Roman Catholic Parishes

Essay

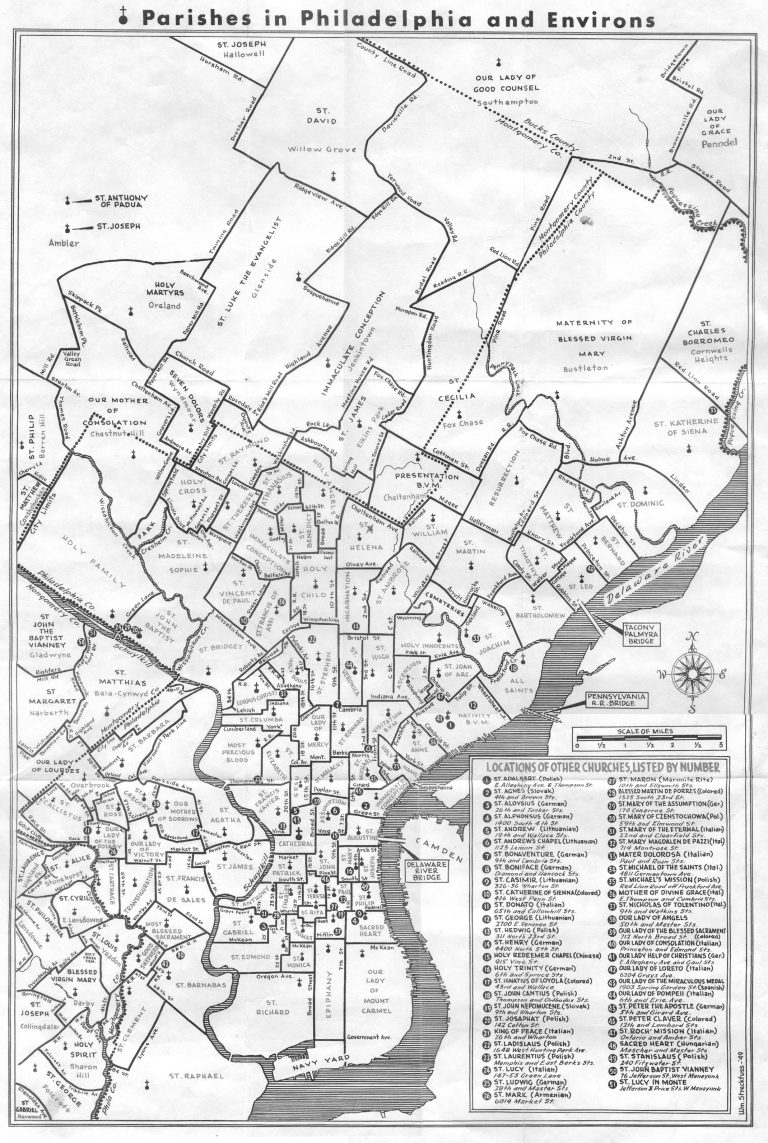

Parishes stand at the center of Roman Catholic religious life. Since the arrival of Catholicism in the Philadelphia region in the early eighteenth century, parishes have shaped Catholics’ sense of communal identity by functioning as both the administrative unit of a diocese and the primary site of Catholic worship. Developing into expansive complexes that often included a rectory, school, convent, and church, parishes reflected a considerable commitment of spiritual and financial resources. Many Catholics understood the region’s geography in terms of parish lines, and churches became among the most visible neighborhood landmarks.

