Hanseatic League

The first European Union?

Thousands of commuters pass through London's Cannon Street station every day. But only a few may be aware that this site once housed one of the most important trading centres in medieval Europe.

Behind the station on the banks of the River Thames, a street sign - Hanseatic Walk - gives a clue to the wealthy merchants who once dominated the area.

And on the red-brick wall of the Cannon Street railway bridge sits a plaque unveiled in 2005, commemorating “600 years during which time some 400 Hanseatic merchants inhabited peacefully in the City of London… a German self-governing enclave on this site”.

This was the London base of the Hanseatic League - a powerful trading network for hundreds of years, stretching all the way from the East of England to the heart of Russia.

It was one of the most successful trade alliances in history - at its height the League could count on the allegiance of nearly 200 towns across northern Europe.

London was never formally one of the Hanseatic cities, but it was a crucial link in the chain - known as a kontor or trading post. The community of German merchants who lived on the banks of the Thames were exempt from customs duties and certain taxes.

“At any given time they probably had about 15% market share of English imports and exports,” says Jens Tholstrup, an economist with a strong interest in the Hanseatic period.

Their reputation for reliability was such that it has often been suggested that the UK currency, Sterling, was a shortened form of “Easterling” - the local name for the Hanseatic traders.

This theory has been contested in recent years, but Tholstrup says the merchants nevertheless earned the trust of their English neighbours.

“It was a sign of their probity, that people trusted their currency. So when merchants here in England wanted to be paid in Easterling pounds, there was a sense that that was something they could rely on.”

The League’s London base was known as the Steelyard - probably because of the metal seals used to certify the origin of different types of cloth brought here for export.

The Steelyard - the Hanseatic League's London base

The Steelyard - the Hanseatic League's London base

None of its buildings - the warehouses, chapel, guildhall or residential quarters – remain. But as Alison Gowman, a City of London alderman, points out, their presence is revealed in place names - Steelyard Passage, running under Cannon Street station, or the Pelt Trader pub, beneath a railway arch.

“It’s opposite Skinners’ Hall where the fur trade was based, and the Pelt Trader has used that name as a reminder of one of the most important Hanseatic imports into London. It’s a fantastic link.”

The Steelyard came to dominate England’s cloth trade, and the wealth of its German merchants was captured in Hans Holbein’s 16th Century portraits.

Portraits of Hanseatic merchants by Hans Holbein The Younger (1497-1543)

Portraits of Hanseatic merchants by Hans Holbein The Younger (1497-1543)

Success also bred resentment and disputes with local traders, but it was an early example of pan-European co-operation. So to what extent can the Hanseatic League be seen as a forerunner of today’s European Union?

“People sometimes misuse the term and say the Hanseatic League promoted free trade. They absolutely did not. Their whole strategy was about creating monopolies and negotiating privileges,” says Tholstrup.

“But on the other hand, I think they created a network and developed prosperity at a time when the Baltic was a pretty bleak place. So the transformation they helped to generate was the origin of the prosperity of northwestern Europe.”

The League certainly did intervene at times in politics, supporting monarchs, imposing trade boycotts, and fighting wars. But Alison Gowman insists the primary objective was always financial.

“It was in order to keep their trade routes open. And, in that sense, it was about freedom to trade rather than free trade, and I think that is an important element of how the EU developed.”

What the League did not have, of course, was the kind of political and economic structures we now associate with the EU. But as the UK prepares for Brexit, could it provide a model for trading links in the years ahead?

Visby

Like Game of Thrones, the story of the Hanseatic League begins with the building of a wall.

In the second half of the 13th Century, the burghers of Visby - a town on the Swedish island of Gotland - built a mighty barrier to keep peasants out.

They wanted to protect the wealth that international trade was bringing to their town from across the Baltic Sea.

“Trading took place with privileged merchants - not with the farmers settled nearby,” says Lars Kruthof, local archaeologist and proud Gotlander. “And that is what we think the first wall was built for - to create customs posts.”

Local farmers would be forced to pay a tariff or tax if they wanted to sell their goods in the town. The wall provoked a civil war, and one sobering fact echoes through history - trade creates both winners and losers. It can be a brutal business.

More than 700 years later, the wall still stands - a reminder that the merchants of Visby were more interested in trading with their counterparts in other cities across the sea than with their own provincial neighbours.

Huge coin hoards found on Gotland, from the Arab world and Central Asia, testify to the town’s early importance in international trade.

“Since the Viking Age, trade was an important source of income for people on Gotland,” says the Swedish historian Erika Sandstrom.

