Abstract

We investigated whether tobacco use causes cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) in a large cohort study with complete and long-term follow-up. A total of 756 incident cases occurred in a cohort of 337 311 men during a 30-year follow-up period, but no association was found between any kind of smoking tobacco use and CSCC risk, nor any risk change with increasing dose, duration or time since smoking cessation. Snuff use was associated with a decreased risk of CSCC. Overall, our study provides no evidence that tobacco use increases the risk of CSCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (CSCC) is a relatively common cancer worldwide, more common in males and the elderly, and a four-fold increase in age-standardised incidence has occurred in Sweden over the last four decades and this trend seems to be continuing (Cancer Incidence in Sweden, 2003). Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is recognised as the most important risk factor for CSCC (Armstrong and Kricker, 2001), although other definite or possible risk factors include immunosuppression (London et al, 1995), infection with oncogenic viruses (Harwood et al, 2000), chronic inflammatory skin diseases (Boffetta et al, 2001), exposure to arsenic and high body mass index (BMI) (Chen et al 2003).

Tobacco smoke and oral snuff contain a large number of carcinogenic substances (Wiencke, 2002; IARC, 2004). However, the relationship between tobacco use and/or oral snuff and CSCC has not been sufficiently investigated among humans and the evidence has been somewhat conflicting (Grodstein et al, 1995; Nilsson, 1998; Ramsay et al, 2000; de Hertog et al, 2001; Chen et al, 2003; Lindelöf et al, 2003; Struijk et al, 2003; IARC, 2004).

We have investigated the possible role of tobacco smoking, snuff dipping and BMI in CSCC aetiology in a large nationwide cohort of Swedish construction workers.

Subjects and methods

The cohort and follow-up

The Construction Industry's Organization for Working Environment, Safety and Health (Bygghälsan) provided outpatient health services to construction workers all over Sweden from 1969 through 1993. Beginning in 1971, the information collected was stored in a computerised register, as described elsewhere (Nyrén et al, 1996). The first visit to the clinic defined entry into the cohort. Since no information on smoking history was collected from 1975 to 1977, we only included the workers who were registered between 1971–1975 and 1978–1992. Since over 95% of the cohort were men, we restricted our study to male workers and overall, 337 311 men were included in the subsequent analyses. Exposure information was obtained by self-administered questionnaires double-checked by a nurse. The quality of the tobacco data has been reviewed and the answers are believed to be of high validity.

Each cohort member was followed from date of entry into the cohort until CSCC diagnosis, death, emigration or end of follow-up 31 December 2000, whichever occurred first. The unique Swedish 10-digit personal identification number was used for follow-up by record linkage to the nationwide National Death Registry (date and cause of death), the Migration Registry (date of emigration) and the Swedish Cancer Registry (Cancer Incidence in Sweden, 2003).

Statistical analyses

The distribution of BMI was analysed in four groups according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria: underweight ⩽18.5; normal weight 18.6–25; overweight 25–30 and obese >30. Age was categorised in 5-year intervals. Cigarettes were assumed to contain 1 g of tobacco and cigars 6 g of tobacco each. Age-adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using proportional hazards Cox regression model, with age and the relevant exposure factors as independent variables (Stata Statistical Software: Release 8.2. College Station, TX, USA: Stata Corporation). Interaction effects between tobacco variables, age and BMI were also included in the model and likelihood ratio tests were used to assess their significance.

Results

Throughout follow-up, a total of 756 men developed CSCC, the risk increasing substantially with age. The mean age at entry was 34.2 (range 14–82) years and cohort members were followed on average for 19.4 years (range 0–31.3), yielding a total of 6 536 910 person-years of follow-up. In total, 58% of the subjects had ever smoked some tobacco product and 28% were ever snuff dippers. About 43% used one tobacco product only (29% were pure cigarette smokers and 13% were pure snuff dippers) and approximately 21% mixed two or more tobacco products – most frequently cigarettes and pipe (5%) or cigarettes and snuff (12%).

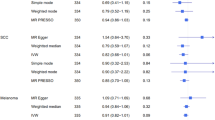

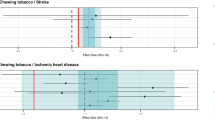

Table 1 summarises the IRR and corresponding CI for all smoking tobacco taken together. Overall, no association between tobacco and the development of CSCC was found. Former and current smokers showed an IRR of 0.95 (95% CI 0.77–1.18) and 0.97 (95% CI 0.80–1.17), respectively, compared to those who never smoked. No effect could be detected with increasing dose, duration or time since cessation.

Table 2 displays the IRR and CI for the tobacco products separately and the association with BMI. Again, we found no effect of any of the different smoking tobacco products on the risk of developing CSCC. Pure cigarette smokers had an IRR of 1.04 (95% CI 0.85–1.26), pure cigar smokers 0.88 (95% CI 0.45–1.71) and pure pipe smokers 0.81 (95% CI 0.62–1.05) compared to nontobacco users. No dose–response trends were revealed.

Snuff use was found to be negatively associated with the risk of developing CSCC (IRR 0.64; 95% CI 0.44–0.95). This effect was even stronger among those who had used snuff for more than 30 years. Subjects categorised as underweight, overweight or obese were not at an increased risk of CSCC compared to those of normal weight.

Discussion

Our main finding is that the use of tobacco smoking is not associated with an increased risk of CSCC, although we found a negative association between oral moist snuff and CSCC risk. The potential impact of occupational sunlight exposure on CSCC in this cohort has been evaluated previously and no association was found (Håkansson et al, 2001), perhaps because outdoor workers wear protective clothing while working. Unfortunately, we do not have information on recreational sun habits among the cohort members.

