Pravda

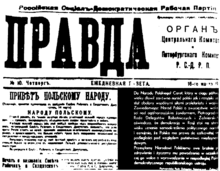

First issue, 5 May 1912 (22 April 1912 OS) | |

| Type | Triweekly newspaper |

|---|---|

| Format | Broadsheet |

| Owner(s) | Communist Party of the Russian Federation |

| Editor | Boris Komotsky |

| Founded | 5 May 1912 (officially) |

| Political alignment | Communism Marxism–Leninism |

| Language | Russian |

| Headquarters | 24, Pravda Street, Moscow |

| Country | |

| Circulation | 100,300 (2010) |

| ISSN | 0233-4275 |

| Website | Pravda's website (CPRF branch) |

Pravda (Russian: Правда, IPA: [ˈpravdə] , lit. 'Truth') is a Russian broadsheet newspaper, and was the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, when it was one of the most influential papers in the country with a circulation of 11 million.[1] The newspaper began publication on 5 May 1912 in the Russian Empire but was already extant abroad in January 1911.[2] It emerged as the leading government newspaper of the Soviet Union after the October Revolution. The newspaper was an organ of the Central Committee of the CPSU between 1912 and 1991.[3] After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Pravda was sold by the then Russian president Boris Yeltsin to a Greek business family in 1992, and the paper came under the control of their private company Pravda International.[1][4]

In 1996, there was an internal dispute between the owners of Pravda International and some of the Pravda journalists that led to Pravda splitting into different entities. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation (CPRF) acquired the Pravda paper, while some of the original Soviet Pravda journalists separated to form Russia's first online paper Pravda Online (now Pravda.ru), which is not connected to the Communist Party.[4][5] The Pravda paper is still run by the CPRF, whereas the online Pravda.ru is privately owned and has international editions published in Russian, English, French, and Portuguese. After a legal dispute between the rival parties, the Russian court of arbitration stipulated that both entities would be allowed to continue using the Pravda name.[6]

Origins

[edit]Pre-revolutionary Pravda

[edit]Though Pravda officially began publication on 5 May 1912 (22 April 1912 OS), the anniversary of Karl Marx's birth, its origins trace back to 1903 when it was founded in Moscow by a wealthy railway engineer, V.A. Kozhevnikov. Pravda had started publishing in the light of the Russian Revolution of 1905.[7] At the time when the paper was founded, the name "Pravda" already had a clear historical connotation, since the law code of the Medieval Kievan Rus' was known as Russkaya Pravda;[8][9] in this context, "Pravda" meant "Justice" rather than "Truth", "Russkaya Pravda" being "Russian Justice".[citation needed] This early law code had been rediscovered and published by 18th-century Russian scholars, and, in 1903, educated Russians with some knowledge of their country's history could have been expected to know the name.

During its earliest days, Pravda had no political orientation. Kozhevnikov started it as a journal of arts, literature and social life. Kozhevnikov was soon able to form up a team of young writers including A.A. Bogdanov, N.A Rozhkov, M.N Pokrovsky, I.I Skvortsov-Stepanov, P.P Rumyantsev and M.G. Lunts, who were active contributors on 'social life' section of Pravda. Later, they became the editorial board of the journal, and, in the near future, also became the active members of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP).[7] Because of certain quarrels between Kozhevnikov and the editorial board, he had asked them to leave and the Menshevik faction of the RSDLP took over as the editorial board. But the relationship between them and Kozhevnikov was also a bitter one.[7]

The Ukrainian political party Spilka, which was also a splinter group of the RSDLP, took over the journal as its organ. Leon Trotsky was invited to edit the paper in 1908, and the paper was moved to Vienna in 1909. By then, the editorial board of Pravda consisted of hard-line Bolsheviks who sidelined the Spilka leadership soon after it shifted to Vienna.[10] Trotsky had introduced a tabloid format to the newspaper and distanced itself from the intra-party struggles inside the RSDLP. During those days, Pravda gained a large audience among Russian workers. By 1910, the Central Committee of the RSDLP suggested making Pravda its official organ.

