Abstract

Current hypotheses of early tetrapod evolution posit close ecological and biogeographic ties to the extensive coal-producing wetlands of the Carboniferous palaeoequator with rapid replacement of archaic tetrapod groups by relatives of modern amniotes and lissamphibians in the late Carboniferous (about 307 million years ago). These hypotheses draw on a tetrapod fossil record that is almost entirely restricted to palaeoequatorial Pangea (Laurussia)1,2. Here we describe a new giant stem tetrapod, Gaiasia jennyae, from high-palaeolatitude (about 55° S) early Permian-aged (about 280 million years ago) deposits in Namibia that challenges this scenario. Gaiasia is represented by several large, semi-articulated skeletons characterized by a weakly ossified skull with a loosely articulated palate dominated by a broad diamond-shaped parasphenoid, a posteriorly projecting occiput, and enlarged, interlocking dentary and coronoid fangs. Phylogenetic analysis resolves Gaiasia within the tetrapod stem group as the sister taxon of the Carboniferous Colosteidae from Euramerica. Gaiasia is larger than all previously described digited stem tetrapods and provides evidence that continental tetrapods were well established in the cold-temperate latitudes of Gondwana during the final phases of the Carboniferous–Permian deglaciation. This points to a more global distribution of continental tetrapods during the Carboniferous–Permian transition and indicates that previous hypotheses of global tetrapod faunal turnover and dispersal at this time2,3 must be reconsidered.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The authors declare that all the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and the Supplementary Information. All nomenclatural acts are registered with ZooBank (https://zoobank.org) under the Life Science Identifier urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:62D1B947-D36F-49D2-8490-EAD49C46A22B.

References

Clack, J. A. et al. Phylogenetic and environmental context of a Tournaisian tetrapod fauna. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 0002 (2017).

Pardo, J. D., Small, B. J., Milner, A. R. & Huttenlocker, A. K. Carboniferous–Permian climate change constrained early land vertebrate radiations. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 200–206 (2019).

Dunne, E. M. et al. Diversity change during the rise of tetrapods and the impact of the “Carboniferous rainforest collapse”. Proc. R. Soc. B 285, 20172730 (2018).

Olroyd, S. L. & Sidor, C. A. A review of the Guadalupian (middle Permian) global tetrapod fossil record. Earth Sci. Rev. 171, 583–597 (2017).

Benson, R. B. & Upchurch, P. Diversity trends in the establishment of terrestrial vertebrate ecosystems: interactions between spatial and temporal sampling biases. Geology 41, 43–46 (2013).

Pardo, J. D., Lennie, K. & Anderson, J. S. Can we reliably calibrate deep nodes in the tetrapod tree? Case studies in deep tetrapod divergences. Front. Genet. 11, 506749 (2020).

Campbell, K. S. W. & Bell, M. W. A primitive amphibian from the Late Devonian of New South Wales. Alcheringa 1, 369–381 (1977).

Warren, A. & Turner, S. The first stem tetrapod from the Lower Carboniferous of Gondwana. Palaeontology 47, 151184 (2004).

Gess, R. & Ahlberg, P. E. A tetrapod fauna from within the Devonian Antarctic Circle. Science 360, 1120–1124 (2018).

Piñeiro, G., Ferigolo, J., Ramos, A. & Laurin, M. Cranial morphology of the Early Permian mesosaurid Mesosaurus tenuidens and the evolution of the lower temporal fenestration reassessed. C. R. Palevol. 11, 379–391 (2012).

Cisneros, J. C. et al. New Permian fauna from tropical Gondwana. Nat. Commun. 6, 8676 (2015).

Werneburg, R., Schneider, J. W., Voigt, S. & Belahmira, A. First African record of micromelerpetid amphibians (Temnospondyli, Dissorophoidea). J. Afr. Earth. Sci. 159, 103573 (2019).

Stollhofen, H., Stanistreet, I. G., Rohn, R., Holzförster, F. & Wanke, A. in Lake Basins Through Space and Time, Vol. 46 (eds. Gierlowski-Kordesch, E. H. & K. R. Kelts) 87–108 (AAPG, 2000).

Warren, A. A. et al. Oldest known stereospondylous amphibian from the Early Permian of Namibia. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 21, 34–39 (2001).

