History of sign language

The recorded history of sign language in Western societies starts in the 17th century, as a visual language or method of communication, although references to forms of communication using hand gestures date back as far as 5th century BC Greece. Sign language is composed of a system of conventional gestures, mimic, hand signs and finger spelling, plus the use of hand positions to represent the letters of the alphabet. Signs can also represent complete ideas or phrases, not only individual words.

Most sign languages are natural languages, different in construction from oral languages used in proximity to them, and are employed mainly by deaf people in order to communicate. Many sign languages have developed independently throughout the world, and no first sign language can be identified. Both signed systems and manual alphabets have been found worldwide. Until the 19th century, most of what we know about historical sign languages is limited to the manual alphabets (fingerspelling systems) that were invented to facilitate transfer of words from an oral to a sign language, rather than documentation of the sign language itself.

History of known sign languages

[edit]

One of the earliest written references to a sign language is from the fifth century BC, in Plato's Cratylus, where Socrates says: "If we hadn't a voice or a tongue, and wanted to express things to one another, wouldn't we try to make signs by moving our hands, head, and the rest of our body, just as dumb people do at present?"[1]

In the Middle Ages, monastic sign languages were used by a number of religious orders in Europe since at least the 10th century. These are not true "sign languages", however, but well-developed systems of gestural communication.[2][3][4][5]

In Native American communities prior to 1492, it seems that Plains Indian Sign Language existed as an extensive lingua franca used for trade and possibly ceremonies, story-telling and also daily communication by deaf people.[6] Accounts of such signing indicate these languages were fairly complex, as ethnographers such as Cabeza de Vaca described detailed communications between them and Native Americans that were conducted in sign. In the 1500s, a Spanish expeditionary, Cabeza de Vaca, observed natives in the western part of modern-day Florida using signs,[7] and in the mid-16th century Coronado mentioned that communication with the Tonkawa using signs was possible without a translator.[citation needed]

The earliest concrete reference to sign language in Britain is from the wedding of a deaf man named Thomas Tillseye in 1575.[8] Descendants of British Sign Language have been used by deaf communities (or at least in classrooms) in former British colonies India, Australia, New Zealand, Uganda and South Africa, as well as the republics and provinces of the former Yugoslavia, Grand Cayman Island in the Caribbean, Indonesia, Norway, and Germany.[citation needed]

Between 1500 and 1700, it seems that members of the Turkish Ottoman court were using a form of signed communication.[9] Many sought-after servants were deaf, as, some argue, they were seen as more quiet and trustworthy. Many diplomats and other hearing members of the court, however, also learned and communicated amongst one another through this signing system, which was passed down through the deaf members of the court.[9]

In the 18th century, Paris was home to a small deaf community that signed among themselves in Old French Sign Language. This was referenced by l'Abbé Charles Michel de l'Épée who created the first school for the deaf in Paris in the 18th century. He defined his own manual alphabet and synthesized signs with French grammar. With consistent use among the community these two sources evolved into the French Sign Language.[10] American Sign Language is heavily based on French Sign Language due to the presence of teachers from France in the first American schools for the deaf.

Some sign languages are known to have developed spontaneously in small communities with a high number of deaf members. Martha's Vineyard, an island in Massachusetts, USA was settled by people carrying a gene causing deafness in the late 17th century. Limited outside contact and high inter-marriage on the island led to a high density of deaf individuals on the island, peaking around 1840.[11] This environment proved ideal for the development of what is today known as Martha's Vineyard Sign Language, which was used by hearing and deaf islanders alike until increased mixing with the outside world reduced the incidence of deafness on the island. They created a sign language that had specific signs relevant to that area, such as native types of fish and berries.[12] Almost all of the school-aged population became students at ASD, which led to mutual influence of American Sign Language and Martha's Vineyard Sign Language on each other.

Perception of sign language through history

[edit]In Europe, Aristotle and other prominent philosophers[13] believed that deafness was intrinsically connected to mutism and lack of intelligence, which was codified in Roman law; therefore they were considered incapable of being educated.[14] When John of Beverley, Bishop of York, taught a deaf person to speak in 685 AD, it was deemed a miracle, and he was later canonized.[11]

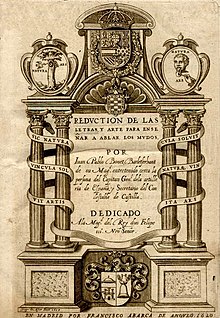

European education for the deaf is not recorded until the 16th century, when Pedro Ponce de León began tutoring deaf children of wealthy patrons – in some places, literacy was a requirement for legal recognition as an heir. The first book on deaf education, published in 1620 by Juan Pablo Bonet in Madrid, included a detailed account of the use of a manual alphabet to teach deaf students to read and speak.[15] It is considered the first modern treatise on phonetics and speech therapy, setting out a method of oral education for deaf children. In Britain, Thomas Braidwood founded the first school for the deaf in the late 1700s. He was secretive about his teaching methods but probably used sign language, finger spelling and lip reading.[citation needed]

l'Abbé Charles Michel de l'Épée started the first school for deaf children in Paris, in 1755.[citation needed] Laurent Clerc was arguably the most famous graduate of L'Épee's school; Clerc went to the United States with Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet to found the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817. In France and the United States, sign language, or "manualism" was initially the favored communication method for education of deaf students, firmly supported by Clerc and therefore Gallaudet.[16] In England and Germany oralism was considered to be superior - sign language was thought to be a mere collection of gestures, and a barrier between deaf people and hearing society.[17][18] In 1880, the International Congress on the Education of the Deaf (ICED) met in Milan with 164 educators attending (only one of them being deaf). At this meeting they passed a resolution removing the use of sign language from deaf education, and establishing the solely oralist classroom as standard.[19] In line with this philosophy, manually coded languages have been created and used for education instead of sign language, such as Signing Exact English.