At the sixth conference of the RSDLP held in Prague in January 1912, the Menshevik faction was expelled from the party. The party under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin decided to make Pravda its official party organ. The paper was shifted from Vienna to St. Petersburg and the first issue under Lenin's leadership was published on 5 May 1912 (22 April 1912 OS).[11] It was the first time that Pravda was published as a legal political newspaper. The Central Committee of the RSDLP, workers and individuals such as Maxim Gorky provided financial help to the newspaper. The first issue published on 5 May cost two kopecks and had four pages. It had articles on economic issues, workers movement, and strikes, and also had two proletarian poems. M.E. Egorov was the first editor of St. Petersburg Pravda and Member of State Duma of the Russian Empire Nikolay Poletaev served as its publisher.[12]

Egorov was not a real editor of Pravda but this position was pseudo in nature. As many as 42 editors had followed Egorov within a span of two years, till 1914. The main task of these editors was to go to jail whenever needed and to save the party from a huge fine.[12] On the publishing side, the party had chosen only those individuals as publishers who were sitting members of Duma because they had parliamentary immunity. Initially,[when?] it had sold between 40,000 and 60,000 copies.[12] With the outbreak of World War I, the paper was closed down by tsarist authorities in July 1914. Over the next three years, it changed its name eight times because of police harassment:[13]

- Рабочая правда (Rabochaya Pravda, Worker's Truth)

- Северная правда (Severnaya Pravda Northern Truth)

- За правду (Za Pravdu, For Truth)

- Пролетарская правда (Proletarskaya Pravda, Proletarian Truth)

- Путь правды (Put' Pravdy, The Way of Truth)

- Рабочий (Rabochiy, The Worker)

- Трудовая правда (Trudovaya Pravda, Labor's Truth)

During the 1917 Revolution

[edit]

The abdication of Emperor Nicholas II during the February Revolution of 1917 allowed Pravda to reopen. The original editors of the newly revived Pravda, Vyacheslav Molotov and Alexander Shlyapnikov, were opposed to the liberal Russian Provisional Government. However, when Lev Kamenev, Joseph Stalin and former Duma deputy Matvei Muranov returned from Siberian exile on 12 March, they took over the editorial board – starting from 15 March.[14] Under Kamenev's and Stalin's influence, Pravda took a conciliatory tone towards the Provisional Government – "insofar as it struggles against reaction or counter-revolution" – and called for a unification conference with the internationalist wing of the Mensheviks. On 14 March, Kamenev wrote in his first editorial:

What purpose would it serve to speed things up, when things were already taking place at such a rapid pace?[15]

On 15 March, he supported the war effort:

When army faces army, it would be the most insane policy to suggest to one of those armies to lay down its arms and go home. This would not be a policy of peace, but a policy of slavery, which would be rejected with disgust by a free people.[16]

Soviet period

[edit]

The offices of the newspaper were transferred to Moscow on 3 March 1918 when the Soviet capital was moved there. Pravda became an official publication, or "organ", of the ruling Soviet Communist Party. Pravda became the conduit for announcing official policy and policy changes and would remain so until 1991. Subscription to Pravda was mandatory for state run companies, the armed services and other organizations until 1989.[17]

Other newspapers existed as organs of other state bodies. For example, Izvestia, which covered foreign relations, was the organ of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union, Trud was the organ of the state-controlled trade union movement, Bednota was distributed to the Red Army and rural peasants. Various derivatives of the name Pravda were used both for a number of national newspapers (Komsomolskaya Pravda was the organ of the Komsomol organization, and Pionerskaya Pravda was the organ of the Young Pioneers), and for the regional Communist Party newspapers in many republics and provinces of the USSR, e.g. Kazakhstanskaya Pravda in Kazakhstan, Polyarnaya Pravda in Murmansk Oblast, Pravda Severa in Arkhangelsk Oblast, or Moskovskaya Pravda in the city of Moscow.

