Abstract

The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System is both a conceptual and practical advance over its 2007 predecessor. For the first time, the WHO classification of CNS tumors uses molecular parameters in addition to histology to define many tumor entities, thus formulating a concept for how CNS tumor diagnoses should be structured in the molecular era. As such, the 2016 CNS WHO presents major restructuring of the diffuse gliomas, medulloblastomas and other embryonal tumors, and incorporates new entities that are defined by both histology and molecular features, including glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype and glioblastoma, IDH-mutant; diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M–mutant; RELA fusion–positive ependymoma; medulloblastoma, WNT-activated and medulloblastoma, SHH-activated; and embryonal tumour with multilayered rosettes, C19MC-altered. The 2016 edition has added newly recognized neoplasms, and has deleted some entities, variants and patterns that no longer have diagnostic and/or biological relevance. Other notable changes include the addition of brain invasion as a criterion for atypical meningioma and the introduction of a soft tissue-type grading system for the now combined entity of solitary fibrous tumor / hemangiopericytoma—a departure from the manner by which other CNS tumors are graded. Overall, it is hoped that the 2016 CNS WHO will facilitate clinical, experimental and epidemiological studies that will lead to improvements in the lives of patients with brain tumors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

For the past century, the classification of brain tumors has been based largely on concepts of histogenesis that tumors can be classified according to their microscopic similarities with different putative cells of origin and their presumed levels of differentiation. The characterization of such histological similarities has been primarily dependent on light microscopic features in hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections, immunohistochemical expression of lineage-associated proteins and ultrastructural characterization. For example, the 2007 World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System (2007 CNS WHO) grouped all tumors with an astrocytic phenotype separately from those with an oligodendroglial phenotype, no matter if the various astrocytic tumors were clinically similar or disparate [26].

Studies over the past two decades have clarified the genetic basis of tumorigenesis in the common and some rarer brain tumor entities, raising the possibility that such an understanding may contribute to classification of these tumors [25]. Some of these canonical genetic alterations were known as of the 2007 CNS WHO, but at that time it was not felt that such changes could yet be used to define specific entities; rather, they provided prognostic or predictive data within diagnostic categories established by conventional histology. In 2014, a meeting held in Haarlem, the Netherlands, under the auspices of the International Society of Neuropathology, established guidelines for how to incorporate molecular findings into brain tumor diagnoses, setting the stage for a major revision of the 2007 CNS WHO classification [28]. The current update (2016 CNS WHO) thus breaks with the century-old principle of diagnosis based entirely on microscopy by incorporating molecular parameters into the classification of CNS tumor entities [27]. To do so required an international collaboration of 117 contributors from 20 countries and deliberations on the most controversial issues at a three-day consensus conference by a Working Group of 35 neuropathologists, neuro-oncological clinical advisors and scientists from 10 countries. The present review summarizes the major changes between the 2007 and 2016 CNS WHO classifications.

Classification

The 2016 CNS WHO is summarized in Table 1 and officially represents an update of the 2007 4th Edition rather than a formal 5th Edition. At this point, a decision to undertake the 5th Edition series of WHO Blue Books has not been made, but given the considerable progress in the fields, both the Hematopoietic/Lymphoid and CNS tumor volumes were granted permission for 4th Edition updates. The 2016 update contains numerous differences from the 2007 CNS WHO [26]. The major approaches and changes are summarized in Table 2 and described in more detail in the following sections. A synopsis of tumor grades for selected entities is given in Table 3.

General principles and challenges

The use of “integrated” [28] phenotypic and genotypic parameters for CNS tumor classification adds a level of objectivity that has been missing from some aspects of the diagnostic process in the past. It is hoped that this additional objectivity will yield more biologically homogeneous and narrowly defined diagnostic entities than in prior classifications, which in turn should lead to greater diagnostic accuracy as well as improved patient management and more accurate determinations of prognosis and treatment response. It will, however, also create potentially larger groups of tumors that do not fit into these more narrowly defined entities (e.g., the not otherwise specified/NOS designations, see below)—groups that themselves will be more amenable to subsequent study and improved classification.

A compelling example of this refinement relates to the diagnosis of oligoastrocytoma—a diagnostic category that has always been difficult to define and that suffered from high interobserver discordance [11, 47], with some centers diagnosing these lesions frequently and others diagnosing them only rarely. Using both genotype (i.e., IDH mutation and 1p/19q codeletion status) and phenotype to diagnose these tumors results in nearly all of them being compatible with either an astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma [6, 44, 48], with only rare reports of molecularly “true” oligoastrocytomas consisting of histologically and genetically distinct astrocytic (IDH-mutant, ATRX-mutant, 1p/19q-intact) and oligodendroglial (IDH-mutant, ATRX-wildtype and 1p/19q-codeleted) tumor populations [14, 49]. As a result, both the more common astrocytoma and oligodendroglioma subtypes become more homogeneously defined. In the 2016 CNS WHO, therefore, the prior diagnoses of oligoastrocytoma and anaplastic oligoastrocytoma are now designated as NOS categories, since these diagnoses should be rendered only in the absence of diagnostic molecular testing or in the very rare instance of a dual genotype oligoastrocytoma.

The diagnostic use of both histology and molecular genetic features also raises the possibility of discordant results, e.g., a diffuse glioma that histologically appears astrocytic but proves to have IDH mutation and 1p/19q codeletion, or a tumor that resembles oligodendroglioma by light microscopy but has IDH, ATRX and TP53 mutations in the setting of intact 1p and 19q. Notably, in each of these situations, the genotype trumps the histological phenotype, necessitating a diagnosis of oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q-codeleted in the first instance and diffuse astrocytoma, IDH-mutant in the second.

The latter example of classifying astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas and oligoastrocytomas leads to the question of whether classification can proceed on the basis of genotype alone, i.e., without histology. At this point in time, this is not possible: one must still make a diagnosis of diffuse glioma (rather than some other tumor type) to understand the nosological and clinical significance of specific genetic changes. In addition, WHO grade determinations are still made on the basis of histologic criteria. Another reason why phenotype remains essential is that, as mentioned above, there are individual tumors that do not meet the more narrowly defined phenotype and genotype criteria, e.g., the rare phenotypically classical diffuse astrocytoma that lacks the signature genetic characteristics of IDH and ATRX mutations. Nevertheless, it remains possible that future WHO classifications of the diffuse gliomas, in the setting of deeper and broader genomic capabilities, will require less histological evaluation—perhaps only a diagnosis of “diffuse glioma.” For now, the 2016 CNS WHO is predicated on the basis of combined phenotypic and genotypic classification, and on the generation of “integrated” diagnoses [28].

Lastly, it is important to acknowledge that changing the classification to include some diagnostic categories that require genotyping may create challenges with respect to testing and reporting, which have been discussed in detail elsewhere [28]. These challenges include: the availability and choice of genotyping or surrogate genotyping assays; the approaches that may need to be taken by centers without access to molecular techniques or surrogate immunostains; and the actual formats used to report such “integrated” diagnoses [28]. Nonetheless, the implementation of combined phenotypic–genotypic diagnostics in some large centers and the growing availability of immunohistochemical surrogates for molecular genetic alterations suggest that most of these challenges will be overcome readily in the near future [9, 40].

