Practice Essentials

Septic thrombophlebitis is a clinical syndrome resulting from an infectious source at the site of a venous occlusion with a subsequent systemic inflammatory response. Most commonly seen in peripheral or pelvic veins, SVC, IJ, portal veins, or dural sinus.

Signs and Symptoms

Patients may present with various symptoms dependent on the occlusion site including pain, swelling, fever, erythema, purulent drainage, etc. In severe cases, this can result in distributive shock, sometimes with an unclear source on a physical exam if the involvement of the deep veins is the cause. Signs and symptoms include the following:

-

Pain

-

Fever

-

Swelling

-

Purulent drainage

-

Cellulitis

-

Abscess

-

Shock

Whereas the previously described signs and symptoms are a generalized demonstration of what might occur, the following represents a clinical syndrome associated with a specific location of thrombophlebitis.

Signs and symptoms of Lemierre syndrome [1, 2] include the following:

-

Fever

-

Oropharyngeal pain/erythema

-

Exudative tonsilitis

-

Pharyngeal pseudomembranes

-

Tenderness/swelling/pain over the jaw

-

Pharyngitis

-

Tenderness and induration along the sternocleidomastoid

-

Dysphonia

-

Ipsilateral vocal cord paralysis

Signs and symptoms of dural sinus thrombophlebitis include the following:

-

Fever

-

Ptosis, proptosis, chemosis

-

Extraocular palsies

-

Abnormal fundoscopic exam

-

Nuchal rigidity

-

Seizure

-

Focal neurological deficit

-

Elevated ICP

-

Transient visual obscurations

-

Optic nerve edema

Signs and symptoms of pelvic thrombophlebitis include the following:

-

Fever

-

Pelvic/abdominal/flank pain

Signs and symptoms of pylephlebitis include the following:

-

Fever

-

Jaundice

-

Abdominal pain

-

Hepatomegaly

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of septic thrombophlebitis relies on identifying a clinical syndrome associated with an inflammatory response and localization to a particular vascular territory. In the cases of deeper venous system involvement, a clear source often is not identified, and imaging is necessary to determine the source.

The best available test is the CT scan with IV contrast to evaluate for filling defects that may contain a clot and suggest a nidus for infection. Additionally, MRI is as specific but less sensitive for the diagnosis, and finally, ultrasound can be used, which is less sensitive but as specific. Additional laboratory tests include the following:

-

Blood cultures

-

Wound culture (from suppurative lesions)

-

Catheter tip culture

-

CBC, blood chemistries including LFT, PT/INR, and CSF cultures.

Management

Treatment generally depends on the site of STP, the organisms involved, and the cause. The main goals include the removal of the infective source, antibiotic coverage, possible anticoagulation, and evaluation for surgical intervention.

-

Remove catheters that are placed distally to a site of thrombosis.

-

Broad-spectrum antibiotics against gram-positive organisms with possible MRSA coverage dependent on risk factors. Generally, Vancomycin or cephalosporins are used. Duration can be as short as 7 days in uncomplicated cases.

-

In the cases of fungal growth, sometimes associated with the use of TPN in immunocompromised hosts, antifungal coverage is recommended.

-

Additional coverage against gram-negative organisms or even aerobic/anaerobic organisms as in the case with Lemierre Syndrome.

-

Associated abscesses should be drained and surgical resection of the involved vein and its emissaries is definitive treatment when antibiotics alone are insufficient. Larger veins that are not amenable to surgical resection are treated conservatively with antibiotics alone.

-

The role of anticoagulation is uncertain and should be done so in conjunction with a multidisciplinary team including infectious disease, vascular surgery, and hematology.

