Recreational drug tourism

Recreational drug tourism is travel for the purpose of obtaining or using drugs for recreational use that are unavailable, illegal or very expensive in one's home jurisdiction. A drug tourist may cross a national border to obtain a drug that is not sold in one's home country, or to obtain an illegal drug that is more available in the visited destination. A drug tourist may also cross a sub-national border (from one province, county or state to another) to do the same, as in cannabis tourism, or purchase alcohol or tobacco more easily, or at a lower price due to tax laws or other regulations.

Empirical studies show that drug tourism is heterogeneous and might involve either the pursuit of mere pleasure and escapism or a quest for profound and meaningful experiences through the consumption of drugs.

Drug tourism has many legal implications, and persons engaging in it sometimes risk prosecution for drug smuggling or other drug-related charges in their home jurisdictions or in the jurisdictions they are visiting, especially if they bring their purchases home rather than using them abroad. The act of traveling for the purpose of buying or using drugs is itself a criminal offense in some jurisdictions.

By country/region

[edit]India

[edit]Malana, India is famous for its production of Indian hashish or so called Malana Cream, attracting foreign tourists. Indian pharmacies also sell many generic drugs at prices far lower than in the US.[1]

Africa

[edit]In some places of north Morocco like Chaouen Cannabis is planted for Hashish production. There is a big attraction for some European and American consumers because of its low price.[2]

Europe

[edit]

In Europe, the Netherlands, and especially the Dutch capital, Amsterdam, is a popular destination for drug tourists, due to the liberal attitude of the Dutch toward cannabis use and possession. Drug tourism thrives because legislation controlling the sale, possession, and use of drugs varies dramatically from one jurisdiction to another.

Netherlands

[edit]

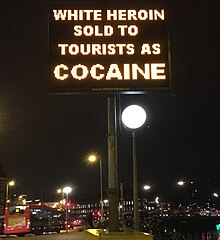

In May 2011, the Dutch government announced that tourists would to be banned from Dutch coffeeshops, starting in the southern provinces at the end of 2011,[3] and the rest of the country by 2012,[4] though this was never made into law and thus coffeeshops throughout the Netherlands continue remain open to tourists as of May 2016.[5] On 25 November 2014 two British tourists aged 20 and 21 died in a hotel room in Amsterdam, after snorting white heroin that was sold as cocaine by a street dealer.[6] The bodies were found less than a month after another British tourist died in similar circumstances. At least 17 other people have had medical treatment after taking the white heroin.[7]

North America

[edit]Drug tourism from the United States occurs in many contexts. Americans between the ages of 18 and 21 may cross the border into Canada or Mexico to purchase alcohol legally. Conversely, many Canadians travel to the United States to purchase alcohol at lower prices due to high taxes levied on alcohol in Canada. Americans living in dry counties also frequently cross county or state lines to purchase alcohol. Due to the fact that cannabis is now legal in Canada, Americans may cross the border to purchase it legally. Many US states also have legal cannabis, many Americans cross state lines to purchase legal cannabis to bring back.

Many Americans cross state lines to purchase cigarettes, crossing from a jurisdiction with very high cigarette taxes to a jurisdiction (such as another state or an Indian nation) with lower cigarette taxes. This occurs particularly in the Northeastern United States, where states levy among the highest tobacco taxes in the nation.

Canada

[edit]As of October 2018, Cannabis consumption and possession in limited amounts is legal in Canada.

United States

[edit]Since the legalization of Cannabis in Alaska, Arizona, California, Connecticut, Colorado, Delaware, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nevada, Montana, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, Washington state and Washington D.C, many drug tourists from states and countries where cannabis is illegal travel to these states to purchase cannabis and cannabis products. [citation needed]

Mexico

[edit]The sale and possession of psilocin and psilocybin are prohibited under the federal health law of 1984. However, this prohibition is mostly unenforced against indigenous users of psilocybin mushrooms. As a result, the towns of Huautla de Jiménez and San José del Pacífico (both in the southern state of Oaxaca) have gained notoriety for their association with magic mushrooms, and constitute a safe haven even for non-indigenous users.