Nomenclature

Combining histopathological and molecular features into diagnoses necessarily results in portmanteau diagnostic terms and raises the need to standardize such terminology in as practical a manner as possible. In general, the 2016 CNS WHO decision was to approximate the naming conventions of the hematopoietic/lymphoid pathology community, which has incorporated molecular information into diagnoses in the past. As detailed below, CNS tumor diagnoses should consist of a histopathological name followed by the genetic features, with the genetic features following a comma and as adjectives, as in: Diffuse astrocytoma, IDH-mutant and Medulloblastoma, WNT-activated.

For those entities with more than one genetic determinant, the multiple necessary molecular features are included in the name: Oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q-codeleted.

For a tumor lacking a genetic mutation, the term wildtype can be used if an official “wildtype” entity exists: Glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype. However, it should be pointed out that in most such situations, a formal wildtype diagnosis is not available, and a tumor lacking a diagnostic mutation is given an NOS designation (see below).

For tumor entities in which a specific genetic alteration is present or absent, the terms “positive” can be used if the molecular characteristic is present: Ependymoma, RELA fusion–positive.

For sites lacking any access to molecular diagnostic testing, a diagnostic designation of NOS (i.e., not otherwise specified) is permissible for some tumor types. These have been added into the classification in those places where such diagnoses are possible. An NOS designation implies that there is insufficient information to assign a more specific code. In this context, NOS in most instances refers to tumors that have not been fully tested for the relevant genetic parameter(s), but in rare instances may also include tumors that have been tested but do not show the diagnostic genetic alterations. In other words, NOS does not define a specific entity; rather it designates a group of lesions that cannot be classified into any of the more narrowly defined groups. An NOS designation thus represents those cases about which we do not know enough pathologically, genetically and clinically and which should, therefore, be subject to future study before additional refinements in classification can be made.

With regard to formatting, italics are used for specific gene symbols (e.g., ATRX) but not for gene families (e.g., IDH, H3). To avoid numerous sequential hyphens, wildtype has been used without a hyphen and en-dashes have been used in certain designations (e.g., RELA fusion–positive). Finally, as in the past, WHO grades are written in Roman numerals (e.g., I, II, III and IV; not 1, 2, 3 and 4).

Definitions, disease summaries and commentaries

Entities within the 2016 classification begin with a Definition section that itself starts with an italicized definitional first clause that describes the necessary (i.e., entity-defining) diagnostic criteria. This is followed by characteristic associated findings. For example, the definition of oligodendroglioma, IDH-mutant and 1p/19q-codeleted includes a first sentence: “A diffusely infiltrating, slow-growing glioma with IDH1 or IDH2 mutation and codeletion of chromosomal arms 1p and 19q” (which is the italicized, entity-defining criteria), followed by sentences such as “Microcalcifications and a delicate branching capillary network are typical” (findings that are highly characteristic of the entity, but not necessary for the diagnosis). The diagnostic criteria and characteristic features are then followed by the remainder of the disease summary, in which other notable clinical, pathological and molecular findings are given. Finally, for some tumors, there is a commentary that provides information on classification, clarifying the nature of the genetic parameters to be evaluated and providing genotyping information for distinguishing overlapping histological entities. Notably, the classification does not mandate specific testing techniques, leaving that decision up to the individual practitioner and institution. Nonetheless, the commentary sections clarify certain genetic interpretations, e.g., in what situations IDH status can be designated as wildtype (depending on tumor type and, in some instances, patient age) and what constitutes prognostically favorable 1p/19q codeletion (combined whole-arm losses, which in IDH-mutant and histologically classic tumors can be assumed even when only single loci on each arm have been tested by fluorescence in situ hybridization).

Newly recognized entities, variants and patterns

A number of newly recognized entities, variants and patterns have been added. Variants are subtypes of accepted entities that are sufficiently well characterized pathologically to achieve a place in the classification and have potential clinical utility. Patterns are histological features that are readily recognizable but usually do not have clear clinicopathological significance. These newly recognized entities, variants and patterns are listed in Table 2 and discussed briefly in their respective sections below.

Diffuse gliomas

The nosological shift to a classification based on both phenotype and genotype expresses itself in a number of ways in the classification of the diffuse gliomas (Fig. 1). Most notably, while in the past all astrocytic tumors had been grouped together, now all diffusely infiltrating gliomas (whether astrocytic or oligodendroglial) are grouped together: based not only on their growth pattern and behaviors, but also more pointedly on the shared genetic driver mutations in the IDH1 and IDH2 genes. From a pathogenetic point of view, this provides a dynamic classification that is based on both phenotype and genotype; from a prognostic point of view, it groups tumors that share similar prognostic markers; and from the patient management point of view, it guides the use of therapies (conventional or targeted) for biologically and genetically similar entities.

A simplified algorithm for classification of the diffuse gliomas based on histological and genetic features (see text and 2016 CNS WHO for details). A caveat to this diagram is that the diagnostic “flow” does not necessarily always proceed from histology first to molecular genetic features next, since molecular signatures can sometimes outweigh histological characteristics in achieving an “integrated” diagnosis. A similar algorithm can be followed for anaplastic-level diffuse gliomas; * Characteristic but not required for diagnosis. Reprinted from [27], with permission from the WHO

In this new classification, the diffuse gliomas include the WHO grade II and grade III astrocytic tumors, the grade II and III oligodendrogliomas, the grade IV glioblastomas, as well as the related diffuse gliomas of childhood (see below). This approach leaves those astrocytomas that have a more circumscribed growth pattern, lack IDH gene family alterations and frequently have BRAF alterations (pilocytic astrocytoma, pleomorphic xanthastrocytoma) or TSC1/TSC2 mutations (subependymal giant cell astrocytoma) distinct from the diffuse gliomas. In other words, diffuse astrocytoma and oligodendrogliomas are now nosologically more similar than are diffuse astrocytoma and pilocytic astrocytoma; the family trees have been redrawn.

Diffuse astrocytoma and anaplastic astrocytoma

The WHO grade II diffuse astrocytomas and WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytomas are now each divided into IDH-mutant, IDH-wildtype and NOS categories. For both grade II and III tumors, the great majority falls into the IDH-mutant category if IDH testing is available. If immunohistochemistry for mutant R132H IDH1 protein and sequencing for IDH1 codon 132 and IDH2 codon 172 gene mutations are both negative, or if sequencing for IDH1 codon 132 and IDH2 codon 172 gene mutations alone is negative, then the lesion can be diagnosed as IDH-wildtype. It is important to recognize, however, that diffuse astrocytoma, IDH-wildtype is an uncommon diagnosis and that such cases need to be carefully evaluated to avoid misdiagnosis of lower grade lesions such as gangliogliomas; moreover, anaplastic astrocytoma, IDH-wildtype is also rare, and most such tumors will feature genetic findings highly characteristic of IDH-wildtype glioblastoma [6, 38]. Finally, in the setting of a diffuse astrocytoma or anaplastic astrocytoma, if IDH testing is not available or cannot be fully performed (e.g., negative immunohistochemistry without available sequencing), the resulting diagnosis would be diffuse astroctyoma, NOS, or anaplastic astrocytoma, NOS, respectively.

