The Redskins are celebrating their 75th anniversary this year. The team’s life span takes in 13 US presidents, five NFL championships, and four colorful team owners.

If you’d been around 75 seasons ago, you’d have seen a Redskin team playing in leather helmets and high-top shoes, bankrolled by a millionaire who was often called arrogant and abrasive.

That would be George Preston Marshall, the team’s founder, who brought the franchise here from Boston in 1937.

Owner of a local laundry chain, Marshall, along with the Chicago Bears’ George Halas, was one of the patriarchs of the National Football League.

What set Marshall apart from Halas was that Marshall wasn’t so much a football man as a huckster with a flair for show business. He married a Hollywood actress, Corinne Griffith, and together they fashioned a new business model for selling professional football not just as a game but as a Sunday-afternoon spectacle.

Until Marshall came along, the pro game was far down the list of sports in popularity. Football was considered an elitist college pastime. Pro players earned $200 to $300 a game; the NFL championship was a second-tier sports story in comparison with the college Rose Bowl game.

For a salesman like Marshall, the marketing answer was obvious: Surround the Sunday game with the sis-boom-bah seen and heard at Saturday college games. Marshall introduced the marching band, the fight song, sideline cheerleaders, and halftime pageantry to pro football in the 1930s. He liked to call himself the Big Chief of the Redskin Nation.

Marshall’s legacy as the first owner of the Washington Redskins is blighted by his being the last holdout against integrating the National Football League. With a one-team monopoly on NFL television rights in the South—the original words to the Redskins song were “fight for old Dixie,” not “fight for old DC”—the Washington owner resisted signing black players until ordered to by the league.

The arrival of All-Pro Bobby Mitchell in Washington for the 1962 season not only broke the color barrier but lifted the spirits of long-suffering Redskins fans. Mitchell would go on to become an NFL Hall of Famer and Redskins executive when his playing days were over.