Background

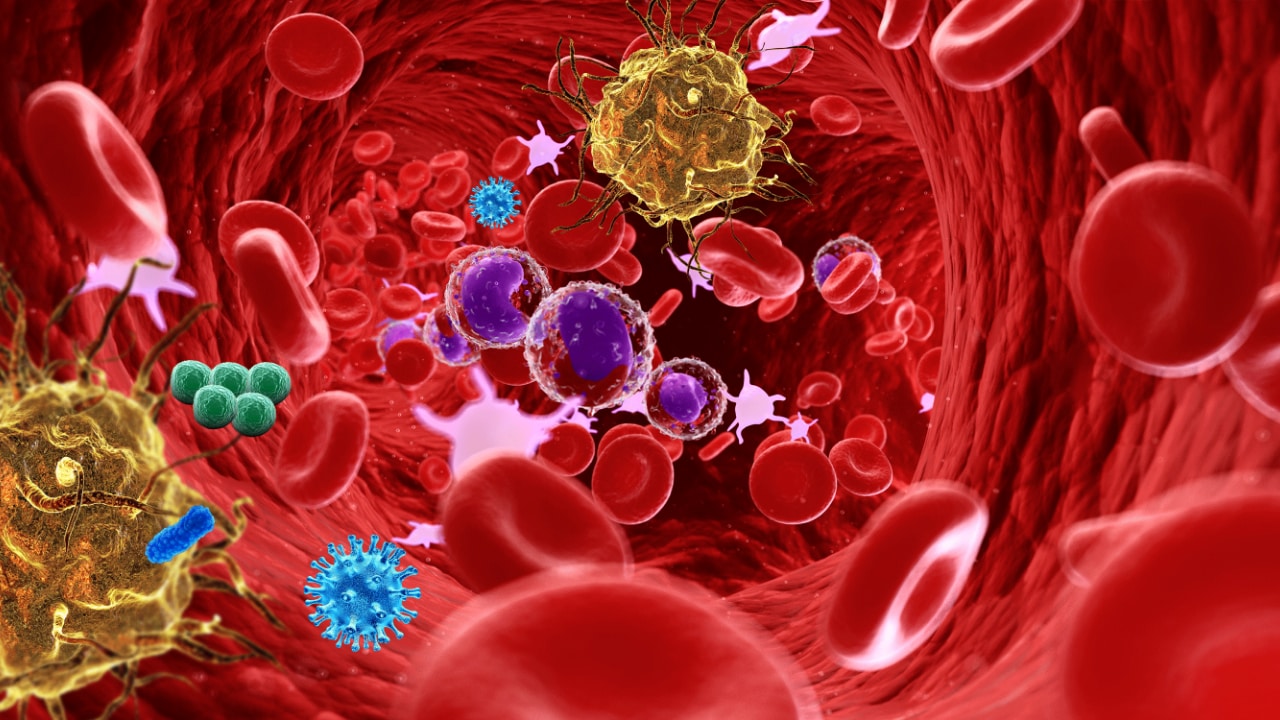

Septic thrombophlebitis is a condition characterized by venous thrombosis, inflammation, and bacteremia or fungemia. [3] The clinical course and severity of septic thrombophlebitis are quite variable. Many cases present as benign, localized venous cords that resolve completely with minimal intervention, however other cases present as severe systemic infections culminating in profound shock that is refractory to aggressive management, including operative intervention and intensive care.

A number of distinct clinical conditions have been identified, depending on the vessel involved, but all thrombophlebitides involve the same basic pathophysiology. Thrombosis and infection within a vein can occur throughout the body and can involve superficial or deep vessels. Notable examples are thrombophlebitis in the following:

-

Peripheral veins

-

Pelvic veins

-

Portal vein (pylephlebitis)

-

Superior vena cava (SVC) or inferior vena cava (IVC)

-

Internal jugular vein (Lemierre syndrome)

-

Dural sinuses

Sites of septic thombophlebitis are in part explained by Virchow's triad (the conditions leading to thrombus): venous stasis, hypercoagulability, and inflammation. Some of the more common sites of septic thrombophlebitis that are more prone to venous stasis or local inflammation due to adjecent infection are explained by anatomy. [4] The approach to treatment of septic phlebitis depends on which structures are involved, the underlying etiology of the phlebitis, the causative organisms, and the patient's underlying physiology.

Peripheral septic thrombophlebitis is a common problem that can develop spontaneously but more often is associated with breaks in the skin. Though most commonly caused by indwelling catheters, septic thrombophlebitis also may result from simple procedures such as venipuncture for phlebotomy and intravenous injection. Infection must always be considered; however, catheter-related phlebitis can result from sterile chemical or mechanical irritation.

Septic phlebitis of a superficial vein without frank purulence is known as simple phlebitis. Simple phlebitis often is benign, but when it is progressive, it can cause serious complications, and even death.

Suppurative superficial thrombophlebitis is a more serious condition that can lead to sepsis and death, even with appropriate aggressive intervention. [5] A frequent complication is embolization of infected thrombus to distant sites, most commonly the lungs, leading to septic pulmonary emboli, hypoxia, sepsis, and often death. [6] Patient factors such as burns, [7] steroid usage, [8] or intravenous drug use [6] increase the risk of developing septic phlebitis and its complications.

