Abstract

To examine the relationship between smoking and AD after controlling for study design, quality, secular trend, and tobacco industry affiliation of the authors, electronic databases were searched, 43 individual studies met the inclusion criteria. For evidence of tobacco industry affiliation http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu was searched. One fourth (11/43) of individual studies had tobacco affiliated authors. Using random effects meta-analysis, 18 case control studies without tobacco industry affiliation yielded a non-significant pooled odds ratio of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.75–1.10), while 8 case control studies with tobacco industry affiliation yielded a significant pooled odds ratio of 0.86 (95% CI, 0.75–0.98) suggesting that smoking protects against AD. In contrast, 14 cohort studies without tobacco industry affiliation yielded a significantly increased relative risk of AD of 1.45 (95%CI, 1.16–1.80) associated with smoking and the three cohort studies with tobacco industry affiliation yielded a non-significant pooled relative risk of 0.60 (95% CI 0.27–1.32). A multiple regression analysis showed that case-control studies tended to yield lower average risk estimates than cohort studies (by −0.27±0.15, P=.075), lower risk estimates for studies done by authors affiliated with the tobacco industry (by −0.37±0.13, P=.008), no effect of the quality of the journal in which the study was published (measured by impact factor, P=0.828), and increasing secular trend in risk estimates (0.031/year ±.013, P=.02). The average risk of AD for cohort studies without tobacco industry affiliation of average quality published in 2007 was estimated to be 1.72±0.19 (P<.0005). The available data indicate that smoking is a significant risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.

Keywords: smoking, Alzheimer disease, cigarette and cognition, tobacco and cognitive impairment

INTRODUCTION

In 2006, there were 26.6 million people with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). AD prevalence will quadruple by 2050, increasing the burden of care and the associated health costs.[1] Cardiovascular disease is a major risk factor for AD[2] and smoking cigarettes causes cardiovascular disease.[3, 4] Despite a growing body of evidence linking smoking with AD,[5–8] beliefs prevail that smoking protects against AD in both scholarly journals and lay publications.[9–13] For example, a 2008 study of nicotine dependence in Human Genetics begins with the statement, “epidemiological studies reveal that cigarette smoking is inversely associated with AD”[14] the “Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures,”[15] published by the Alzheimer’s Association, does not mention smoking and the May 8, 2008 Oprah Magazine, a trusted source of health information for millions of women, reported that nicotine might protect people from AD.[16] As of October 2008, over 100 web sites stated that smoking was protective for AD. Confusion regarding the role of smoking in AD may discourage cessation attempts among older smokers and contribute to the reluctance of health care providers to treat tobacco dependence in older smokers.[17] A delay in AD onset or progression by just one year would result in nearly 9.2 million fewer cases in 2050.[1] There is a pressing need to understand the risk factors for AD, particularly clarification of smoking’s effect.

Previous reviews[5–13, 18] of the association between smoking and AD have not controlled for both study design and author affiliation with the tobacco industry. In 2002, Almeida et al.[5] identified study design (cohort or case-control) as an important methodological issue because of survival and recall bias that may be responsible for the unclear direction of the association between smoking and AD. But, at the time, only four cohort studies were available, and the direction of the association remained unclear.[5] In 2007, Anstey et al.[6] published a meta-analysis of 19 cohort studies and found that, compared with people who had never smoked, current smokers had an increased risk of AD. Hernan et al.[7] identified 12 prospective studies and found a wide range of risks for AD associated with smoking, which they attributed to bias due to censoring by death. Purnell’s[8] 2008 systematic review of cardiovascular risk factors and incident AD reported on only four cohort studies that used incident cases of AD, three of which reported that current smoking increased the risk of AD and one found no significant relationship.

As early as 1976, the tobacco industry began to invest in AD research,[19, 20] with the goal of developing nicotine-related diagnostics and therapeutics.[21] These research efforts were conducted through the industry’s Council for Tobacco Research (CTR) and the individual tobacco companies (RJ Reynolds [RJR] Biomedical Research Program[19, 20] and Philip Morris Research[22]). CTR’s interest in AD started in 1981 following published anecdotal observations of low rates of tobacco use among patients with AD.[23, 24] In 1987, RJR’s “Smoking and Health's contract program” identified several key research areas, including the “possible relationships between smoking and Alzheimer's Disease.”[25] In 1993, Philip Morris’ interests in AD research were to “not only understand the role of smoking in this disorder but also provide early diagnostics … as well as potential therapeutics (e.g., nicotine analogs).”[21]

Past research has shown that the tobacco industry funding of research on the health risks of smoking is associated with findings that support their position. For example, research showing that factors like genetics, personality type or aging were responsible for diseases such as lung cancer and cardiovascular disease.[26–28] Industry sponsored research is more likely to reach conclusions that are favorable to the sponsor and experience publication bias, publication delays and data withholding.[29] This has been true for sponsorship not only from the tobacco industry[30, 31] but also from the pharmaceutical[32, 33] and chemical industries.[34] The present systematic review estimates the association between cigarette smoking and AD after controlling for study design, quality, secular trend and tobacco industry affiliation of the authors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of Relevant Research Publications

We searched PubMed, PsycINFO, Google Scholar, and Cochrane CENTRAL for reviews and individual studies published as full articles or brief reports using combinations of keywords for smoking (smoking, tobacco, cigarettes and nicotine) and AD (Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, cognition, cognitive impairment, vascular dementia). We also examined reference lists of prior reviews and individual studies and contacted experts in the field. For inclusion, studies needed to be published, use AD as the outcome (not dementia or cognitive decline), human subjects (brain tissue excluded), a measurement of smoking (i.e., ever smoker, current smoker, never smoker), and have a clearly stated study design (case-control or cohort). One prevalence study[35] was included and coded as a case-control study. If both raw and adjusted risk ratios were available, ratios adjusted for the most covariates were used.

The initial search returned 336 articles; 47 met the requirement for detailed review, of which 43 original research studies met our inclusion criteria (Table 1 and Table 2 and Figure 1). One publication was excluded because it was a letter to the editor and the criteria used for diagnosis of AD were unclear.[36] One other publication was excluded[37] because results from the same study were published in two papers, and we included the more completely reported results.[38] For multiple publications from the same sample with the same smoking measures, we used the publication with the longest follow-up; in particular, for the Rotterdam Study, the latest 2007 report[39] was chosen over the 1998 report[40] and for the Canadian Study of Health and Aging the 2002 report[41] was chosen over the three previous reports.[42–44] When the studies were stratified by race,[45, 46] results for the separate populations were included as separate studies. A paper by Wang (1999) provided both case-control and cohort results, which also were treated as separate studies.[47]

Table 1.

