Abstract

Objective

To present findings of a narrative review on the implementation and effectiveness of 17 Articles of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) during the Treaty’s first decade.

Data sources

Published reports on global FCTC implementation; searches of four databases through June 2016; hand-search of publications/online resources; tobacco control experts.

Study selection

WHO Convention Secretariat global progress reports (2010, 2012, 2014); 2015 WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic; studies of social, behavioural, health, economic and/or environmental impacts of FCTC policies.

Data extraction

Progress in the implementation of 17 FCTC Articles was categorised (higher/intermediate/lower) by consensus. 128 studies were independently selected by multiple authors in consultation with experts.

Data synthesis

Implementation was highest for smoke-free laws, health warnings and education campaigns, youth access laws, and reporting/information exchange, and lowest for measures to counter industry interference, regulate tobacco product contents, promote alternative livelihoods and protect health/environment. Price/tax increases, comprehensive smoking and marketing bans, health warnings, and cessation treatment are associated with decreased tobacco consumption/health risks and increased quitting. Mass media campaigns and youth access laws prevent smoking initiation, decrease prevalence and promote cessation. There were few studies on the effectiveness of policies in several domains, including measures to prevent industry interference and regulate tobacco product contents.

Conclusions

The FCTC has increased the implementation of measures across several policy domains, and these implementations have resulted in measurable impacts on tobacco consumption, prevalence and other outcomes. However, FCTC implementation must be accelerated, and Parties need to meet all their Treaty obligations and consider measures that exceed minimum requirements.

Keywords: global health, prevention, public policy

Introduction

Tobacco use is a leading cause of premature mortality and disease burden worldwide, resulting in approximately seven million preventable deaths annually.1–3 It is estimated that if current trends continue, tobacco will kill more than eight million people globally each year by 2030, with 80% of premature deaths occurring in low-income and middle-income countries (LMICs).4–7

In response to the globalisation of the tobacco epidemic, the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) was adopted by the World Health Assembly in 2003 and entered into force in 2005. The FCTC is one of the most widely adopted United Nations (UN) Treaties, with 181 Parties as of May 2018. It provides a comprehensive strategy for Parties to combat the tobacco epidemic and sets out a broad range of evidence-based measures to reduce tobacco demand (Articles 6–14) and supply (Articles 15–17).8 9

The year 2015 marked the tenth anniversary of the FCTC coming into force, as well as the introduction of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a comprehensive set of health-related goals and targets for all countries to achieve by 2030. Over the last decade, the prevalence of tobacco use has declined in countries with policies that align with or exceed the minimum requirements of the FCTC and its guidelines.10–13 Nevertheless, recent evidence suggests that many countries are not on track to achieve the WHO target of a 30% relative reduction in adult tobacco use by 2025.14 15

A decision by the FCTC Conference of the Parties (COP) at its sixth session in Moscow in October 2014 (FCTC/COP6(13)) established an independent group of seven experts to conduct an impact assessment to ‘examine the impact of the WHO FCTC on the implementation of tobacco control measures and on the effectiveness of its implementation’ over the first decade of the Convention.16 As of 2017, the WHO Convention Secretariat has published seven reports on global progress in FCTC implementation,17–23 and the WHO has published six reports that track the status of the global tobacco epidemic and policy interventions.24

Existing literature reviews of the FCTC’s impact focus on the evaluation of key measures to reduce the demand for tobacco: monitoring tobacco use; smoke-free laws; tobacco cessation interventions; health warnings; tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship (TAPS) bans; and tobacco tax increases. A systematic overview by Hoffman and Tan25 identified 59 systematic reviews summarising over 1150 primary studies (up to May 2015) on the impact of FCTC policies on tobacco use, second-hand smoke (SHS) exposure and primary health outcomes. Evidence was strongest for the effectiveness of smoke-free and tobacco taxation policies, followed by mass media campaigns and health warnings on the harms of tobacco use, and affordable smoking cessation treatment interventions; limited for advertising restrictions; and unavailable for monitoring tobacco use. A recent review of 41 studies (up to June 2017) on the effect of key demand-reduction measures on perinatal and child health found that smoke-free legislation was consistently associated with positive child health outcomes, including lower rates of preterm birth, and hospital admissions for childhood asthma and respiratory tract infections, with stronger associations for comprehensive bans than partial bans.26

It is estimated that nearly 22 million future premature smoking-attributable deaths were averted as a result of strong implementation of demand-reduction measures adopted by countries between 2007 and 2014.27 Consistent with this, Dubray et al 10 found that overall, countries with higher levels of implementation on these key measures experienced greater decreases in current tobacco smoking between 2006 and 2009. Similar findings on the positive effects of these demand-reduction measures on reducing smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption during 2007–2014 were found in another study by Ngo et al.28 A recent study by Gravely et al 29 found that increases in highest level implementations of the five key FCTC demand-reduction measures between 2007 and 2014 were significantly associated with a decrease in smoking prevalence between 2005 and 2015.

While there is a large evidence base for the effectiveness of these core demand-reduction measures, little is known about the impact of other FCTC policies, such as supply-reduction measures to reduce illicit tobacco trade, prohibit sales to and by minors and promote alternative livelihoods. Under decision FCTC/COP6(13),30 desk reviews of existing literature on the impact of the FCTC were mandated as a part of the work of the Expert Group (EG). In 2015–2016, the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation Project (ITC Project) conducted a global evidence review of the impact of the FCTC on the implementation of tobacco control legislation and the effectiveness of those implementations across a much broader set of FCTC policy domains. Further details on other literature reviews prepared for the EG as well as the methodology used by the EG to conduct the FCTC impact assessment are provided in this volume. In brief, the ITC global evidence review was prepared to inform the EG in deliberations at its first meeting (Geneva, August 2015). The global evidence review played a central role in the work of the EG by providing the context for the preparation of briefing materials on the status of FCTC implementation for the 12 country missions, and serving as a main evidence source for the EG’s report on their findings of the impact assessment to the COP at its seventh session (COP7; New Delhi, November 2016). The EG’s final report, ITC global evidence review and other relevant materials are available on the WHO Convention Secretariat website: http://www.who.int/fctc/cop/cop7/Documentation-Supplementary-information/en/.

This paper summarises the ITC global evidence review, which represents the most comprehensive overview and assessment of FCTC impact to date across the Treaty’s first decade. Given the limited time frame that was available (May–July 2015 for completion of literature review for EG’s first meeting on 10–11 August 2015; June 2016 for updates to correspond with the time of the EG’s submission of their final report of findings of the impact assessment to the COP on 29 June 2016), this review is not a systematic review of all available evidence on the implementation and effectiveness of policies called for under the 17 FCTC Articles. Rather, it is a narrative review that aims to provide a qualitative synthesis of evidence on whether the FCTC has increased and strengthened the implementation of tobacco control policies under the 17 Articles of the Convention and the effectiveness of those measures. A narrative review provides a qualitative summary of primary studies on a research question, covers a wide range of issues on a topic, and allows for the inclusion of a broad range of evidence sources that use different study designs and report diverse outcomes,31 32 and is thus well suited for the purpose of the current review.

