Franz Rosenzweig

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Hebrew. (November 2018) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Franz Rosenzweig | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 25 December 1886 |

| Died | 10 December 1929 (aged 42) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Continental philosophy Existentialism |

Main interests | Theology, philosophy, German idealism, philosophy of religion |

Notable ideas | Star of Redemption |

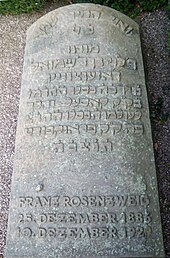

Franz Rosenzweig (/ˈroʊzən.zwaɪɡ/; German: [ˌfʁant͡s ˈʁoːzn̩ˌt͡svaɪ̯k] ; 25 December 1886 – 10 December 1929) was a German theologian, philosopher, and translator.

Early life and education

[edit]Franz Rosenzweig was born in Kassel, Germany, to an affluent, minimally observant Jewish family. His father owned a factory for dyestuff and was a city council member. Through his granduncle, Adam Rosenzweig, he came in contact with traditional Judaism and was inspired to request Hebrew lessons when he was around 11 years old.[1] He started to study medicine for five semesters in Göttingen, Munich, and Freiburg. In 1907 he changed subjects and studied history and philosophy in Freiburg and Berlin.

Rosenzweig, under the influence of his colleague and close friend Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, considered converting to Christianity. Determined to embrace the faith as the early Christians did, he resolved to live as an observant Jew first, before becoming Christian. After attending Yom Kippur services at a small Orthodox synagogue in Berlin, he underwent a mystical experience. As a result, he became a baal teshuva.[2] Although he never recorded what transpired, he never again entertained converting to Christianity.

In 1913, he turned to Jewish philosophy. His letters to his cousin and close friend Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, whom he had nearly followed into Christianity, have been published as ‘’Judaism Despite Christianity’'. Rosenzweig was a student of Hermann Cohen, and the two became close. While writing a doctoral dissertation on Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, ‘’Hegel and the State’', Rosenzweig turned against idealism and sought a philosophy that did not begin with an abstract notion of the human.

Later in the decade, Rosenzweig discovered a manuscript apparently written in Hegel’s hand, which he named “The Oldest Systematic Program of German Idealism.”[3] The manuscript (first published in 1917)[4] has been dated to 1796 and appears to show the influence of F. W. J. Schelling and Friedrich Hölderlin.[5] Despite early debate about the authorship of the document, scholars now generally accept that it was written by Hegel, making Rosenzweig’s discovery valuable for contemporary Hegel scholarship.[6]

Career

[edit]The Star of Redemption

[edit]

Rosenzweig's major work is The Star of Redemption (first published in 1921). It is a description of the relationships between God, humanity, and the world, as they are connected by creation, revelation and redemption. If one makes a diagram with God at the top, and the World and the Self below, the inter-relationships generate a Star of David map. He is critical of any attempt to replace actual human existence with an ideal. In Rosenzweig's scheme, revelation arises not in metaphysics but in the here and now. We are called to love God, and to do so is to return to the world, and that is redemption.

Two translations into English have appeared, the most recent by Dr. Barbara E. Galli of McGill University in 2005[7] and by Professor William Wolfgang Hallo in 1971.[8]

Collaboration with Buber

[edit]Rosenzweig was engaged critically with the Jewish Zionist scholar Martin Buber. The two exchanged letters on the subject of a lecture series which Buber had given. In 1923, one of the letters was published by Rosenzweig as an open letter entitled "The Builders".[9]

Unlike Buber, Rosenzweig felt that a return to Israel would embroil the Jews into a worldly history that they should eschew. Rosenzweig criticized Buber's dialogical philosophy because it is based not only on the I-Thou relation but also on I-It, a notion that Rosenzweig rejected. He thought that the counterpart to I-Thou should be He-It, namely “as He said and it became”: building the "it" around the human "I"—the human mind—is an idealistic mistake.[10] Rosenzweig and Buber worked together on a translation of the Tanakh, or Hebrew Bible, from Hebrew to German. The translation, while contested, has led to several other translations in other languages that use the same methodology and principles. Their publications concerning the nature and philosophy of translation are still widely read.

