War artist Jack Shadbolt depicts a member of the Veterans Guard of Canada on duty at the German prisoner-of-war camp in Petawawa, Ont., in late 1944.[Jack Shadbolt/CWM/19710261-5869]

On May 10, 1940, the Germans launched a massive onslaught against western Europe. Shockingly, after two weeks, France was on the verge of collapse and the British Isles themselves seemed imperilled. Every man was needed, and Canada accelerated its military preparations. Under these dire circumstances was born one of the least-known Canadian Army organizations of the Second World War: the Veterans Guard of Canada.

On May 23, Defence Minister Norman Rogers announced the urgent creation of the Veterans Home Guards, a force necessary “for the more adequate protection of military property or for any other purpose that may be found necessary in Canada.” Volunteers were to be exclusively First World War veterans having served in Canadian or British forces. The men needed to be less than 50 years old (later 55), fit and honourably discharged.

The war was drawing nearer to Canada and the veteran soldiers would be required to protect key infrastructure and industrial sites, including power stations, bridges, canals, dockyards, government buildings and munitions factories against the presumed threat from saboteurs. The force’s principal task was guarding civilian internment camps and, later, prisoner-of-war camps. It was never intended that these veterans would see combat.

The Department of National Defence originally authorized 12 companies of 250 men, each commanded by a major, consisting of a company headquarters and six platoons of 39 men, all ranks. In September 1940, the force was expanded, and its name was changed to the Veterans Guard of Canada. The guard was not an auxiliary force nor a group of well-meaning civilian veterans; it was an integral part of the Canadian Army. The men wore battle dress, were issued Ross Rifles or SMLEs, had the same service obligations and received the same pay ($1.30 a day) and allowances as other soldiers.

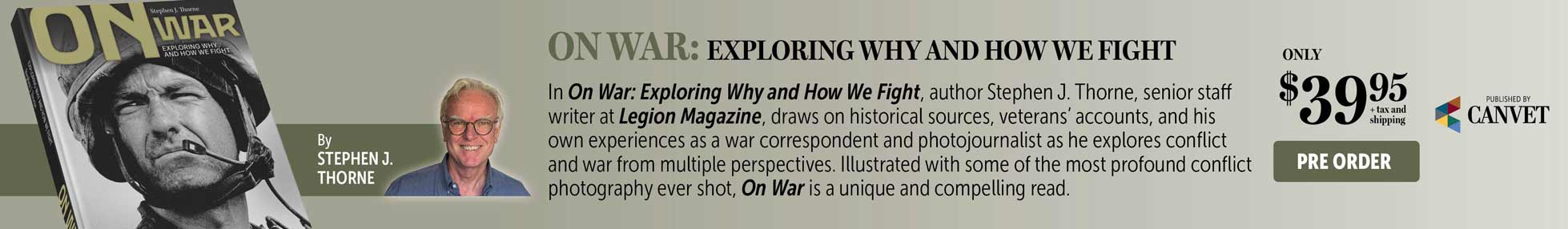

The unit was featured on the cover of the September 1943 issue of The Legionary, this magazine’s previous name.

The sudden creation of the guard was partly in response to the vocal demands of veterans’ organizations, especially the Canadian Legion, eager to employ the veterans’ military experience in aid of the war effort. But, as The Legionary magazine noted, “The old soldier is now just a bit too old for the rigours of modern hostilities, however much it may pain him to admit the fact.” Many veterans had been rejected at recruiting offices and the guard offered healthy vets anxious to do their bit a chance to serve anew.

Thousands of veterans across Canada flooded the special recruiting centres established for the guard in each military district. These were the men of Ypres, the Somme, Vimy and Passchendaele, and included hundreds who had served with British forces. Many wore their campaign medals and gallantry awards, and they came from all backgrounds and walks of life.

In Montreal, more than 1,000 veterans queued to enlist. One impressed reporter wrote of the “grizzled ex-servicemen…back in uniform to do their bit once more in the country’s present hour of need.”

Sometimes it was the veterans who were in need. Henry Patry, who had proceeded overseas with the 1st Canadian Division in 1914, had six children, survived on relief and reportedly stated that “he would rather be working with the vets than starving at home.”

While some 25,000 veterans from across the country had volunteered for the guard by the end of 1940, most were rejected based on age or medical reasons.