Methods

This narrative review was conducted across 17 substantive Articles of the FCTC, where impact assessment was appropriate (table 1 provides a brief description of each Article, and further details are provided in online supplementary table S1). i The 2010, 2012 and 2014 global progress reports on FCTC implementation prepared by the WHO Convention Secretariat20–22 and the 2015 WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic33 served as the primary sources to assess global progress and key challenges in FCTC implementation. Relevant data from published studies and policy reports were also included. Based on an overall assessment of available sources (up to June 2016) on changes in the total number of countries/FCTC Parties who reported the implementation of Treaty provisions over time, the level of progress for each Article was categorised as higher (significant and rapid progress), intermediate (some progress but slower overall rate, with advancements often limited to partial implementation) or lower (some momentum to support the development of measures but slow progress).

Table 1.

Brief description of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) Articles included in this review

| FCTC Article | Description |

| Article 5.3 | Protect tobacco control policies against industry interference. |

| Article 6 | Price and tax measures to reduce tobacco consumption, including raising the price of tobacco products through taxation, prohibiting/restricting tobacco sales to international travellers and dedicating tobacco tax revenues to fund tobacco control. |

| Article 8 | Protection from exposure to tobacco smoke in indoor public places, workplaces, public transport and other public places. |

| Article 9 | Regulation of tobacco product contents through testing and measuring contents and emissions of tobacco products. |

| Article 10 | Regulation of tobacco product disclosures by requiring tobacco manufacturers and importers to disclose information about contents, toxic constituents and emissions of their products. |

| Article 11 | Require health warnings on tobacco product packaging and prohibit misleading tobacco packaging and labelling. |

| Article 12 | Use all available communication tools to promote education, communication, training and public awareness of tobacco control issues. |

| Article 13 | Enforce comprehensive bans on all forms of tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship. |

| Article 14 | Promote tobacco cessation and provide treatment for dependence through healthcare providers, and accessible, low-cost interventions. |

| Article 15 | Eliminate all forms of illicit trade in tobacco products, including smuggling, illicit manufacturing and counterfeiting. |

| Article 16 | Prohibit sales of tobacco products to and by minors, including a ban on the sale of tobacco products at point of sale, restrictions on accessibility to tobacco vending machines and ban on the sale of single cigarettes or small packs. |

| Article 17 | Promote economically viable alternatives for tobacco workers, growers and individual sellers. |

| Article 18 | Protect the environment and health of persons with respect to the cultivation and manufacturing of tobacco. |

| Article 19 | Legislative action to deal with criminal and civil liability, including compensation where appropriate. |

| Article 20 | Research, surveillance and exchange of information on tobacco control, including patterns of, determinants and outcomes of tobacco consumption. |

| Article 21 | Require Parties to submit periodic reports on implementation of the Convention. |

| Article 22 | International cooperation to promote the transfer of technical, scientific and legal expertise and technology to establish and strengthen national tobacco control strategies. |

tobaccocontrol-2018-054389supp001.pdf (280.7KB, pdf)

Published studies and grey literature on the effectiveness of FCTC measures were identified from searches of four electronic databases: PubMed, Cochrane Library, Scopus and Google Scholar. Independent searches were conducted by three authors (JC-H, SG, NS) and screened by all coauthors between May and July 2015. Searches were updated by the lead author (JC-H) in June 2016 and reviewed by the second author (LC). Tobacco control experts (online supplementary table S2) were also contacted to identify further sources. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were primary or secondary research on the social, behavioural, health economic and/or environmental impacts of FCTC tobacco control policies. Searches were conducted for the full time period available up to June 2016. Non-English-language studies and tobacco industry-funded research were excluded. A broad range of general and FCTC Article-specific search terms were used for all databases to capture as many publications on the effectiveness of FCTC measures as possible. Additional materials were identified by hand-searching selected peer-reviewed publications and grey literature, and scanning online resources created by leading tobacco control advocacy/research groups, such as the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, Framework Convention Alliance, University of California San Francisco Truth Tobacco Industry Documents and Tobacco Tactics.

tobaccocontrol-2018-054389supp002.pdf (102.9KB, pdf)

A total of 128 studies, identified in consultation with a panel of tobacco control experts, were included in this review.

Results

Impact of FCTC on tobacco control legislation

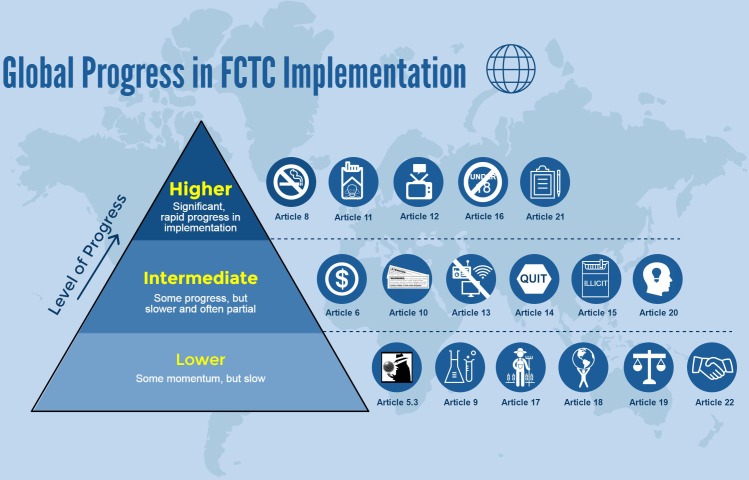

FCTC implementation reports submitted by Parties to the Convention Secretariat show progress in the implementation of tobacco control legislation since the Convention came into force in 2005. However, there is considerable variability in the overall rate and extent of progress in the implementation of tobacco control legislation across countries and policy domains, with limited progress in the implementation of strong policies in many LMICs. Figure 1 summarises overall progress in the implementation of measures for each of the 17 FCTC Articles.

Figure 1.

Global progress in Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) implementation based on available sources up to June 2016.

The FCTC has contributed to significant and rapid progress in the implementation of the following:

Comprehensive smoke-free laws for indoor workplaces, restaurants and bars (Article 8).22 33 34

Larger, pictorial health warnings on cigarette packages (Article 11).35–38

Mass media education campaigns on the health risks of tobacco consumption and exposure to tobacco smoke, and the benefits of quitting (Article 12).20 22

Bans on the sale of tobacco products to and by minors (Article 16).22 39 40

Since the first reporting cycle in 2007, there has also been a steady increase in the number of Parties that have submitted FCTC implementation reports in accordance with Article 21.22

The FCTC has contributed to some progress in the implementation of the following:

Tobacco price and tax increases,22 33 simplified tax systems41–43 and tax measures that account for inflation (Article 6).44–47

Disclosure of information on the contents and emissions of tobacco products (Article 10).22

Comprehensive TAPS bans (Article 13).33

Cessation services (Article 14).20 22 33

Measures to counter illicit tobacco trade (Article 15).22

Programmes for tobacco-related research, surveillance and information exchange (Article 20).22 48

However, overall global progress in these policy domains has been slow and advancements have often been limited to partial implementation.