Educational activities

[edit]Rosenzweig, unimpressed with the impersonal learning of the academy, founded the House of Jewish Learning in Frankfurt in 1920, which sought to engage in dialogue with human beings rather than merely accumulate knowledge. Many prominent Jewish intellectuals were associated with the Lehrhaus, as it was known in Germany, such as Leo Löwenthal, the liberal rabbi Benno Jacob, historian of medicine Richard Koch, the chemist Eduard Strauß, the feminist Bertha Pappenheim, Siegfried Kracauer, a culture critic for the Frankfurter Zeitung, S.Y. Agnon, who later won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and Gershom Scholem, the founder of modern secular studies of the Kabbalah and Jewish mysticism (some of these intellectuals are also associated with the Frankfurt School of critical theory). In October 1922, Rudolf Hallo took over the leadership of the Lehrhaus. The Lehrhaus stayed open until 1930 and was reopened by Martin Buber in 1933.

Illness and death

[edit]

Rosenzweig suffered from the muscular degenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (also known as motor neurone disease (MND) or Lou Gehrig's disease). Towards the end of his life, he had to write with the help of his wife, Edith, who would recite letters of the alphabet until he indicated for her to stop, continuing until she could guess the word or phrase he intended (or, at other times, Rosenzweig would point to the letter on the plate of his typewriter). They also developed a communication system based on him blinking his eyes.

Rosenzweig's final attempt to communicate his thought, via the laborious typewriter-alphabet method, consisted in the partial sentence: "And now it comes, the point of all points, which the Lord has truly revealed to me in my sleep, the point of all points for which there—". The writing was interrupted by his doctor, with whom he had a short discussion using the same method. When the doctor left, Rosenzweig did not wish to continue with the writing, and he died on the night of 10 December 1929, in Frankfurt, the sentence left unfinished.[11]

Rosenzweig was buried on 12 December 1929. There was no eulogy; Buber read Psalm 73.[12]

After his death, his son Rafael fled Germany for Palestine in 1939. Rosenzweig's library with about 3,000 volumes was to follow him, but the cargo ship was diverted to Tunis during the Second World War. It is now in the National Library of Tunisia, Dâr Al-Kutub Al-Wataniya.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Glatzer, Nahum Norbert, ed. (1962). Franz Rosenzweig. His life and thought. New York: Schocken Books. p. XXXVI-XXXVIII.

- ^ Emil L. Fackenheim (1994). To Mend the World. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-32114-X.

- ^ Geoffrey Hartman, ‘’The Fateful Question of Culture’', Columbia University Press, 1998, p. 164.

- ^ Robert J. Richards, ‘’The Romantic Conception of Life: Science and Philosophy in the Age of Goethe’', University of Chicago Press, 2002, p. 124 n. 21.

- ^ Josephson-Storm, Jason (2017). The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 63–4. ISBN 978-0-226-40336-6.

- ^ Magee, Glenn (2001). Hegel and the Hermetic Tradition. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 84. ISBN 0801474507.

- ^ https://uwpress.wisc.edu/books/2786.htm. Archived 10 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rosenzweig, Franz. Der Stern Der Erlosung [The Star of Redemption]. Trans. William W. Hallo. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. 1971. ISBN 0-03-085077-0.

- ^ "The Builders", in On Jewish Learning, ed. and trans. by Nahum Glatzner (New York, 1955).

- ^ Franz Rosenzweig in Encyclopedia Judaica by Ephraim Meir and Rivka G. Horwitz, Thomson Gale, 2007.

- ^ Nahum N. Glatzer, Franz Rosenzweig: His Life and Thought (New York: Schocken Books, 1961, 2nd edn.), pp. 174–6.

- ^ Maurice Friedman, Martin Buber's Life and Work, page 410 (Wayne State University Press, 1988). ISBN 0-8143-1944-0

- ^ Schneidawind, Julia (2021). "A Diaspora of Books - Franz Rosenzweig's Library in Tunis". Jewish Culture and History. 22 (2): 140–53. doi:10.1080/1462169X.2021.1916706.