Septic phlebitis of the deep venous system is a rare, but life-threatening, emergency that may fail to respond to even the most aggressive therapy. Any vessel theoretically be involved, but the more common entities are detailed below.

Septic thrombophlebitis of the IVC or SVC is primarily the result of central venous catheter placement, with increased incidence in burn patients and those receiving total parenteral nutrition. [9] Patients are generally very ill appearing with high fever, and they also may have signs of venous occlusion, including arm and neck edema. The mortality rate of these infections is high, but cases of successful treatment have been reported. [9]

Lemierre syndrome is a suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein caused by oropharyngeal infections such as tonsillitis and dental infections. [1, 2] Spread of the infection into the parapharyngeal space that houses the carotid sheath leads to local inflammation and thrombosis of the jugular vein. Lemierre syndrome is easily missed and it is more common than is generally appreciated. [10, 11] Unlike superficial vein thrombophlebitis, septic pulmonary emboli nearly always are present and lead to grave complications such as empyema, lung cavitation, and hypoxemia. Less commonly, septic emboli may traverse a patent foramen ovale and cause distant metastatic infections such as septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and hepatic abscesses. [12]

Septic pelvic thrombophlebitis and ovarian vein thrombophlebitis are seen principally as a complication of puerperal uterine infections, such as endometritis and septic abortion. [13, 14] Rarely, pelvic phlebitis may result from severe pelvic inflammatory disease or progressive infection of the urinary tract. In abdominal infections, such as appendicitis and diverticulitis, an infection may spread to cause neighboring septic phlebitides.

Thrombophlebitis of the intracranial venous sinuses is a particularly morbid problem and can involve the cavernous sinus, the lateral sinus, or the superior sagittal sinus. Cavernous sinus thrombophlebitis is caused by infection of the medial third of the face known as the "danger zone," ethmoid and sphenoid sinusitis, and, occasionally, oral infections. Mastoiditis and otitis media rarely are associated with septic phlebitis of the lateral sinuses, while thrombophlebitis of the superior sagittal sinus is the rarest and is primarily associated with meningitis. More than a third of cases of intracranial septic thrombophlebitis are fatal. [15]

Patient education

For patient education information, see Phlebitis.

Etiology

Peripheral, IVC, and SVC phlebitis

Causes include the following:

-

Venipuncture

-

Central and peripheral catheterization

-

Intravenous drug use

-

Abrasions and lacerations

-

Soft-tissue infection

-

Hypercoagulable states

-

Burns

Pelvic, ovarian, and pylephlebitis

Causes include the following:

-

Diverticulitis

-

Endometritis

-

Pelvic inflammatory disease

-

Septic abortion

-

Childbirth

-

Appendicitis

-

Any intra-abdominal infection

-

Cesarean delivery

-

Intra-abdominal surgery

-

Hypercoagulable states

Lemierre syndrome

Causes include the following:

-

Pharyngitis

-

Dental infections

-

Hypercoagulable states

Dural vein thrombophlebitis

Causes include the following:

-

Oropharyngeal infection

-

Mastoiditis

-

Otitis media

-

Facial soft-tissue infections

-

Meningitis

-

Hypercoagulable states

Superficial septic thrombophlebitis

Placement of an intravascular catheter is the main causative factor in the development of phlebitis and septic thrombophlebitis. Infection can be introduced during the placement of the catheter or bacteria can colonize first the hub and then the lumen of the catheter before they gain access to the intravascular space. [16] Once inside the venous system, bacteria can proliferate, causing endothelial damage, local inflammation, and thrombosis.

Causative organisms are diverse and include skin and subcutaneous tissue pathogens, enteric bacteria, and flora causing infection in the genitourinary tract. The most common infective organism is Staphylococcus aureus, but coagulase-negative staphylococci, enteric gram-negative bacilli, and enterococci also are frequently implicated. [17]

Impaired local defense, as well as a heavy burden of skin inoculum, increase burn patients’ susceptibility to thrombophlebitis. These infections are often polymicrobial. [7] Steroid use [8] and injection drug use [6] are other important risk factors.

