and risk of mortality and incidence of myocardial infarction and cancer. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1996;58:113–121. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson SA, Kaplan GA, Goldberg DE, Salonen JT. Hypertension incidence is predicted by high levels of hopelessness in Finnish men. Hypertension. 2000;35:561–567. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.2.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström KO, Hughes JR, Rasmussen T, Callas PW. Randomised trial investigating effect of a novel nicotine delivery device (eclipse) and a nicotine oral inhaler on smoking behaviour nicotine and carbon monoxide exposure and motivation to quit. Tobacco Control. 2000;9:327–333. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagerström KO, Sawe U. The pathophysiology of nicotine dependence: Treatment options and the cardiovascular safety of nicotine. Cardiovascular Risk Factors. 1996;6:135–143. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M, Bailet WC, Cohen SJ, et al., editors. Treating tobacco use and dependence. Washington, DC: United. States Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Fiore MC, Smith SS, Jorenby DE, Baker TB. The effectiveness of the nicotine patch for smoking cessation. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1994;271:1940–1947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foulds J, Stapleton J, Hayward M, Russell MAH, Feyerabend C, Fleming T, et al. Transdermal nicotine patches with low-intensity support to aid smoking cessation in outpatients in a general hospital—a placebo-controlled trial. Archives of Family Medicine. 1993;2:417–423. doi: 10.1001/archfami.2.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldade K, Whembolua G, Thomas J, Eischen S, Guo H, Connett J, et al. Designing a smoking cessation intervention for the unique needs of homeless persons: A community-based randomized clinical trial. Clinical Trials. 2011;8:744–754. doi: 10.1177/1740774511423947. doi: 8/6/744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humfleet G, Munoz R, Sees K, Reus V, Hall S. History of alcohol or drug problems, current use of alcohol or marijuana, and success in quitting smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 1999;24:149–154. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00057-4. doi:S0306-4603(98)00057-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SW. Mortality among men using homeless shelters in Toronto, Ontario. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:2152–2157. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.16.2152. doi:10.1001/jama.283.16.2152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SW, Orav EJ, O’Connell JJ, Lebow JM, Brennan TA. Causes of death in homeless adults in Boston. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1997;126:625–628. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-8-199704150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, Schimmel H. Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1983;140:734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32:509–515. [Google Scholar]

- Lam TH, Abdullah AS, Chan SS, Hedley AJ. Adherence to nicotine replacement therapy versus quitting smoking among Chinese smokers: A preliminary investigation. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;177:400–408. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-1971-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M, Tang JL. An analysis of the effectiveness of interventions intended to help people stop smoking. Archives of Internal Medicine. 1995;155:1933–1941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton ET, Morice AH. Breath carbon monoxide as an indication of smoking habit. Chest. 2000;117:758–763. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.3.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Okuyemi K, Thomas J, Hall S, Nollen N, Richter K, Jeffries S, et al. Smoking cessation in homeless populations: A pilot clinical trial. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8:689–699. doi: 10.1080/14622200600789841. doi:10.1080/14622200600789841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost K, Burnam MA, Smith GR. Development of screeners for depressive disorders and substance disorder history. Medical Care. 1993;31:189–200. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelley D, Cantrell J, Wong S, Warn D. Smoking cessation among sheltered homeless: A pilot. American Journal of Health Behaviors. 2010;34:544–552. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.34.5.4. doi:10.5555/ajhb.2010.34.5.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Rolf CN, Hellebusch SJ, Gorsline J, Gorodetzky CW, Chiang YK, et al. Real-world efficacy of prescription and over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy. Addiction. 2002;97:505–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2002;4:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MA, Covey LS. Current perspectives on smoking cessation among substance abusers. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2002;4:388–396. doi: 10.1007/s11920-002-0087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JL, Law M, Wald N. How effective is nicotine replacement therapy in helping people to stop smoking? British Medical Journal. 1994;308:21–26. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6920.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teeter T. Adherence: Working with homeless populations. Focus. 1999;14:5–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonnesen P, Norregaard J, Mikkelsen K, Jorgensen S, Nilsson F. A double-blind trial of a nicotine inhaler for smoking cessation. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1993;269:1268–1271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torchalla I, Strehlau V, Okoli CT, Li K, Schuetz C, Krausz M. Smoking and predictors of nicotine dependence in a homeless population. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2011;13:934–942. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr101. doi:10.1093/ntr/ntr101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States. (2004). U.S. Code, Title 42, Chapter 119, Subchapter I, Section 11302. Retrieved from http:/www4.law.cornell.edu/usdoce/42/11302.html.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The tobacco use and dependence clinical practice guideline panel staff and consortium representatives. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2000;283:3244–3254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. General definition of homeless individual. US Code Collection, Sec. 11302. 1987. Retrieved from http://www4.law.cornell.edu/uscode/42/11302.html.

- Wilder Foundation. Homeless adults and children in Minnesota statewide survey. 2004. Retrieved from http://www.wilder.org/fileadmin/user_upload/research/Homeless2003/adult/StatewideAdultsByMetroGreaterMN_Tables_192–199.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wilder Foundation. Homelessness in Minnesota: Key findings from the 2009 statewide survey. 2009. Retrieved from http://www.wilder.org/reportsummary.0.html?tx_ttnews[tt_news]=2300. [Google Scholar]