Further reading

[edit]- Anckaert, Luc & Casper, Bernhard Moses Casper, Franz Rosenzweig - a primary and secondary bibliography (Leuven, 1990)

- Amir, Yehoyada, "Towards mutual Listening: the Notion of Sermon in Franz Rosenzweig's Philosophy", in: Alexander Deeg, Walter Homolka & Heinz–Günter Schöttler (eds.), "Preaching in Judaism and Christianity" (Berlin, 2008), 113–130

- Amir, Yehoyada, Turner, Joseph (Yossi), Brasser, Martin, "Faith, Truth, and Reason - New Perspectives on Franz Rosenzweig's Star of Redemption" (Karl Alber, 2012)

- Belloni, Claudio, Filosofia e rivelazione. Rosenzweig nella scia dell’ultimo Schelling, Marsilio, Venezia 2002

- Bienenstock, Myriam Cohen face à Rosenzweig. Débat sur la pensée allemande (Paris, Vrin, 2009)

- Bienenstock, Myriam (ed.). Héritages de Franz Rosenzweig. "Nous et les autres" (Paris, éditions de l'éclat, 2011)

- Bowler, Maurice Gerald, "The Reconciliation of Church and Synagogue in Franz Rosenzweig," M.A. Thesis, Sir George Williams University, Montreal, 1973

- Chamiel, Ephraim, The Dual Truth, Studies on Nineteenth-Century Modern Religious Thought and its Influence on Twentieth-Century Jewish Philosophy, Academic Studies Press, Boston 2019, Vol II, pp. 308–332.

- Hans Ehrenberg, Franz Rosenzweig and Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy (Sons for Peace), "Ways of Peace, Lights of Peace", Vol 1 & 2, (Rome: Vatican Press, 1910, New York: Bible Society, 1910).

- Gibbs, Robert, Correlations in Rosenzweig and Levinas (1994)

- Glatzer, Nahum Norbert Essays in Jewish thought (1978)

- Glatzer, Nahum Norbert, Franz Rosenzweig - his life and thought (New York, 1953)

- Guttmann, Isaak Julius. Philosophies of Judaism: the history of Jewish philosophy from biblical times to Franz Rosenzweig (New York, 1964)

- Maybaum, Ignaz Trialogue between Jew, Christian and Muslim (London, 1973)

- Mendes-Flohr, Paul R., German Jews - a dual identity (New Haven, CT, 1999)

- Miller, Ronald Henry Dialogue and disagreement - Franz Rosenzweig's relevance to contemporary Jewish-Christian understanding (Lanham, 1989)

- Putnam, Hilary Jewish philosophy as a guide to life - Rosenzweig, Buber, Levinas, Wittgenstein (Bloomington, IN, 2008)

- Rahel-Freund, Else Die Existenz philosophie Franz Rosenzweigs (Breslau 1933, Hamburg 1959)

- Rahel-Freund, Else Franz Rosenzweig's philosophy of existence - an analysis of The star of redemption (The Hague, 1979)

- Samuelson, Norbert Max, The Legacy of Franz Rosenzweig: Collected Essays (Cornell University Press, 2004)

- Santner, Eric L. The Psychotheology of Everyday Life - Reflections on Freud and Rosenzweig (Chicago, IL, 2001)

- Schwartz, Michal, Metapher und Offenbarung. Zur Sprache von Franz Rosenzweigs Stern der Erlösung(Berlin, 2003)

- Tolone, Oreste. "La malattia immortale. Nuovo pensiero e nuova medicina tra Rosenzweig e Weizsäcker", (Pisa 2008)

- Zohar Mihaely, "Rosenzweig's Critique of Islam and its Value Today", in: Roczniki Kulturoznawcze Vol. 11 No. 2 (2020) pp. 5–34.

External links

[edit]- Arnold Betz's essay on Rosenzweig and The Star of Redemption at Vanderbilt University

- Franz Rosenzweig's Der Stern der Erlösung online (in German)

- Review of The Star of Redemption by Spengler in Asia Times

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Franz Rosenzweig

- Guide to the Papers of Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929) at the Leo Baeck Institute, New York.

- Guide to the Franz Rosenzweig - Martin Buber notebooks at the Leo Baeck Institute, New York.

- 1886 births

- 1929 deaths

- 20th-century German philosophers

- 20th-century German theologians

- 20th-century male writers

- 20th-century translators

- Baalei teshuva

- Existentialist theologians

- German Jewish theologians

- German Orthodox Jews

- German male non-fiction writers

- Jewish existentialists

- Jewish philosophers

- Jewish translators of the Bible

- Philosophers of Judaism

- German translation scholars

- Translators of the Bible into German

- University of Freiburg alumni

- Writers from Kassel

- Deaths from motor neuron disease in Germany