Case-control studies investigating the association between smoking and Alzmeimer’s disease

| No tobacco industry affiliation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, year | # of cases /#who smoked |

# of controls/ #who smoked |

OR | 95%CI | Estimates Adjusted for |

Source of Cases |

Source of Controls |

Smoking Exposure Measure |

Outcome Measure/ Diagnosis of AD |

Tobacco Industry Affiliation |

Industry Affiliation Disclosed in Published Article*** |

| Amaducci et al., 1986[65] | 51/116 | 52/97 | 1.83 | 0.62–6.04 | Age, sex, region of residence | Dept of Neurology | Hospital or community acquaintance | Ever smoked ≥ 10 cig/day Never | Clinical assessment and Blessed Dementia Scale | None | |

| Brenner et al., 1993[66] | 152/? | 180/? | 0.61 | 0.37–0.99 | Age, gender, education, race, hypertension | AD registry | Same population as cases | Ever/Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Broe et al., 1990[67] | 170/80 | 170/88 | 0.76 | 0.44–1.31 | Age, gender, general practice of origin | Dementia clinics | Same referring practice | Ever ≥ 1 pk cigs/day Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Chandra et al., 1987[68] | 62/16 | 62/22 | 0.57 | 0.21–1.46 | Age, race, gender, agents, education, occupation | Seniors out patient clinic | Non-demented same clinic | Unclear | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Debanne et al., 2000[69]** | 86/49 | 152/78 | 1.26 | 0.66–2.42 | Research Registry at AD Center | siblings | Ever/Never | Blessed Dementia Scale | Not for this work** | ||

| Ferini-Strambi et al., 1990[70] | 63/16 | 126/53 | 0.47 | 0.24–0.91 | Age, gender, residential area, education, social status, age of onset | Department Neurology | Case neighbors | Ever ≥ 10cig/day after the age of 30 Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Forster et al., 1995[71] | 109/66 | 109/77 | 0.65 | 0.35–1.17 | Age, gender, atherosclerotic disease | Referrals to specialist hospital services | Random from same population | Ever/Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| French et al., 1985[72] | 78/54 | 48/37 | 0.50 | 0.15–1.66 | Age, race, gender | VA hospital | Hospital and neighborhood | Unclear | Insidious onset, gradual progression of dementia intact LOC | None | |

| Harwood et al., 1998[46]white non-Hispanic | 392/58 | 202/59 | 1.10 | 0.70–1.60 | Age, gender, education, ethnicity | AD center | Non-demented from same center | Ever/Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Harwood et al., 1998[46]white Hispanic | 188/30 | 84/36 | 1.00 | 0.50–1.90 | Age, gender, education, ethnicity | AD center | Non-demented from same center | Ever/Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Heyman et al., 1984[73] | 12/40 | 25/80 | 0.94 | 0.40–2.13 | Age, gender, race | Epidemiology study database | Telephone sample | Ever ≥ 1pk/day after 40 yo Never | unclear | None | |

| Maia et al., 2002[74] | 54/? | 54/? | 1.41 | 0.59–3.33 | Age. Gender, monozygotic/dizygotic | Dementia Outpatient Clinic | Accompanied patient | Never, Past, Current | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Prince et al., 1994[75] | 19/4 | 118/13 | 2.15 | 0.66–7.17 | Age, gender, hypertension | Study of hypertension | Same population | Current smoking Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Salib et al., 1997[38] | 198/72 | 176/72 | 0.83 | 0.54–1.25 | Age, gender, age of onset, duration of condition, history of head injury, and family history of dementia | Geriatric practice | Non-demented referrals | Ever/Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Shaji et al., 1996[76] | 27/3 | 34/4 | 0.94 | 0.21–4.16 | Age, gender, education | Community survey in India | Same population | Unclear | ICD-10 | None | |

| Shalat et al., 1987[77] | 98 | 162 | 1.53 | 0.74–3.17 | Gender, year of birth, town of residence, severe head trauma, alcohol consumption, education | Research Center | Neighbors | Ever/Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| van Duijn et al., 1991[78] | 193/89 | 195/102 | 0.70 | 0.43–1.15 | Age, gender, abnormalities on computed tomography, focal dysfunction on electroencephalography | Community | Community | Ever/Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Wang et al., 1997[79] | 98/45 | 97/26 | 1.73 | 0.8–2.66 | Age, gender, computerized tomography for vascular or other structural lesions. | Clinic | Spouses | Daily current or past/ Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Pooled **** | 0.91 | 0.75–1.10 | |||||||||

| Tobacco Industry Affiliation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bachman et al., 2003[45]African American | 285/97 | 158/54 | 1.00 | 0.69–1.50 | Age, race, education, alcohol exposure, head trauma, APOE-4 | African Americans in the MIRAGE study | Siblings | Ever /Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | Friedland team “participated with" [80] MIRAGE study group, shared data and co-authored on acknowledged tobacco funding publications [81, 82] | No |

| Bachman et al., 2003[45]White | 1,650/834 | 686/374 | 0.88 | 0.73–1.10 | Age, race, education, alcohol exposure, head trauma, APOE-4 | Whites in the MIRAGE study | Siblings | Ever/Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | Friedland team “participated with" [80] MIRAGE study group, shared data and co-authored on acknowledged tobacco funding publications [81, 82] | No |

| Barclay et al., 1989[83] | 14/39 | 12/39 | 1.26 | 0.50–3.20 | Age, gender, alcohol habits | Hospital notes | Spouses | Ever/Never | NIH criteria and Absence of symptoms compatible with vascular dementia | Funded by CTR 1985–1987[23, 83–85] | Yes |

| Bowirrat et al., 2001[35] | 168/30 | na* | 0.70 | 0.40–1.30 | Age, gender, education | Survey of Israeli community | Same population as cases | Yes is current or stopped ≥ 1 year ago or No | DSM-IV | Co-PI with Friedland at Tel Aviv University site, funded by PM[86] [87] | No |

| Graves et al., 1990[88] | 130/67 | 130/76 | 0.88 | 0.67–1.15 | Age | 2 clinics | Friend or surrogate | Ever (1 year prior to illness) | NINCDS-ADRDA | Co-PI with Friedland, funded by PM[89, 90] | No |

| Lerner et al., 1997[91] | 88/? | 176/? | 0.89 | 0.42–1.36 | Age, gender, estrogen replacement | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | NINCDS-ADRDA | Co-PI with Friedland, funded by PM [89, 90, 92, 93] | Yes |

| Plassman et al., 1995[94] | 65/? | 65/? | 0.66 | 0.33–1.35 | Twins | Twin discordant for AD | Ever (20 pack yr life time history) | NINCDS-ADRDA | Levin, Breitner, Welsh team funded by RJR [95–98] | Yes | |

| Wang et al, 1999[47] | 106/24 | 438/138 | 0.60 | 0.40–1.10 | Age, sex, education | Community | Community | Ever | DSM – III-R | Senior author Winblad, history of funding by Swedish Tobacco Co [99] | No |

| Pooled***** | 0.86 | 0.75–0.98 | |||||||||

unknown number of smokers

Prevalence study

Debanne is considered not tobacco industry affiliated for this study because the this work was done without Tobacco Industry affiliation. PM initially funded Debanne as Co-PI with Friedland, for a pilot study, but PM refused to continue to fund “siblingstudy” reported here.

Entries only for authors with industry affiliations

Q test for heterogeneity = 23.66, DF = 17, P = .129.

Q test for heterogeneity = 4.28, DF = 7, P = .748.

Table 2.

Cohort Studies Investigating The Association Between Smoking And Alzheimer’s Disease

| No Tobacco Industry Affiliation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Cohort, n |