Finally, the FCTC has generated momentum, in a small number of countries, to support the development of measures to:

Protect tobacco control policies from industry interference (Article 5.3).22

Regulate the contents and emissions of tobacco products (Article 9).22

Promote economically viable alternatives for tobacco farmers (Article 17).20 22 49 50

Address the health and environmental impacts related to the cultivation and manufacture of tobacco (Article 18).22 51

Allow for legislative action against the tobacco industry (Article 19).22 52

Facilitate international cooperation (Article 22).21 22

Ongoing challenges to the implementation of the FCTC

The FCTC has generally had a positive impact on tobacco control. Nevertheless, there are a number of ongoing challenges to the effective implementation of the Convention.

Tobacco industry interference

The tobacco industry has a long-standing history of using direct and indirect tactics to obstruct, delay or weaken the implementation of FCTC policies, including smoke-free laws, tobacco marketing bans, and price and tax measures.53–57 Although an increasing number of countries have taken steps to prevent tobacco industry interference (TII) with policymaking in recent years, no country has fully implemented measures to protect public health policy from TII at the best practice level as recommended under Article 5.3 to date.3 23 33 58 As a result, TII continues to be the largest barrier to FCTC implementation worldwide. The tobacco industry continues to use strategies that are in violation of Article 5.3 guidelines, including government partnerships,59 60 front groups61–63 and corporate social responsibility activities,64 as well as strategies that are not directly covered by Article 5.3 guidelines to interfere with policymaking. For example, the industry has used trade and investment agreements to challenge legislation for plain packaging in Australia and larger health warnings in Uruguay.57 65–68 The industry has also established ‘Better Regulation Agendas’ to promote their interests and block the implementation of evidence-based policies, such as the 2014 Tobacco Product Directive in the European Union and plain packaging in the UK.63 69 70

It is encouraging, however, that such industry tactics have been unsuccessful. Notably, legal challenges to legislation for plain packaging in Australia and the UK, and 80% front and back pictorial warnings and single brand presentation in Uruguay, have all been dismissed by domestic and international courts/tribunals.71–76 These landmark rulings reinforce that governments have the right to implement FCTC measures for the protection of public health and are expected to set a strong precedent for the introduction of similar legislation in other countries.77 78

Lack of guidelines and ineffective implementation of existing guidelines

In general, progress in FCTC implementation has been more rapid and comprehensive for Articles with existing guidelines and specified timelines for implementation of certain provisions. Formal guidelines have not yet been adopted to assist Parties to meet their Treaty obligations under Articles 9, 10, 15 and 17–22. Selective and incomplete implementation of existing guidelines allows the tobacco industry to take advantage of loopholes in existing legislation, thus weakening the policy impact. For example, few countries earmark tobacco tax revenues for health purposes; prohibit smoking in private workplaces, pubs and bars, and private motor vehicles; have health warnings covering more than 50% of the package; prohibit tobacco displays at point of sale; and mandate the recording of patients’ tobacco use in medical notes.22 33 79

Insufficient capacity and lack of financial support

In many countries, there is limited capacity for tobacco control at the national level. For example, Parties have identified the lack of capacity for testing contents of tobacco products and national data collection as barriers to the implementation of Articles 9 and 21, respectively. As of 2014, only 5 of 130 reporting Parties have established training programmes and strategies that aim to strengthen tobacco control capacity, as called for under Article 20.22 In most countries, governments provide limited (if any) financial support for core FCTC measures, including cessation services and tobacco dependence treatment,33 80 alternative livelihood programmes,81–84 measures for the protection of the environment and health of tobacco workers,22 51 and tobacco-related research programmes.48

Poor enforcement

In the vast majority of countries, there are weak enforcement mechanisms to ensure compliance with tobacco control policies. For example, many Parties continue to experience enforcement-related difficulties for smoke-free laws, TAPS bans and youth access laws.21 22 37

Effectiveness of FCTC-compliant tobacco control measures

There is a growing body of research on the effectiveness of tobacco control measures that align with the FCTC and its existing guidelines. This narrative review included 128 studies on the effectiveness of FCTC measures up to June 2016 (online supplementary table S3). Overall, studies on the impact of price and tax increases (n=6),22 44 85–88 comprehensive smoke-free policies (n=17),13 89–104 health warnings (n=25),105–129 comprehensive TAPS bans (n=14)130–143 and cessation interventions (n=19)79 144–161 consistently found that these are among the most effective strategies to reduce tobacco consumption/prevalence and tobacco-related health risks, and encourage quitting. Studies conducted in high-income countries (HICs) also provide strong evidence that mass media campaigns (n=14)162–175 and well-enforced measures to restrict youth access to tobacco products (n=10)176–185 are effective for preventing smoking initiation, decreasing smoking prevalence and promoting cessation.

tobaccocontrol-2018-054389supp003.pdf (407.2KB, pdf)

A small number of case studies provide evidence for the effectiveness of coordinated national strategies to combat illicit trade in the UK, Spain and Kenya (n=4)33 186–188; profitability of small-scale alternative crop programmes in China, Kenya, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Bangladesh and Brazil (n=9)189–197; and reductions in green tobacco sickness among tobacco workers who used personal protective equipment in the USA, India and Malaysia, as well as those who were exposed to a public education campaign on the risks of tobacco harvesting in the USA (n=7).198–204 One study found that regular monitoring of tobacco use is associated with a decrease in smoking rates over time.10 Two reviews summarised the use of the FCTC and its guidelines in legislation and litigation, and showed an increase in the number of countries who have used the Treaty to support new tobacco control policies and to defend legislation against industry challenges.52 205

No studies evaluating the impact of measures for prevention of industry interference, regulation of contents of tobacco products, and facilitation of information exchange and cooperation were identified.

Discussion

This narrative review is the first to synthesise global research evidence on the impact of the FCTC after its first 10 years. It is the broadest assessment to date of whether the implementation of tobacco control legislation across 17 substantive Articles could be attributed to the FCTC, and whether implementation of those policies was linked to subsequent changes in tobacco consumption, prevalence and other tobacco-related outcomes.

The findings of the review were integral to the work of the EG, as they provided background and context for the country missions, and evidence that informed the judgements of the EG in their report to COP7 on the outcome of the impact assessment and recommendations on how to strengthen FCTC impact. Leading tobacco control experts were engaged in the literature review process and made contributions to gathering and reviewing evidence on the effectiveness of the implementation of the Convention.

The FCTC impact assessment contributed to building the foundation for shifting the focus of the COP from increasing ratification and guideline development towards actions to encourage accelerated implementation of the FCTC, including the establishment of an implementation working group under a decision adopted at COP7 (FCTC/COP7(13)).206

Overall, this review shows that tobacco control policies are effective when they are implemented according to the Treaty and its guidelines. However, the overall rate and extent of global progress in the implementation of the provisions of the Convention remain uneven across countries and policy domains. Among 17 FCTC Articles, the greatest progress has been achieved in the implementation of smoke-free laws, health warnings on tobacco packaging, antitobacco mass media campaigns, youth access laws and reporting/exchange of information. On the other hand, progress in all other policy domains has been slow, particularly for the implementation of measures to counter industry interference, regulate tobacco product contents, promote alternative livelihoods and protect the environment and health of tobacco workers.