Historically, the prognostic differences between WHO grade II diffuse astrocytomas and WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytomas were highly significant [31]. Some recent studies, however, have suggested that the prognostic differences between IDH-mutant WHO grade II diffuse astrocytomas and IDH-mutant WHO grade III anaplastic astrocytomas are not as marked [32, 39]. Nonetheless, this has not been noted in all studies [20]. At this time, it is recommended that WHO grading is retained for both IDH-mutant and IDH-wildtype astrocytomas, although the prognosis of the IDH-mutant cases appears more favorable in both grades. Cautionary notes have been added to the 2016 classification in this regard.

Of note, two diffuse astrocytoma variants have been deleted from the WHO classification: protoplasmic astrocytoma, a diagnosis that was previously defined in only vague terms and is almost never made any longer given that tumors with this histological appearance are typically characterized as other more narrowly defined lesions; and fibrillary astrocytoma, since this diagnosis overlaps nearly entirely with the standard diffuse astrocytoma. As a result, only gemistocytic astrocytoma remains as a distinct variant of diffuse astrocytoma, IDH-mutant.

Gliomatosis cerebri has also been deleted from the 2016 CNS WHO classification as a distinct entity, rather being considered a growth pattern found in many gliomas, including IDH-mutant astrocytic and oligodendroglial tumors as well as IDH-wildtype glioblastomas [4, 13]. Thus, widespread brain invasion involving three or more cerebral lobes, frequent bilateral growth and regular extension to infratentorial structures is now mentioned as a special pattern of spread within the discussion of several diffuse glioma subtypes. Further studies are needed to clarify the biological basis for the unusually widespread infiltration in these tumors.

Glioblastomas

Glioblastomas are divided in the 2016 CNS WHO into (1) glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype (about 90 % of cases), which corresponds most frequently with the clinically defined primary or de novo glioblastoma and predominates in patients over 55 years of age [30]; (2) glioblastoma, IDH-mutant (about 10 % of cases), which corresponds closely to so-called secondary glioblastoma with a history of prior lower grade diffuse glioma and preferentially arises in younger patients [30] (see Table 4); and (3) glioblastoma, NOS, a diagnosis that is reserved for those tumors for which full IDH evaluation cannot be performed. The definition of full IDH evaluation can differ for glioblastomas in older patients relative to glioblastomas in younger adults and relative to WHO grade II and grade III diffuse gliomas: in the latter situations, IDH sequencing is highly recommended following negative R132H IDH1 immunohistochemistry, whereas the near absence of non-R132H IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in glioblastomas from patients over about 55 years of age [7] suggests that sequencing may not be needed in the setting of negative R132H IDH1 immunohistochemistry in such patients.

One provisional new variant of glioblastoma has been added to the classification: epithelioid glioblastoma. It joins giant cell glioblastoma and gliosarcoma under the umbrella of IDH-wildtype glioblastoma. Epithelioid glioblastomas feature large epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular chromatin, and prominent nucleoli (often resembling melanoma cells), and variably present rhabdoid cells (Fig. 2). They have a predilection for children and younger adults, typically present as superficial cerebral or diencephalic masses, and often harbor a BRAF V600E mutation (which can be detected immunohistochemically) [5, 21, 22]. In one series, rhabdoid glioblastomas were distinguished from their similarly appearing epithelioid counterparts on the basis of loss of INI1 expression [23]. IDH-wildtype epithelioid glioblastomas often lack other molecular features of conventional adult IDH-wildtype glioblastomas, such as EGFR amplification and chromosome 10 losses; instead, there are frequent hemizygous deletions of ODZ3. Such cases may have an associated low-grade precursor, often but not invariably showing features of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma [1].

Epithelioid glioblastomas (Ep-GBM). Although the neuroimaging features are not specific, many cases show a superficial localization and sharp demarcation, as seen on this post-contrast T1-weighted MR image (a). Histologically, the Ep-GBM may also show a discrete border with adjacent brain, often suggestive of a metastasis (b). This mimicry is further complicated by the tumor cytology featuring large epithelioid cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, vesicular nuclei, and large melanoma-like nucleoli (c). Not uncommonly, a subset of tumor cells display eccentric nuclei and paranuclear inclusions that overlap with rhabdoid neoplasms (arrows). Some Ep-GBMs show features of a lower grade precursor in adjacent tissue; in this particular example, there was focal evidence of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, including bizarre giant cells despite lack of mitotic activity, numerous eosinophilic granular bodies, and xanthomatous appearing vacuolated astrocytes (d). GFAP expression is often limited (e) and may even be lacking entirely. In contrast, S100 protein is strongly expressed (f), whereas other melanoma markers are typically negative (not shown). Other glial markers, such as OLIG2 may also be positive (g), but many lack this protein as well. Roughly half of Ep-GBMs express BRAF V600E mutant protein as seen in this example (h)

Glioblastoma with primitive neuronal component was added as a pattern in glioblastoma. This pattern, previously referred to in the literature as glioblastoma with PNET-like component, is usually comprised of a diffuse astrocytoma of any grade (or oligodendroglioma in rare cases) that has well-demarcated nodules containing primitive cells that display neuronal differentiation (e.g., Homer Wright rosettes, gain of synaptophysin positivity and loss of GFAP expression) and that sometimes has MYC or MYCN amplification (Fig. 3); these tumors have a tendency for craniospinal fluid dissemination [34]. About a quarter develop in patients with a previously known lower grade glioma precursor, a subset of which shows R132H IDH1 immunoreactivity in both the glial and primitive neuronal components [17]. From a clinical point of view, the recognition of this pattern may prompt evaluation of the craniospinal axis to rule out tumor seeding.

Glioblastomas with primitive neuronal components (GBM-PNC; b and e–g show the astrocytic component on the left and the primitive neuronal component on the right). In this GBM-PNC, the imaging was essentially identical to that of conventional GBM, including a rim-enhancing mass; however, the markedly restricted diffusion on this DWI MR image highlights the more cellular primitive component (a). The primitive clone in this GBM-PNC is evident as a highly cellular nodule within an otherwise classic diffuse astrocytoma (b). Well-formed Homer Wright rosettes were seen in the primitive portion of this GBM-PNC (c). Large cell/anaplastic features (similar to those of medulloblastoma) are seen in a subset of GBM-PNC; note the increased cell size, vesicular chromatin, macronucleoli, and cell–cell wrapping (arrows) in this case (d). The primitive component typically displays loss of glial marker expression, including GFAP (not shown) and OLIG2 (e), along with gain of neuronal features, such as synaptophysin positivity (f; note also staining of Homer Wright rosettes). A subset of cases demonstrates features of secondary glioblastoma, including IDH1 R132H mutant protein expression (g). FISH revealed MYCN gene amplification limited to the primitive foci of this GBM-PNC (h; centromere 2 signals in red and MYCN signals in green)

Small cell glioblastoma/astrocytoma and granular cell glioblastoma/astrocytoma remain patterns, the former characterized by uniform, deceptively bland small neoplastic cells often resembling oligodendroglioma and frequently demonstrating EGFR amplification, and the latter by markedly granular to macrophage-like, lysosome-rich tumor cells. In both examples, there is a particularly poor glioblastoma-like prognosis even in the absence of microvascular proliferation or necrosis.