Incident cases of AD with info about smoking |

RR | 95%CI | Estimates adjusted for |

Source of Cohort |

Duration of Follow- up |

Smoking Exposure Measure |

Outcome Measure/ Diagnosis of AD |

Tobacco industry affiliation |

Industry Affiliation Disclosed in Published Article* |

| Aggarwal et al., 2006[100] | 1,064 | 170 | 3.40 | 1.40–8.00 | Age, gender, race, APOE-4 | Chicago IL Community | 4.1 years | Current | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Broe, et al., 1998[101] | 327 | 31 | 1.03 | 0.45–2.37 | Age (at follow-up) gender, education | Community department of VA | 3 years | Current, Former, Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Doll et al., 2000[102] | 24,133 | 370 | 0.99 | 0.78–1.25 | Age, gender | Male British Doctors | 1950-death | Never, Ever, Continuing | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Hirayama et al., 1992[51] | 265,118 | 120 | 1.61 | 1.10–2.38 | Age, gender | Japanese Community | Up to 27 years (until death) | Daily, Occasionally, Former, Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Juan et al., 2004[103] | 2,820 | 84 | 2.72 | 1.63–5.42 | Age, sex, education, BP, and alcohol intake | Chinese Community | 2 years | Never and Current | MMSE and DSM-III-R | None | |

| Launer et al., 1999[104] | 10,889 | 145 | 1.74 | 1.00–2.40 | Age, age squared, study, sex, and education | EURODERM Eastern Europe community | 5-year bands | Ever | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Laurin et al., 2004[105] | 2,341 | 134 | 1.55 | 1.00– 2.40 | Age, education, alcohol intake, body mass index, physical activity, blood pressure, year of birth total energy intake, cholesterol concentration, history of CVD, supplemental vitamin intake, APOE-4, and Vitamin E | Hawaiian community, Japanese American Men | Varied, up to 2 times over 8 years | Never, Past, and Current | DSM-III; NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Lindsay et al., 2002[41] | 3,973 | 182 | 0.82 | 0.57–1.17 | Age, sex, education | Canadian Study of Health and Aging | 5 years | Ever | NINCDS-ARDA | None | |

| Luchsinger et al., 2005[106] | 1,012 | 61 | 2.0 | 1.3–3.2 | Age, sex, education, APOE-4, diabetes, hypertension, and heart disease | North Manhattan community | 1.5 years | Current, Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Merchant et al., 1999[107] | 1,204 | 142 | 1.90 | 1.20–3.0 | Education, ethnicity | Medicare recipients in 3 contiguous zip codes | Varied mean 1.7 years | Current, Former, Never | DSM-IVNINDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Moffat et al., 2004[108] | 572 | 54 | 1.86 | 1.39–2.49 | Age, education, BMI, diabetes, cancer, hormone supplementation, and free testosterone index | Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging | Varied 4-37 years; mean 19.1 years | Ever | DSM-III-RNINDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Piguet, et al., 2003[109] | 377 | 21 | 0.51 | 0.21–1.21 | Age at entry | Sydney Australia | 6 years | Smoking Nonsmoking | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Reitz, et al., 2007 [39] | 6,868 | 555 | 1.51 | 1.0–2.08 | Age, gender, APOE-4, education, alcohol intake | The Rotterdam Study | 7.1 years | Never, Past, Current | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Yoshitake et al., 1995[110] | 828 | 42 | 0.73 | 0.5–2.4 | Age, gender | Hisayama, Japan | 7 years | Ever, Never | NINCDS-ADRDA | None | |

| Pooled** | 1.45 | 1.16–1.80 | |||||||||

| Tobacco Industry Affiliation | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hebert et al., 1992[111] | 513 | 76 | 0.70 | 0.30–1.40 | Age, gender, education | Boston MA Community | 4.7 years | Ever | NINCDS-ADRDA | Worked with PN Lee and Paid consultant for PM[52, 54] | No |

| Katzman et al., 1989[112] | 434 | 32 | 0.27 | 0.11–0.61 | Age, gender | Bronx NY Volunteers | unclear | Current or Past | NINCDS-ADRDA | Paid consultant for CTR[113–115] | No |

| Wang et al., 1999[47] | 343 | 34 | 1.1 | 0.5–2.4 | Age, sex, education | Stockholm, Sweden | 3 years | Ever, Never | DSM-III-R | Senior author Winblad, history of funding by Swedish Tobacco Co [99] | No |

| Pooled*** | 0.60 | 0.27–1.32 | |||||||||

Entries only for authors with industry affiliations

Q test for heterogeneity = 43.34, DF = 13, P < .0005.

Q test for heterogeneity = 5.77, DF = 2, P = .056.

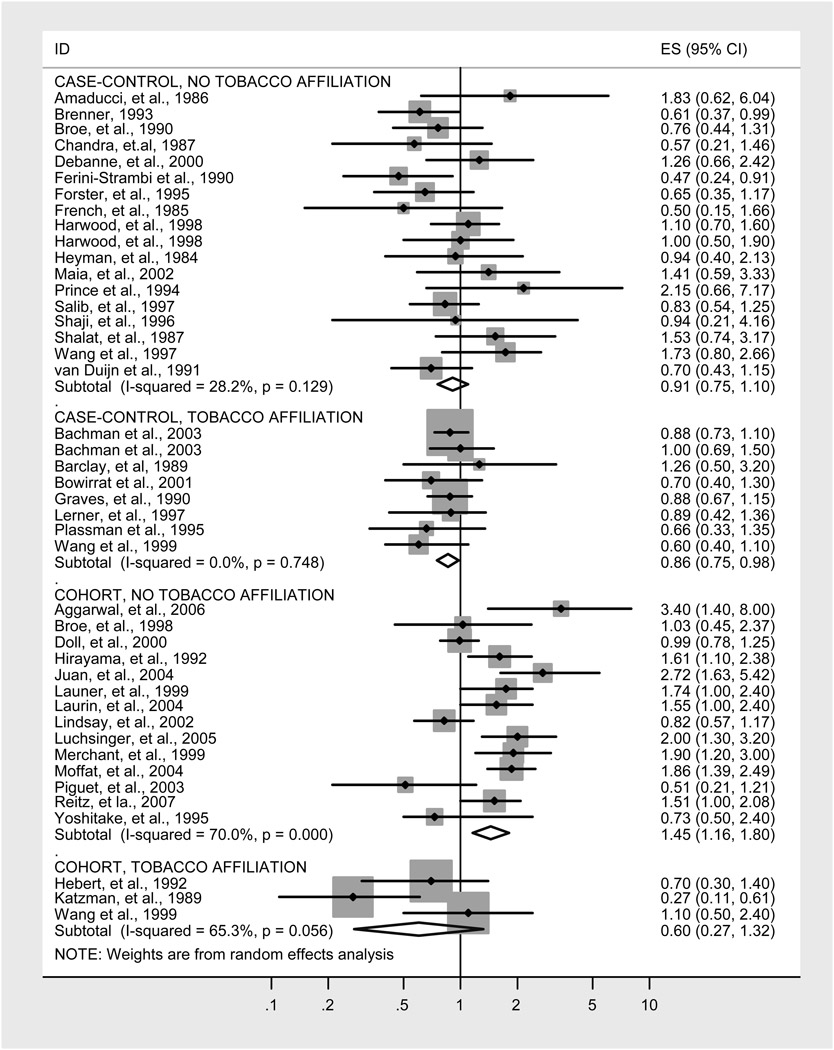

Figure 1.

Random effects meta-analysis of studies of AD.

For each study, we recorded the smoking exposure measure, method of diagnosing AD and covariates. For each case-control study, we recorded the number of cases and controls, the number of cases and controls who smoked, the source of cases and controls, and multivariate odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval and P value (Table 1). For each cohort study, we recorded the size and source of the cohort, years of follow-up, covariates, multivariate relative risk (RR), and confidence interval (Table 2).

Ten of the 43 studies were reviewed by two individuals, one reviewer blinded to author, journal, and publication date; there was 100% agreement.

We also identified 10 systematic reviews (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate determinants of AD risk

| Factor | Coefficient | SE | t | P | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case-control study design | −.27 | .15 | −1.83 | .075 | 1.39 |

| Journal Impact Factor* | −.002 | .009 | −0.22 | .828 | 1.16 |

| Year (2007 = 0) | .031 | .013 | 2.43 | .020 | 1.30 |

| Tobacco Affiliation | −.37 | .13 | −2.80 | .008 | 1.24 |

| Constant** | 1.72 | .19 | 8.84 | <.0005 |

N=43; R2 = 0.334; P=.006 for overall regression. Weights are sampling weights from random effects meta-analysis (Stata pweights).

