Balkan sworn virgins

Balkan sworn virgins (in Albanian: burrnesha) are women who take a vow of chastity and live as men in patriarchal northern Albanian society, Kosovo and Montenegro. To a lesser extent, the practice exists, or has existed, in other parts of the western Balkans, including Bosnia, Dalmatia (Croatia), Serbia and North Macedonia.[1]

In times when women had a prescribed role, burrnesha gave up their sexual, reproductive and social identities to acquire the same freedoms as men. They could dress as men, be head of the household, move freely in social situations, and take work traditionally open only to men.[2] National Geographic's Taboo estimated in 2002 that there were fewer than 102 Albanian sworn virgins left.[3] As of 2022[update], while there were no exact figures, twelve burrnesha were estimated to remain in Northern Albania and Kosovo.[2]

| History of Albania |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

Terminology

[edit]Other terms for a sworn virgin include, in English, Albanian virgin or avowed virgin; in Albanian: burrnesha, vajzë e betuar (most common today, and used in situations in which the parents make the decision when the person is a baby or child), and various words cognate with "virgin" – virgjineshë, virgjereshë, verginesa, virgjin, vergjinesha;[4] in Bosnian: tobelija (bound by a vow);[5] in Serbo-Croatian: virdžina; in Serbian: ostajnica (she who stays); in Turkish: sadik, meaning "loyal, devoted".[4]

Origins

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Albanian tribes |

|---|

|

The tradition of sworn virgins in Albania developed out of the Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjinit (English: The Code of Lekë Dukagjini, or simply the Kanun),[6] a set of codes and laws developed by Lekë Dukagjini and used mostly in northern Albania and Kosovo from the Ottoman era until the 20th century. The Kanun is not a religious document; many groups follow it, including Albanian Orthodox, Catholics and Muslims.[7]

The Kanun dictates that families must be patrilineal (meaning wealth is inherited through a family's men) and patrilocal (upon marriage, a woman moves into the household of her husband's family).[8] Women are treated like property of the family. Under the Kanun, women are stripped of many rights. They cannot smoke, wear a watch, or vote in local elections. They cannot buy land, and there are many jobs they are not permitted to hold. There are also establishments that they cannot enter.[7][9]

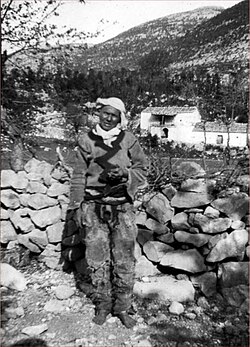

The practice of sworn virginhood was first reported by missionaries, travelers, geographers and anthropologists, who visited the mountains of northern Albania in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[10] One of them was Edith Durham, who took the accompanying photograph.

Overview

[edit]A person can become a sworn virgin at any age, out of personal desire, to avoid forced marriage, or to satisfy familial obligations.[11] One becomes a sworn virgin by swearing an irrevocable oath, in front of twelve village or tribal elders, to adopt the role and practice celibacy. After this, sworn virgins live as men and others relate to them as such, usually though not always[12] using masculine pronouns to address them or speak about them to other people.[13] In Slavic languages with three grammatical genders, they are never spoken about in the third gender.[14] Sworn virgins may dress in male clothing, use a male name, carry a gun, smoke, drink alcohol, take on male work, act as the head of a household (for example, living with a sister or mother), play music, sing, and sit and talk socially with men.[9][10][12] Sworn virgins occupy a formal, socially defined masculine role.[15] The New York Times referred to the practice as "a centuries-old tradition in which women declared themselves men so they could enjoy male privilege".[16]

According to Marina Warner, the sworn virgin's "true sex will never again, on pain of death, be alluded to either in [his] presence or out of it."[17] Similar practices occurred in some societies of indigenous peoples of the Americas.[10]

Breaking the vow was once punishable by death, but it is doubtful that this punishment is still carried out.[9] Many sworn virgins today still refuse to go back on their oath because their community would reject them for breaking the vows.[9] However, it is sometimes possible to take back the vows if the reasons or motivations or obligations to family which led to taking the vow no longer exist.[citation needed]

Motivations

[edit]There are many reasons why someone might take this vow, and observers recorded a variety of motivations. One person spoke of becoming a sworn virgin in order to not be separated from his father, and another in order to live and work with a sister. Some hoped to avoid a specific unwanted marriage, and others hoped to avoid marriage in general; becoming a sworn virgin was also the only way for families who had committed children to an arranged marriage to refuse to fulfil it, without dishonouring the groom's family and risking a blood feud.