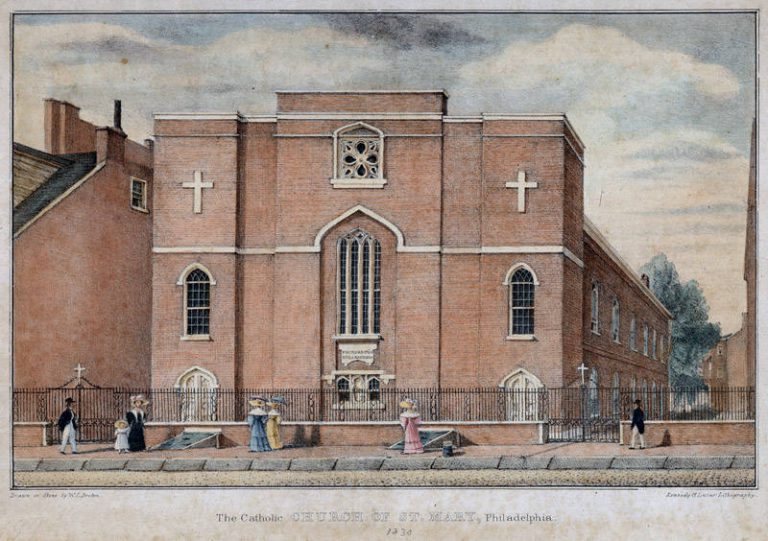

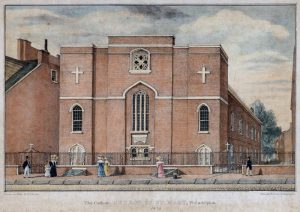

The foundations of Catholic parish life in the Philadelphia region date back to the establishment of Old St. Joseph’s Church (321 Willings Alley) in 1733. At the time, it was the only place in the English colonies where Catholics could worship openly as a community rather than having to hold religious services in homes and private chapels. It also provided a home base for circuit-riding priests who served mission stations scattered throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and the mid-Atlantic region. As the Catholic population of Philadelphia grew, Catholics constructed a second church, St. Mary’s (252 S. Fourth Street), one block away from Old St. Joseph’s, in 1763. By the time of the establishment of the Philadelphia Diocese in 1808, the number of churches in the city had doubled to four, with an additional twelve located across its territory, which at the time encompassed Pennsylvania, Delaware, and southern New Jersey.

American independence provided Catholics with greater freedom to establish parishes, but the new political climate also resulted in administrative tensions that discouraged bishops from doing so. In the post-Revolutionary period, some members of the Catholic community challenged church authority by demanding that the laity be given a formal role in parish governance, just as their Protestant peers enjoyed within their congregations. This led to a series of disputes within local parishes over what came to be known as “trusteeism,” the most prominent of which took place in the 1820s at Old St. Mary’s, where a schism occurred when a faction took control of the church to protest the bishop’s removal of a popular priest. In the wake of these controversies, the Vatican and the U.S. courts upheld the authority of the bishop and his appointed clergy over parishes and their property.