Oligodendrogliomas

The diagnosis of oligodendroglioma and anaplastic oligodendroglioma requires the demonstration of both an IDH gene family mutation and combined whole-arm losses of 1p and 19q (1p/19q codeletion). In the absence of positive mutant R132H IDH1 immunohistochemistry, sequencing of IDH1 codon 132 and IDH2 codon 172 is recommended. In the absence of testing capabilities or in the setting of inconclusive genetic results, a histologically typical oligodendroglioma should be diagnosed as NOS. In the setting of an anaplastic oligodendroglioma with non-diagnostic genetic results, careful evaluation for genetic features of glioblastoma may be undertaken [6]. It is also recognized that tumors of childhood that histologically resemble oligodendroglioma often do not demonstrate IDH gene family mutation and 1p/19q codeletion; until such tumors are better understood at a molecular level, they should be included in the oligodendroglioma, NOS category. However, care should be taken to exclude histological mimics like pilocytic astrocytoma, dysembryoplastic neuroepithelial tumor and clear cell ependymoma.

Oligoastrocytomas

In the 2016 CNS WHO, the diagnosis of oligoastrocytoma is strongly discouraged. Nearly all tumors with histological features suggesting both an astrocytic and an oligodendroglial component can be classified as either astrocytoma or oligodendroglioma using genetic testing [44, 48]. The diagnoses of WHO grade II oligoastrocytoma and WHO grade III anaplastic oligoastrocytoma are, therefore, assigned NOS designations, indicating that they can only be made in the absence of appropriate diagnostic molecular testing. Notably, rare cases of “true” oligoastrocytomas have been reported in the literature, with phenotypic and genotypic evidence of spatially distinct oligodendroglioma and astrocytoma components in the same tumor [14, 49]; until further reports confirming such tumors are available for evaluation as part of the next WHO classification, they should be included under the provisional entities of oligoastrocytoma, NOS, or anaplastic oligoastrocytoma, NOS. In addition, in such settings, particular care should be taken to avoid misinterpretation of regional heterogeneity due to technical problems with ancillary techniques, such as false-negative ATRX immunostaining or false-positive FISH results for 1p/19q codeletion, which can occur regionally within tissue specimens.

Pediatric diffuse gliomas

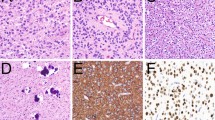

In the past, pediatric diffuse gliomas were grouped with their adult counterparts, despite known differences in behavior between pediatric and adult gliomas with similar histological appearances. Information on the distinct underlying genetic abnormalities in pediatric diffuse gliomas is beginning to allow the separation of some entities from histologically similar adult counterparts [24, 37, 52]. One narrowly defined group of tumors primarily occurring in children (but sometimes in adults too) is characterized by K27M mutations in the histone H3 gene H3F3A, or less commonly in the related HIST1H3B gene, a diffuse growth pattern, and a midline location (e.g., thalamus, brain stem, and spinal cord) (Fig. 4) [19, 51]. This newly defined entity is termed diffuse midline glioma, H3 K27M–mutant and includes tumors previously referred to as diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG). The identification of this phenotypically and molecularly defined set of tumors provides a rationale for therapies directed against the effects of these mutations.

Diffuse midline gliomas, H3 K27M–mutant. These tumors most often involve the brain stem (especially pons), spinal cord (a–d), and thalamus (e–f) in children and young adults. The morphologic spectrum varies widely, as in these two examples. This spinal lesion presented as a non-enhancing intramedullary mass with expansion and signal abnormalities on T2-weighted MRI (a). There was only minimal hypercellularity and cytologic atypia (b), but tumor cells strongly expressed the H3 K27–mutant protein (c) and also showed loss of ATRX expression (d). In contrast, the thalamic example showed a rim-enhancing mass on post-contrast T1 MRI (e) and histology demonstrated classic features of glioblastoma with prominent multinucleated giant cells (f). In addition to H3 K27M–mutant protein expression (g), there was strong p53 staining (h)

Other astrocytomas

Anaplastic pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma, WHO grade III, has been added to the 2016 CNS WHO as a distinct entity, as opposed to the descriptive title of pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma with anaplastic features in the past. Grading of a pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma as anaplastic requires 5 or more mitoses per 10 high-power fields; necrosis may be present, but the significance of necrosis in the absence of elevated mitotic activity is unclear [16]. Patients with such tumors have shorter survival times when compared to those with WHO grade II pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas.

The grading of pilomyxoid astrocytoma has also been changed. While previously designated as WHO grade II, recent studies have shown extensive histological and genetic overlap between pilomyxoid and pilocytic astrocytomas, with some of the former maturing into the latter over time and less certainty that the pilomyxoid variant always follows a more aggressive course than a more classic appearing suprasellar pilocytic astrocytoma. For these reasons, it is not clear that pilomyxoid astrocytoma should automatically be assigned to WHO grade II and the suggestion was made to suppress grading of pilomyxoid astrocytomas until further studies clarify their behavior.

Ependymomas

While it was recognized that the grading of ependymomas according to existing WHO criteria is difficult to apply and of questionable clinical utility [10], a more prognostic and reproducible classification and grading scheme is yet to be published. As a result, the difficulty in assigning clinical significance to ependymoma histological grades is discussed in the grading sections of both the Ependymoma and Anaplastic Ependymoma chapters. Nonetheless, it is expected that continuing studies of the molecular characteristics of ependymoma will provide more precise and objective means of subdividing these tumors, allowing for more narrowly defined tumor groups. In the meanwhile, one genetically defined ependymoma subtype has been accepted: Ependymoma, RELA fusion–positive [33, 36]. This variant accounts for the majority of supratentorial tumors in children. The specificity of L1CAM expression, a potential immunohistochemical surrogate for this variant [33], has yet to be fully elucidated. Lastly, one ependymoma variant, cellular ependymoma, has been deleted from the classification, since it was considered to overlap extensively with standard ependymoma.

Neuronal and mixed neuronal-glial tumours

The newly recognized entity diffuse leptomeningeal glioneuronal tumor is an entity known in the literature under a variety of similar terms, perhaps most notably as disseminated oligodendroglial-like leptomeningeal tumor of childhood [42]. These tumors present with diffuse leptomeningeal disease, with or without a recognizable parenchymal component (commonly in the spinal cord), most often in children and adolescents, and histologically demonstrate a monomorphic clear cell glial morphology, reminiscent of oligodendroglioma (Fig. 5), although often with expression of synaptophysin in addition to OLIG2 and S-100 [42]. An additional neuronal component can be detected in a subset of cases. The lesions commonly harbor BRAF fusions as well as deletions of chromosome arm 1p, either alone or occasionally combined with 19q [43]. However, IDH mutations are absent. Nonetheless, the nosological position of these tumors remains somewhat unclear at the present time, with some pathological and genetic features suggesting a relationship to pilocytic astrocytoma or to glioneuronal tumors. The prognosis is variable, with tumors showing relatively slow growth but considerable morbidity from secondary hydrocephalus.