Santos, R. V. et al. Shrimp U–Pb zircon dating and palynology of bentonitic layers from the Permian Irati Formation, Paraná Basin, Brazil. Gondwana Res. 9, 456–463 (2006).

Chukwuma, K. & Bordy, E. in Origin and Evolution of the Cape Mountains and Karoo Basin (eds Linol, B. & de Wit, M. J.) 101–110 (Springer, 2016).

Carroll, R. L. An adelogyrinid lepospondyl amphibian from the Upper Carboniferous. Can. J. Zool. 45, 1–16 (1967).

Witzmann, F., Scholz, H., Mueller, J. & Kardjilov, N. Sculpture and vascularization of dermal bones, and the implications for the physiology of basal tetrapods. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 160, 302–340 (2010).

Sequeira, S. E. The skull of Cochleosaurus bohemicus Frič, a temnospondyl from the Czech Republic (Upper Carboniferous) and cochleosaurid interrelationships. Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 94, 21–43 (2003).

Damiani, R. et al. The vertebrate fauna of the Upper Permian of Niger. V. The primitive temnospondyl Saharastega moradiensis. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 26, 559–572 (2006).

Lombard, R. E. & Bolt, J. R. A new primitive tetrapod. Whatcheeria deltae, from the Lower Carboniferous of Iowa. Palaeontology 38, 471–494 (1995).

Clack, J. A. & Finney, S. M. Pederpes finneyae, an articulated tetrapod from the Tournaisian of Western Scotland. J. Syst. Paleontol. 2, 311–346 (2005).

Clack, J. A. Two new specimens of Anthracosaurus (Amphibia: Anthracosauria) from the Northumberland coal measures. Palaeontology 30, 15–26 (1987).

Bolt, J. R. & Lombard, R. E. Deltaherpeton hiemstrae, a new colosteid tetrapod from the Mississippian of Iowa. J. Paleontol. 84, 1135–1151 (2010).

Andrews, S. M. & Carroll, R. The order Adelospondyli: Carboniferous lepospondyl amphibians. Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 82, 239–275 (1991).

Milner, A. C. A morphological revision of Keraterpeton, the earliest horned nectridean from the Pennsylvanian of England and Ireland. Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 109, 237–253 (2018).

Pardo, J. D., Szostakiwskyj, M. & Anderson, J. S. Cranial morphology of the brachystelechid ‘microsaur’ Quasicaecilia texana Carroll provides new insights into the diversity and evolution of braincase morphology in recumbirostran ‘microsaurs’. PLoS ONE 10, e0130359 (2015).

Jenkins, F. A. Jr, Shubin, N. H., Gatesy, S. M. & Warren, A. Gerrothorax pulcherrimus from the Upper Triassic Fleming Fjord Formation of East Greenland and a reassessment of head lifting in temnospondyl feeding. J. Vertebr. Paleontol. 28, 935950 (2008).

Ascarrunz, E., Rage, J. C., Legreneur, P. & Laurin, M. Triadobatrachus massinoti, the earliest known lissamphibian (Vertebrata: Tetrapoda) re-examined by μCT scan, and the evolution of trunk length in batrachians. Contrib. Zool. 85, 201–234 (2016).

Clack, J. A. A new baphetid (stem tetrapod) from the Upper Carboniferous of Tyne and Wear, UK, and the evolution of the tetrapod occiput. Can. J. Earth Sci. 40, 483–498 (2003).

Bolt, J. R. & Lombard, R. E. The mandible of the primitive tetrapod Greererpeton, and the early evolution of the tetrapod lower jaw. J. Paleontol. 75, 1016–1042 (2001).

Ahlberg, P. E. & Clack, J. A. The smallest known Devonian tetrapod shows unexpectedly derived features. R. Soc. Open Sci. 7, 192117 (2020).

Downs, J. P., Daeschler, E. B., Jenkins, F. A. & Shubin, N. H. The cranial endoskeleton of Tiktaalik roseae. Nature 455, 925–929 (2008).

Witzmann, F. Phylogenetic patterns of character evolution in the hyobranchial apparatus of early tetrapods. Earth Environ. Sci. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 104, 145–167 (2013).

Pardo, J. D., Szostakiwskyj, M., Ahlberg, P. E. & Anderson, J. S. Hidden morphological diversity among early tetrapods. Nature 546, 642–645 (2017).

Limarino, C. O. et al. A paleoclimatic review of southern South America during the late Paleozoic: a record from icehouse to extreme greenhouse conditions. Gondwana Res. 25, 1396–1421 (2014).