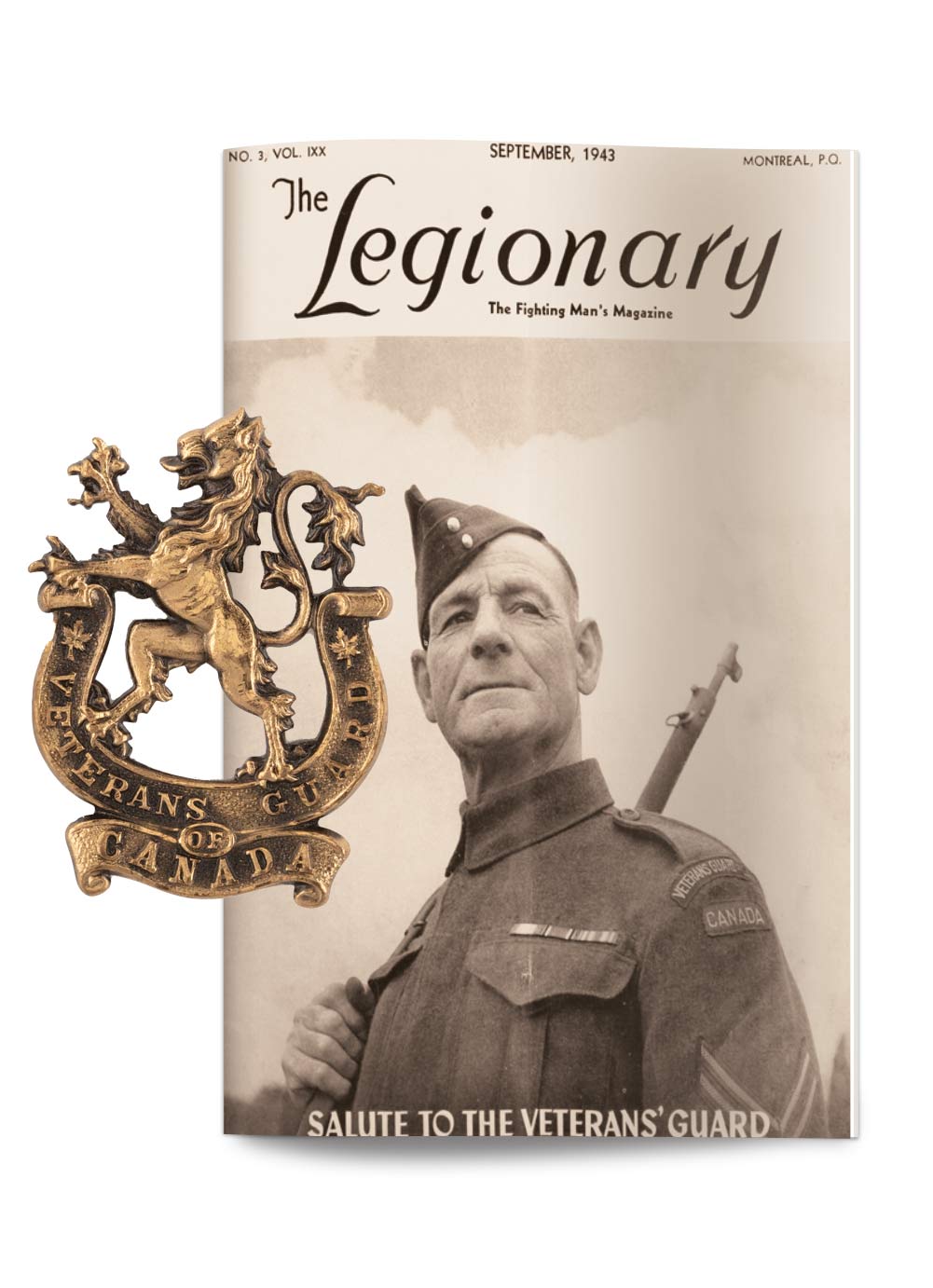

Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert R. Alley took command of the guard in September 1940. The government ran ads such as this one recruiting veterans for the unit. [Courtesy Serge Durflinger; CWM/19750317-021]

“Only the highest sense of duty and responsibility could have caused these men to forsake their loved ones for the hardships of Active Service.”

The training was intensive, and the men had to meet the basic physical standards of the active army, even if many of them stood to lose a few pounds. There was field training and course work covering map reading, military law, field engineering, administration and tactics, thereby enabling the men to advance in rank. Of course, this was “refresher” work for many.

Lieutenant-Colonel (later Colonel) Herbert R. Alley of Toronto had taken command of the guard in September 1940. Since guard detachments across Canada were under the direct command of the district officers commanding each military district, Alley was given the bureaucratic title of officer administering (later director). He had formerly served as president of Ontario Command of the Legion.

During the First World War, Alley had been wounded at Courcelette in 1916 while serving in the 3rd Battalion. Because the guard’s cap badge was a lion rampant, the men sometimes referred to themselves as the “Alley Cats.”

The officer administering reported to the army adjutant-general and was responsible for the guard’s supply and reinforcement needs and personnel matters such as appointments and promotions. In August 1944, Colonel James M. Taylor of Medicine Hat, Alta., replaced Alley. Taylor had received the Military Cross for his action at Amiens, France, in 1918. In civilian life he had been a Calgary police officer.