But Visby is also a reminder that fortunes ebb and flow, and these days it relies on that most modern form of trade - tourism. The harbour that generated so much of its medieval wealth is now a peaceful local park overlooking the Baltic sea.

In the surrounding streets, tourists flock to the tall brick warehouses with staircased roofs, remnants of the once-mighty trading network that dominated northern Europe.

“For a medieval person, who had never been to a town, to see this would probably be the same as me going to New York for the first time to see the skyline of Manhattan,” says Kruthof.

Marvelling at the sense of scale and ambition, he describes the kind of goods that would have been traded in Visby: “Textiles from different parts of the world, spices, saffron and salt-glazed pottery from Germany… and of course the squirrel skins from Novgorod, the most important trading good in this area.”

As the medieval world opened up, Visby began to connect with other parts of the Baltic region, and the wide-ranging network of merchants and subsequently towns which became the Hanseatic League, was born.

Visby was one of its first centres of power. Local merchants, trading with their counterparts in northern Germany in particular, formed guilds or Hansas to further their interests and build their networks.

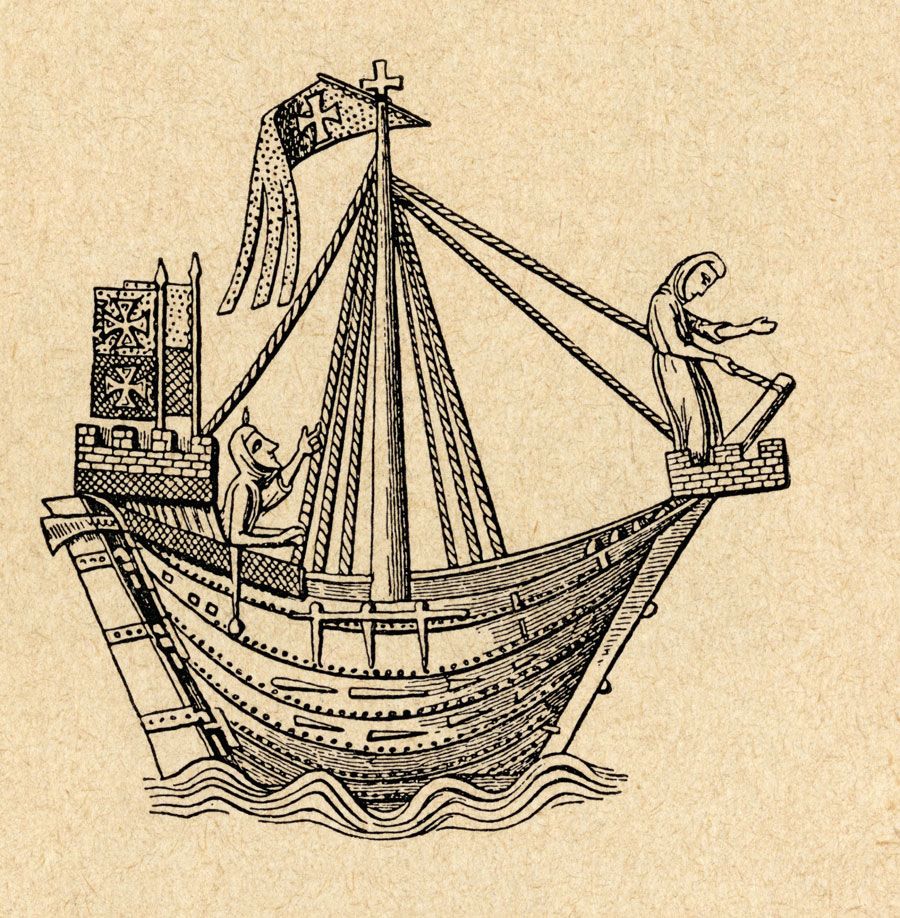

A 14th Century Swedish woodcut of a Hanseatic League ship

A 14th Century Swedish woodcut of a Hanseatic League ship

“It was an organisation protecting trade for some merchants,” says Sandstrom. “They weren’t free traders.”

But they were successful.

One of the big prizes of Baltic trade was the skin of the humble Russian squirrel.

Huge consignments of squirrel skins were exported from the Russian port of Novgorod to meet the insatiable demand for fur-trimmed cloaks and other fashionable garments.

It was so lucrative that others wanted a slice of the action - and not for the last time in European history, this became an issue of German dominance.

“Visby had had the trading with Novgorod and it prospered,” Kruthof explains. “But then the Germans came to Visby, the Germans settled in Novgorod, and they slowly took over the trade.”