Centered on mean value of 6.343

The constant is an estimate of the risk estimate based on a cohort study published in a journal with the average impact factor in 2007 by authors not affiliated with the tobacco industry.

Tobacco Documents Research

We searched the Legacy Tobacco Documents Library for evidence of tobacco industry affiliation of the studies’ authors (http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu), a collection of over 51 million pages of previously secret internal documents from the major tobacco companies and organizations that were made available as a result of litigation against the tobacco industry.[48, 49] Tobacco industry affiliation was defined as current or past funding, employment, paid consultation, collaboration, or co-authorship on the included study with someone with then-current or previous tobacco industry funding (within ten years of publication).

The search for possible tobacco industry affiliations was conducted from July 2006 to July 2008 using keywords “Alzheimer’s disease,” “dementia,” “cognition,” and the names of authors and university affiliations of the AD studies in this meta-analysis. Expanded searches were conducted using information in initially identified documents, including named individuals, specific programs, and dates and reference (Bates) numbers. Initial searches produced 10,798 documents. After screening documents based on index entries, we identified 3,324 documents to review. After eliminating duplicates and irrelevant documents, we analyzed 877 documents.

Statistical Analyses

In our meta-analysis we analyzed cohort studies (which yield direct estimates of relative risk) and case control studies (which yield odds ratios) separately. We tested for heterogeneity with the Q test statistic. Random effects meta-analysis was used to estimate pooled risk ratios and 95% confidence limits using the DerSimonian and Laird method because of observed heterogeneity among results among the cohort studies[50] (Stata 10.1 metan). We used Begg’s funnel plot to test for publication bias (Stata metabias).

We tested for the effect of study design, quality, secular trend and tobacco industry affiliation in a weighted (using weights from the meta-analysis using Stata regress option pweight) multiple regression analysis in which the dependent variable was the point estimate of the risk of AD and the independent variables were study design (0=case control, 1=cohort), study quality indexed as the impact factor of the journal (in 2009), where the study was published, secular trend (measured as year of publication, setting 2007 as 0) and tobacco industry affiliation (0=no, 1=yes). We selected 2007 as the base year because that was the year of the most recent individual study. Doing so gives the constant in the regression equation the following interpretation: The average risk estimate one would predict for a cohort study published in 2007 in an average quality journal by a group without tobacco industry affiliation. The choice of base year has no effect on the values, standard errors, or statistical significance of the predictor variables in the model.

Because the type of study design and likelihood of tobacco industry affiliation may have changed systematically over time, we computed variance inflation factors to test for collinearly in the independent variables in the regression analysis. We tested whether the model assumptions were met (linearity of the dependent variable and normality of error terms) by examining a normal probability plot of the residuals.

For review papers, we tested for a significant association between author affiliation with the tobacco industry and the conclusion of their review using a two tailed Fisher Exact Test, with reviews dichotomized into “protective” or “not protective or ambigous.”

RESULTS

Individual Studies and Meta-Analysis

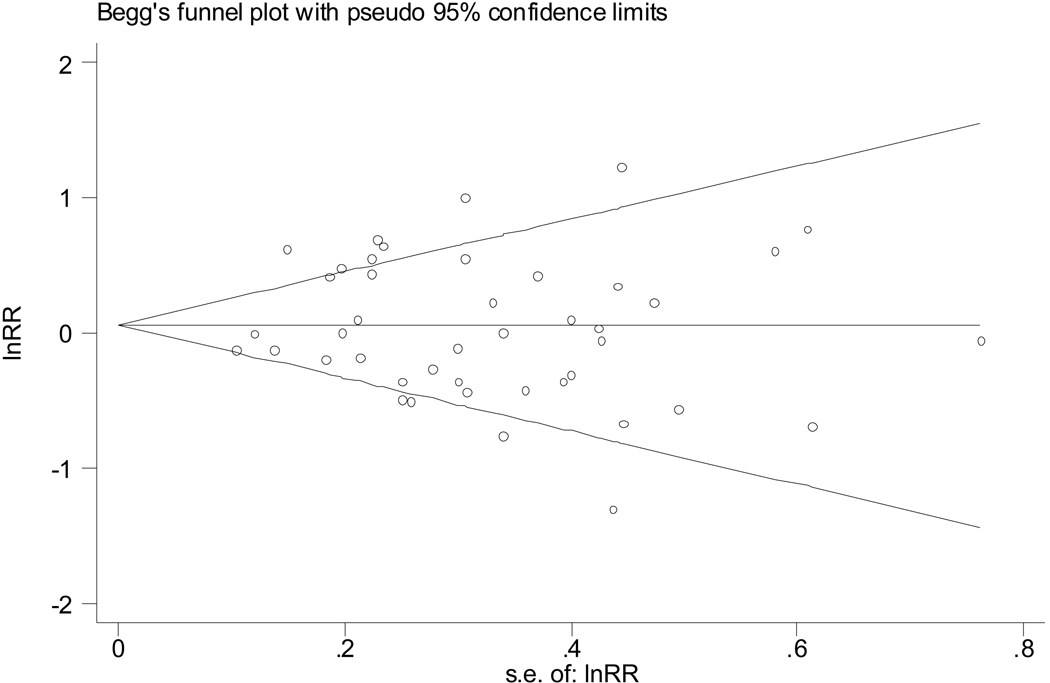

There was no evidence of publication bias (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A funnel plot shows no evidence of publication bias among all the studies (Begg’s Test P=.97). We also did a similar analysis for the four different subsets of studies (case-control, no tobacco affiliation, P = .544 by Begg’s test; case-control, tobacco affiliated, P=.476; cohort, no tobacco affiliation, P=.536; cohort, tobacco affiliation, P=.999), which also failed to find evidence of publication bias.

Of the 43 individual studies of smoking and AD (Figure 1), 26 were case-control studies (Table 1) and 17 were cohort studies (Table 2). Eleven of the 43 studies (26%) were conducted by tobacco industry affiliated investigators. Out of 11 tobacco affiliated studies only 3 disclosed an affiliation (27%). Of the 8 case control studies with tobacco affiliation, just 3 disclosed the affiliation (37%); of the 3 cohort studies with tobacco affiliation, none disclosed the affiliation.

The 18 case-control studies without tobacco industry affiliation yielded a nonsignificant pooled odds ratio of 0.91 (95% CI 0.75–1.10; Table 1 and Figure 1). In contrast, the 8 case-control studies with tobacco industry affiliation yielded a significant pooled odds ratio of 0.86 (95% CI 0.75–0.98; Table 1 and Figure 1), suggesting that smoking protects against AD. The 14 cohort studies without tobacco industry affiliation indicated a significantly increased relative risk of AD of 1.45 (95% CI 1.16–1.80; Table 2 and Figure 1) associated with smoking. In contrast, the three cohort studies with tobacco industry affiliation yielded a non-significant pooled relative risk of 0.60 (95% CI 0.27–1.32; Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 3 presents the results of the multiple regression analysis that estimates the simultaneous effects of study design, study quality, secular trend and tobacco industry affiliation. Controlling for the other variables, on the average case-control studies tended to yield lower risk estimates than cohort studies (by −.27, P=.075). Study quality, measured by the impact factor of the journal in which the paper was published, was not associated with the magnitude of the risk estimate (P=.828) . There was a secular trend in risk estimates, with the newer studies showing higher risks (increasing at 0.031/year, P=.020). Controlling for these other factors, affiliation with the tobacco industry was associated with significantly lower risk estimates, by −.37 (P=.008). Controlling for these other factors, this analysis indicates that the average risk of AD based on a non-industry affiliated cohort study in 2007 is 1.72 (P<.0005, the constant in the regression equation). All the variance inflation factors were 1.39 or less, indicating that these different factors were independent of each other.