It was the only way a woman could inherit her family's wealth, which was particularly important in a society in which blood feuds (gjakmarrja) resulted in the deaths of many male Albanians, leaving many families without male heirs. (However, anthropologist Jeffrey Dickemann suggests this motive may be "over-pat", pointing out that a non-child-bearing woman would have no heirs to inherit after her, and also that in some families not one but several daughters became sworn virgins, and in others the later birth of a brother did not end the sworn virgin's masculine role.[12]) Moreover, a child may have been desired to "carry on" an existing feud, according to Marina Warner. The sworn virgin became "a warrior in disguise to defend [his] family like a man."[17] If a sworn virgin was killed in a blood feud, the death counted as a full life for the purposes of calculating blood money, rather than the half-life a woman was counted as.[18]

It is also likely that many people chose to become sworn virgins simply because it afforded them much more freedom than would otherwise have been available in a patrilineal culture in which women were secluded, sex-segregated, required to be virgins before marriage and faithful afterwards, betrothed as children and married by sale without their consent, continually bearing and raising children, constantly physically labouring, and always required to defer to men, particularly their husbands and fathers, and submit to being beaten.[7][10][12][19]

Dickemann suggests mothers may have played an important role in persuading children to become sworn virgins. A widow without sons traditionally had few options in Albania: she could return to her birth family, stay on as a servant in the family of her deceased husband, or remarry. With a son or surrogate son, she could live out her life in the home of her adulthood, in the company of her child. Murray quotes testimony recorded by René Gremaux: "Because if you get married I'll be left alone, but if you stay with me, I'll have a son." On hearing those words the daughter Djurdja "threw down her embroidery" and became a man.[12]

Prevalence

[edit]The practice has died out in Dalmatia and Bosnia, but is still carried out in northern Albania and to a lesser extent in North Macedonia.[10]

The Socialist People's Republic of Albania did not encourage people to become sworn virgins. Women started gaining legal rights and came closer to having equal social status, especially in the central and southern regions. It is only in the northern region that many families are still traditionally patriarchal.[20] In 2008, there were between forty and several hundred sworn virgins left in Albania, and a few in neighboring countries, most over fifty years old,[7] with an estimated twelve left in 2022.[2] It used to be believed that the sworn virgins had all but died out after 50 years of communism in Albania, but recent research suggests that may not be the case;[10] instead, the increase in feuding following the collapse of the communist regime could encourage a resurgence of the practice.[12]

In popular culture

[edit]- Virdžina (1991), a Yugoslav drama film based on this old custom, directed by Srđan Karanović.[21][22]

- In "The Albanian Virgin" (1994[23]), a short story by Alice Munro first published in The New Yorker, a Canadian woman being held hostage by Albanians takes the vow to avoid forced marriage. (For information about documented kidnappings, see Ion Perdicaris and the Miss Stone Affair.)

- Italian director Laura Bispuri's first feature film, Sworn Virgin (2015), depicts the life of Hana, played by Italian actress Alba Rohrwacher.[24] The film is based on the novel of the same name by Albanian writer Elvira Dones.[9] There are centuries-old Albanian communities in Italy.

Noted sworn virgins

[edit]- Stana Cerović

- Mikaš Karadžić

- Tone Bikaj

- Durdjan Ibi Glavola

- Stanica-Daga Marinković[25]

See also

[edit]- Samsui women, a similar practice among Chinese diaspora women in Southeast Asia

- Bacha posh, a similar practice in Afghanistan and Pakistan

- Vestal Virgin

- Honorary male

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Stana Cerović, poslednja crnogorska virdžina" [Stana Cerović, the last Montenegrin virgin] (in Serbian). National Geographic Serbia. 28 June 2016. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016.

- ^ a b c McLean, Tui (10 December 2022). "The last of Albania's 'sworn virgins'". BBC News.

- ^ "National Geographic's Taboo". natgeo.com. Archived from the original on 2010-01-17. Retrieved 2009-11-11. (trailer: "Taboo S1E9: Sexuality (Documentary)" (video 1h 36'). National Geographic – via YouTube.)

- ^ a b Young, Antonia (December 2010). ""Sworn Virgins": Cases of Socially Accepted Gender Change". Anthropology of East Europe Review: 59–75. Archived from the original on 2016-09-27. Retrieved 2015-12-03.

- ^ "MONTENEGRINA - digitalna biblioteka crnogorske kulture i nasljedja". www.montenegrina.net.

- ^ From Turkish Kanun, which means law. It is originally derived from the Greek kanôn (κανών) as in canon law,

- ^ a b c d Becatoros, Elena (October 6, 2008). "Tradition of sworn virgins' dying out in Albania". Die Welt. Archived from the original on October 26, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ "Crossing Boundaries:Albania's sworn virgins". jolique. 2008. Archived from the original on 18 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ^ a b c d e Zumbrun, Joshua (August 11, 2007). "The Sacrifices of Albania's 'Sworn Virgins'". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ^ a b c d e f Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Albania (2nd ed.). Lanham: Scarecrow Press. p. 435. ISBN 978-0810861886.