Other factors challenged Gotland’s dominant position - piracy, better methods of navigation, ships that could travel further and faster, and military attacks from Denmark.

Visby couldn’t control what it had created, and while the town had its moment of glory, it was eventually bypassed. But the co-operation between ambitious merchants, pioneered in Gotland, had grown gradually into an organised network - a medieval trading superpower.

Lübeck

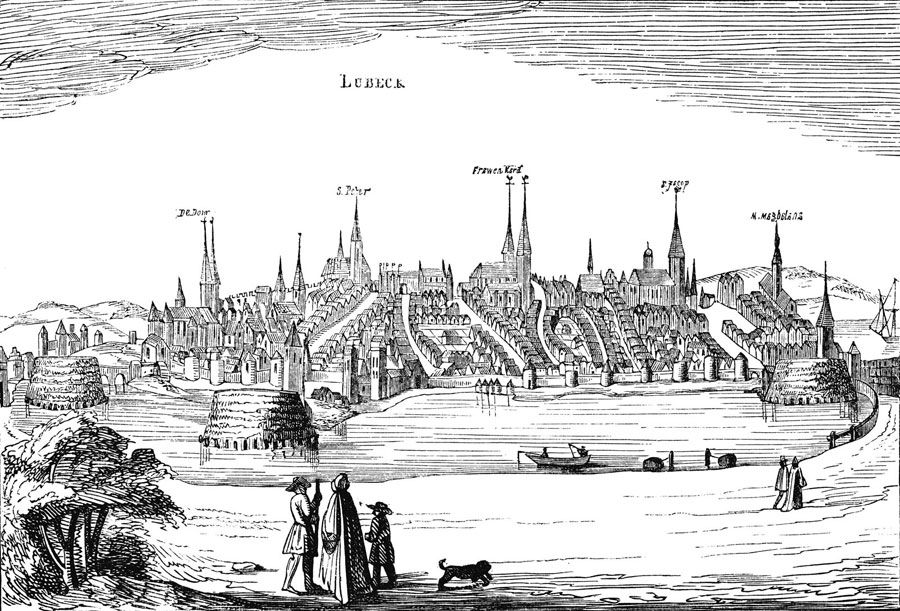

Lübeck is sometimes called the city of the seven spires. Soaring medieval churches dominate its skyline, and help define its history.

Some of that history is relatively recent - in St Mary’s Church the broken bells of the South Tower still lie embedded in the ground, where they fell during an allied air raid in 1942.

St Mary's Church, Lubeck

St Mary's Church, Lubeck

But Lübeck had its heyday at the heart of the Hanseatic world. Between 1356 and 1669 it hosted more than 100 meetings of the Hansetag, the assembly which brought representatives of Hanseatic towns together to plot strategy and advance their interests.

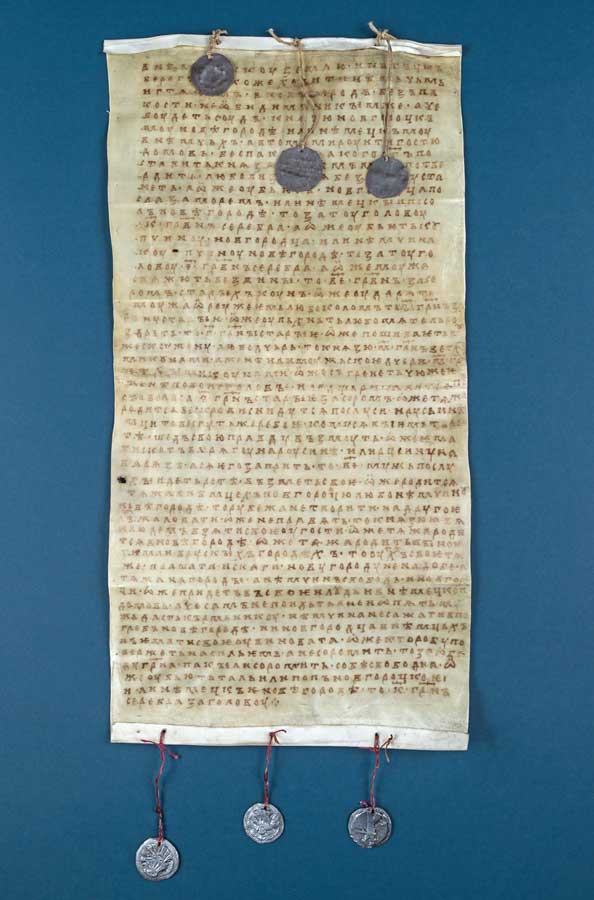

The story of their shared history is now on display in the exhibition rooms of the city’s European Hansemuseum. Digital maps on the walls, and facsimiles of early trade contracts, plot the development of this new world.