Systematic Reviews

Ten systematic reviews of the association between smoking and AD were published between 1992 and 2008 (Table 4); 4 had tobacco industry affiliated authors. The association between author affiliation with the tobacco industry and the conclusion of their review was significant (P=0.005). Among the 6 reviews without tobacco industry affiliation, 1 found “no clear effect,” [9] 2 found “no protective effect” of smoking for AD,[5, 18] and 3 found smoking to be a significant risk factor for AD.[6–8] The 4 reviews with known tobacco industry affiliation concluded that smoking “protected against AD.”[10–13]

Table 4.

Reviews Of Smoking And Alzheimer’s Disease Reviews And Tobacco

| Author and Date |

Conclusion | Protective Effect |

Tobacco industry Affiliation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graves, A.B., van Duijn, C.M., et al., 1991[10] | “A statistically significant inverse association between smoking and Alzheimer’s disease was observed at all levels of analysis, with a trend towards decreasing risk with increasing consumption.” | Yes | Graves was a co-PI with Friedland funded by PM[89, 90] |

| Smith, C.J. & Giacobini, E. 1992[12] | “…nicotine or nicotine-like compounds may be useful in the amelioration of the attention and memory deficits associated with AD.” | Yes | Smith was employed by RJR [116] and Giacobini funded by RJR[117, 118] |

| Van Duijn, C.M., et al., 1994[13] | “… the odds ratio associated with family history of dementia tended to be lower for those with a positive smoking history…” | Yes | Graves[89, 90] co-PI with Friedland, funded by PM and Fratiglioni[99] co-PI with Winblad, funded by Swedish Tobacco Co. |

| Lee, P.N., 1994[11] | “… the negative association is consistent with other data suggesting nicotine protects against AD.” | Yes | Lee was a long term statistical consultant for the tobacco industry.[117, 119, 120] |

| Fratiglioni, L. & Wang, H., 2000[9] | “…a negative association for AD is controversial…not a clear effect” | Ambiguous | No* |

| Turner, C. & Spilich, G.J., 1997[18] | “ Scientists acknowledging tobacco industry support reported typically that nicotine or smoking improved cognitive performance while researchers not reporting the financial support of the tobacco industry were more nearly split on their conclusions.” | Ambiguous | No |

| Almeida, O.P., et al., 2001[5] | “Case-control and cohort studies produce conflicting results as to the direction of the association between smoking and AD.” | Ambiguous | No |

| Anstey, K.A., et al., 2007[6] | “elderly smokers have increased risks of dementia and cognitive decline”. | No | No |

| Hernan, M.A., et al., 2008[7] | “…selection bias due to censoring by death may be the main explanation for the reversal of the relative rate with increasing age.” | No | No |

| Purnell, C., et al., 2008[8] | “…four separate studies reported on the effect of smoking on incident AD. Three studies…reported that current smoking increased the risk of incident AD…an additional article…recorded only smoking and found that it was not significant.” | No | No |

Fratiglioni and Wang were research associates with Winblad, funded by Swedish Tobacco Co. 15 years earlier,[99] which we considered long enough ago to consider no Tobacco Affliliation for this review.

DISCUSSION

Controlling for study design, quality, secular trend and tobacco industry affiliation, we found a significant increase in AD risk associated with smoking. Controlling for all these factors, current or ever tobacco smoking was a significant risk factor for AD (RR= 1.72; 95% CI 1.33–2.12 for cohort studies of average quality in 2007). Case-control studies tended to yield lower risks than cohort studies and most of the tobacco affiliated studies used case-control design. Even after controlling for study design, tobacco industry affiliation was independently associated with lower risk estimates. In contrast to the significant increase in risk of AD that our analysis demonstrated, the combination of case-control design and tobacco industry affiliation yielded a protective odds ratio of 0.86 (95% CI 0.75–0.98).

The need to account for these factors in evaluating the evidence is demonstrated by the fact that if one simply combined all 43 studies in a single random effects meta-analysis, one would obtain an inaccurate null result (risk ratio = 1.05; 95% CI 0.91–1.20).

In 1992, Hirayama et al.[51] (no tobacco affiliation), published the first large cohort study and found smoking to be a risk factor for AD (RR = 1.61; 95% CI 1.10–2.38). In reference to Hiriyama’s soon to be published paper, PN Lee a long-time, paid statistical consultant for the tobacco industry,[52–54] informed Philip Morris Tobacco Company in a secret report, that “prospective studies are often more scientifically valid than case-control studies.”[55] However, Philip Morris continued to fund case-control studies and in 1994, RJR Biological Research Division initiated a project to investigate the “Utility and Feasibility of Funding Epidemiology Studies on smoking and Alzheimer’s Disease.”[56] This project included a review of current literature and several interviews with tobacco industry affiliated scientists. The recommendation from this project was that, it was no longer “feasible… to fund either a prospective or retrospective epidemiology study on cigarette smoking and AD.”[56]

In an earlier review of AD and smoking studies, cohort designs were found to be less susceptible to bias than case-control designs.[57] A potential problem with case-control studies is recall bias. AD patients all have memory deficits and reports given by proxy are often used to obtain smoking history. However, if proxy reports are not used for the control subjects as well, then bias can result.[57] Differential mortality is a problem when investigating the effects of smoking in Alzheimer’s disease because of the very low incidence rates of AD before age 75.[58] Persons with AD often die more quickly and are unavailable for case-control studies, which may lead to the false interpretation that smoking among cases is less common than it actually is and that smoking among control subjects is more common than among cases. Cohort studies often involve only a short time period of only 3–5 years, whereas, case control studies may cover activities over a period of decades. Debanne et al.[59] conducted a simulation study that showed that cohort studies also understate the risk of AD in smokers because of early deaths. (They did not compare the magnitude of the bias in cohort vs. case-control studies.) When survival among persons with the disease is related to the exposure of interest, downward bias can result.[57]

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. The primary data collector (JKC) was not blinded. The data extracted, however, were objective (i.e., risk ratios). In a study of blinding in 5 meta-analyses, blinding made no difference in the pooled risk estimates.[60]

In the document search for tobacco industry affiliation, we may not have retrieved every relevant document. Some materials may have been destroyed or concealed by the tobacco companies.[61] After 1998, the tobacco companies were aware that documents might eventually be made public and became more careful about what they wrote down.[62]

The application of meta-analysis to observational studies can be problematic because of biases in both the original studies and publication bias.[57, 63, 64] There is, however, no evidence of publication bias in the studies we considered (Figure 2).

Random effects meta-analysis is considered the appropriate approach for estimating risks when there are heterogeneous results among studies,[50] but does not explain the reasons for this heterogeneity. By dividing the studies according to design type (case-control or cohort) and whether or not there was tobacco industry affiliation, we found both groups of case-control studies to be homogenous. Both groups of cohort studies remained heterogeneous (albeit less so); we did not explore the reasons for heterogeneity within these subsets of studies. Study design type, industry affiliation and year of publication explained a significant portion of the heterogeneity among the 43 studies.

There was a nonsignificant trend toward lower risk estimates being associated with case-control studies (which yield ORs) than cohort studies (which yield RRs). The OR is an estimate of the RR when the RR is near 1.0; to the extent that the ORs from the case-control studies are not good estimates of the RR, this coefficient in the regression model (Table 3) quantifies the net effect of differences in results due to study design and biases due to using the OR as an estimate of RR.