Diffuse leptomeningeal glioneuronal tumors (DLGNT). At autopsy, this DLGNT patient had widespread expansion and fibrosis of spinal (a) and cerebral (b) subarachnoid spaces, along with intraventricular masses and variably cystic, mucoid intraparenchymal extensions along perivascular Virchow-Robin spaces (gross photos courtesy of Dr. William McDonald, Minneapolis, MN, USA). The DLGNT biopsy specimen showed a leptomeningeal infiltrate (d) with oligodendroglioma-like cytologic features (d). DLGNT cells are OLIG2-positive (e), along with variable synaptophysin immunoreactivity (f). Common genetic alterations detected by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) include chromosome 1p deletion (g; tumor cells showing roughly half as many red 1p as green 1q signals) and BRAF fusion/duplication (h; increased red BRAF and green KIAA1549 copy numbers, in addition to yellow fusion signals)

A newly recognized architectural appearance is the multinodular and vacuolated pattern that may be related to ganglion cell tumors. Reported as multinodular and vacuolated tumor of the cerebrum [15], these are low-grade lesions that may even be malformative in nature. They are comprised of multiple nodules of tumor with a conspicuous vacuolation, and the tumor cells show glial and/or neuronal differentiation, including ganglion cells in some cases. Further characterization of these lesions is needed to understand its nosological place among CNS neoplasms.

Medulloblastomas

The classification of medulloblastomas produced the greatest conceptual challenges in devising a marriage of histological and molecular classification schemes. There are long-established histological variants of medulloblastoma that have clinical utility (e.g., desmoplastic/nodular, medulloblastoma with extensive nodularity, large cell, and anaplastic) and it is now widely accepted that there are four genetic (molecular) groups of medulloblastoma: WNT-activated, SHH-activated, and the numerically designated “group 3” and “group 4” [46]. Some of these histological and genetic variants are associated with dramatic prognostic and therapeutic differences. Rather than providing a long list of the many possible histological–molecular combinations, the classification lists “genetically defined” and “histologically defined” variants, with the expectation that a pathologist with the ability to undertake the molecular classification will generate an integrated diagnosis that includes both the molecular group and histological phenotype. In this regard, it was emphasized that there is a group of the most clinically relevant integrated diagnoses, which are given in Table 5.

This modular and integrated approach to diagnosis is novel, but likely represents a method that will become more common as knowledge of tumor genetics and phenotype–genotype correlation grows. It is also anticipated that such a modular approach will allow greater flexibility for future changes in classification as such knowledge expands.

Other embyronal tumors

The embryonal tumors other than medulloblastoma have also undergone substantial changes in their classification, with removal of the term primitive neuroectodermal tumor or PNET from the diagnostic lexicon. Much of the reclassification was driven by the recognition that many of these rare tumors display amplification of the C19MC region on chromosome 19 (19q13.42). C19MC-amplified tumors include the lesions previously known as ETANTR (embryonal tumors with abundant neuropil and true rosettes, but also referred to as embryonal tumors with multilayered rosettes), ependymoblastoma and, in some cases, medulloepithelioma [24]. In the 2016 CNS WHO, the presence of C19MC amplification results in a diagnosis of embryonal tumor with multilayered rosettes (ETMR), C19MC-altered. In the absence of C19MC amplification, a tumor with histological features conforming to ETANTR/ETMR should be diagnosed as embryonal tumor with multilayered rosettes, NOS, and a tumor with histological features of medulloepithelioma should be diagnosed as medulloepithelioma (recognizing that some apparently bona fide medulloepitheliomas do not have C19MC amplification).

Atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor (AT/RT) is now defined by alterations of either INI1 or, very rarely, BRG1 [2, 12, 18, 50]. These alterations can be evaluated using immunohistochemistry for the corresponding proteins, with loss of nuclear expression correlating with genetic alteration (in the setting of adequate control expression). If a tumor has histological features of AT/RT but does not harbor either of the diagnostic genetic alterations, only a descriptive diagnosis of CNS embryonal tumour with rhabdoid features is available; in other words, the diagnosis of AT/RT requires confirmation of the characteristic molecular defect.

The understanding of other embryonal tumors is undergoing changes, with an expectation that molecular markers could lead to more precise cataloging of these tumors and their subtypes. In the meanwhile, the 2016 CNS WHO has created a probable wastebasket category of CNS embryonal tumor, NOS that includes tumors previously designated as CNS PNET.

Nerve sheath tumors

The classification of cranial and paraspinal nerve sheath tumors is similar to that of the 2007 CNS WHO, although a few changes have been made. Given that melanotic schwannoma is both clinically (e.g., malignant behavior in a significant subset) and genetically (e.g., associations with Carney Complex and the PRKAR1A gene) distinct from conventional schwannoma, it is now classified as a distinct entity rather than as a variant. Hybrid nerve sheath tumors have been included in the 2016 CNS WHO because such tumors are increasingly being recognized in a variety of combinations; as such, this broad category was separated out as an entity, although it may well represent a group of tumors rather than one distinct subtype. Lastly, the 2016 CNS WHO now designates two subtypes of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST): epithelioid MPNST and MPNST with perineurial differentiation. These were considered sufficiently distinct clinically to warrant designation as variants, whereas other subtypes such as MPNST with divergent differentiation (malignant Triton tumor, glandular MPNST, etc.) simply represent histologic patterns.

Meningiomas

The classification and grading of meningiomas did not undergo revisions, save for the introduction of brain invasion as a criterion for the diagnosis of atypical meningioma, WHO grade II. While it has long been recognized that the presence of brain invasion in a WHO grade I meningioma confers recurrence and mortality rates similar to those of a WHO grade II meningioma in general [35], prior WHO classifications had considered invasion a staging feature rather than a grading feature and opted to discuss brain invasion as a separate heading. In the 2016 classification, brain invasion joins a mitotic count of 4 or more as a histological criterion that can alone suffice for diagnosing an atypical meningioma, WHO grade II. As in the past, atypical meningioma can also be diagnosed on the basis of the additive criteria of 3 of the other 5 histological features: spontaneous necrosis, sheeting (loss of whorling or fascicular architecture), prominent nucleoli, high cellularity and small cells (tumor clusters with high nuclear:cytoplasmic ratio).

Solitary fibrous tumor / hemangiopericytoma

Over the past decade, soft tissue pathologists have moved away from the designation hemangiopericytoma, diagnosing such tumors within the spectrum of solitary fibrous tumors, whereas neuropathologists have retained the term hemangiopericytoma given its historical understanding and distinct clinicopathologic correlations, such as high recurrence rates and long-term risk of systemic metastasis. Nonetheless, both solitary fibrous tumors and hemangiopericytomas, including those occurring in the neuraxis, share inversions at 12q13, fusing the NAB2 and STAT6 genes [8, 41], which leads to STAT6 nuclear expression that can be detected by immunohistochemistry [45]. It has thus become clear that solitary fibrous tumors and hemangiopericytomas are overlapping, if not identical entities. For this reason, the 2016 CNS WHO has created the combined term solitary fibrous tumor / hemangiopericytoma to describe such lesions. It is recognized that this term is cumbersome and it is likely that it will be shortened in the next WHO classification of CNS tumors.