The Brick-and-Mortar Era

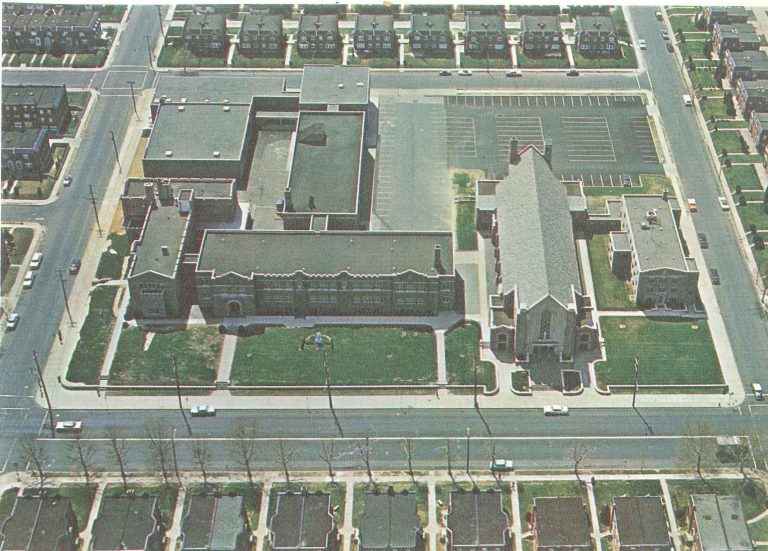

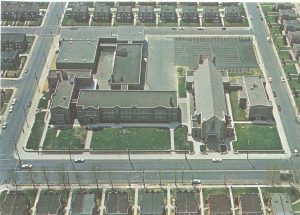

Parish growth in the Philadelphia region accelerated dramatically during the middle decades of the nineteenth century in response to urban expansion and the influx of Irish and German immigrants. It continued apace during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries as Philadelphia’s immigrant ranks swelled with arrivals from Eastern and Southern Europe and population growth led to the development of new residential districts in and around the city. During this era of “brick-and-mortar” Catholicism, church officials often proved remarkably savvy in brokering real estate deals and marshaling the funds needed to complete ambitious building projects. Church spires rose over neighborhoods and parish plants sprawled over entire city blocks.

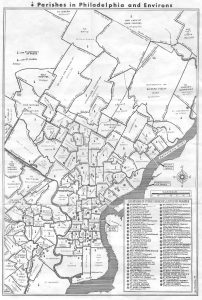

To manage this extensive parish growth, church leaders in Philadelphia and the surrounding region maintained a system of strict parish boundaries. As soon as a parish was established, the bishop formally defined its territorial geography in relation to neighboring parishes. Catholics were expected to register with the parish within whose boundaries they lived, receive the sacraments there, and send their children to that parish’s school. The parish, likewise, had to maintain registers for dates of baptism, first communion, marriage, and other rites of passage for all who lived within its boundaries. The system served a number of purposes, including eliminating competition among parishes and their clergy and committing individuals to support their local parish financially. It also helped keep Catholics rooted in their neighborhoods since moving even a few blocks could require a transfer of parish membership.

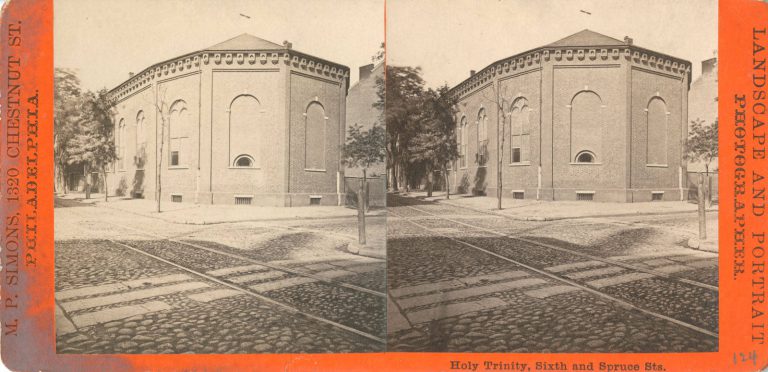

Interspersed among these territorial parishes, “national” parishes served particular ethnic, racial, or linguistic communities. Philadelphia became home to the first such national parish in the United States in 1789, with the establishment of Holy Trinity to serve the city’s German-speaking community. Philadelphia likewise became home to the first Italian national parish in the country, St. Mary Magdalene de Pazzi, in South Philadelphia, founded in 1852. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, national parishes became the model for dealing with diversity within the U.S. church, with the system expanding to include national parishes for the Polish, Lithuanian, Bohemian, Chinese, and African American communities, among others. This overlay of territorial and national parishes accounts for the density of parishes in some Philadelphia neighborhoods, such as Port Richmond, where several churches stood in the shadow of one another.

Responsive to the diverse needs of their members, parishes developed into hubs of spiritual and social activity. To encourage religious practice and deepen spiritual ties to the parish, church leaders sponsored preaching missions, organized devotional groups known as sodalities, and incorporated popular devotions into the life of the parish. Among them, the practice of Eucharistic adoration services known as “Forty Hours” at each parish throughout the diocese became popular in Philadelphia starting in the 1850s before spreading nationally. Parishes also sponsored sports teams and musical groups, held dances and other social events, and provided a range of outreach services. Recognizing the importance that Catholics placed on parish membership and involvement, real estate and rental listings often identified the location of properties by the name of the local parish, and a number of parishes even sponsored building and loan societies to promote investment in the community.