The debate between oralism and manualism remained active after Milan. In the late 20th century educators and researchers began to understand the importance of sign language to language acquisition. In 1960 when the linguist William Stokoe published Sign Language Structure, it advanced the idea that American Sign Language was a complete language. Over the next few decades sign language became accepted as a valid first language and schools shifted to a philosophy of "Total Communication",[20] instead of banning sign language.

Wyatte C. Hall says that sign language is important for the development of deaf children growing up because without it, they could be at risk of many health difficulties. Studies have shown that the development of neuro-linguistic structures of the brain can be affected if there is a language delay. A study showed that there is an "age of acquisition" that affects adults' ability to understand grammar based on when they were introduced to sign language.[21] Data now shows that children who are heavily exposed to sign language as early as possible are better at reading English than children who are not exposed to sign language.[22]

See also

[edit]- Sign language

- Category:Sign languages

- Category:Sign languages by country

- Category:Sign language families

- American Sign Language

- Manually coded language

- Fingerspelling

- Oralism

- Deaf education

- History of deaf education in the United States

References

[edit]- ^ Bauman, Dirksen (2008). Open your eyes: Deaf studies talking. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-4619-7.[page needed]

- ^ Stokoe, William C. (1988). "Approaching Monastic Sign Language". Sign Language Studies. 1058 (58): 37–47. doi:10.1353/sls.1988.0005. JSTOR 26203846. S2CID 144705137.

- ^ Bragg, L. (1997). "Visual-Kinetic Communication in Europe Before 1600: A Survey of Sign Lexicons and Finger Alphabets Prior to the Rise of Deaf Education". Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.deafed.a014306. PMID 15579832.

- ^ Bruce, Scott G. (2007). Silence and Sign Language in Medieval Monasticism. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511496417. ISBN 978-0-521-86080-2.[page needed]

- ^ Tirosh, Yoav (January 2020). "Deafness and Nonspeaking in Late Medieval Iceland (1200–1550)". Viator. 51 (1): 311–344. doi:10.1484/J.VIATOR.5.127050. S2CID 245187538.

- ^ Nielsen, Kim (2012). A Disability History of the United States. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0-8070-2204-7.[page needed]

- ^ Bonvillian, John D.; Ingram, Vicky L.; McCleary, Brendan M. (2009). "Observations on the Use of Manual Signs and Gestures in the Communicative Interactions between Native Americans and Spanish Explorers of North America: The Accounts of Bernal Díaz del Castillo and Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca". Sign Language Studies. 9 (2): 132–165. doi:10.1353/sls.0.0013. JSTOR 26190668. S2CID 144794381. Project MUSE 259439 ProQuest 222696273.

- ^ "Session 9".

- ^ a b Miles, M. (January 2000). "Signing in the Seraglio: Mutes, dwarfs and jesters at the Ottoman Court 1500-1700". Disability & Society. 15 (1): 115–134. doi:10.1080/09687590025801. S2CID 145331019.

- ^ Judéaux, Alice (3 November 2015). "French Sign Language: a language in its own right". Tradonline.

- ^ a b Groce, Nora Ellen (1985). Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language: Hereditary Deafness on Martha's Vineyard. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-27040-4.[page needed]

- ^ Groce, Nora Ellen (24 November 2016). "Deafness on Martha's Vineyard". Britannica.

- ^ Gracer, Bonnie (15 April 2003). "What the Rabbis Heard: Deafness in the Mishnah". Disability Studies Quarterly. 23 (2). doi:10.18061/dsq.v23i2.423.

- ^ Ferreri, Giulio (1906). "The deaf in antiquity". American Annals of the Deaf. 51 (5): 460–473. JSTOR 44463121.

- ^ Bonet, Juan Pablo (1992). Reducción de las letras y arte para enseñar a hablar a los mudos [Reduction of letters and art to teach the mute to speak] (PDF) (in Spanish). CEPE. ISBN 978-84-7869-071-8.[page needed]

- ^ Edwards, R. A. R. (2012). Words Made Flesh. doi:10.18574/nyu/9780814722435.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-8147-2243-5.[page needed]

- ^ "Session 2A".

- ^ "Oral Education as Emancipation".

- ^ "21st International Congress on the Education of the Deaf (ICED) in July 2010 in Vancouver, Canada". 10 January 2011.

- ^ "Hands & Voices :: Communication Considerations".

- ^ Hall, Wyatte C. (May 2017). "What You Don't Know Can Hurt You: The Risk of Language Deprivation by Impairing Sign Language Development in Deaf Children". Maternal and Child Health Journal. 21 (5): 961–965. doi:10.1007/s10995-017-2287-y. PMC 5392137. PMID 28185206.

- ^ Goldin-Meadow, Susan; Mayberry, Rachel I. (November 2001). "How Do Profoundly Deaf Children Learn to Read?". Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 16 (4): 222–229. doi:10.1111/0938-8982.00022. S2CID 1578483.

External links

[edit]- History of sign language in the United States (American School for the Deaf Website).

- History of the Royal National Institute for Deaf People (sign language in the UK).

- American Sign Language (ASL) History Lesson

- Pablo Bonet, J. de (1620) Reduction de las letras y Arte para enseñar á ablar los Mudos, Biblioteca Digital Hispánica (BNE).

- First Complete Sign Language Bible