- ^ Magrini, Tullia, ed. (2003). Music and Gender: Perspectives from the Mediterranean. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 294. ISBN 0226501655.

- ^ a b c d e f Murray, Stephen O.; Roscoe, Will; Allyn, Eric (1997). Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History, and Literature. New York: New York University Press. pp. 198 and 201. ISBN 0814774687.

- ^ Andreas Hemming, Gentiana Kera, Enriketa Pandelejmoni, Albania: Family, Society and Culture in the 20th Century (2012, ISBN 3643501447), page 168: Others relate to them as men, usually using male pronouns both in addressing them and in speaking of them.

- ^ Grémaux, René (1996). "Woman Becomes Man in the Balkans". In Herdt, Gilbert (ed.). Third Sex Third Gender: Beyond sexual dimorphism in culture and history (1st (2020) ebook ed.). New York: Zone Books. p. 277. ISBN 0-942299-82-5.

- ^ Zimmerman, Bonnie (2000). "Balkan Sworn Virgin". Lesbian Histories and Cultures: An Encyclopedia. p. 91. ISBN 9780815319207.

Traditional European female-to-male transgender. The Balkan sworn virgin is a traditional status, role, and identity by which genetic females become social men, the only such socially recognized transgendered status in modern Europe. Clover (1986) proposed that this may be a survival of a more widespread pre-Christian European status.

- ^ "With More Freedom, Young Women in Albania Shun Tradition of 'Sworn Virgins'". The New York Times. 2021-08-08. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ a b Warner, Marina (1994). "Boys Will Be Boys: The Making of the Male". Six Myths of Our Time: Little Angels, Little Monsters, Beautiful Beasts, and More. New York: Vintage. pp. 45. ISBN 0-679-75924-7.

- ^ Anderson, Sarah M.; Swenson, Karen, eds. (2002). Cold Counsel: Women in Old Norse Literature and Mythology: A collection of essays. New York: Routledge. p. 50. ISBN 0815319665.

- ^ Wolman, David (January 6, 2008). "'Sworn virgins' dying out as Albanian girls reject manly role". London: TimesOnline. Archived from the original on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-08.

- ^ "At home with Albania's last sworn virgins". The Sydney Morning Herald. June 27, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-07.

- ^ Virzina (Sworn Virgin) on IMDB

- ^ Canby, Vincent (19 October 2022). "Reviews/Film Festival; A Girl Who Becomes a Boy, and Then a Woman". The New York Times.

- ^ Munro, Alice (20 June 1994). "The Albanian Virgin". Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- ^ "Powerful film debut shows awakening of an Albanian 'Sworn Virgin'". Reuters. February 12, 2015. Retrieved 2015-05-03.

- ^ "Fondacija CURE - VIRDŽINA - ŽENA KOJE NEMA". www.fondacijacure.org.

References

[edit]- Littlewood, Roland; Young, Antonia (2005). "The Third Sex in Albania: An Ethnographic Note". In Shaw, Alison; Ardener, Shirley (eds.). Changing Sex and Bending Gender. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-84545-053-1.

- Whitaker, Ian (July 1981). ""A Sack for Carrying Things": The Traditional Role of Women in Northern Albanian Society". Anthropological Quarterly. 54 (3). The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research: 146–156. doi:10.2307/3317892. JSTOR 3317892.

Further reading

[edit]- Horváth, Aleksandra Djajic (2003). "A tangle of multiple transgressions: The western gaze and the Tobelija (Balkan sworn-virgin-cross-dressers) in the 19th and 20th centuries". Anthropology Matters Journal. 5 (2).

- Munro, Alice (1994), "The Albanian Virgin," a piece of short fiction in the collection Open Secrets. ISBN 0-679-43575-1

- Dukes, Kristopher (2017), "The Sworn Virgin," a historical fiction novel about the tradition. ISBN 978-0-062660-74-9

- Young, Antonia (2000). Women Who Become Men: Albanian Sworn Virgins. ISBN 1-85973-335-2

External links

[edit]- Albanian Custom Fades: Woman as Family Man by Dan Bilefsky, 2008

- Photographs by Jill Peters, 2012

- Photographs by Johan Spanner, The New York Times, 2008

- Photographs by Pepa Hristova, German Society for Photography, 2009

- BBC radio show on sworn virgins

- Sworn Virgins – National Geographic Film (approx. 4 min.)

- BBC From Our Own Correspondent 02/09