One should interpret this significant association between conclusions of systematic reviews and tobacco industry affiliation cautiously. In the individual studies there is a secular trend in publishing, type of design, and tobacco industry funding, which may be confounded in this analysis of the reviews. There is a clear time trend in the publishing of case-control and cohort studies, with more of the former appearing in earlier years. Specifically, of the 26 case-control studies in Table 1, 23% were published in the 1980s, 58% in the 1990s, and 19% in the 2000s. In contrast, of the 17 cohort studies in Table 2, 6% were published in the 1980s, 41% in the 1990s, and 53% in the 2000s. It could be possible that the year of publication is associated with the conclusion of a reduction in AD risk for smokers, since all the industry-affiliated reviews were published in 1994 or earlier. This finding may be also be due to the fact that the tobacco industry stopped supporting reviews after 1994, as the cohort studies were beginning to appear.[56]

Conclusion

For the last two decades, the tobacco industry has been actively funding research that supports the position that cigarette smoking protects against AD, and for the past two decades, the scientific literature has reported conflicting results as to the direction of the association between smoking and AD. Consequently, older smokers and their health care providers have been unaware that smoking is a modifiable risk factor for AD. There is an association between tobacco industry affiliation and the conclusions of individual studies and, probably, review papers of AD. Controlling for industry affiliation, study design and other factors, smoking is not protective against AD; it is a significant and substantial risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Funding/Support: This research was supported by the California Tobacco Related Disease Research Program grant no. 16RT-0149; National Cancer Institute grant no. CA-87472 and National Institute Drug Addiction K23-DA018691.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding agencies had no role in the design of the study, the conduct of the research, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Cataldo had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Cataldo, Prochaska, Glantz.

Acquisition of data: Cataldo.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Cataldo, Prochaska, Glantz.

Drafting of the manuscript: Cataldo, Prochaska, Glantz.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Cataldo, Prochaska, Glantz.

Statistical analysis: Glantz

Obtained funding: Cataldo, Prochaska, Glantz.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Cataldo, Prochaska, Glantz.

Study supervision: Cataldo, Prochaska, Glantz.

Financial Disclosures: None reported.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of NCI, California TRDRP or NIDA

Additional Contributions: None.

References

- 1.Brookmeyer R. Forecasting the global prevalence and burden of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2007;3:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.04.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meyer JS, Rauch GM, Rauch RA, Haque A, Crawford K. Cardiovascular and other risk factors for Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Annal N Y Acad Science. 2000;903:411–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bazzano LA, He J, Muntner P, Vupputuri S, Whelton PK. Relationship between cigarette smoking and novel risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:891–897. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-11-200306030-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ockene IS, Miller NH. Cigarette smoking, cardiovascular disease, and stroke a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1997;96:3243–3247. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Almeida OP, Hulse GK, Lawrence D, Flicker L. Smoking as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease: contrasting evidence from a systematic review of case-control and cohort studies. Addiction. 2002;97:15–28. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anstey KJ, von Sanden C, Salim A, O'Kearney R. Smoking as a risk factor for dementia and cognitive decline: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:367–378. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hernan MA, Alonso A, Logroscino G. Cigarette smoking and dementia: potential bias in the elderly. Epidemiology. 2008;19:448–450. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816bbe14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Purnell C, Gao S, Callahan CM, Hendrie HC. Cardiovascular risk factors and incident Alzheimer disease. Alz Dis Assoc Dis. 2008 doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318187541c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fratiglioni L, Wang HX. Smoking and Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease: review of the epidemiological studies. Behav Brain Res. 2000;113:117–120. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(00)00206-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graves AB EURODEM Risk Factors Research Group. Alcohol and tobacco consumption as risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: a collaborative re-analysis of case-control studies. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:48–57. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.supplement_2.s48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee PN. Smoking and Alzheimer's disease: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Environ Tech Lett. 1994;13:131–144. doi: 10.1159/000110372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith CJ, Giacobini E. Nicotine, Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease. Rev. Neurosci. 1992;3:25–43. doi: 10.1515/REVNEURO.1992.3.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Duijn CM, Clayton DG, Chandra V, Fratiglioni L, Graves AB, Heyman A, Jorm AF, Kokmen E, Kondo K, Mortimer JA EURODEM Risk Factors Research Group. Interaction between genetic and environmental risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: a reanalysis of case-control studies. Genet Epidemiol. 1994;11:539–551. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370110609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen GB, Payne TJ, Lou XY, Ma JZ, Zhu J, Li MD. Association of amyloid precursor protein-binding protein, family B, member 1 with nicotine dependence in African and European American smokers. Hum Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00439-008-0558-9. ISSN 0340-6717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alzheimer's Association. [September 16, 2008,Accessed];Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. www.alz.org/national/documents/report_alzfactsfigures2008.pdf.

- 16.Barr N. Oprah Magazine. Harpo, Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cataldo JK. Clinical implications of smoking and aging: breaking through the barriers. J Gerontol Nurs. 2007;33:32–41. doi: 10.3928/00989134-20070801-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner C, Spilich GJ. Research into smoking or nicotine and human cognitive performance: does the source of funding make a difference? Addiction. 1997;92:1423–1426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Biomedical Research Contributions 00 1976. RJ Reynolds: http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/nfw92d00. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seitz F. [06 Aug 1981];RJ Reynolds: Report on R. J. Reynolds Research Grants Program. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/njs65d00.

- 21.Carchman RA. Case Western. Philip Morris: [29 Sep 1993]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xzn87e00. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carchman RA. Proposed Alzheimers' Study Status. Philip Morris: [24 Sep 1990]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tpc58e00. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ford D. Site visit to Dr. L. Barclay at the Burke Rehabilitation Center, White Plains, New York, February 20, 1987 site visitors: Drs. D.H. Ford and H. McAllister grant no. 1965 Tobacco use in relation to Alzheimer's disease 00 1987. Council for Tobacco Research. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gfb79c00.

- 24.Appel SH. Alzheimer's Disease. In: Enna SJ, editor. Brain neurotransmitters and receptors in aging and age related disorders. New York City: Raven Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 25. [09 Feb 1988];RJ Reynolds: Status Report on Key R&D Programs Year-End. 1987 (870000) http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gtx54d00.