Only a small number of reporting Parties have taken liability action against the tobacco industry over the last decade. It is encouraging to note that the FCTC Treaty text and guidelines have been explicitly cited by a growing number of countries to support new tobacco control measures. The FCTC has also been successfully used as a legal instrument to defend Parties against industry challenges to tobacco control measures, including plain packaging in Australia, and 80% pictorial warnings and single brand presentation in Uruguay.

Although the FCTC has played an important role in driving global progress in the implementation of tobacco control policies over the last decade, there are ongoing challenges to the effective implementation of the Treaty. First, in order to achieve the WHO global target of a 30% reduction in tobacco use by the year 2025, progress in many policy domains needs to be accelerated. Second, the tobacco industry continues to be the greatest threat to the implementation of the FCTC. In 2018, the WHO Convention Secretariat and the Global Center for Good Governance in Tobacco Control (a WHO FCTC Knowledge Hub on Article 5.3) published reports that identified best practices for effective implementation of FCTC Article 5.3 and its guidelines at the country and global level.207 208 There is an urgent need for Parties to implement these measures to eliminate industry interference with policymaking. Finally, long-term sustainable solutions to strengthen capacity, financial support and resources, and enforcement are required to assist Parties to meet their Treaty obligations.

A growing body of research indicates that tobacco control measures that align with the FCTC and its guidelines are effective. This review found strong international evidence that price and tax increases, comprehensive smoke-free policies, pictorial health warnings, comprehensive TAPS bans and cessation interventions are among the most effective strategies to reduce tobacco consumption and tobacco-related health risks, and encourage quitting. We also found that mass media campaigns and well-enforced measures to restrict youth access to tobacco products are consistently associated with decreased smoking initiation and smoking prevalence, and increased cessation in HICs. These results are consistent with several recent studies based on global data28 209–211 and systematic reviews212–216 on the effect of FCTC policies on tobacco-related outcomes, including improved health, decreased smoking prevalence and consumption, decreased SHS exposure, and increased smoking cessation.

On the other hand, there are still significant research gaps on the impact of FCTC measures in several key policy domains. In the vast majority of countries, the development and implementation of measures to prevent industry interference, regulate tobacco product contents and disclosures, promote economically viable alternatives, protect the environment and health, encourage liability action against the industry, and promote cooperation are still in the early stages. It will be important for future research to evaluate the effectiveness of measures in these areas as they are adopted. Finally, there is a paucity of research that has examined the impact of the FCTC by gender and among disadvantaged groups.

This global review has several limitations. First, our summary of global progress in FCTC implementation is largely based on Parties’ self-reports that are not systematically evaluated for consistency with implemented laws, regulations or national strategies/action plans. Furthermore, FCTC implementation reports do not require Parties to submit information on their use of implementation guidelines.23 Second, we did not analyse whether progress in policy implementation and subsequent public health impact is directly due to the FCTC or other factors. It is likely that changes are generated by the FCTC in combination with other country-specific factors, such as political climate, strength of tobacco control advocacy community, policy compliance and enforcement, and pre-existing legislation prior to FCTC ratification. However, the relative impact of the FCTC will vary by country. For example, a recent analysis of daily smoking prevalence estimates in 195 countries from 1990 to 2015 found that a greater percentage achieved significant annualised rates of decline in smoking prevalence from 1990 to 2005 (before FCTC) than from 2005 and 2015 (after FCTC).2 Moreover, there are non-Parties to the FCTC that have implemented strong national tobacco control policies, such as comprehensive smoke-free laws, large graphic health warnings and high tobacco taxes in Argentina, and antitobacco mass media campaigns and accessible tobacco dependence treatment interventions in the USA.3 Third, given the time constraints for completion of the literature review, we did not conduct a systematic review of all empirical evidence on the effectiveness of FCTC measures. Our literature searches were restricted to four databases, published data and English-language sources. We consulted with seven tobacco control experts to identify any key sources missed by our searches; however, their expertise did not cover all 17 FCTC Articles included in this review. Future systematic reviews are needed to synthesise all available evidence on the impact of FCTC policies on tobacco prevalence and consumption, and other outcomes. Fourth, we did not assign quality ratings to sources on FCTC policy impact to prioritise the selection of sources for the current review. Finally, we did not use standardised criteria to categorise the level of progress in FCTC implementation for the 17 Articles included in this review. However, the overall pattern of our findings on global progress in the implementation of FCTC policies is comparable with the latest results of the WHO Convention Secretariat’s 2016 global progress report on FCTC implementation across 16 Articles,23 as well as the WHO 2017 report on the global implementation of core demand-reduction measures.3

Conclusion

This narrative review summarises evidence on FCTC impact over its first 10 years. The FCTC has served as a powerful tool to initiate, support and advance national, regional and global tobacco control efforts. The effectiveness of core demand-reduction policies is well established, and emerging evidence suggests that strong implementation of these measures can lead to significant reductions in tobacco use.10 28 29 It is now time for Parties to build on achievements and to address gaps in policy implementation and research, especially in LMICs. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognises tobacco control as a critical component to achieve all 17 SDGs. In order to change the current trajectory of the global tobacco epidemic and meet the SDG targets, Parties need to accelerate the implementation of all FCTC provisions, in combination with systematic evaluation of policy effectiveness.

What this paper adds.

This narrative review synthesised evidence on the impact of the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) across 17 substantive Articles over its first 10 years.

This narrative evidence review found that there has been an increase in the implementation of tobacco control legislation since the FCTC came into force, but progress varies across countries and policy domains.

The FCTC is a powerful legal instrument that can be used by countries to support new tobacco control measures and to defend against industry challenges to legislation.

There is strong international evidence that FCTC-compliant measures are effective.

Significant gaps exist for both the implementation and evaluation of measures to counter industry interference (Article 5.3), regulate tobacco product contents (Article 9), promote alternative livelihoods (Article 17), protect the environment and health of tobacco workers (Article 18), and promote cooperation (Article 22).

To achieve the Sustainable Development Goals to strengthen FCTC implementation and reduce premature mortality from non-communicable diseases, Parties need to fulfill their Treaty obligations, implement measures that go beyond the minimum provisions of the Convention and eliminate industry interference.

Acknowledgments

We thank the following tobacco control experts for editing and reviewing the content of the global evidence review that was prepared for the WHO FCTC Impact Assessment Expert Group: Dr Gary J Fooks, Aston University (Article 5.3); Dr Anna B Gilmore, University of Bath (Articles 5.3, 12, 13 and 15); Dr Richard J O’Connor, Roswell Park Cancer Institute (Articles 9 and 10); Rob Cunningham, Canadian Cancer Society (Article 11); Dr Martin Raw, International Centre for Tobacco Cessation and University of Nottingham (Article 14); Dr Jeffrey Drope, American Cancer Society (Article 17); and Dr Natacha Lecours, International Development Research Centre (Article 18). We also thank Jonathan Liberman and Anita George from the McCabe Centre for Law and Cancer; and Patricia Lambert, Monique E Muggli and other colleagues from the International Legal Consortium (ILC) of the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids (CTFK) for their report on WHO FCTC in Legislation and Litigation, which we used as a main evidence source in our review of the implementation and effectiveness of Article 19.