Niedziwiedzki, G., Szrek, P., Narkiewicz, K., Narkiewicz, M. & Ahlberg, P. E. Tetrapod trackways from the early Middle Devonian period of Poland. Nature 463, 43–48 (2010).

Heiss, E., Natchev, N., Gumpenberger, M., Weissenbacher, A. & Van Wassenbergh, S. Biomechanics and hydrodynamics of prey capture in the Chinese giant salamander reveal a high-performance jaw-powered suction feeding mechanism. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20121028 (2013).

Blackburn, T. M., Gaston, K. J. & Loder, N. Geographic gradients in body size: a clarification of Bergmann’s rule. Divers. Distrib. 5, 165–174 (1999).

Simões, T. R., Kammerer, C. F., Caldwell, M. W. & Pierce, S. E. Successive climate crises in the deep past drove the early evolution and radiation of reptiles. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq1898 (2022).

Sahney, S. & Benton, M. J. Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time. Proc. R. Soc. B 275, 759–765 (2008).

Brocklehurst, N., Day, M. O., Rubidge, B. S. & Fröbisch, J. Olson’s Extinction and the latitudinal biodiversity gradient of tetrapods in the Permian. Proc. R. Soc. B 284, 20170231 (2017).

Sidor, C. A. et al. Permian tetrapods from the Sahara show climate-controlled endemism in Pangaea. Nature 434, 886889 (2005).

Milner, A. R. The Westphalian tetrapod fauna; some aspects of its geography and ecology. J. Geol. Soc. 144, 495–506 (1987).

Powell, C. M. & Veevers, J. J. Namurian uplift in Australia and South America triggered the main Gondwanan glaciation. Nature 326, 177–179 (1987).

Fielding, C. R., Frank, T. D. & Isbell, J. L. in Resolving the Late Paleozoic Ice Age in Time and Space Vol. 441 (eds Fielding, C. R. et al.) 343–354 (Geological Society of America, 2008).

Isbell, J. L. et al. Glacial paradoxes during the late Paleozoic ice age: evaluating the equilibrium line altitude as a control on glaciation. Gondwana Res. 22, 1–19 (2012).

Krapovickas, V., Marsicano, C. A., Mancuso, A. C., de la Fuente, M. S. & Ottone, E. Tetrapod and invertebrate trace fossils from aeolian deposits of the lower Permian of central-western Argentina. Hist. Biol. 27, 827–842 (2015).

Boucot, A. J., Xu, C., Scotese, C. R. & Morley, R. J. Phanerozoic Paleoclimate: an Atlas of Lithologic Indicators of Climate Vol. 11 (Society for Sedimentary Geology, 2013).

Swofford, D. L. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods) v4 (Sinauer Associates, 2003).

Goloboff, P. A. Estimating character weights during tree search. Cladistics 9, 83–89 (1993).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Heritage Council and the Geological Survey of Namibia for fieldwork permits and loan of specimens; R. Swart, A. Wanke, F. Abdala and P. October for logistical and field support; S. Mtungata, who found and expertly prepared the type specimen; and G. Lio for the artistic reconstruction of Gaiasia. The 2014, 2015 and 2019 expeditions were supported by National Geographic Society Research Grant 9360-13 and PAST. Research was also possible thanks to the support of the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (Argentina, PICT 2019-01127 to C.A.M.) and the Universidad de Buenos Aires and CONICET (to C.A.M. and L.C.G.). J.D.P. was supported by Banting Postdoctoral Fellowship 473316. This study is contribution R-346 by C.A.M. and L.C.G. to the Instituto de Estudios Andinos Don Pablo Groeber (IDEAN, UBA-CONICET).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived by C.A.M., R.M.H.S. and J.D.P.; phylogenetic analysis was carried out by C.A.M. and J.D.P.; R.M.H.S., C.A.M., A.C.M., L.C.G. and H.M. conducted fieldwork to collect specimens and geological context. C.A.M., J.D.P. and R.M.H.S. wrote the manuscript, with comments from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature thanks Per Ahlberg, Marcello Ruta and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

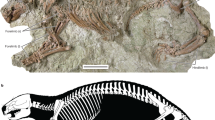

Extended Data Fig. 1 Gaiasia jennyae gen. et sp. nov. (F-1528).