Trade agreement signed in Russia, 1259, by Prince Alexander Nevsky and German merchants, stipulating that German weights are to be used to regulate trade in the future (Hansemuseum)

Trade agreement signed in Russia, 1259, by Prince Alexander Nevsky and German merchants, stipulating that German weights are to be used to regulate trade in the future (Hansemuseum)

“In the beginning it was very much about conducting long distance trade,” says Angela Huang, the museum’s research director, “and about forming a community of merchants abroad.

“In the 11th to 13th Centuries you have an expanding economy - towns are founded, markets grow, and the population of Europe grows quite remarkably during that period.”

The Hansemuseum was opened four years ago by Chancellor Angela Merkel, a reminder that Hanseatic history really matters in these parts. In her speech at the opening ceremony the Chancellor described the Hansa as a role model for the EU.

Angela Merkel at the inauguration of the Hansemuseum

Angela Merkel at the inauguration of the Hansemuseum

The legacy of the Hanseatic period endures all along Germany’s Baltic coast.

Both Hamburg and Bremen are still known officially as free Hanseatic cities, and are states in their own right in the German federal republic. Further east along the coast the local football team is called Hansa Rostock, while the name of the national airline - Lufthansa - also commemorates past trading glories.

But Lübeck was the “Queen of the Hansa”, at the heart of a network which stretched not only across the water but also inland, providing all manner of goods, such as wax from eastern Europe, and herring from Scandinavia, to thriving towns in the interior.

Pride of place in one room at the museum is given to the reproduction of a wooden cog, the distinctive Hansa ship with its square-rigged single sail. The cog was developed for the burgeoning trade routes across the Baltic, and was in effect an early forerunner of the modern container ship.

“This was not a ship that was made for raiding or for conflict, it was a transport vessel, quite slow,” Huang observes. “Its main function was that it could transport commodities in bulk.”

A replica of a 15th Century cog

A replica of a 15th Century cog

And as trade developed, towns which were hundreds of miles apart needed reassurance that they were all getting value for money and a fair deal. So, they created a system of common standards and regulations.

An agreed schedule of weights and measurements was particularly important, and the museum has several examples on display.

“At the time there was so much insecurity in trade, says Huang. “You’re meeting at the market with a ball of cloth, but how do you decide how much it is worth? It was necessary to have common standards to avoid conflicts, so you and I can agree on what you’re selling me, and for what price.”

Displays in Lübeck's Hansemuseum

Displays in Lübeck's Hansemuseum

Imitation was also a big problem, so there was plenty of regulation about the type of cloth, for example, that could be traded - it had to be stamped or sealed or folded in the right way.

The Hanseatic League, in other words, was active in quality control. Highly prized cloth from Bruges or Leiden would be trademarked, even though there was no international law that prevented the copying of another product.

“It was important for merchants,” says Huang, “that the commodity that arrived in Novgorod, that they wanted to sell on to Russian merchants, was actually what they claimed it to be – because there might be hell to pay if not.”

In fact, many of the issues that dominate modern trade discussions - counterfeit goods, trademarks and (for trade geeks) even “rules of origin” - echo the Hanseatic period.

Sometimes, of course, disputes emerged, and even natural trading partners fell out. But the Hanseatic League endured for a remarkably long time because it helped guarantee quality, organise logistics and create trust.

16th Century Lübeck

16th Century Lübeck

Eventually, inevitably, the tide of history began to turn, and a number of big factors saw the Hansa gradually lose influence. The rise of nation states as centres of political power challenged its trading model, as did the emergence of new markets and trade routes around the world.

Even modern-sounding ideas like climate change played their part, as shoals of herring, a key Hanseatic commodity, moved out of the Baltic in the 15th Century in search of warmer waters elsewhere.

The Thirty Years’ War which devastated central Europe in the 17th Century was perhaps the final straw. But a belief in the Hanseatic model of co-operation rarely wavered, and the maritime culture at the heart of the Hansa is still strong in Lübeck today.

You get a sense of that at the top of Engelsgrube, the street that looks down the hill towards the Trave river. It used to be known as the English Road, leading down to the quay where the ships bound for England were moored.