The guard was headquartered on Rideau Street in Ottawa, and by March 1941, it boasted, in the words of The Legionary, almost 6,500 “greying but virile” veterans on active service in 29 companies, with another 4,000 part-time volunteers in reserve companies attached to army reserve units across Canada. In June 1943, the guard’s strength peaked at 451 officers and 9,806 other ranks. During the war, more than 15,000 veterans served with 37 regular and three special-duty companies.

In September 1943, the Legion estimated that more than 500 veterans serving in regular or reserve companies were holders of gallantry awards and honours, including two Victoria Cross recipients, Lieutenant George H. Mullin and Lieutenant Charles S. Rutherford.

“Only the highest sense of duty and responsibility could have caused these men to forsake their homes, their loved ones, their hard-won ease, for the hardships and heartaches of Active Service,” wrote The Legionary. “That they have done so is a high tribute to their patriotism and loyalty.”

After Japan’s entry into the war in December 1941, the guard helped operate coastal defences and guarded Royal Canadian Air Force bases in B.C. They also protected the aluminum smelting facilities at Arvida, Que., that were so critical to the Allied war effort.

By far the guard’s most important role, however, was supervising the 26 internment and PoW camps across Canada that eventually housed some 34,000 Germans. At first, the Canadian Provost Corps did the work but, in May 1941, the responsibility passed to the guard. The veteran soldiers manned guard towers, carried out inspections and oversaw all the prisoners’ activities.

Many of these camps were in remote locations, such as Angler, Ont., on Lake Superior, or Ozada, Alta. The weather was harsh and the living conditions basic where the middle-aged men engaged in monotonous and even “soul-stagnating” duties, as The Legionary remarked.

On the guard’s third anniversary, The Globe and Mail reminded readers that, “There is, perhaps, no less-appreciated force in the Canadian armed services than this unit of 11,000 veterans of the last war.”

Admitting that the guard’s formation had been “on a rather loose and hurried basis,” the force had become efficient, “performing quite special functions out of sight of the public.”

These important jobs needed the “experience, stability, [and] self-discipline not found in recruits.”

Guarding Canada’s PoW camps was “a thankless chore, the importance of which, not to mention the drudgery, is constantly minimized. The fact is that we realize there is a Guard only when it is under the adverse publicity of a prison break. Accordingly, the Guards are criticized but seldom blessed.”

The aging soldiers fought one major engagement during the war: the Battle of Bowmanville in October 1942. The three-day riot at the PoW camp in the small town about 75 kilometres east of Toronto on Lake Ontario featured pitched fighting between the vets and much younger Germans with fists, broom handles and hockey sticks.

It resulted in numerous casualties on both sides. One guard officer was captured and beaten. Warning shots were fired, and one prisoner received a ricochet wound in the leg, while two others received bayonet wounds. The fracas ended when 200 reinforcements of officer-cadets arrived from Kingston and stormed the barracks in which the Germans had barricaded themselves.

Despite this violent incident, some former German prisoners recalled the guard with fondness. Horst Braun remembered that the Canadian veterans took pleasure in teaching him English, while Leo Hoecker stated after the war that “those veteran guards really treated us well.”

Although most of the guard served only in Canada, small detachments were sent abroad. They protected Canadian Military Headquarters in London, garrisoned the Bahamas, protected bauxite-laden ships in British Guiana, defended RCAF installations in Newfoundland and, in 1944-45, even escorted several shipments of mules to India.

In May 1945, an editorial in The Montreal Daily Star said that the men’s service had “directly or indirectly released the equivalent of a full infantry division for combat and other active duty, [and] they have carried out essential war functions requiring a uniformed body of trained, disciplined, and armed men.”

Importantly, more than 1,500 veteran soldiers had transferred into other units of the army, often serving as instructors or specialists.

The Veterans Guard of Canada quickly wound down at war’s end, though some men escorted German PoWs back to Britain. It was disbanded in March 1947. It had lost 336 men from illness or accidents.

An unnamed British-born member of the guard who had mainly served at various PoW camps said 20 years after the war that “all of us who served were pleased to have done something to help, and I for one would not have missed the experience for anything.”

Guard member Alan Horwood, meanwhile, penned “Veterans,” a wartime ode to his comrades’ service that encapsulated the men’s devotion during the war. It read in part:

“…sagging shoulders stiffen

in salute

As youth swings by;

His martial spirit flames on undiminished

They did not shrink from duty when once more …

They vied with youth,

eager to do their share.”

Another of Shadbolt’s works depicts the guard in service at the PoW camp in Petawawa, Ont., late in the war. [CWM/19710261-5847]

Advertisement