Footnotes

This narrative review did not include FCTC Articles for which impact assessment was not relevant: introduction (Articles 1–3); objective, guiding principles and general obligations (Articles 3–5); institutional arrangements and financial resources (Articles 23–26); settlement of disputes (Article 27); development of the Convention (Articles 28–29); and final provisions (Articles 30–38).

Contributors: JC-H led the writing of the paper and updated literature searches. JC-H, SG and NS conducted literature searches. LC revised the drafts of the paper and reviewed updates to the literature searches. LC, SG, NS and GTF reviewed and revised the draft paper.

Funding: Health Canada (grant number: 4500345764), Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant number: FDN-148477) and Senior Investigator Grant from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research.

Disclaimer: GTF received honorarium from the Secretariat of the WHO FCTC for his work as member of the impact assessment expert group.

Competing interests: GTF has served as an expert witness on behalf of governments in litigation involving the tobacco industry.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. The original release of this article stated incorrectly that the authors were WHO staff members. In fact, the Impact Assessment Expert Group was independent of both the WHO and the FCTC Secretariat in the preparation of its report and of this article.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. GBD 2015 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 79 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1659–724. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31679-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. GBD 2015 Tobacco Collaborators. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease burden in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2017;389:1885–906. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30819-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2017. Monitoring tobacco use and prevention policies. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eriksen M, Mackay J, Schluger N, et al. . The tobacco atlas. 5th edn Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2011. Warning about the dangers of tobacco. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Health Organization. WHO global report: mortality attributable to tobacco. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. World Health Organization. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. 2003http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/42811/1/9241591013.pdf?ua=1

- 9. World Health Organization. The WHO framework convention on tobacco control: an overview. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dubray J, Schwartz R, Chaiton M, et al. . The effect of MPOWER on smoking prevalence. Tob Control 2015;24:540–2. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Puska P. Framework convention on tobacco control: 10 years of the pioneering global health instrument. Eur J Public Health 2016;26:1 10.1093/eurpub/ckv178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shang C, Huang J, Cheng KW, et al. . Global evidence on the association between POS advertising bans and youth smoking participation. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2016;13:306 10.3390/ijerph13030306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Frazer K, Callinan JE, McHugh J, et al. . Legislative smoking bans for reducing harms from secondhand smoke exposure, smoking prevalence and tobacco consumption. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;2:CD005992 10.1002/14651858.CD005992.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bilano V, Gilmour S, Moffiet T, et al. . Global trends and projections for tobacco use, 1990-2025: an analysis of smoking indicators from the WHO comprehensive information systems for tobacco control. Lancet 2015;385:966–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60264-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. What will it take to create a tobacco-free world? Lancet 2015;385:915 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60512-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Decision FCTC/COP6(13) Impact assessment of the WHO FCTC. 2014http://apps.who.int/gb/fctc/PDF/cop6/FCTC_COP6(13)-en.pdf

- 17. WHO Convention Secretariat. Reporting and exchange of information (decision FCTC/COP1(14)). Synthesis of reports on implementation of the WHO framework convention on tobacco control received from parties (before 27 February 2007). Geneva: WHO Convention Secretariat, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18. WHO Convention Secretariat. Reports of the Parties received by the Convention Secretariat and progress made internationally in implementation of the Convention (Decision FCTC/COP1/(14)). 2008http://www.who.int/fctc/reporting/summary_2008_document_cop_3_14.pdf?ua=1

- 19. WHO Convention Secretariat. Summary report on global progress in implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: WHO Convention Secretariat, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 20. WHO Convention Secretariat. Global progress report on the implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: WHO Convention Secretariat, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21. WHO Convention Secretariat. Global progress report on implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: WHO Convention Secretariat, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22. WHO Convention Secretariat. Global progress report on implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: WHO Convention Secretariat, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23. WHO Convention Secretariat. Global progress report on implementation of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Geneva: WHO Convention Secretariat, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24. World Health Organization. Surveillance and monitoring. 2017http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/surveillance/en/

- 25. Hoffman SJ, Tan C. Overview of systematic reviews on the health-related effects of government tobacco control policies. BMC Public Health 2015;15:744 10.1186/s12889-015-2041-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Faber T, Kumar A, Mackenbach JPJ, et al. . Effect of tobacco control policies on perinatal and child health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e420–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Levy DT, Yuan Z, Luo Y, et al. . Seven years of progress in tobacco control: an evaluation of the effect of nations meeting the highest level MPOWER measures between 2007 and 2014. Tob Control 2018;27:50–7. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ngo A, Cheng KW, Chaloupka FJ, et al. . The effect of MPOWER scores on cigarette smoking prevalence and consumption. Prev Med 2017;105S:S10–14. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gravely S, Giovino GA, Craig L, et al. . Implementation of key demand-reduction measures of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and change in smoking prevalence in 126 countries: an association study. Lancet Public Health 2017;2:e166–74. 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30045-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. Impact assessment of the WHO FCTC (Decision FCTC/COP6(13)). Moscow: WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Naslund JA, Aschbrenner KA, Araya R, et al. . Digital technology for treating and preventing mental disorders in low-income and middle-income countries: a narrative review of the literature. Lancet Psychiatry 2017;4:486–500. 10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30096-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Collins JA, Fauser BC. Balancing the strengths of systematic and narrative reviews. Hum Reprod Update 2005;11:103–4. 10.1093/humupd/dmh058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2015: raising taxes on tobacco. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Uang R, Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Accelerated adoption of smoke-free laws after ratification of the world health organization framework convention on tobacco control. Am J Public Health 2016;106:166–71. 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Canadian Cancer Society. Cigarette package health warnings: international status report. 4th edn Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hiilamo H, Crosbie E, Glantz SA. The evolution of health warning labels on cigarette packs: the role of precedents, and tobacco industry strategies to block diffusion. Tob Control 2014;23:e2 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2013: enforcing bans on tobacco advertising, promotion and sponsorship. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hiilamo H, Glantz SA. Implementation of effective cigarette health warning labels among low and middle income countries: state capacity, path-dependency and tobacco industry activity. Soc Sci Med 2015;124:241–5. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.11.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. World Health Organization. WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic, 2009 : implementing smoke-free environments. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 40. ERC Group. World cigarettes 1 and 2: the 2007 survey. 2007.