The creation of a single designation for tumors in the spectrum of low-grade solitary fibrous tumor and the higher grade lesions previously designated as hemangiopericytoma and anaplastic hemangiopericytoma created a grading challenge relative to other CNS tumors. The WHO classifications of CNS tumors have always included grading as a malignancy scale, with a specific grade assigned to each entity rather than multiple grades within an entity (i.e., glioblastoma is grade IV, whereas a ductal carcinoma of the breast can be assigned a grade within the diagnosis of ductal carcinoma). To address this challenge in the context of solitary fibrous tumor / hemangiopericytoma, the 2016 CNS WHO has broken with the typical WHO CNS tradition and assigns three grades within the entity of solitary fibrous tumor / hemangiopericytoma: a grade I that corresponds most often to the highly collagenous, relatively low cellularity, spindle cell lesion previously diagnosed as solitary fibrous tumor; a grade II that corresponds typically to the more cellular, less collagenous tumor with plump cells and “staghorn” vasculature that was previously diagnosed in the CNS as hemangiopericytoma; and a grade III that most often corresponds to what was termed anaplastic hemangiopericytoma in the past, diagnosed on the basis of 5 or more mitoses per 10 high-power fields. Nonetheless, some tumors with a histological appearance more similar to traditional solitary fibrous tumor can also display malignant features and be assigned a WHO grade III, using the cutoff of 5 or more mitoses per 10 high-power fields. Additional studies will, therefore, be required to fine-tune this grading system [3]. Nonetheless, it is hoped that this break from how CNS tumors were usually graded in the past will allow for greater flexibility in grading CNS tumors in the future, which may be important as molecular characterization improves (see discussion of IDH-mutant diffuse astrocytic tumors, above).

Lymphomas and histiocytic tumours

Given the changes that have occurred in the classification of systemic lymphomas and histiocytic neoplasms over the past decade, the 2016 CNS WHO has expanded these categories to parallel those in the corresponding Hematopoietic/Lymphoid WHO classifications.

Summary

The 2016 CNS WHO represents a substantial step forward over its 2007 ancestor in that, for the first time, molecular parameters are used to establish brain tumor diagnoses. While this has introduced challenges in nomenclature, nosology and reporting structure, and while it is likely that the next CNS WHO classification will view the present one as an intermediate stage to the further incorporation of objective molecular data in classification, the 2016 CNS WHO sets the stage for such progress. It is hoped that these more objective and more precisely defined entities will allow for improved tailoring of patient therapy, better classification for clinical trials and experimental studies, and more precise categorization for epidemiological purposes. Moreover, while the classification has left some “wastebasket” categories, it allows for more focused study of these less defined groups that will eventually lead to clarification of their status. In addition, while the classification still enables diagnoses to be made in the absence of molecular data in many situations, those settings are clearly designated, allowing distinction of molecularly defined and non-molecularly defined groups. In the long run, we trust that the 2016 CNS WHO will facilitate the clinical, experimental and epidemiological studies that will lead to improvements in the lives of patients with brain tumors.

References

Alexandrescu S, Korshunov A, Lai SH, Dabiri S, Patil S, Li R, Shih CS, Bonnin JM, Baker JA, Du E et al (2015) Epithelioid glioblastomas and anaplastic epithelioid pleomorphic xanthoastrocytomas—same entity or first cousins? Brain Pathol. doi:10.1111/bpa.12295

Biegel JA (2006) Molecular genetics of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor. Neurosurg Focus 20:E11

Bouvier C, Metellus P, de Paula AM, Vasiljevic A, Jouvet A, Guyotat J, Mokhtari K, Varlet P, Dufour H, Figarella-Branger D (2012) Solitary fibrous tumors and hemangiopericytomas of the meninges: overlapping pathological features and common prognostic factors suggest the same spectrum of tumors. Brain Pathol 22:511–521. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2011.00552.x

Broniscer A, Chamdine O, Hwang S, Lin T, Pounds S, Onar-Thomas A, Shurtleff S, Allen S, Gajjar A, Northcott P et al (2016) Gliomatosis cerebri in children shares molecular characteristics with other pediatric gliomas. Acta Neuropathol 131:299–307. doi:10.1007/s00401-015-1532-y

Broniscer A, Tatevossian RG, Sabin ND, Klimo P Jr, Dalton J, Lee R, Gajjar A, Ellison DW (2014) Clinical, radiological, histological and molecular characteristics of paediatric epithelioid glioblastoma. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 40:327–336. doi:10.1111/nan.12093

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network, Brat DJ, Verhaak RG, Aldape KD, Yung WK, Salama SR, Cooper LA, Rheinbay E, Miller CR, Vitucci M et al (2015) Comprehensive, integrative genomic analysis of diffuse lower-grade gliomas. N Engl J Med 372:2481–2498. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1402121

Chen L, Voronovich Z, Clark K, Hands I, Mannas J, Walsh M, Nikiforova MN, Durbin EB, Weiss H, Horbinski C (2014) Predicting the likelihood of an isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 or 2 mutation in diagnoses of infiltrative glioma. Neurooncology 16:1478–1483. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nou097

Chmielecki J, Crago AM, Rosenberg M, O’Connor R, Walker SR, Ambrogio L, Auclair D, McKenna A, Heinrich MC, Frank DA et al (2013) Whole-exome sequencing identifies a recurrent NAB2-STAT6 fusion in solitary fibrous tumors. Nat Genet 45:131–132. doi:10.1038/ng.2522

Ellison DW, Dalton J, Kocak M, Nicholson SL, Fraga C, Neale G, Kenney AM, Brat DJ, Perry A, Yong WH et al (2011) Medulloblastoma: clinicopathological correlates of SHH, WNT, and non-SHH/WNT molecular subgroups. Acta Neuropathol 121:381–396. doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0800-8

Ellison DW, Kocak M, Figarella-Branger D, Felice G, Catherine G, Pietsch T, Frappaz D, Massimino M, Grill J, Boyett JM et al (2011) Histopathological grading of pediatric ependymoma: reproducibility and clinical relevance in European trial cohorts. J Negat Results Biomed 10:7. doi:10.1186/1477-5751-10-7

Giannini C, Scheithauer BW, Weaver AL, Burger PC, Kros JM, Mork S, Graeber MB, Bauserman S, Buckner JC, Burton J et al (2001) Oligodendrogliomas: reproducibility and prognostic value of histologic diagnosis and grading. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 60:248–262

Hasselblatt M, Gesk S, Oyen F, Rossi S, Viscardi E, Giangaspero F, Giannini C, Judkins AR, Fruhwald MC, Obser T et al (2011) Nonsense mutation and inactivation of SMARCA4 (BRG1) in an atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumor showing retained SMARCB1 (INI1) expression. Am J Surg Pathol 35:933–935. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182196a39