- 26.Glantz SA, Slade J, Bero LA, Hanauer P, Barnes D. The cigarette papers. Berkeley: The University of California Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bero LA. Tobacco industry manipulation of research. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:200–208. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bero LA, Glantz S, Hong MK. The limits of competing interest disclosures. Tob Control. 2005;14:118–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bekelman JE, Li Y, Gross CP. Scope and impact of financial conflicts of interest in biomedical research: a systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289:454–465. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barnes DE, Bero LA. Why review articles on the health effects of passive smoking reach different conclusions. JAMA. 1998;279:1566–1570. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scollo M, Lal A, Hyland A, Glantz S. Review of the quality of studies on the economic effects of smoke-free policies on the hospitality industry. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:13–20. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cho MK, Bero LA. The quality of drug studies published in symposium proceedings. Ann Int Med. 1996;124:485–489. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-5-199603010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B, Clark O. Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. Brit Med J. 2003;326:1167–1170. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swaen GM, Meijers JM. Influence of design characteristics on the outcome of retrospective cohort studies. Brit J Ind Med. 1988;45:624–629. doi: 10.1136/oem.45.9.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bowirrat A, Treves TA, Friedland RP, Korczyn AD. Prevalence of Alzheimer's type dementia in an elderly Arab population. Eur J Epidemiol. 2001;8:119–123. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2001.00183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grossberg GT, Nakra R, Woodward V, Russell T. Smoking as a risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. J AM Geriat Soc. 1989;37:819. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1989.tb02247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salib E. Risk factors in clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease: a retrospective hospital-based case control study in Warrington. Aging & Mental Health. 2000;4:259–267. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salib E, Hillier V. A case-control study of smoking and Alzheimer's Disease. Int J Geriat Psychiat. 1997;12:295–300. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199703)12:3<295::aid-gps476>3.3.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reitz C, den Heijer T, van Duijn C, Hofman A, Breteler MMB. Relation between smoking and risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2007;69:998–1105. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271395.29695.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ott A, Slooter AJ, Hofman A, van Harskamp F, Witteman JC, Van Broeckhoven C, van Duijn CM, Breteler MM. Smoking and risk of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in a population-based cohort study: the Rotterdam Study. Lancet. 1998;351:1840–1843. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(97)07541-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindsay J. Risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: a prospective analysis from the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:445–453. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Andel R. The Canadian Study of Health and Aging: risk factors for Alzheimer's disease in Canada. Neurology. 1994;44:2073–2080. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.11.2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tyas SL. Alcohol Use and the Risk of Developing Alzheimer's Disease. 2001;25:299–307. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tyas SL, Koval JJ, Pederson LL. Does an interaction between smoking and drinking influence the risk of Alzheimer’s disease? Results from three Canadian data sets. Stat Med. 2000;19:1685–1696. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000615/30)19:11/12<1685::aid-sim454>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bachman DL, Green RC, Benke KS, Cupples LA, Farrer LA. Comparison of Alzheimer's disease risk factors in white and African American families. Neurology. 2003;60:1372–1374. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000058751.43033.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harwood DG, Barker WW, Loewenstein DA, Ownby RL, St. George-Hyslop P, Mullan M, Duara R. A cross-ethnic analysis of risk factors for AD in white Hispanics and white non-Hispanics. Neurology. 1999;52:551–551. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.3.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang HX, Fratiglioni L, Frisoni GB, Viitanen M, Winblad B. Smoking and the Occurrence of Alzheimer's Disease: Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Data in a Population-based Study. Amer J Epidemiol. 1999;149:640–644. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bero L. Implications of the tobacco industry documents for public health and policy. Annu Rev Publ Health. 2003;24:267–288. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.24.100901.140813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Malone RE, Balbach ED. Tobacco industry documents: treasure trove or quagmire? Tob Control. 2000;9:334–338. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Jones DR, Sheldon TA, Song F. Methods for Meta-Analysis in Medical Research. New York: Wiley; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hirayama T. Large cohort study on the relation between cigarette smoking and senile dementia without cerebrovascular lesions. Brit Med J. 1992;1:176. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee PN. [08 Oct 1982];Philip Morris: Reanalysis of Prof. V.M. Hawthorne's Data Some Comments on the Report by Liesi Hebert and John Fry (Td 1659) http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xhj32e00.

- 53.Lee PN. Misclassification of Smoking Habits and Its Relevance to the Observed Relationship between Passive Smoking and Lung Cancer a Review of the Evidence. Philip Morris: [04 Jun 1987]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aoy68e00. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee PN. [00 Feb 1995];Philip Morris: Subject Index of Reviewed Papers on Smoking and Health from 780000. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/crg22d00.

- 55.Lee PN. Brit Med J. Vol. 302. Philip Morris: [12 Aug 1991]. Subject Ref 18a 'Relation between Nicotine Intake and Alzheimer's Disease Cm Van Duijn and a Hofman; pp. 1491–1494. (910000) http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hcu34e00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Biological Research and Debethizy JD. RDM CJS94 001. [06 Jan 1994];RJ Reynolds: Utility and Feasibility of Funding Epidemiology Studies on Smoking and Alzheimer's Disease (Ad) http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wex53d00.

- 57.Kukull WA. The association between smoking and Alzheimer’s disease: effects of study design and bias. Biol Psychiat. 2001;49:194–199. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)01077-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wolf-Klein GP, Silverstone FA, Brod MS, Levy A, Folety C, Termotto V, Breuer J. Are Alzheimer patients healthier? J Amer Geriat Soc. 1988;36:219–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1988.tb01804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Debanne S, Bielefeld R, Cheruvu V, Fritsch T, Rowland D. Alzheimer's disease and smoking: bias in cohort studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11:313–321. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Berlin JA. Does blinding of readers affect the results of meta-analyses? Lancet. 1997;350:185–186. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)62352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liberman J. The shredding of BAT's defense: McCabe v British American Tobacco. Aust Tob Control. 2002;11:271–274. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.3.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.LeGresley E, Muggli M, Hurt R. Playing hideandseek with the tobacco industry. Nicotine Tob Research. 2005;7:27–40. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331328529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blettner M, Sauerbrei W, Schlehofer B, Scheuchenpflug T, Friedenreich C. Traditional reviews, meta-analyses and pooled analyses in epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1999;28:1–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/28.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology A Proposal for Reporting. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–2012. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Amaducci LA. Risk factors for clinically diagnosed Alzheimer's disease: a case-control study of an Italian population. Neurology. 1986;36:922–931. doi: 10.1212/wnl.36.7.922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brenner DE. Relationship between cigarette smoking and Alzheimer's disease in a population-based case-control study. Neurology. 1993;43:293–300. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Broe GA. A case-control study of Alzheimer's disease in Australia. Neurology. 1990;40:1698–1707. doi: 10.1212/wnl.40.11.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chandra V. Case-control study of late onset" probable Alzheimer's disease". Neurology. 1987;37:1295–1300. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.8.1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Debanne SM, Rowland DY, Riedel TM, Cleves MA. Association of Alzheimer's disease and smoking: the case for sibling controls. J Amer Geriat Soc. 2000;48:800–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ferini-Strambi I, Smirne S, Garancini P, Pinto P, Franceschi M. Clinical and epidemiological aspects of Alzheimer's disease with presenile onset: a case control study. Neuroepidemiology. 1990;9:39–49. doi: 10.1159/000110750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Forster DP, Newens AJ, Kay DW, Edwardson JA. Risk factors in clinically diagnosed presenile dementia of the Alzheimer type: a case-control study in northern England. J Epidemiol Comm Health. 1995;49:253–258. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.3.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.French LR, Schuman LM, Mortimer JA, Hutton JT, Boatman RA, Christians B. A case-control study of dementia of the Alzheimer type. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;121:414–421. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heyman A, Wilkinson WE, Stafford JA, Helms MJ, Sigmon AH, Weinberg T. Alzheimer's disease: A study of epidemiological aspects. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:335–341. doi: 10.1002/ana.410150406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Maia L, de Mendonca A. Does caffeine intake protect from Alzheimer's disease? Eur J Neurol. 2002;9:377–382. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2002.00421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prince M. Risk factors for Alzheimer's disease and dementia: a case-control study based on the MRC elderly hypertension trial. Neurology. 1994;44:97–104. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shaji S, Promodu K, Abraham T, Roy KJ, Verghese A. An epidemiological study of dementia in a rural community in Kerala, India. Brit J Psychiat. 1996;168:745. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.6.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shalat SL, Seltzer B, Pidcock C, Baker E. Risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: A case-control study. Neurology. 1987;37:1630–1633. doi: 10.1212/wnl.37.10.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.van Duijn CM, Hofman A. Relation between nicotine intake and Alzheimer's disease. Brit Med J. 1991;302:1491–1494. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6791.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wang PN, Wang SJ, Hong CJ, Liu TT, Fuh JL, Chi CW, Liu CY, Liu HC. Risk factors for Alzheimer's disease: a case-control study. Neuroepidemiology. 1997;16:234–240. doi: 10.1159/000109692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Friedland RP. Philip Morris: [07 Feb 2000]. R582 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pir17d00. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Friedland RP, Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Debanne SM, Lerner AJ MIRAGE Study Group. Smoking and risk of Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1998;352:819. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)60714-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Friedland RP, Fritsch T, Smyth KA, Koss E, Lerner AJ, Chen CH, Petot GJ, Debanne SM. Patients with Alzheimer's disease have reduced activities in midlife compared with healthy control-group members. Arch Neurol. 2001;60:753–759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061002998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Barclay LBRC. [27 Dec 1985];Council for Tobacco Research. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/geb79c00.