Shortly after the October 1917 Revolution, Nikolai Bukharin became the editor of Pravda.[18] Bukharin's apprenticeship for this position had occurred during the last months of his emigration/exile prior to his return to Russia in April 1917.[19] These months from November 1916 until April 1917 were spent by Bukharin in New York City in the United States. In New York, Bukharin divided his time between the local libraries and his work for Novyj Mir (The New World) a Russian language newspaper serving the Russian speaking community of New York.[20] Bukharin's involvement with Novyj Mir became deeper as time went by. Indeed, from January 1917 until April when he returned to Russia, Bukharin served as de facto editor of Novyj Mir.[20] In the period after the death of Lenin in 1924, Pravda was to form a power base for Bukharin, which helped him reinforce his reputation as a Marxist theoretician. Bukharin would continue to serve as editor of Pravda until he and Mikhail Tomsky were removed from their responsibilities at Pravda in February 1929 as part of their downfall as a result of their dispute with Joseph Stalin.[21]

A number of places and things in the Soviet Union were named after Pravda. Among them was the city of Pravdinsk in Gorky Oblast (the home of a paper mill producing much newsprint for Pravda and other national newspapers), and a number of streets and collective farms.

As the names of the main communist newspaper and the main Soviet newspaper, Pravda and Izvestia, meant "the truth" and "the news" respectively, a popular saying was "there's no news in Pravda and no truth in Izvestia".[22] Though not highly appreciated as an objective and unbiased news source, Pravda was regarded – both by Soviet citizens and by the outside world – as a government mouthpiece and therefore a reliable reflection of the Soviet government's positions on various issues. The publication of an article in Pravda could be taken as indication of a change in Soviet policy or the result of a power struggle in the Soviet leadership, and Western Sovietologists were regularly reading Pravda and paying attention to the most minute details and nuances.

Post-Soviet period

[edit]After the dissolution of the Soviet Union Pravda was sold by Russian President Boris Yeltsin to a Greek business family – the Giannikoses – in 1992, and the paper came under the control of their private company Pravda International.[1][4][23]

In 1996, there was an internal dispute between the owners of Pravda International and some of the Pravda journalists which led to Pravda splitting into different entities. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation acquired the Pravda paper, while some of the original Pravda journalists separated to form Russia's first online paper (and the first online English paper) Pravda.ru, which is not connected to the Communist Party, but is run by journalists associated with the defunct Soviet Pravda.[4][5] After a legal dispute between the rival parties, the Russian court of arbitration stipulated that both entities would be allowed to continue using the Pravda name.[6] The Pravda paper is today run by the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, whereas the online Pravda.ru is privately owned and has international editions published in Russian, English, French and Portuguese.

Pravda was a daily newspaper during the Soviet era but nowadays it is published three times a week, and its readership is largely online where it has a presence.[24][25] Pravda still operates from the same headquarters at Pravda Street in Moscow from where journalists used to work on Pravda during the Soviet era. It operates under the leadership of journalist Boris Komotsky, who is also a member of the Russian State Duma.[26]

On 5 May 2012, Pravda marked its centenary, with a grand celebration at the Trade Unions house organised by the Communist Party.[27] The gala was attended by the former and current employees of the newspaper, its readers and party members, representatives of other communist media organisations. Gennady Zyuganov made a speech, and congratulatory messages were received from Russian president Dmitry Medvedev and Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko.[28]

McCain controversy

[edit]In 2013, after Russian President Vladimir Putin published an op-ed in The New York Times in support of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad,[29] US senator John McCain announced that he would publish a response article in Pravda, referring to the newspaper owned by the Communist Party of the Russian Federation. McCain, however, eventually published his op-ed in Pravda.ru.[30] This caused protests from the editor of communist Pravda Boris Komotsky and a response from the editor of Pravda.ru Dmitry Sudakov: Komotsky claimed that "there is only one Pravda in Russia, it is the organ of the Communist Party, and we have heard nothing about the intentions of the Republican senator" and dismissed Pravda.ru as an "Oklahoma-City-Pravda", while Sudakov derided Komotsky, claiming that "the circulation of the Communist Party Pravda is like a factory newspaper of AvtoVAZ from the Soviet times".[31][32][33] McCain later attempted to publish his op-ed in the Communist Pravda as well, but the paper refused to publish it "because it was not aligned to the political positions of the Communist Party of the Russian Federation".[34]