Herrlinger U, Jones DT, Glas M, Hattingen E, Gramatzki D, Stuplich M, Felsberg J, Bahr O, Gielen GH, Simon M et al (2015) Gliomatosis cerebri: no evidence for a separate brain tumor entity. Acta Neuropathol. doi:10.1007/s00401-015-1495-z

Huse JT, Diamond EL, Wang L, Rosenblum MK (2015) Mixed glioma with molecular features of composite oligodendroglioma and astrocytoma: a true “oligoastrocytoma”? Acta Neuropathol 129:151–153. doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1359-y

Huse JT, Edgar M, Halliday J, Mikolaenko I, Lavi E, Rosenblum MK (2013) Multinodular and vacuolating neuronal tumors of the cerebrum: 10 cases of a distinctive seizure-associated lesion. Brain Pathol 23:515–524. doi:10.1111/bpa.12035

Ida CM, Rodriguez FJ, Burger PC, Caron AA, Jenkins SM, Spears GM, Aranguren DL, Lachance DH, Giannini C (2014) Pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma: natural history and long-term follow-up. Brain Pathol. doi:10.1111/bpa.12217

Joseph NM, Phillips J, Dahiya S, M Felicella M, Tihan T, Brat DJ, Perry A (2013) Diagnostic implications of IDH1-R132H and OLIG2 expression patterns in rare and challenging glioblastoma variants. Mod Pathol. 26:315–326. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2012.173

Judkins AR (2007) Immunohistochemistry of INI1 expression: a new tool for old challenges in CNS and soft tissue pathology. Adv Anat Pathol 14:335–339. doi:10.1097/PAP.0b013e3180ca8b08

Khuong-Quang DA, Buczkowicz P, Rakopoulos P, Liu XY, Fontebasso AM, Bouffet E, Bartels U, Albrecht S, Schwartzentruber J, Letourneau L et al (2012) K27M mutation in histone H3.3 defines clinically and biologically distinct subgroups of pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas. Acta Neuropathol 124:439–447. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-0998-0

Killela PJ, Pirozzi CJ, Healy P, Reitman ZJ, Lipp E, Rasheed BA, Yang R, Diplas BH, Wang Z, Greer PK et al (2014) Mutations in IDH1, IDH2, and in the TERT promoter define clinically distinct subgroups of adult malignant gliomas. Oncotarget 5:1515–1525

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Aisner DL, Birks DK, Foreman NK (2013) Epithelioid GBMs show a high percentage of BRAF V600E mutation. Am J Surg Pathol 37:685–698. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e31827f9c5e

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Aisner DL, Foreman NK (2015) BRAF VE1 immunoreactivity patterns in epithelioid glioblastomas positive for BRAF V600E mutation. Am J Surg Pathol 39:528–540. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000000363

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Alassiri AH, Birks DK, Newell KL, Moore W, Lillehei KO (2010) Epithelioid versus rhabdoid glioblastomas are distinguished by monosomy 22 and immunohistochemical expression of INI-1 but not claudin 6. Am J Surg Pathol 34:341–354. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181ce107b

Korshunov A, Ryzhova M, Hovestadt V, Bender S, Sturm D, Capper D, Meyer J, Schrimpf D, Kool M, Northcott PA et al (2015) Integrated analysis of pediatric glioblastoma reveals a subset of biologically favorable tumors with associated molecular prognostic markers. Acta Neuropathol 129:669–678. doi:10.1007/s00401-015-1405-4

Louis DN (2012) The next step in brain tumor classification: “Let us now praise famous men”… or molecules? Acta Neuropathol 124:761–762. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-1067-4

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK (2007) World Health Organization histological classification of tumours of the central nervous system. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Louis DN, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Cavenee WK (2016) World Health Organization Histological Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. International Agency for Research on Cancer, France

Louis DN, Perry A, Burger P, Ellison DW, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Aldape K, Brat D, Collins VP, Eberhart C et al (2014) International Society Of Neuropathology-Haarlem consensus guidelines for nervous system tumor classification and grading. Brain Pathol 24:429–435. doi:10.1111/bpa.12171

Nonoguchi N, Ohta T, Oh JE, Kim YH, Kleihues P, Ohgaki H (2013) TERT promoter mutations in primary and secondary glioblastomas. Acta Neuropathol 126:931–937. doi:10.1007/s00401-013-1163-0

Ohgaki H, Kleihues P (2013) The definition of primary and secondary glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res 19:764–772. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3002

Ohgaki H, Kleihues P (2005) Population-based studies on incidence, survival rates, and genetic alterations in astrocytic and oligodendroglial gliomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 64:479–489

Olar A, Wani KM, Alfaro-Munoz KD, Heathcock LE, van Thuijl HF, Gilbert MR, Armstrong TS, Sulman EP, Cahill DP, Vera-Bolanos E et al (2015) IDH mutation status and role of WHO grade and mitotic index in overall survival in grade II–III diffuse gliomas. Acta Neuropathol 129:585–596. doi:10.1007/s00401-015-1398-z

Parker M, Mohankumar KM, Punchihewa C, Weinlich R, Dalton JD, Li Y, Lee R, Tatevossian RG, Phoenix TN, Thiruvenkatam R et al (2014) C11orf95-RELA fusions drive oncogenic NF-kappaB signalling in ependymoma. Nature 506:451–455. doi:10.1038/nature13109

Perry A, Miller CR, Gujrati M, Scheithauer BW, Zambrano SC, Jost SC, Raghavan R, Qian J, Cochran EJ, Huse JT et al (2009) Malignant gliomas with primitive neuroectodermal tumor-like components: a clinicopathologic and genetic study of 53 cases. Brain Pathol 19:81–90. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00167.x

Perry A, Stafford SL, Scheithauer BW, Suman VJ, Lohse CM (1997) Meningioma grading: an analysis of histologic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol 21:1455–1465

Pietsch T, Wohlers I, Goschzik T, Dreschmann V, Denkhaus D, Dorner E, Rahmann S, Klein-Hitpass L (2014) Supratentorial ependymomas of childhood carry C11orf95-RELA fusions leading to pathological activation of the NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Acta Neuropathol 127:609–611. doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1264-4

Ramkissoon LA, Horowitz PM, Craig JM, Ramkissoon SH, Rich BE, Schumacher SE, McKenna A, Lawrence MS, Bergthold G, Brastianos PK et al (2013) Genomic analysis of diffuse pediatric low-grade gliomas identifies recurrent oncogenic truncating rearrangements in the transcription factor MYBL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:8188–8193. doi:10.1073/pnas.1300252110

Reuss DE, Kratz A, Sahm F, Capper D, Schrimpf D, Koelsche C, Hovestadt V, Bewerunge-Hudler M, Jones DT, Schittenhelm J et al (2015) Adult IDH wild type astrocytomas biologically and clinically resolve into other tumor entities. Acta Neuropathol. doi:10.1007/s00401-015-1454-8

Reuss DE, Mamatjan Y, Schrimpf D, Capper D, Hovestadt V, Kratz A, Sahm F, Koelsche C, Korshunov A, Olar A et al (2015) IDH mutant diffuse and anaplastic astrocytomas have similar age at presentation and little difference in survival: a grading problem for WHO. Acta Neuropathol 129:867–873. doi:10.1007/s00401-015-1438-8

