World War I

By Jacob Downs

Essay

Although the United States’ military involvement in the First World War lasted just over a year, the conflict in Europe had a lasting impact on the Philadelphia region. The war created new opportunities for the industrial base of Philadelphia, Chester, and Camden, and as men and women enlisted for military service, the region developed a sense of a patriotic community through food drives and bond campaigns. World War I, known at the time as the Great War, also reshaped the region’s social landscape. African Americans migrated from the South in large numbers to fill industrial jobs, and women found new opportunities outside the home. However, the war also caused a serious backlash toward German Americans, one of the region’s earliest and long-lasting population groups.

As Europe became engulfed in a bitter war in 1914, most Philadelphians supported the position of neutrality proclaimed by President Woodrow Wilson. While the United States did not deploy combat troops in the early stages of the war, it did send munitions, weapons, textiles, and other goods to England and France. Philadelphia played a vital role in that supply.

In the Philadelphia region, the war in Europe sparked meetings, discussions, and public gatherings, and major events had local impact. For example, after local newspapers reported that German armies committed atrocities in Belgium in 1914, residents of Philadelphia and the surrounding area raised money for Belgian relief. In May 1915, twenty-seven Philadelphians died when a German U2 boat torpedoed and sank the British ocean liner Lusitania. Eight of them were members of the family of Paul Crompton (1871-1915), vice president of the Surpass Leather Company in Northwest Philadelphia. He was en route to England with his family and a large shipment of sheepskin accoutrements that had been purchased by the British Army.

Backlash Against German Ancestry

While most in the Philadelphia region supported U.S. neutrality, the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary) generated enough antagonism to prompt discriminatory actions against residents of German ancestry. Federal agents raided the offices of the Tageblatt, a German newspaper in Philadelphia, and arrested staff members for treason. Philadelphians pressured the school board to halt the teaching of the German language, and vandals defaced statues of Goethe, Schiller, and Bismarck. As in other American communities, sauerkraut was renamed “Liberty Cabbage,” and Christmas legends such as Kris Kringle and Santa Claus were banned from public mention.

German Americans throughout the region, especially in Philadelphia, protested the rhetoric directed against them as well as U.S. involvement in the war. German Americans asked Philadelphia officials to help develop a better understanding of Germany and its people and to denounce anti-German demonstrations. Many of Philadelphia’s German Americans also called upon the United States to cease shipping goods to the Allies. Their actions only served to deepen suspicions. Socialists and Quakers also opposed U.S. entry into the war.

War created a significant boost to the region’s industries, which produced clothing, ammunition, weapons, and war machines for the U.S. military and the Allies. Even before U.S. entry into the conflict on April 6, 1917, the war helped to reinvigorate the region’s textile industry, which had been suffering in the early twentieth century. For example, the Dobson’s Mills, located in Kensington, Manayunk, and Germantown, filled an order for 100,000 blankets to the French army in the first year of the war, while the Roxford Knitting Mill in Kensington filled a similar-sized order for underwear. Area shipyards expanded, producing 328 ships during the war years. The New York Shipbuilding Corporation in South Camden and the Pusey and Jones Shipbuilding Corporation in Gloucester City became major contributors to the war effort. The war also vastly expanded the Camden Forge, a major supplier for the shipyards. The Baldwin Locomotive Works manufactured artillery shells and other munitions. Seventy-five percent of the military’s boots and shoes came from Philadelphia tanners.

Du Pont Prospers

In Delaware, the gunpowder manufacturer E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company vastly expanded its munitions production, from $25 million in sales 1914 to $319 million in 1918. Providing 40 percent of the munitions used by the Allied Forces during World War I, DuPont became one of the wealthiest companies in history. Its profits during World War I later drew scrutiny from the U.S. Senate, which held a series of committee hearings in the 1930s to investigate the role of industry in the U.S. decision to enter the war. Pierre S. du Pont (1870-1954) was among the industrialists called to testify.

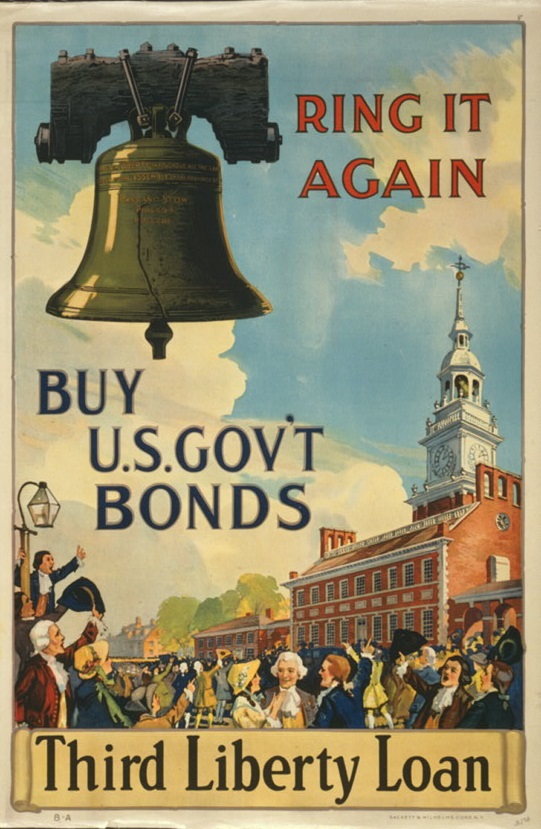

Homefront civilians contributed to the war in a number of ways. They donated extensively to the three major “Liberty Loan” campaigns, which allowed Americans to contribute capital to the war effort. Further developing a connection between the “Liberty Loan” and Philadelphia was the use of the Liberty Bell as the campaign’s official symbol. The campaign was so popular in Philadelphia that it was oversubscribed.