The strength of parish life in Philadelphia and the surrounding region from the mid-nineteenth century onward was intimately connected to the development of the parochial school system. Starting in the 1850s under Bishop John Neumann (1811-60), in response to anti-Catholic, nativist hostility and the needs of an immigrant population, parishes were encouraged to establish schools to provide catechetical instruction and protect children from real and perceived anti-Catholic influence within the public schools. At the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore in 1884, the U.S. bishops officially declared that every parish in the country with the means to do so should operate its own school. This decision spurred the massive expansion of the parochial school system in Philadelphia and elsewhere. In some instances, parishes prioritized the construction of the school building over the church itself, anticipating that the school would help draw families to the parish. The sponsorship of schools also strengthened the role of the parish as the center of Catholic family life and increased youth activity within the parish.

Restructuring and Renewal

Although the baby boom and the rapid suburbanization of the post-World War II years spurred the creation of new parishes and the physical expansion of existing ones, many older parishes struggled to adjust to changing circumstances. Since the 1970s, demographic shifts, declining church attendance, the high cost of maintaining aging sanctuaries, and a shortage of priests have all contributed to the consolidation and closure of parishes throughout the region. It was not until 1993, however, that the Archdiocese of Philadelphia implemented its first major restructuring plan and significantly reduced the number of parishes in North Philadelphia and the city of Chester. Systematic pastoral planning designed to evaluate parishes’ spiritual and financial viability led to a steady stream of closures that reduced the number of parishes in the archdiocese from 302 in 1992 to 219 in 2015. Responding to similar pressures, the Diocese of Camden announced plans in 2008 to shrink the number of parishes by nearly half, from 124 to 66, over the course of two years. Although parishioners who felt that decisions were made without adequate consultation rarely succeeded in reversing decisions, their public outcries nevertheless reflected the strength of parish loyalty among Catholics as well as a wider community concern over the loss of Catholic parishes and its impact on neighborhoods.

Even as many parishes waned, new waves of immigration helped to revive and transform others. In the Philadelphia region’s cities and older suburban towns, an influx of Catholics from Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and Southeast Asia in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries brought new vitality to a number of parishes. Although the transition was not always welcomed by existing parishioners, it reflected a movement by church officials away from establishing new national parishes for various ethnic or linguistic communities in favor of encouraging different groups to worship within “shared” parishes. In addition, church leaders encouraged parish partnerships within regional clusters and the sharing of priestly personnel as ways of maintaining the continued viability and institutional presence of the region’s Roman Catholic parishes.

Thomas Rzeznik is an Associate Professor of History at Seton Hall University and co-editor of the quarterly journal American Catholic Studies. He is also author of Church and Estate: Religion and Wealth in Industrial Era Philadelphia (Penn State Press, 2013). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Can we call it a comeback for Philly Catholic schools? (WHYY, February 9, 2017)

- Catholic churches consolidate and close as population declines (WHYY, April 25, 2016)

- Century-old Catholic church in eastern Pennsylvania to close (WHYY, February 22, 2016)

- Catholic families find comfort, community in world meeting (WHYY, September 24, 2015)

- Catholic Archdiocese of Camden pushing for immigration reforms (WHYY, May 6, 2013)

Links

- Philadelphia Church Project

- The Memorial volume : a history of the third Plenary council of Baltimore, November 9-December 7, 1884 (Archive.org)

- The Gesu School Story (Crisis Magazine)

- PhilaPlace: St. Stanislaus Catholic Church (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: St. Mary Magdalen de Pazzi Roman Catholic Church (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Holy Redeemer Chinese Catholic Church (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Risen from the Ashes: St. Joseph’s Preparatory School and the Gesu Church, Part 1 (PhillyHistory Blog)