- 41. Miguel-Baquilod M, Luz S, Quimbo A, et al. . The economics of tobacco and tobacco taxation in the Philippines. 2012https://global.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/global/pdfs/en/Philippines_tobacco_taxes_report_en.pdf

- 42. John R, Pasha HA, Pasha AG, et al. . The economics of tobacco and tobacco taxation in Pakistan. 2013https://tobacconomics.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/PakistanReport_May2014.pdf

- 43. World Health Organization. WHO technical manual on tobacco tax administration. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dorotheo U, Ratanachena S, Ritthiphakdee B, et al. . ASEAN tobacco tax report card: regional comparisons and trends. 5th edn Bangkok, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Department of Finance Canada. The road to balance: creating jobs and opportunities. Economic action plan 2014. 2014http://www.budget.gc.ca/2014/docs/plan/pdf/budget2014-eng.pdf

- 46. Government of New Zealand. Budget economic and fiscal update 2012. 2012http://www.treasury.govt.nz/budget/forecasts/befu2012

- 47. Australian Government Department of Health. Taxation: the history of tobacco excise arrangements in Australia since 1901. 2014http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/tobacco-tax

- 48. Willemsen MC, Nagelhout GE. Country differences and changes in focus of scientific tobacco control publications between 2000 and 2012 in Europe. Eur Addict Res 2016;22:52–8. 10.1159/000381674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Espino R, Assunta M, Kin F. Status of tobacco farming in the ASEAN region. 2013.

- 50. Ministry of Agrarian Development of Brazil. Tobacco growing, family farmers and diversification strategies in Brazil: current prospects and future potential for alternative crops. Technical document for the second section of the Conference of the Parties to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. 2007.

- 51. WHO Convention Secretariat. FCTC implementation database: progress made in implementing Article 18. 2014http://apps.who.int/fctc/implementation/database/article/article-18/indicators/5472/reports

- 52. Muggli ME, Zheng A, Liberman J, et al. . Tracking the relevance of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in legislation and litigation through the online resource, Tobacco Control Laws. Tob Control 2014;23:457–60. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hong MK, Bero LA. How the tobacco industry responded to an influential study of the health effects of secondhand smoke. BMJ 2002;325:1413–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Neuman M, Bitton A, Glantz S. Tobacco industry strategies for influencing European Community tobacco advertising legislation. Lancet 2002;359:1323–30. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08275-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lee S, Ling PM, Glantz SA. The vector of the tobacco epidemic: tobacco industry practices in low and middle-income countries. Cancer Causes Control 2012;23(Suppl 1):117–29. 10.1007/s10552-012-9914-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Smith KE, Savell E, Gilmore AB. What is known about tobacco industry efforts to influence tobacco tax? A systematic review of empirical studies. Tob Control 2013;22:e1 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Savell E, Gilmore AB, Fooks G. How does the tobacco industry attempt to influence marketing regulations? A systematic review. PLoS One 2014;9:e87389 10.1371/journal.pone.0087389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Fooks GJ, Smith J, Lee K, et al. . Controlling corporate influence in health policy making? An assessment of the implementation of article 5.3 of the World Health Organization framework convention on tobacco control. Global Health 2017;13:12 10.1186/s12992-017-0234-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Gilmore AB, Rowell A, Gallus S, et al. . Towards a greater understanding of the illicit tobacco trade in Europe: a review of the PMI funded ’Project Star' report. Tob Control 2014;23:e51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Joossens L, Gilmore AB, Stoklosa M, et al. . Assessment of the European Union’s illicit trade agreements with the four major Transnational Tobacco Companies. Tob Control 2016;25:254–60. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Assunta M. Tobacco industry’s ITGA fights FCTC implementation in the Uruguay negotiations. Tob Control 2012;21:563–8. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Crosbie E, Sosa P, Glantz SA. The importance of continued engagement during the implementation phase of tobacco control policies in a middle-income country: the case of Costa Rica. Tob Control 2017;26:60–8. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Peeters S, Costa H, Stuckler D, et al. . The revision of the 2014 European tobacco products directive: an analysis of the tobacco industry’s attempts to ’break the health silo'. Tob Control 2016;25:108–17. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fooks GJ, Gilmore AB. Corporate philanthropy, political influence, and health policy. PLoS One 2013;8:e80864 10.1371/journal.pone.0080864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Gilmore AB, Fooks G, Drope J, et al. . Exposing and addressing tobacco industry conduct in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2015;385:1029–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60312-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Crosbie E, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry argues domestic trademark laws and international treaties preclude cigarette health warning labels, despite consistent legal advice that the argument is invalid. Tob Control 2014;23:e7 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Lencucha R. Philip Morris versus Uruguay: health governance challenged. Lancet 2010;376:852–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61256-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fooks G, Gilmore AB. International trade law, plain packaging and tobacco industry political activity: the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Tob Control 2014;23:e1 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Evans-Reeves KA, Hatchard JL, Gilmore AB. ’It will harm business and increase illicit trade': an evaluation of the relevance, quality and transparency of evidence submitted by transnational tobacco companies to the UK consultation on standardised packaging 2012. Tob Control 2015;24:e168–77. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ulucanlar S, Fooks GJ, Hatchard JL, et al. . Representation and misrepresentation of scientific evidence in contemporary tobacco regulation: a review of tobacco industry submissions to the UK Government consultation on standardised packaging. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001629 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. World Health Organization. WHO welcomes landmark decision from Australia’s High Court on Tobacco Plain Packaging Act. 2012http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2012/tobacco_packaging/en/

- 72. McCabe Centre for Law & Cancer. Investment tribunal dismisses Philip Morris Asia’s challenge to Australia’s plain packaging. 2015http://untobaccocontrol.org/kh/legal-challenges/investment-tribunal-dismisses-philip-morris-asias-challenge-australias-plain-packaging/

- 73. High Court of Justice. British American Tobacco, Philip Morris International, JT International, Imperial Tobacco v. Secretary of State for Health. Case No: CO/2322/2015, CO/2323/2015, CO/2352/2015, CO/2601/2015, CO/2706/2015. 2016.

- 74. Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization. PAHO/WHO congratulates Uruguay for successfully defending tobacco control policies against tobacco industry challenges. 2016http://www.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=12273%3Apaho-congratulates-uruguay-for-defending-tobacco-control-policies-against-tobacco-industry&Itemid=1926&lang=en

- 75. Torjesen I. Tobacco giant loses legal action over Uruguay’s tobacco packaging rules. BMJ 2016;354:i3850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Court of Justice of the European Union. Press release No 48/16. The New EU directive on tobacco products is valid. 2016https://curia.europa.eu/jcms/upload/docs/application/pdf/2016-05/cp160048en.pdf

- 77. Liberman J. Plainly constitutional: the upholding of plain tobacco packaging by the High Court of Australia. Am J Law Med 2013;39:361–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. McCabe Centre for Law & Cancer. The High Court of Justice decision upholding the UK’s standardized packaging laws: key points for other jurisdictions. 2016http://www.mccabecentre.org/blog/uk-decision.html

- 79. Piné-Abata H, McNeill A, Murray R, et al. . A survey of tobacco dependence treatment services in 121 countries. Addiction 2013;108:1476–84. 10.1111/add.12172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kruse GR, Rigotti NA, Raw M, et al. . Tobacco dependence treatment training programs: an international survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2016;18:1012–8. 10.1093/ntr/ntv142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Makoka D, Appau A, Lencucha R, et al. . Farm-level economics of tobacco production in Malawi. 2016https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305379990_Farm-Level_Economics_of_Tobacco_Production_in_Malawi

- 82. Magati P, Li Q, Drope J, et al. . The economics of tobacco farming in Kenya. Nairobi, Atlanta. 2016.