During the war, the City of Philadelphia urged residents to use less food and fuel, even going as far as to implement “heatless Mondays,” when people were expected to use no fuel, and “wheatless Wednesdays,” when they were to avoid using wheat or wheat products. Contributions to the war effort caused dramatic shortages in food, fuel, and other necessities. During the late years of the war, some Philadelphia businesses and other commercial buildings closed due to a lack of coal and food.

Rise of Americanization Programs

Progressive reformers also joined the war effort. Growing fears about the loyalty of immigrants spurred Americanization programs to promote assimilation of immigrants to American customs, language, and social norms. Advocates of Prohibition also used the war to their advantage by arguing that beer consumers were anti-American and pro-German. They suggested the grain used to make beer could be better used to feed those in need in Europe.

While the war created difficult conditions for many, it also opened doors to new opportunities. Many women filled the jobs of men who were drafted or serving in the military. They organized Liberty Bond drives and other fundraisers. Women joined the Red Cross in great numbers and served as nurses overseas, and some women enlisted in the military. While they did not serve in combat, they worked in offices and other clerical positions. The U.S. military enlisted nearly 2,000 women from the city of Philadelphia.

Wartime growth of industry and labor shortages in the North also drew southern African Americans to northern industrial cities in a movement that became known as the Great Migration. African Americans who wanted to escape economic hardship, threats of violence, and discriminatory Jim Crow laws in the South hoped to find better opportunities in the North. In Philadelphia, Camden, Chester, and other cities, African Americans sought employment in industries including Baldwin Locomotive, the Pennsylvania Railroad, the Reading Railroad, and Midvale Steel. While African Americans were poorly paid and forced to perform the least-desirable jobs, their chances for economic independence and advancement were better in the Philadelphia region than in the South.

Competition for Jobs and Housing

White Philadelphians, especially recent immigrants, saw African Americans as competitors for jobs and housing and resisted their arrival. In July 1918, after an African American woman moved into a house at 2936 Ellsworth Street in Philadelphia, a white neighborhood, angry white residents stoned the house and attacked nearby African Americans. The event triggered a riot that lasted two days and resulted in deaths of one African American and two whites. The threat of violence became so intense that the Colored Protective Association formed to assert the rights of African Americans.

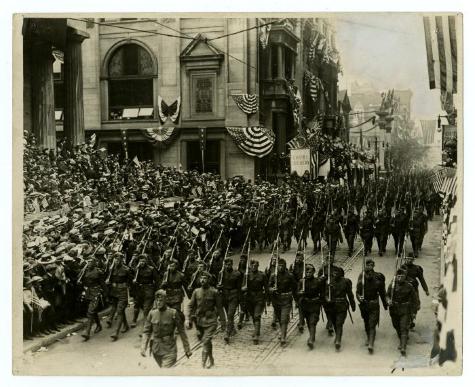

While many of the area’s residents contributed to the war effort at home, thousands crossed the Atlantic to fight for the Allies in Europe. Nearly 60,000 men were called to arms from Philadelphia and surrounding neighborhoods. Large groups of these men served in single divisions, which resulted in numerous Philadelphians being killed at the same time. For example, 7,000 Philadelphian men served in the Army’s Twenty-Eighth Infantry Division, which saw constant combat at the front in Marne and Argonne, France, throughout 1918. The Seventy-Ninth Infantry Division also drafted a large portion of its men from Philadelphia.

The success of the Allies in Europe came at a price. As the war came to a close, the area experienced two major challenges. First, the industrial boom came to an abrupt end. No longer supported by the high demand for war matériel, many of the factories and mills in Philadelphia, Camden, and the surrounding area closed in the early 1920s. Dobson’s textile mills, for example, were hit particularly hard. The company, which had delivered 30,000 blankets to the United States Army each week and grossed $20 million in the last year of the war, began closing mills in the early 1920s. By 1928 the last of the Dobson’s mills had closed. In Camden, the New York Shipbuilding Company as well as other industrial firms had to lay off many of their employees. Massive layoffs exacerbated growing social unrest spurred on by the red scare.

The second challenge came in the form of an influenza epidemic. The epidemic struck Philadelphia, Camden, and other cities particularly hard because of their dense populations. Measures were taken to limit the spread of the infectious disease, such as closing theaters, schools, saloons, and other public places. In just four weeks between October and November of 1919, the influenza epidemic claimed the lives of many more Philadelphians than had been killed during the entire course of the war.

World War I provided the “Workshop of the World” and the surrounding area the opportunity to flex its industrial prowess. Philadelphia produced massive quantities of goods for the war effort, and the war gave women and African Americans the opportunity to become more active in public and in the workforce. However, the war also brought with it discrimination against German American citizens, food and fuel shortages, and the death of nearly 1,400 Philadelphia men. When the war came to an end, workers, beginning with African Americans and women, were laid off in great numbers, and industries and businesses began to close, creating new challenges for the years ahead.

Jacob Downs has a master’s degree in history from Rutgers University-Camden. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Together We Win: The Philadelphia Homefront During the First World War (Digital Exhibit, Library Company of Philadelphia)

- Home Before the Leaves Fall: The Great War

- Remembering World War I (Villanova University)

- Philadelphia in the World War, 1914-1919 (Internet Archive)

- Pennsylvania in the World War And Illustrated History of the Twenty-Eighth Division (Google Books)

- Food Will Win the War (PhillyHistory.org)

- New York Shipbuilding Corporation: Photographic Impressions of the World's Largest Shipyard (Google Books)

- The U.S. Food Administration, Women, and the Great War: The Pennsylvania Food Conservation Train (Cultural Institute Powered by Google)

- World War I Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)