Abstract

Data sources

Medline, PubMed, The Cochrane Library 2010, CINAHL, Embase, seven Korean Medical Databases and a Chinese Medical Database (China Academic Journal, www.cnki.co.kr).

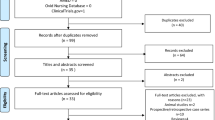

Study selection

Parallel or cross-over RCTs that assessed the efficacy of acupuncture regardless of blinding, language and type of reporting published in English, Chinese and Korean were included. Dissertations and abstracts were included provided they contained sufficient detail. Complex interventions in which acupuncture was not a sole treatment and studies with no reported clinical data were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis

All RCTs were obtained and read in full by two independent reviewers and data extracted according to pre-defined criteria. Quality was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias criteria. Meta-analysis was conducted using random effect models if excessive statistical heterogeneity did not exist. Additional subgroup analysis or sensitivity analysis additionally was conducted to explore heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed by funnel plot using the Cochrane software.

Results

Seven RCTs (including 141 patients) met our inclusion criteria. Six studies comparatively tested needle acupuncture against penetrating sham acupuncture, non-penetrating sham acupuncture or sham laser acupuncture, whilst the remaining study tested laser acupuncture against sham laser acupuncture. Five studies were considered to be at low risk of bias. Outcomes were reported for pain intensity, facial pain, muscle tenderness and mouth opening.

Conclusions

This systematic review produced limited evidence that acupuncture is more effective than sham acupuncture in alleviating pain and masseter muscle tenderness in TMD. Further rigorous studies are, however, required to establish beyond doubt whether acupuncture has therapeutic value for this indication.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

The therapeutic choices for patients suffering from temporomandibular pain (ie, pain located in the masticatory muscles and/or temporomandibular joints) are limited: in clinical trials counseling, relaxation training, stabilisation splints, physical therapy and some pharmacological agents have been shown to be effective. Therefore, any new therapeutic modality with proven efficacy is warmly welcomed.

On the basis of their search, Jung et al. identified seven pertinent study articles. A pooled meta-analysis revealed 'significant improvements in pain intensity' after needle acupuncture. Due to methodological weaknesses inherent to all trials, Jung et al. judge this evidence as being 'limited' and 'weak'.

Interestingly, three other recent systematic reviews on the same topic came to comparable conclusions: La Touche et al. (four studies) noted that the evidence, although limited in amount, showed statistically significant short-term analgesic benefit of acupuncture for masticatory muscle pain.1 Cho and Wang (19 studies) concluded that there was 'moderate evidence that acupuncture is an effective intervention to reduce symptoms associated with TMD'.2 Further subgroup analysis carried out by Jung et al. disclosed that manual acupuncture reduced pain significantly more than non-penetrating sham control. Conversely, no difference in efficacy was seen when penetrating sham acupuncture at non-acupuncture points served as control.

Well-designed randomised controlled studies with more than 40,000 patients diagnosed with tension-type headache, migraine or persistent low back pain support the finding that penetrating sham acupuncture at non-acupuncture points is similarly effective as point-specific 'real' acupuncture. Interestingly, in these large-scale trials, both therapeutic strategies were more successful than conventional standard therapy or a waiting list control group.3

Considering these findings, the results obtained in the review by Jung et al. suggest that acupuncture may remain a therapeutic opportunity in patients suffering from temporomandibular pain. The clinically most relevant question is obviously not whether acupuncture works better than sham acupuncture, but how acupuncture behaves as compared to standard care or no therapy. Therefore, RCTs with larger sample sizes and longer observation periods are needed to gain deeper knowledge about the efficacy and/or effectiveness of acupuncture for TMD patients. Readers of this journal are well aware of the fact that these methodological shortcomings are by no means limited to the topic covered in Jung et al.'s review.

References

La Touche R, Goddard G, De-la-Hoz JL, et al. Acupuncture in the treatment of pain in temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin J Pain 2010; 26: 541–550.

Cho SH, Whang WW . Acupuncture for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review. J Orofac Pain 2010; 24: 152–162.

Witt CM, Brinkhaus B, Willich SN . Acupuncture. Clinical studies on efficacy and effectiveness in patients with chronic pain. Bundesgesundheitsblatt – Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 2006; 49: 736–742.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Address for correspondence: BC. Shin, Division of Clinical Medicine, School of Korean Medicine, Pusan National University, Yangsan 626-870, Kyungnam, South Korea. E-mail: drshinbc@gmail.com or drshinbc@pusan.ac.kr

Jung A, Shin BC, Lee MS, Sim H, Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating temporomandibular joint disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, sham-controlled trials. J Dent 2011; 39: 341–350.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Türp, J. Limited evidence that acupuncture is effective for treating temporomandibular disorders. Evid Based Dent 12, 89 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400816

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ebd.6400816