Previous investigations have reported relative risks of 1.5–4.1 between cigarette smoking and CSCC (Aubry and MacGibbon, 1985; Grodstein et al, 1995; Ramsay et al, 2000; De Hertog et al, 2001; Struijk et al, 2003), whereas others found no such association (Chen et al, 2003; Lindelöf et al, 2003). In general, most studies have been case–control in design, focused only on cigarette smoking and used rather crude exposure measures; previous cohort studies were unable to study skin cancer since they mainly used mortality instead of incidence data.

In the few studies of pipe and cigar smoking and BMI as risk factors of CSCC (De Hertog et al, 2001; Efird et al, 2002; Chen et al, 2003), pipe smoking and underweight have been associated with elevated risk of CSCC in contrast to our results. No studies have specifically addressed the impact of snuff use on CSCC.

The major strengths of this study of Swedish construction workers are its large size, the prospective collection of exposure details and almost complete follow-up. Any residual misclassification would presumably be nondifferential and would not have any major impact on the findings.

Change history

16 November 2011

This paper was modified 12 months after initial publication to switch to Creative Commons licence terms, as noted at publication

References

Armstrong B, Kricker A (2001) The epidemiology of UV induced skin cancer. J Photochem Photobiol B 63 (1–3): 8–18, Review.

Aubry F, MacGibbon B (1985) Risk factors of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: a case control study in the Montreal region. Cancer 55: 907–911

Boffetta P, Gridley G, Lindelöf B (2001) Cancer risk in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized for psoriasis in Sweden. J Invest Dermatol 117: 1531–1537

Chen Y-C, Guo Y-L, Su H-J, Hsueh Y-M, Smith T, Ryan L, Lee M-S, Chao S-C, Lee JY-Y, Christiani DC (2003) Arsenic methylation and skin cancer risk in southwestern Taiwan. J Occup Environ Med 45: 241–248

De Hertog S, Wensveen C, Bastiaens M, Kielich C, Berkhout M, Westendorp R, Vermeer B, Bouves Bavinck J (2001) Relation between smoking and skin cancer. J Clin Oncol 19: 231–238

Efird J, Friedman G, Habel L, Tekawa I, Nelson L (2002) Risk of subsequent cancer following invasive or in situ squamous cell skin cancer. Ann Epidemiol 12: 469–475

Grodstein F, Speizer F, Hunter D (1995) A prospective Study of incident squamous cell carcinoma of the skin in the nurses health study. J Natl Cancer Inst 87: 1061–1066

Harwood C, Suertheran T, McGregor J, Spink P, Leigh I Breuer J, Proby C (2000) Human papillomavirus infection and non-melanoma skin cancer in immunosuppressed and immunocompetent individuals. J Med Virol 61: 289–297

Håkansson N, Floderus B, Feychting M, Hallin N (2001) Occupational sunlight exposure and cancer incidence among Swedish construction workers. Epidemiology 12: 552–557

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (2004) Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum 83: 1–1438

Lindelöf B, Granath F, Dal H, Brandberg Y, Adami J, Ullen H (2003) Sun habits in kidney transplant recipients with skin cancer: a case–control study of possible causative factors. Acta Derm Venerol 83: 189–193

London NJ, Farmery SM, Will EJ, Davison AM, Lodge JPA (1995) Risk of neoplasia in renal transplant patients. Lancet 346: 403–406

Nilsson R (1998) A qualitative and quantitative risk assessment of snuff dipping. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 28 (1): 1–16

Nyrén O, Bergström R, Nyström L, Engholm G, Ekbom A, Adami H-O, Knutsson A, Stjernberg N (1996) Smoking and colorectal cancer: a 20-year follow-up study of Swedish construction workers. J Natl Cancer Inst 88: 1302–1307

Ramsay H, Fryer A, Reece S, Smith A, Harden P (2000) Clinical risk factors associated with nonmelanoma skin cancer in renal transplant recipients. Am J kidney Dis 36 (1): 167–176

Struijk L, Bouwes Bavinck J, Wanningen P, MEijden E, Westendorp R, Schegget J (2003) Presence of human papillomavirus DNA in plucked eyebrow hairs is associated with a history of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol 121 (6): 1531–1535

The Swedish Cancer Registry. Cancer incidence in Sweden, 2003. Stockholm: National Board of Health welfare, 2003 http://www.sos.se/FULLTEXT/42/2002-42-5/2002-42-5.pdf

Wiencke J (2002) DNA adduct burden and tobacco carcinogenesis (review). Oncogene 21: 7376–7391

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by a grant from the Swedish Cancer Society.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

From twelve months after its original publication, this work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Odenbro, Å., Bellocco, R., Boffetta, P. et al. Tobacco smoking, snuff dipping and the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Br J Cancer 92, 1326–1328 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602475

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6602475

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Lifestyle behaviors and sun exposure among individuals diagnosed with skin cancer: a cross-sectional analysis of 2018 BRFSS data

Journal of Cancer Survivorship (2021)

-

The association between smoking and risk of skin cancer: a meta-analysis of cohort studies

Cancer Causes & Control (2020)

-

Heterogeneous relationships of squamous and basal cell carcinomas of the skin with smoking: the UK Million Women Study and meta-analysis of prospective studies

British Journal of Cancer (2018)

-

Predictors of Squamous Cell Carcinoma in High-Risk Patients in the VATTC Trial

Journal of Investigative Dermatology (2013)

-

Case–control study of smoking and non-melanoma skin cancer

Cancer Causes & Control (2012)