- 84.Information Required for Drawing and Mailing of CTR Grant Checks. 00 1900. Council for Tobacco Research. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tcb79c00.

- 85.Gertenbach RFCTR. [10 Mar 1986];Council for Tobacco Research. Grant No. 1965. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tdb79c00.

- 86.Bowirrat A, Chapman J, Friedland RP, Hofman A, Iqbal K, Korczyn AD, Snider A, Swaab DF, Treves T, Winblad B, Wisniewski HM. The 6th International Conference on Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders. Philip Morris: Alzheimer's Disease Prevalence Is High in Israeli Arabs. 00 1998. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yhs34a00.

- 87.Philip Morris: Budget Justification Molecular and Cultural Epidemiology of Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders: Israel - Cleveland Collaborative Studies. 00 1997. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/iot08d00.

- 88.Graves AB, White E, Koepsell TD, Reifler BV, van Belle G, Larson EB, Raskind M. A case-control study of Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:766–774. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. [21 Mar 1996];Philip Morris: Molecular and Cultural Epidemiology of Ad and Related Disorder: Israel - Cleveland Collaborative Studies. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aem13e00.

- 90.Graves AB. Philip Morris: [20 Mar 1996]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cem13e00. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lerner A, Koss E, Debanne S, Rowland D, Smyth K, Friedland R. Smoking and oestrogen-replacement therapy as protective factors for Alzheimer's disease. Lancet. 1997;349:403–404. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)80025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Philip Morris: [18 Jun 1997]. R582. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ouq17d00. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Budget Justification the CWRU- AD Case-Control Study. Philip Morris: 00 1997. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lot08d00. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Plassman BL, Helms MJ, Welsh KA, Saunders AM, Breitner JC. Smoking, Alzheimer's disease, and confounding with genes. Lancet. 1995;345:387. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)90374-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Contract Information. RJ Reynolds: [20 Dec 1993]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wwg92d00. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Duke U, Levin ED. [16 Dec 1993];RJ Reynolds: Analysis of the Interactions of Smoking and Alzheimer's Disease. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ywg92d00.

- 97.Friedland RP. Philip Morris: [29 Jan 1993]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qci48e00. [Google Scholar]

- 98.RJR, Ehmann CW, Rjhn I, Levin ED, Snyderman R, Duke U. Described in the Basic Research Proposals Entitled "Analysis of the Interactions of Smoking and Alzheimer's Disease", "Use of Transdermal Nicotine for Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease", and "Critical Sites of Action for Nicotine-Induced Cognitive Improvement". RJ Reynolds: [16 Dec 1993]. This Will Confirm to You That R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company ("Reynolds") Will Support Nicotine Research Which You Are Conducting, through a Gift to Duke University Medical Center (the "Institition") http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xwg92d00. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nordberg AUU, Winblad BUU, Neuroscience L. Reduced Number of (3h) Nicotine and (3h) Acetylcholine Binding Sites in the Frontal Cortex of Alzheimer Brains. Council for Tobacco Research. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90629-4. 00 1986. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fxw46d00. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 100.Aggarwal NT, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Wilson RS, Morris MC, Schneider JA, Shah RC, Evans DA. The Relation of Cigarette Smoking to Incident Alzheimer's Disease in a Biracial Urban Community Population. Neuroepidemiology. 2006;26:140–146. doi: 10.1159/000091654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Broe GA, Creasey H, Jorm AF, Bennett HP, Casey B, Waite LM, Grayson DA, Cullen J. Health habits and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia in old age: a prospective study on the effects of exercise, smoking and alcohol consumption. Aust New Zeal J Publ Health. 1998;22:621–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.1998.tb01449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Doll R. Smoking and dementia in male British doctors: prospective study. BMJ. 2000;320:1097–1102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7242.1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Juan D, Zhou DHD, Li J, Wang JYJ, Gao C, Chen M. A 2-year follow-up study of cigarette smoking and risk of dementia. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:277–282. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-1331.2003.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Launer LJ, Andersen K, Dewey ME, Letenneur L, Ott A, Amaducci LA, Brayne C, Copeland JRM, Dartigues JF, Kragh-Sorensen P. Rates and risk factors for dementia and Alzheimer's disease: results from EURODEM pooled analyses. Neurology. 1999;52:78–84. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Laurin D, Masaki KH, Foley DJ, White LR, Launer LJ. Midlife dietary intake of antioxidants and risk of late-life incident dementia: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:959–967. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Luchsinger JA, Reitz C, Honig LS, Tang MX, Shea S, Mayeux R. Aggregation of vascular risk factors and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65:545–551. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000172914.08967.dc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Merchant C, Tang MX, Albert S, Manly J, Stern Y, Mayeux R. The influence of smoking on the risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1999;52:1408–1412. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.7.1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Moffat SD, Zonderman AB, Metter EJ, Kawas C, Blackman MR, Harman SM, Resnick SM. Free testosterone and risk for Alzheimer disease in older men. Neurology. 2004;62:188–193. doi: 10.1212/wnl.62.2.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Piguet O, Grayson DA, Creasey H, Bennett HP, Brooks WS, Waite LM, Broe GA. Vascular Risk Factors, Cognition and Dementia Incidence over 6 Years in the Sydney Older Persons Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22:165–171. doi: 10.1159/000069886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yoshitake T. Incidence and risk factors of vascular dementia and Alzheimer's disease in a defined elderly Japanese population: the Hisayama Study. Neurology. 1995;45:1161–1168. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.6.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Beckett LA, Funkenstein HH, Albert MS, Chown MJ, Evans DA. Relation of Smoking and Alcohol Consumption to Incident Alzheimer's Disease. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:347–355. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Katzman R, Aronson M, Fuld P, Kawas C, Brown T, Morgenstern H, Frishman W, Gidez L, Eder H, Ooi WL. Development of dementing illnesses in an 80-yearold volunteer cohort. Ann Neurol. 1989;25:317–324. doi: 10.1002/ana.410250402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Smith CJ, RJR . Conversation with Dr. Robert Katzman. RJ Reynolds: 1987. May 25, [27 May 1987]. (870525). http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sxu63d00. [Google Scholar]

- 114.Stone D. Council for Tobacco Research. [29 Dec 1986]. Grant Application #2134 J. G. Joshi, Ph.D. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/atr00d00. [Google Scholar]

- 115.Stone D. Council for Tobacco Research. [02 Feb 1987]. Grant Application #2134 J.D. Joshi, Ph.D. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xsr00d00. [Google Scholar]

- 116.Smith C, Simmons S Smoking and Health DIV. Rdm87 1. [07 Oct 1987];RJ Reynolds: Nicotine and Alzheimer's Disease. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/les03a00.

- 117.Funding Levels. RJ Reynolds: 1992. [02 Aug 1991]. Extramural Nicotine Research Proposed. (920000 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ifz53d00. [Google Scholar]

- 118.RJ Reynolds: Smoking & Health Contract Research Program. 00 1989. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fnf97c00.

- 119.Consultancy - PN Lee. Philip Morris: [00 Oct 1993]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sej14e00. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lee PN. Current and Recent Activities. Philip Morris: [13 Oct 1994]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tlx85e00. [Google Scholar]