South America

[edit]In South America, some tourists are attracted to Amazon basin villages to try a local religious sacrament called ayahuasca, which is a mixture of psychedelic plants that is used in traditional ceremonies. Similarly, tourists in Peru try hallucinogenic cactus called San Pedro which originally has been used by local tribes.

Bolivia

[edit]Route 36 is an illegal after-hours lounge in La Paz, Bolivia, and, according to The Guardian, the world's first cocaine bar.[8] Although cocaine, an addictive stimulant derived from the coca plant, is illegal in Bolivia, political corruption and affordability of locally produced cocaine have resulted in Route 36 becoming a popular destination for thousands of drug tourists each year.

Colombia

[edit]Colombia's reputation as the cocaine capital of the world has attracted tourists, to the dismay of locals. In Medellín, a small industry has grown around sites related to Pablo Escobar. Drug dealers are cashing in too, selling cocaine to visitors at prices much cheaper than their homelands. There are also “make your own cocaine” tours in parts of the country; however they are highly illegal.[9]

Oceania

[edit]In Australia, the Australian Capital Territory and South Australia have a more liberal approach to cannabis use, promoting interstate drug tourism, particularly from Victoria and New South Wales. In addition, some areas of northern New South Wales have a liberal recreational drug culture, particularly areas around Nimbin where the annual MardiGrass festival is held. Discreet Local Guides may also be a source of plants.

See also

[edit]- Drug policy of the Netherlands

- Recreational drug use

- Route 36 (bar), the world's first cocaine bar in Bolivia

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Specialty Drug Classes That Are Costing Consumers an Arm and a Leg". The Motley Fool. 2015-10-24. Retrieved 2015-10-25.

- ^ El Mundo (In Spanish). Hashish Christmas: This Is the Cannabis Tourism from Madrid to Rif.

- ^ Tourists Face Weed Ban In Dutch Coffee Shops, Sky News, May 28, 2011

- ^ Tourists to be banned from Dutch cannabis cafes, NY Daily News, November 14, 2011 ,

- ^ Many coffeeshops in the Netherlands are still open to tourists. Find one you like.

- ^ Drugs expert claims rogue dealer caused Amsterdam deaths BBC.co.uk

- ^ British tourists who died ‘after snorting white heroin’ named The Guardian

- ^ Franklin, Jonathan (August 19, 2009). "The world's first cocaine bar". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on January 12, 2017. Retrieved August 20, 2009.

- ^ Vorobyov, Niko (2019) Dopeworld. Hodder, UK. p. 187-195

References

[edit]- Belhassen, Y., Santos, C.A., & Uriely, N. (2007). “Cannabis Use in Tourism: A Sociological Perspective.” Leisure Studies, 26(3), 303–19.

- Bellis, M. A., Hale, G., Bennett, A., Chaudry, M. & Kilfoyle, M. (2000). "Ibiza Uncovered: Changes in Substanceuse and Sexual Behaviour amongst Young People Visiting an International Night-Life Resort." International Journal of Drug Policy, 11(3), 235–44.

- De Rios, M. (1994). "Drug Tourism in the Amazon: Why Westerners are Desperate to Find the Vanishing Primate." Omni 16, 6–9.

- Josiam, M. B, J. S. P. Hobson, U. C. Dietrich, & G. Smeaton (1998). “An Analysis of the Sexual, Alcohol and Drug Related Behavioral Patterns of Students on Spring Break.” Tourism Management, 19 (6), 501–13.

- Sellars, A. (1998). “The Influence of Dance Music on the UK Youth Tourism Market.” Tourism Management, 19 (6), 611–15.

- Uriely, N. & Belhassen, Y. (2005). “Drugs and Tourists’ Experiences.” Journal of Travel Research, 43(3), 238–46.

- Uriely, N. & Belhassen, Y. (2006) “Drugs and Risk Taking in Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research, 33(2), 339–59.

- Valdez, A., & Sifaneck, S. (1997). "Drug Tourists and Drug Policy on the U.S.-Mexican Border: An Ethnographic Investigation." Journal of Drug Issues, 27, 879–98.