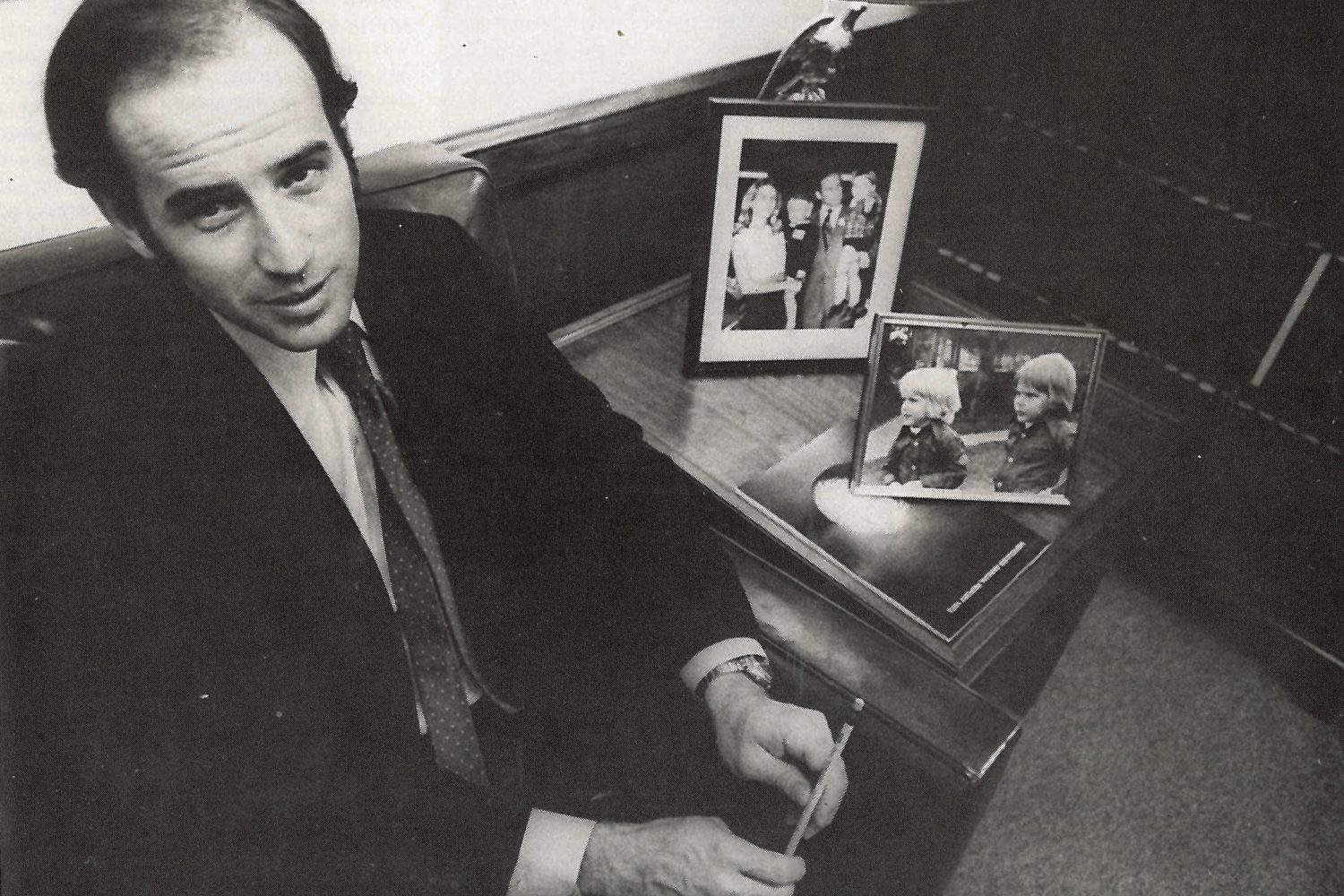

High-powered lawyer Edward Bennett Williams, who took over the Redskins after Marshall became seriously ill in 1965, was a minority stockholder, but he ran the franchise during the 1960s and ’70s while the majority stockholder, Jack Kent Cooke, lived in Los Angeles, where he ran his basketball team, the NBA’s Lakers.

Williams brought the same passion for winning to the football stadium that he brought to the courtroom. In 1969 he lured the legendary Vince Lombardi out of retirement to coach the Redskins to the team’s first winning year in more than a decade.

After Lombardi died of cancer in 1970, Williams hired another coach with a winning record, George Allen, who ushered in the era of the Over-the-Hill Gang—and Washington’s first Super Bowl appearance, in January 1973.

But the superlawyer’s days of running the team were numbered. With the sale of the Los Angeles Lakers, Jack Kent Cooke moved east to take over the Redskins, and Williams turned his attention to baseball and running the Baltimore Orioles.

A transplanted Canadian with a penchant for Olde English ways, Jack Kent Cooke was called the Squire of Middleburg. Sportswriters found him arrogant and patronizing—but he was the ideal team owner for a town hungry for a winner.

A self-made media multimillionaire, Cooke was above all a businessman. But unlike other self-made millionaires who buy NFL teams, he had no problem deferring to the expertise of others, in this case general manager Bobby Beathard and coach Joe Gibbs, in running his ball club. The result was three Super Bowl trophies, a tough act for the next Redskins owner to follow.

Next year will mark the tenth anniversary of Dan Snyder’s record $800-million purchase of the Redskins from the trust set up in Cooke’s will. Like Marshall and Cooke, Snyder is sometimes called arrogant and patronizing, but the team’s fourth owner has something of Marshall’s showman’s flair, Ed Williams’s passion to win, and Cooke’s willingness to spend money.

Yet even with Joe Gibbs back on the sidelines and with one of the biggest payrolls in the league, Snyder hasn’t succeeded in bringing a Super Bowl trophy back to old DC.

True, we still have the Redskins band and the Redskinettes to cheer us at halftime, not to mention the diversion of Tom Cruise, shades and all, up front in the owner’s box. George Marshall would love the show, but Ed Williams and Jack Kent Cooke might be able to teach Dan Snyder a thing or two about building a winner.