Deep septic thrombophlebitis

Septic pelvic and ovarian vein thrombophlebitides often are puerperal and typically occur within 3 weeks of delivery. [18] They result from a localized uterine infection, such as endometritis. Damage to the intima of pelvic ileofemoral vessels during vaginal or cesarean delivery is thought to contribute to the process of thrombosis. Hypercoagulability secondary to pregnancy, as well as the venous stasis common in the peripartum state, also contribute. [13] Pathogens responsible for endometritis, such as streptococci, Enterobacteriaceae, and anaerobes, likely are causative, but cultures often are negative.

Septic thrombophlebitis of the portal vein, known as pylephlebitis, is a rare complication of diverticulitis (found to be the inciting infection in 32% of cases). It also may be caused by other intra-abdominal infections drained by or contiguous with the portal vein. [19] Local infection of an adjacent structure can cause extravasation of bacteria and toxin-inducing thrombosis and infection. Bacteroides fragilis is the most common pathogen, but other bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella species, and other Bacteroides species, also are found. [19]

Septic IVC/SVC thrombophlebitis has been found almost exclusively in the setting of central venous catheter placement with the subsequent development of thrombosis, infection, and worsening systemic disease. However, a case report found an IVC filter to be the nidus of a septic phlebitis. [20] In addition to Staphylococcus species, other skin flora and fungal pathogens cause a significant portion of infections. Candida albicans is the most common fungal pathogen, but cases have also been attributed to Candida glabrata. [20]

Lemierre syndrome

Like abdominal and pelvic thrombophlebitis, Lemierre syndrome is characterized by the migration of bacteria through the deep tissues. In this infection, pathogens translocate through the pharynx or are drained from the pharynx into the lateral pharyngeal space, where they come near to the internal jugular vein. Inflammation, thrombosis, and infection may then ensue. [21]

Lemierre syndrome, interestingly, is caused in 80% of patients by Fusobacterium necrophorum, [22] though infections by other pathogens—namely Fusobacterium nucleatum, Bacteroides species, and streptococcal species—have been reported. [12]

Septic thrombosis of the dural venous sinuses

The predisposing infections that ultimately result in septic thrombosis of the dural venous sinuses are closely related to the venous anatomy of the face and head. Infections of the medial third of the face, involving the nose, periorbital regions, tonsils, and soft palate, long have been recognized risk factors, since these areas drain directly into the cavernous sinus via the facial veins, pterygoid plexus, and ophthalmic veins. Infections of the sphenoid and ethmoid sinuses have been implicated, with bacteria spreading directly through the lateral wall or via emissary veins. [15] Mastoiditis, resulting from chronic ear infections, is almost wholly responsible for cases of septic lateral sinus thrombosis. [15]

Extremely rare, septic thrombophlebitis of the superior sagittal sinus is caused by bacterial meningitis, but frontal, ethmoid, and maxillary sinus infections and spread from infections in the lateral dural sinus also have been reported. [15]

The microbiology of intracranial vascular infections depends in large part on the causative infective site. S aureus is by far the most common organism seen in cavernous sinus thrombosis and is responsible for all septic thromboses resulting from facial and sphenoid sinusitis. Streptococci, anaerobes, and (occasionally) fungi also are seen in cavernous sinus thrombosis. [23, 24]

Organisms responsible for superior sagittal sinus thromboses include those responsible for meningitis, notably S pneumoniae, whereas pathogens more representative of chronic otitis, such as Proteus, S aureus, E coli, and anaerobes, were found to cause lateral sinus thrombophlebitis. [15]

Epidemiology

Catheter-associated phlebitis

Catheter-associated bloodstream infection is a common problem well recognized by the hospital community, and major efforts have been made to combat this problem. In 1990, a French study found that 9.9% of patients with peripheral IVs developed signs of phlebitis, whereas 1.1% became purulent. Similar rates have been noted for central venous catheters. [25] Research has shown a rate of 0.5 intravenous device ̶ related bloodstream infections per 1000 intravenous device days for peripheral IV catheters and 2.7 for nontunneled, nonmedicated central venous catheters. [26] Burn patients are at an increased risk, with occurrences of septic thrombophlebitis in 4.2% of these individuals. [7]