Editors-in-chief

[edit]The editorship of Pravda during its early years was collective and constantly changing; only the more important figures are listed here.[35]

- Joseph Stalin, Yakov Sverdlov, Miron Chernomazov, Lev Kamenev, Vyacheslav Molotov (1912–1914)

- Vyacheslav Molotov, Alexander Shliapnikov, Konstantin Eremeev, Mikhail Kalinin (5–13 March 1917)

- Joseph Stalin, Matvei Muranov, Lev Kamenev (13 March – 4 April 1917)

- Vladimir Lenin, Grigory Zinoviev, Joseph Stalin, Matvei Muranov, Lev Kamenev (4 April – 5 July 1917)

- Yakov Sverdlov and others (6 July – 9 December 1917)

- Nikolai Bukharin (10 December 1917 – 23 February 1918)

- Unknown (24 February – July 1918)

- Nikolai Bukharin (July 1918 – October 1928; nominally until April 1929)

- Harald Krumin (1929–1930)

- Maximilian Saveliev (1930)

- Lev Mekhlis (1930–1937)

- Alexander Poskrebyshev (1937–1940)

- Pyotr Pospelov (1940–1949)

- Mikhail Suslov (1940–1951)

- Leonid Ilyichev (1951–1953)

- Dmitri Shepilov (1953–1956)

- Pavel Satyukov (1956–1964)

- Aleksei Rumyantsev (1964–1965)

- Mikhail Zimyanin (1965–1976)

- Viktor Afanasyev (1976–1989)[35]

- Ivan Frolov (1989–1991)

- Gennadiy Seleznyov (1991–1993)

- Viktor Linnik (1993–1994)

- Aleksander Ilyin (1994–2003)

- Valentina Nikiforova (2003–2005; acting)

- Valentin Shurchanov (2005–2009)

- Boris Komotsky (2009–present)

Similar newspapers in current communist countries

[edit]- People's Daily – People's Republic of China, official newspaper of the Chinese Communist Party;

- Rodong Sinmun – North Korea, official newspaper of the Workers' Party of Korea;

- Granma – Cuba, official newspaper of the Communist Party of Cuba;

- Nhân Dân – Vietnam, official newspaper of the Communist Party of Vietnam;

- Pasaxon – Laos, official newspaper of the Lao People's Revolutionary Party;

See also

[edit]- Kommunist

- Komsomolskaya Pravda

- Kommunistka

- Iskra

- Izvestia

- Krasnaya Zvezda

- Central newspapers of the Soviet Union

- Eastern Bloc information dissemination

- Freedom of the press in Russia

- Vitali Korionov

- Mass media in Russia

- People's correspondent

- Zreniye

- Völkischer Beobachter

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ a b c Specter, Michael (31 July 1996). "Russia's Purveyor of 'Truth', Pravda, Dies After 84 Years". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ V. I. Lenin, Collected Works, Progress Publishers Moscow, Volume 17, p.45

- ^ Merrill, John C. and Harold A. Fisher. The world's great dailies: profiles of fifty newspapers (1980) pp 242–49

- ^ a b c d "Pravda | Soviet newspaper". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ a b "Which Pravda did John McCain write about Syria for?". the Guardian. 19 September 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ a b "There is no Pravda. There is Pravda.Ru". English pravda.ru. 16 September 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ a b c White, James D. (April 1974). "The first Pravda and the Russian Marxist Tradition". Soviet Studies, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 181–204. Accessed 6 October 2012.

- ^ "Yaroslav I". The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (15th ed.). 2003. p. 823. ISBN 9780852299616.

Under Yaroslav the codification of legal customs and princely enactments was begun, and this work served as the basis for a law code called the Russkaya Pravda ("Russian Justice").

- ^ Yaroslav Padokh (1993). "Ruskaia Pravda". Encyclopedia of Ukraine. Vol. 4. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- ^ Corney, Frederick. (September 1985). "Trotskii and the Vienna Pravda, 1908–1912". Canadian Slavonic Papers. Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 248–268. Accessed 6 October 2012.

