Horizontal Steam Engine Model

Artifact

Drag across the screen to turn the object. Zoom to view details.

Read more below.

Essay

Model of a horizontal steam engine, c. 1880, represents Philadelphia’s manufacturing prowess in the late nineteenth century. (Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent, gift of A. Atwater Kent, Photograph by Sara Hawken)

We know very little about this model of a horizontal steam engine, beyond the information that it conveys. Probably made in the late nineteenth century, it may have come out of a vocational training class. Or perhaps an apprentice machinist, training in a working shop, made the model to demonstrate his new-found skills. It models an engine used to drive factory machinery. Such “mill engines” typically had a foundation of brickwork; here the “brick” is actually made from wood.

In the Philadelphia of 1880, hundreds of shops and factories making everything from hats to locomotives had a full-sized engine, a larger version of this model, often hidden away in a basement. So its anonymity is appropriate. Also in the basement was a pile of anthracite coal, brought from northeast Pennsylvania through the Schuylkill Navigation canal or by the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, then delivered to shops and factories across the city by horse-drawn wagon. A boiler, fired by coal, produced steam which, piped to the engine, drove its cylinder and flywheel at fifty to 200 revolutions per minute. A continuous leather belt transferred the engine’s power to one or a dozen machines in the shop. Those lathes and presses, carding machines and textile looms, stamping mills and polishing machines were always tended by human workers – often quite skilled.

In thinking about machinery and industrial development, we often forget about the human element of the steam engine. Before steam power became widespread (before 1830), saw mills, gristmills, and textile factories required the water of falling rivers and streams to power waterwheels and water turbines. Therefore mills located in the countryside, where “waterpowers” were commonplace. Simple steam engines like this one brought a revolutionary change to the United States in the early nineteenth century, transforming cities into centers of manufacturing. With steam power, factories came to town, drawing from the expanding working classes of the city to produce a dazzling array of goods.

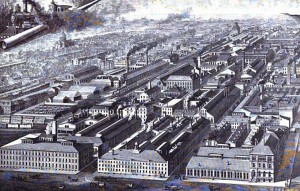

This combination of workers’ skills and effort, coupled to steam power, gave Philadelphia its proud claim as “workshop of the world.” In truth, New York City had more manufacturing jobs in the decades following the Civil War, alongside its strengths in finance, railways, and shipping. By contrast, Philadelphia focused on making the goods demanded by a nation embracing industrial and urban life. Along the Schuylkill River, and in pockets across the city, textile mills made everything from knitted hosiery to figured carpets. These firms often started out with waterpower from the river, then expanded over the years by adopting steam engines to drive looms. By 1882, the John B. Stetson Company in Kensington had grown to international renown, its 700 workers producing high quality hats in dozens of styles. Steam engines drove lines of production machinery that removed felt from animal skins, blowers to create felt mats, and box-making machines to package the finished product. In the Nicetown section, Midvale Steel made specialty steel castings and armor plate for the U.S. Navy. Specialized steam engines turned the plate rolls that produced the armor. Two famous companies, Bement & Dougherty and William Sellers & Co., made precision machine tools for railroads and metalworking plants across the country. Their own production of these complicated mechanisms drew equally on workers’ skills and production machinery driven by steam. At the Baldwin Locomotive Works in the 1880s, stationary engines powered metal lathes, boring machines, trip hammers – even a dynamo to make electricity for the new lights in the production shops. At all of these plants and hundreds of smaller shops across the city, the powered machines advanced three broad goals – bolstering overall output, improving product quality, or enabling entirely novel operations unknown in the pre-industrial world.

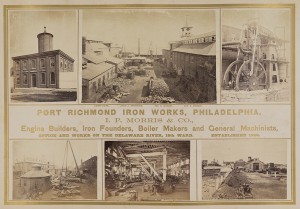

Philadelphia engine builders were also important to the city’s reputation. A basic mill engine like the model had fewer than a dozen moving parts, so small machine shops found them comparatively easy to make once the designs and techniques of machine building in iron spread after the 1820s. During the Gilded Age, some Philadelphia companies such as the Bush Hill Iron Works still made simple horizontal engines. But engineers and shop proprietors had learned over the century to craft much more sophisticated steam engines, bolstering efficiency and power output while customizing engines for specialized applications. In a sprawling factory in the Port Richmond neighborhood, I.P. Morris & Co. made custom blowing engines upwards of thirty feet tall, to create the continuous air blast needed to smelt steel in a Bessemer converter. I.P. Morris also did a good business building large pumping engines as cities across the country built out their systems of piped public water. On the Delaware River in the Kensington neighborhood, the Penn Steam Engine and Boiler Works made custom marine steam engines for the propeller-driven steamboats that were also a Philadelphia specialty.

Gilded Age makers of pumping engines or marine steam plants focused on improving efficiency and reliability. In particular, they adopted multi-cylinder engines that used steam first in a high-pressure cylinder, then reused it in adjacent cylinders at medium and low pressures. After 1880, such “compound” or “triple expansion” engines finally made steamships efficient enough to challenge sailing vessels in trans-oceanic freight. The economical engine designs developed for urban pumping stations in the 1880s were adapted a decade later to drive the new generating stations making electricity for city lighting and electric trolley services. From small beginnings came power supplies that enlarged city populations, turned night into day, and reached around the globe.

Text by John K. Brown, Associate Professor of History, University of Virginia, and author of The Baldwin Locomotive Works, 1831-1915: A Study in American Industrial Practice (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995).