Warehouses along the Trave River

Warehouses along the Trave River

English towns and cities were never a formal part of the Hanseatic League. Even in medieval times English merchants were semi-detached from the dominant European network of the day.

But memories of the Hansa still persist in unexpected corners of England.

King's Lynn

The last surviving Hanseatic building in England is a brick warehouse on the banks of the Great Ouse in King’s Lynn, on the Norfolk coast.

“We have old letters from German merchants in London,” says Dr Paul Richards, a local historian, “saying how well they were treated in Lynn. The Germans had a favourite pub in Lynn, a big inn in Norfolk Street called The Swan.”

It is pretty quiet by the river now, but in the Middle Ages this was a port that served 10 counties in the interior. The Lynn kontor was run mainly by merchants from Danzig (now Gdansk in Poland), importing wax and pepper.

“It was a Hanseatic community in England, and they did deals and got on very well with the Lynn merchants,” Richards says. “Of all the English towns... Lynn kept up the Baltic link.”

Over the past few years those links have been reborn as towns across Europe have created a network called the New Hanseatic League or the Hanse. King's Lynn was the first British town to join (Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Boston and Hull are among the other members).

“It’s about pageantry, and about raising awareness of the past,” says Richards, “but it’s also about the future.”

King's Lynn celebrates its Hanseatic links with pageants such as this one in 2015

King's Lynn celebrates its Hanseatic links with pageants such as this one in 2015

The Hanse can, for example, put a specialist flooring company in King’s Lynn in touch with timber merchants in Estonia or Latvia. The Latvian ambassador to the UK, Baiba Braže, argues that the Hanseatic League does provide a model to aspire to.

“If we look back at European history we can see periods where the same type of thing repeats itself in different incarnations,” she says, “because it has provided a mass of power.”

And while the Brexit process grinds on, those old links are also being revived on a political level within the EU. A group of northern countries including the Netherlands, Ireland and the Scandinavian and Baltic states have also started calling themselves the New Hanseatic League.

Broadly speaking, they want to promote free markets and conservative fiscal policies, as a bulwark against more protectionist policies emerging from southern Europe.

They feel comfortable with each other, and they are beginning to exert influence on the direction of European economic reform. But they also worry about losing the UK, their most influential ally in the room.

“We are really very sorry to lose the UK as a like-minded voice in the European Union,” admits Braže. “We don’t want to see you go because we think we are all stronger when we stick together.”

But beyond the high politics of leaving the EU, towns are continuing to forge links of their own.

The recently retired mayor of King’s Lynn, Nick Daubney, was proud to become the first British commissioner to the New Hanseatic League.

“I did inform the Foreign Office,” he smiles, “but I never had any reply.

“I’m now the English commissioner because Aberdeen joined, and it was felt that Scotland should have its own identity in the Hanseatic League. So I was demoted.”

At first sight there is a degree of irony that an area that voted so heavily for Brexit is so keen to create new links with Europe. In the 2016 referendum, Leave won 66.4% of the vote in King’s Lynn and West Norfolk.

But locals argue that Brexit makes efforts to restore Hanseatic links even more appropriate. Politically this area may have made it very clear that it didn’t want to remain part of the EU, but it didn’t vote for isolation.

“This is not about international politics,” Daubney insists. “It’s about people who like each other, people who want to trade with each other, people who want to visit each other. And we will promote those ideals whatever happens.”

As if to back up his argument, outside on the quayside I bump into Angela Huang, the research director from Lubeck, next to a sculpture which commemorates the trade in dried fish that Hanseatic merchants used to bring to Lynn across the North Sea from Norway.

She’s come to King’s Lynn to give a lecture on aspects of Hanseatic co-operation.

Sculpture in King's Lynn commemorating the trade in dried fish

Sculpture in King's Lynn commemorating the trade in dried fish

“I’ve never been so much into Kings or Popes, but towns do fascinate me,” she says.

“I think it’s so interesting to see how they worked together on such a scale for such a long time, shaping our society very profoundly.”

Whether via towns or cities or national governments, the UK is going to be thinking a lot more about trade in the coming years, as it tries to forge a new relationship with the rest of Europe, and with the rest of the world.

The ability to forge a trade policy independent of the EU has always been sold as one of the big benefits of Brexit, and the Hanseatic League serves as a reminder that trade tends to continue even amidst much turmoil.

But there is another lesson from history - that trade can be a school of hard knocks.

It is also an expression of power, and of how we find our own place in the world.

Chris Morris's BBC Radio 4 documentary, The Hansa Inheritance, can be downloaded from BBC Sounds