Reuss DE, Sahm F, Schrimpf D, Wiestler B, Capper D, Koelsche C, Schweizer L, Korshunov A, Jones DT, Hovestadt V et al (2015) ATRX and IDH1-R132H immunohistochemistry with subsequent copy number analysis and IDH sequencing as a basis for an “integrated” diagnostic approach for adult astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma and glioblastoma. Acta Neuropathol 129:133–146. doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1370-3

Robinson DR, Wu YM, Kalyana-Sundaram S, Cao X, Lonigro RJ, Sung YS, Chen CL, Zhang L, Wang R, Su F et al (2013) Identification of recurrent NAB2-STAT6 gene fusions in solitary fibrous tumor by integrative sequencing. Nat Genet 45:180–185. doi:10.1038/ng.2509

Rodriguez FJ, Perry A, Rosenblum MK, Krawitz S, Cohen KJ, Lin D, Mosier S, Lin MT, Eberhart CG, Burger PC (2012) Disseminated oligodendroglial-like leptomeningeal tumor of childhood: a distinctive clinicopathologic entity. Acta Neuropathol 124:627–641. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-1037-x

Rodriguez FJ, Schniederjan MJ, Nicolaides T, Tihan T, Burger PC, Perry A (2015) High rate of concurrent BRAF-KIAA1549 gene fusion and 1p deletion in disseminated oligodendroglioma-like leptomeningeal neoplasms (DOLN). Acta Neuropathol 129:609–610. doi:10.1007/s00401-015-1400-9

Sahm F, Reuss D, Koelsche C, Capper D, Schittenhelm J, Heim S, Jones DT, Pfister SM, Herold-Mende C, Wick W et al (2014) Farewell to oligoastrocytoma: in situ molecular genetics favor classification as either oligodendroglioma or astrocytoma. Acta Neuropathol 128:551–559. doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1326-7

Schweizer L, Koelsche C, Sahm F, Piro RM, Capper D, Reuss DE, Pusch S, Habel A, Meyer J, Gock T et al (2013) Meningeal hemangiopericytoma and solitary fibrous tumors carry the NAB2-STAT6 fusion and can be diagnosed by nuclear expression of STAT6 protein. Acta Neuropathol 125:651–658. doi:10.1007/s00401-013-1117-6

Taylor MD, Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Remke M, Cho YJ, Clifford SC, Eberhart CG, Parsons DW, Rutkowski S, Gajjar A et al (2012) Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol 123:465–472. doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0922-z

van den Bent MJ (2010) Interobserver variation of the histopathological diagnosis in clinical trials on glioma: a clinician’s perspective. Acta Neuropathol 120:297–304. doi:10.1007/s00401-010-0725-7

Wiestler B, Capper D, Sill M, Jones DT, Hovestadt V, Sturm D, Koelsche C, Bertoni A, Schweizer L, Korshunov A et al (2014) Integrated DNA methylation and copy-number profiling identify three clinically and biologically relevant groups of anaplastic glioma. Acta Neuropathol 128:561–571. doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1315-x

Wilcox P, Li CC, Lee M, Shivalingam B, Brennan J, Suter CM, Kaufman K, Lum T, Buckland ME (2015) Oligoastrocytomas: throwing the baby out with the bathwater? Acta Neuropathol 129:147–149. doi:10.1007/s00401-014-1353-4

Woehrer A, Slavc I, Waldhoer T, Heinzl H, Zielonke N, Czech T, Benesch M, Hainfellner JA, Haberler C, Austrian Brain Tumor R (2010) Incidence of atypical teratoid/rhabdoid tumors in children: a population-based study by the Austrian Brain Tumor Registry, 1996–2006. Cancer 116:5725–5732. doi:10.1002/cncr.25540

Wu G, Broniscer A, McEachron TA, Lu C, Paugh BS, Becksfort J, Qu C, Ding L, Huether R, Parker M et al (2012) Somatic histone H3 alterations in pediatric diffuse intrinsic pontine gliomas and non-brainstem glioblastomas. Nat Genet 44:251–253. doi:10.1038/ng.1102

Zhang J, Wu G, Miller CP, Tatevossian RG, Dalton JD, Tang B, Orisme W, Punchihewa C, Parker M, Qaddoumi I et al (2013) Whole-genome sequencing identifies genetic alterations in pediatric low-grade gliomas. Nat Genet 45:602–612. doi:10.1038/ng.2611

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the participants of the Consensus and Editorial Conference, held from June 21 through June 24, 2015 at the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) in Heidelberg, Germany, without whose input the 2016 CNS WHO edition would not have been possible. The participants were: Kenneth D. Aldape (Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, Toronto, Canada); Cristina R. Antonescu (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY); Mitchel Berger (University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA); Michael Brada (University of Liverpool Clatterbridge Cancer Centre, Wirral, United Kingdom); Daniel J. Brat (Emory University, Atlanta, GA); Peter C. Burger (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD); David Capper (Ruprecht-Karls Universität, Heidelberg, Germany); Webster K. Cavenee (University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA); V. Peter Collins (University of Cambridge Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, United Kingdom); Charles Eberhart (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD); David W. Ellison (St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN); Dominique Figarella-Branger (Hôpital de la Timone, Marseille, France); Gregory Fuller (MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX); Felice Giangaspero (Università di Roma “La Sapienza”, Rome, Italy); Caterina Giannini (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN); Takanori Hirose (Hyogo Cancer Center/Kobe University, Akashi, Japan); Cynthia Hawkins (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Ontario, Canada); Anne Jouvet (Hospices Civils de Lyon, Lyon, France); Paul Kleihues (University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland); Takashi Komori (Tokyo Metropolitan Neurological Hospital, Tokyo, Japan); Johan M. Kros (Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands); David N. Louis (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA); Roger E. McLendon (Duke University, Durham, NC); Ho Keung Ng (Prince of Wales Hospital, Hong Kong, China); Hiroko Ohgaki (International Agency for Research on Cancer/IARC, Lyon, France); Werner Paulus (University Hospital Münster, Münster, Germany); Arie Perry (University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA); Stefan Pfister (German Cancer Research Center/DKFZ, Heidelberg, Germany); Torsten Pietsch (University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany); Guido Reifenberger (University Hospital Düsseldorf, Düsseldorf, Germany); Brian Rous (Eastern Cancer Registration and Information Centre, Cambridge, United Kingdom); Andreas von Deimling (Institut für Pathologie, Heidelberg, Germany); Pieter Wesseling (VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands); Wolfgang Wick (University Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany); Otmar D. Wiestler (German Cancer Research Center/DKFZ, Heidelberg, Germany). The authors also thank many of the administrative staff who supported the meeting, particularly Esther Breunig from DKFZ and Kees Kleihues-van Tol, Asiedua Asante and Anne-Sophie Hameau from IARC, as well as Jessica Cox from IARC for help with establishing nomenclature styles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Louis, D.N., Perry, A., Reifenberger, G. et al. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 131, 803–820 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1