- 83. Goma F, Drope J, Zulu R, et al. . The economics of tobacco farming in Zambia. Lusaka, Atlanta. 2015https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/economic-and-healthy-policy/economics-tobacco-farming-zambia-presentation-version-december-2015.pdf

- 84. Altman DG, Levine DW, Howard G, et al. . Tobacco farmers and diversification: opportunities and barriers. Tob Control 1996;5:192–8. 10.1136/tc.5.3.192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Warren CW, Erguder T, Lee J, et al. . Effect of policy changes on cigarette sales: the case of Turkey. Eur J Public Health 2012;22:712–6. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Yürekli A, Önder Z, Erk SF, et al. . The economics of tobacco and tobacco taxation in Turkey. 2010http://www.who.int/tobacco/en_tfi_turkey_report_feb2011.pdf

- 87. Waters H, Sáenz de Miera B, Ross H, et al. . The economics of tobacco and tobacco taxation in Mexico. 2010https://global.tobaccofreekids.org/assets/global/pdfs/en/Mexico_tobacco_taxes_report_en.pdf

- 88. Van Walbeek C. Tobacco excise taxation in South Africa. 2003http://www.who.int/tobacco/training/success_stories/en/best_practices_south_africa_taxation.pdf?ua=1

- 89. World Health Organization Western Pacific Region, ITC Project. Smoke-free policies in China: evidence of effectiveness and implications for action. 2015http://itcproject.org/resources/view/2159

- 90. Fong GT, Hyland A, Borland R, et al. . Reductions in tobacco smoke pollution and increases in support for smoke-free public places following the implementation of comprehensive smoke-free workplace legislation in the Republic of Ireland: findings from the ITC Ireland/UK Survey. Tob Control 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii51–iii58. 10.1136/tc.2005.013649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Fong GT, Craig LV, Guignard R, et al. . Evaluating the effectiveness of France’s indoor smoke-free law 1 year and 5 years after implementation: findings from the ITC France Survey. PLoS One 2013;8:e66692 10.1371/journal.pone.0066692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Cooper J, Borland R, Yong HH, et al. . Compliance and support for bans on smoking in licensed venues in Australia: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four-Country Survey. Aust N Z J Public Health 2010;34:379–85. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00570.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Brennan E, Cameron M, Warne C, et al. . Secondhand smoke drift: examining the influence of indoor smoking bans on indoor and outdoor air quality at pubs and bars. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12:271–7. 10.1093/ntr/ntp204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Avila-Tang E, Travers MJ, Navas-Acien A. Promoting smoke-free environments in Latin America: a comparison of methods to assess secondhand smoke exposure. Salud Publica Mex 2010;52(Suppl 2):S138–48. 10.1590/S0036-36342010000800009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Connolly GN, Carpenter CM, Travers MJ, et al. . How smoke-free laws improve air quality: a global study of Irish pubs. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11:600–5. 10.1093/ntr/ntp038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Hyland A, Travers MJ, Dresler C, et al. . A 32-country comparison of tobacco smoke derived particle levels in indoor public places. Tob Control 2008;17:159–65. 10.1136/tc.2007.020479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Goodman PG, Haw S, Kabir Z, et al. . Are there health benefits associated with comprehensive smoke-free laws. Int J Public Health 2009;54:367–78. 10.1007/s00038-009-0089-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Stallings-Smith S, Zeka A, Goodman P, et al. . Reductions in cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory mortality following the national Irish smoking ban: interrupted time-series analysis. PLoS One 2013;8:e62063 10.1371/journal.pone.0062063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Sebrié EM, Sandoya E, Hyland A, et al. . Hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction before and after implementation of a comprehensive smoke-free policy in Uruguay. Tob Control 2013;22:e16–20. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Sebrié EM, Sandoya E, Bianco E, et al. . Hospital admissions for acute myocardial infarction before and after implementation of a comprehensive smoke-free policy in Uruguay: experience through 2010. Tob Control 2014;23:471–2. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Pell JP, Haw S, Cobbe S, et al. . Smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2008;359:482–91. 10.1056/NEJMsa0706740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Tan CE, Glantz SA. Association between smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for cardiac, cerebrovascular, and respiratory diseases: a meta-analysis. Circulation 2012;126:2177–83. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.121301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Been JV, Nurmatov U, van Schayck CP, et al. . The impact of smoke-free legislation on fetal, infant and child health: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002261 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-002261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Fowkes FJ, Stewart MC, Fowkes FG, et al. . Scottish smoke-free legislation and trends in smoking cessation. Addiction 2008;103:1888–95. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02350.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Gravely S, Fong GT, Driezen P, et al. . The impact of the 2009/2010 enhancement of cigarette health warning labels in Uruguay: longitudinal findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Uruguay Survey. Tob Control 2016;25:89–95. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control 2011;20:327–37. 10.1136/tc.2010.037630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Hammond D, Fong GT, McDonald PW, et al. . Impact of the graphic Canadian warning labels on adult smoking behaviour. Tob Control 2003;12:391–5. 10.1136/tc.12.4.391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Hammond D, McDonald PW, Fong GT, et al. . The impact of cigarette warning labels and smoke-free bylaws on smoking cessation: evidence from former smokers. Can J Public Health 2004;95:201–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Hammond D, Reid JL, Driezen P, et al. . Pictorial health warnings on cigarette packs in the United States: an experimental evaluation of the proposed FDA warnings. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:93–102. 10.1093/ntr/nts094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Huang J, Chaloupka FJ, Fong GT. Cigarette graphic warning labels and smoking prevalence in Canada: a critical examination and reformulation of the FDA regulatory impact analysis. Tob Control 2014;23(Suppl 1):i7–12. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Hammond D, Fong GT, McNeill A, et al. . Effectiveness of cigarette warning labels in informing smokers about the risks of smoking: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii19–25. 10.1136/tc.2005.012294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Borland R, Wilson N, Fong GT, et al. . Impact of graphic and text warnings on cigarette packs: findings from four countries over five years. Tob Control 2009;18:358–64. 10.1136/tc.2008.028043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. ITC Project. FCTC Article 11 tobacco warning labels: evidence and recommendations from the ITC Project. 2009http://www.itcproject.org/files/ITC_Tobacco_Labels_Bro_V3.pdf

- 114. Fathelrahman AI, Li L, Borland R, et al. . Stronger pack warnings predict quitting more than weaker ones: finding from the ITC Malaysia and Thailand surveys. Tob Induc Dis 2013;11:20 10.1186/1617-9625-11-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Chiosi JJ, Andes L, Asma S, et al. . Warning about the harms of tobacco use in 22 countries: findings from a cross-sectional household survey. Tob Control 2016;25:393–401. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Miller CL, Hill DJ, Quester PG, et al. . Impact on the Australian quitline of new graphic cigarette pack warnings including the Quitline number. Tob Control 2009;18:235–7. 10.1136/tc.2008.028290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Li J, Grigg M. New Zealand: new graphic warnings encourage registrations with the quitline. Tob Control 2009;18:72 10.1136/tc.2008.027649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Wilson N, Li J, Hoek J, et al. . Long-term benefit of increasing the prominence of a quitline number on cigarette packaging: 3 years of Quitline call data. N Z Med J 2010;123:109–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. British Heart Foundation, ITC Project. Standardised packaging for tobacco products. 2014http://www.itcproject.org/files/ITC_British_Heart_FoundationA4-v8-web-Final-18Dec2014.pdf