a,b, skull in posterior view. a, Photograph. b, Interpretative drawing. Scale bar, 50 mm. et, excavatio tympanica; exo, exoccipital; occf, occipital artery foramen; op, opisthotic; par, prearticular; psph, parasphenoid; pt, pterygoid; q, quadrate; qj, quadratojugal; sa, surangular;?socc, supraoccipital; X, XII, cranial nerves X and XII, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Gaiasia jennyae gen. et sp. nov. (F-1528).

a,b, Right lateral view of the posterior part of the skull and anterior vertebrae during preparation of the specimen. a, Photograph. b, Interpretative drawing. c,d, Posterior view of the left side of the skull. c, Photograph. d, Interpretative drawing. Scale bar, 50 mm. exo, exoccipital; Md, mandible; occf, occipital artery foramen; op, opisthotic; psph, parasphenoid; pt, pterygoid; q, quadrate; qj, quadratojugal;?socc, supraoccipital; sq, squamosal; X, XII, cranial nerves X and XII, respectively. Yellow shade, spiracular cleft; red shade, depressor mandibulae; cross-hatching, matrix.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Gaiasia jennyae gen. et sp. nov. (F-1528).

a–d, Composite reconstruction of the mandible. a, Dorsal. b, Ventral. c, Labial. d, Lingual. e, f. Photographs of the right hemimandible. e, Ventral view of the posterior half. f, Dorsal view of the symphyseal area. adsym, adsymphysial plate; an, angular; anf, angular fenestra; c1, anterior coronoid; c2, middle coronoid; chf, chordatympanic foramen; d, dentary; par, prearticular; pospl, postsplenial; sa, surangular; spl, splenial. Dotted white circles show the position of the symphysial fangs. Scale bar, 50 mm.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Gaiasia jennyae gen. et sp. nov. (F-1528).

Ventral branchial element in a, Dorsal and b, Ventral views. Anterior to the left. Scale bar, 50 mm.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Gaiasia jennyae gen. et sp. nov. (F-1528).

Articulated axial skeleton. a, Articulated column in right lateral view. Scale bar, 100 mm. b, Detail of the block just behind the star in a. Scale bar, 50 mm. c, Same block as in b in anterior view showing a pleurocentrum. Scale bar, 50 mm. Light green, pleurocentrum; yellow, intercentrum; dark green, neural arch; brown, rib.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Gaiasia jennyae gen. et sp. nov. (F-1528).

a–b, Composite reconstruction of the skull. a, Dorsal. b, Ventral. c, Artistic reconstruction of Gaiasia in lateral view; artwork by Gabriel Lio. ect, ectopterygoid; exo, exoccipital; f, frontal; it, intertemporal; j, jugal; l, lacrimal; mx, maxilla; n, nasal; op, opisthotic; p, parietal; pfr, prefrontal; pl, palatine; pmx, premaxilla; po, postorbital; pof, postfrontal; pp, postparietal; psph, parasphenoid; pt, pterygoid; qj, quadratojugal; socc?, supraoccipital; sq, squamosal; st, supratemporal; t, tabular; v, vomer. Scale bar, 50 mm.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Phylogenetic analysis.

a, Unweighted strict-consensus tree. b—f, Strict consensus of trees recovered using implying weights49. Implied weights inferred with b, k = 2, c, k = 4, d, k = 6, e, k = 8; f, k = 10.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

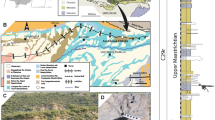

Supplementary Fig. 1 (anatomical figure of paratype specimen), Data including Figs. 2–7 (geological setting and taphonomic information, character list and phylogenetic discussion), Tables 1 and 2 and References.

Supplementary Data

The new phylogenetic dataset generated during the current study.

Supplementary Data

Clack et al. 2019 data matrix.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Marsicano, C.A., Pardo, J.D., Smith, R.M.H. et al. Giant stem tetrapod was apex predator in Gondwanan late Palaeozoic ice age. Nature 631, 577–582 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07572-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-07572-0

This article is cited by

-

Fossils found far from the Equator point to globetrotting tetrapods

Nature (2024)

-

Un fossile de tétrapode géant révise l'époque de l'extinction et élargit la répartition

Nature Africa (2024)

-

Giant tetrapod fossil revises extinction era and broadens range

Nature Africa (2024)