- ^ Bassow, Whitman. (February 1954) "The Pre Revolutionary Pravda and Tsarist Censorship". American Slavic and East European Review. Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 47–65. Accessed 6 October 2012.

- ^ a b c Elwood, Carter Ralph. (June 1972) "Lenin and Pravda, 1912–1914". Slavic Review. Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 355–380. Accessed 6 October 2012.

- ^ See Tony Cliff's Lenin. Vol 1: Building the Party (1893-1914) (1975). London: Pluto Press. Chapter 19. OCLC 1110326753.

- ^ Leon Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, translated by Max Eastman, Chicago, Haymarket Books, 2008, p. 209

- ^ See Marcel Liebman, Leninism under Lenin, London, J. Cape, 1975, ISBN 978-0-224-01072-6 p.123

- ^ See E. H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, London, Macmillan Publishers, 1950, vol. 1, p. 75.

- ^ See Mark Hooker. The Military Uses of Literature: Fiction and the Armed Forces in the Soviet Union, Westport, CT, Praeger Publishers, 1996, ISBN 978-0-275-95563-2 p.34

- ^ Stephen F. Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888–1938 (Oxford University Press: London, 1980) p. 43.

- ^ Stephen F. Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888–1938, p. 44.

- ^ a b Stephen F. Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888–1938, p. 43.

- ^ Stephen F. Cohen, Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography, 1888–1938, p. 311.

- ^ Overholser, Geneva. (12 May 1987). "The Editorial Notebook; Dear Pravda" New York Times. Accessed 6 October 2012.

- ^ "Black, white and red no longer: Pravda folds". Tampa Bay Times. 16 September 2005 [31 July 1996]. Retrieved 25 August 2022.

- ^ "Russian newspaper Pravda (Truth) celebrates its 100th anniversary". NBC News. 4 May 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "The Communist Party of the Russian Federation today".

- ^ "Комоцкий, Борис Олегович" (in Russian). ТАСС. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- ^ ""Правда" на все времена. В Колонном зале Дома Союзов прошёл праздничный вечер, посвящённый 100-летию главной партийной газеты | KPRF.RU". Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ "Коллективу редакции газеты "Правда" | Президент России". 5 May 2012. Archived from the original on 31 October 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- ^ Putin, Vladimir V. (12 September 2013). "Opinion | A Plea for Caution From Russia". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ McCain, John (19 September 2013). "Senator John McCain: Russians deserve better than Putin". Pravda.ru.

- ^ Guardian Staff (19 September 2013). "Which Pravda did John McCain write about Syria for?". the Guardian. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Sudakov, Dmitry (16 September 2013). "There is no Pravda. There is Pravda.Ru". Pravda.ru. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ "McCain claim leaves Communist Party baffled | eNCA". eNCA. Archived from the original on 21 January 2022. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- ^ Kopan, Tal (19 September 2013). "Truthfully, McCain in wrong Pravda". Politico.

- ^ a b Roxburgh, Angus (1987). Pravda: Inside the Soviet News Machine. New York: George Braziller. p. 282. ISBN 9780807611869.

Further reading

[edit]- Brooks, Jeffrey. Thank You, Comrade Stalin!: Soviet Public Culture from Revolution to Cold War (Princeton Up, 2001) on the language of Pravda and Izvestia

- Cookson, Matthew (11 October 2003). The spark that lit a revolution Archived 14 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Socialist Worker, p. 7.

- Merrill, John C. and Harold A. Fisher. The world's great dailies: profiles of fifty newspapers (1980) pp 242–49

- Pöppel, Ludmila. "The rhetoric of Pravda editorials: A diachronic study of a political genre." (Stockholm U. 2007). online

External links

[edit]- Pravda Newspaper

- Some articles published in Pravda in the 1920s

- 100 Years of Pravda Video Clip

- "Pravda" digital archives in "Newspapers on the web and beyond", the digital resource of the National Library of Russia

- Pravda Digital Archive, access from 1912 to present

- Archive of Pravda issues from 1918 to 1991