Noncatheter septic thrombophlebitis

Given the rarity of pelvic, ovarian, jugular, portal, and dural vein septic thrombophlebitides, epidemiologic data describing their frequency are lacking. In general, however, incidences of these deep vein infections appears to be rising, likely owing in part to the increased use of sophisticated diagnostic imaging. In an epidemiologic survey examining the frequency of septic pelvic thrombophlebitis, an overall incidence of 1:3000 deliveries was found, with cesarean deliveries having an approximately 10-fold increase in incidence over vaginal deliveries. [18]

Lemierre syndrome also is infrequent but is easily missed and likely underdiagnosed. Reports from Europe suggested a rate of 0.8 cases per million per year, [27] though subsequent data pointed to an increase in incidence. [28] Septic thrombophlebitis of the dural sinuses is the most rare, with 96 reported cases in the literature over 44 years. [15]

Age-related demographics

Extremes of age predispose patients to catheter-related septic thrombophlebitis. Bloodstream infections were found to be the cause of as much as 30% of nosocomial infections in neonates with intravenous catheters, [29] with undeveloped host defenses thought to be responsible for this. Vulnerability also is increased in elderly persons, likely secondary to concomitant illnesses and a nonspecific, age-related decline in immunologic function.

Garrison et al reported increased risk for the development of major complications from intravenous catheter placement in patients aged 50 years and older, with an odds ratio of 4.7. [30]

Notable exceptions to the above age-related predispositions are Lemierre syndrome and septic pelvic and ovarian thrombophlebitides: Lemierre disease occurs in healthy, young adults with a mean age of onset of 20 years, [10] whereas septic pelvic and ovarian thrombophlebitides occur in women of childbearing age.

Prognosis

Septic thrombophlebitis is a relatively rare disease that encompasses an array of clinical entities, so data on mortality rates are scarce. Needless to say, it is a serious and dangerous disease, because the infection takes root in the central or peripheral venous system and can readily progress to sepsis and shock.

Metastatic foci of infection are common, with septic pulmonary emboli, infective endocarditis, septic emboli to the central nervous system, osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, and even arteritis all adding to the morbidity and mortality burden of this disease. [17] In fact, major complications occur in about one third of all patients with catheter-associated peripheral septic phlebitis. [17]

Some entities of deep venous thrombosis carry uniquely high mortality rates, with pylephlebitis portending a mortality rate of 32% in one case series of 19 patients. [19] Thrombophlebitis due to Candida species, as seen with central venous catheters, boasts a 22% death rate. [20]

The death rate remains extremely high for patients with septic thrombophlebitis of the intracranial dural sinuses; septic cavernous sinus thrombosis carries a mortality rate of 30%, whereas 78% of patients with infection of the superior sagittal sinus die even with appropriate antibiotic treatment. Serious complications in survivors include ocular palsies, hemiparesis, blindness, and pituitary insufficiency. [15]

Notably, however, pelvic and jugular thrombophlebitis appear to have become less deadly over the years. Early twentieth century data reported a 50% mortality rate in the setting of pelvic thrombophlebitis, whereas one series following more than 44,000 deliveries demonstrated no major complications and not a single death. [18] Lemierre syndrome previously was reported to have a high incidence of mortality; however, with the advent of antibiotics, a meta-analysis of patients from 1980-2017 found the mortality rate was closer to 4.1%. [31]

Pathophysiology

Septic thrombophlebitis (STP) usually occurs as a disruption in the coagulation cascade as a result of endothelium disruption providing a subsequent nidus for infection. The disruption of the vein can occur secondary to catheter insertion but also can happen as an underlying hypercoagulable state such as those with cancer. Once thrombus is present, microorganisms can propagate as a result of direct innoculation or as a hematogenous spread or from adjacent structures. [32]

The most common organism involved in STP is Staph aureus; however, others can be present including viral, fungal, or other types of gram positive, or gram negative species.

Lemierre Syndrome

STP as seen in Lemierre Syndrome is a result of odontogenic infection with subsequent seeding along the carotid sheath. Once a clot is encountered with provides an area for further localized propagation of the innoculating organissm and results in the the clincial syndrome with Lemierre. This typically is caused by anaerobic Fusobacterium necrophorum. [33]

Dural Sinus Thrombosis

infection in the middle third of the face, dubbed "the danger zone" can lead to seeding of bacterial infections secondary to the valveless venous structures of the face. Infections such as orbital cellulitis, tonsilar infections, and sinus infections can cause STP via this route.

Pylephlebitis

Pylephlebitis, infection of a clot found in the portal venous system, is a result of spreading infection from adjacent abdominal structures. [34]