- 120. Hammond D. Standardized packaging of tobacco products: evidence review. Prepared on behalf of the Irish Department of Health. 2014http://health.gov.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/2014-Ireland-Plain-Pack-Main-Report-Final-Report-July-26.pdf

- 121. Chantler S. Standardised packaging of tobacco. Report of the independent review undertaken by Sir Cyril Chantler. 2014https://www.kcl.ac.uk/health/10035-TSO-2901853-Chantler-Review-ACCESSIBLE.PDF

- 122. Moodie C, Stead M, Bauld L, et al. . Plain tobacco packaging: a systematic review. 2012http://phrc.lshtm.ac.uk/papers/PHRC_006_Final_Report.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 123. Wakefield M, Coomber K, Zacher M, et al. . Australian adult smokers' responses to plain packaging with larger graphic health warnings 1 year after implementation: results from a national cross-sectional tracking survey. Tob Control 2015;24:ii17–25. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Yong HH, Borland R, Hammond D, et al. . Smokers' reactions to the new larger health warning labels on plain cigarette packs in Australia: findings from the ITC Australia project. Tob Control 2016;25:181–7. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-051979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Dunlop SM, Dobbins T, Young JM, et al. . Impact of Australia’s introduction of tobacco plain packs on adult smokers' pack-related perceptions and responses: results from a continuous tracking survey. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005836 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Durkin S, Brennan E, Coomber K, et al. . Short-term changes in quitting-related cognitions and behaviours after the implementation of plain packaging with larger health warnings: findings from a national cohort study with Australian adult smokers. Tob Control 2015;24:ii26–32. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Young JM, Stacey I, Dobbins TA, et al. . Association between tobacco plain packaging and Quitline calls: a population-based, interrupted time-series analysis. Med J Aust 2014;200:29–32. 10.5694/mja13.11070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Australian Department of Health. Post-implementation review tobacco plain packaging 2016. 2016http://ris.pmc.gov.au/2016/02/26/tobacco-plain-packaging/

- 129. Kmietowicz Z. Australia sees large fall in smoking after introduction of standardised packs. BMJ 2014;349:g4689 10.1136/bmj.g4689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. ITC Project. ITC Uruguay national report. Findings from the Wave 1 to 4 Surveys (2006-2012). 2014http://www.itcproject.org/resources/view/1698

- 131. ITC Project. ITC Canada national report: findings from the Wave 1 to 8 Surveys (2002- 2011). 2013http://www.itcproject.org/resources/view/1533.

- 132. Caixeta R, Sinha D, Khoury R, et al. . Adult awareness of tobacco advertising, promotion, and sponsorship--14 countries. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012;61:365–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Harris F, MacKintosh AM, Anderson S, et al. . Effects of the 2003 advertising/promotion ban in the United Kingdom on awareness of tobacco marketing: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control 2006;15(Suppl 3):iii26–33. 10.1136/tc.2005.013110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Kasza KA, Hyland AJ, Brown A, et al. . The effectiveness of tobacco marketing regulations on reducing smokers' exposure to advertising and promotion: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2011;8:321–40. 10.3390/ijerph8020321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Li L, Yong HH, Borland R, et al. . Reported awareness of tobacco advertising and promotion in China compared to Thailand, Australia and the USA. Tob Control 2009;18:222–7. 10.1136/tc.2008.027037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. McNeill A, Lewis S, Quinn C, et al. . Evaluation of the removal of point-of-sale tobacco displays in Ireland. Tob Control 2011;20:137–43. 10.1136/tc.2010.038141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Saffer H, Chaloupka F. The effect of tobacco advertising bans on tobacco consumption. J Health Econ 2000;19:1117–37. 10.1016/S0167-6296(00)00054-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Blecher E. The impact of tobacco advertising bans on consumption in developing countries. J Health Econ 2008;27:930–42. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Saffer H. Tobacco advertising and promotion Tobacco control in developing countries. Oxford: Oxford University, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 140. National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use: smoking and tobacco control monograph No. 19. NIH Pub. No. 07-6242. 2008https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/19/m19_complete.pdf

- 141. Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res 2009;11:25–35. 10.1093/ntr/ntn002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Spanopoulos D, Britton J, McNeill A, et al. . Tobacco display and brand communication at the point of sale: implications for adolescent smoking behaviour. Tob Control 2014;23:64–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Scheffels J, Lavik R. Out of sight, out of mind? Removal of point-of-sale tobacco displays in Norway. Tob Control 2013;22:e37–42. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. West R, Raw M, McNeill A, et al. . Health-care interventions to promote and assist tobacco cessation: a review of efficacy, effectiveness and affordability for use in national guideline development. Addiction 2015;110:1388–403. 10.1111/add.12998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Carson KV, Verbiest ME, Crone MR, et al. . Training health professionals in smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012:CD000214 10.1002/14651858.CD000214.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Warren CW, Jones NR, Chauvin J, et al. . Tobacco use and cessation counselling: cross-country. Data from the Global Health Professions Student Survey (GHPSS), 2005-7. Tob Control 2008;17:238–47. 10.1136/tc.2007.023895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Cooper J, Borland R, Yong HH. Australian smokers increasingly use help to quit, but number of attempts remains stable: findings from the International Tobacco Control Study 2002-09. Aust N Z J Public Health 2011;35:368–76. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00733.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Kasza KA, Hyland AJ, Borland R, et al. . Effectiveness of stop-smoking medications: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction 2013;108:193–202. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04009.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149. Ossip-Klein DJ, McIntosh S. Quitlines in North America: evidence base and applications. Am J Med Sci 2003;326:201–5. 10.1097/00000441-200310000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150. Stead LF, Hartmann-Boyce J, Perera R, et al. . Telephone counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013:CD002850 10.1002/14651858.CD002850.pub3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151. Anderson CM, Zhu SH. Tobacco quitlines: looking back and looking ahead. Tob Control 2007;16(Suppl 1):i81–6. 10.1136/tc.2007.020701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152. Miller CL, Wakefield M, Roberts L. Uptake and effectiveness of the Australian telephone Quitline service in the context of a mass media campaign. Tob Control 2003;12(Suppl 2):53ii–8. 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153. Abdullah ASM, Lam T-H, Chan SSC, et al. . Which smokers use the smoking cessation Quitline in Hong Kong. and how effective is the Quitline? Tob Control 2004;13:415–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154. Bauld L, Bell K, McCullough L, et al. . The effectiveness of NHS smoking cessation services: a systematic review. J Public Health 2010;32:71–82. 10.1093/pubmed/fdp074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155. Dobbie F, Hiscock R, Leonardi-Bee J, et al. . Evaluating Long-term Outcomes of NHS Stop Smoking Services (ELONS): a prospective cohort study. Health Technol Assess 2015;19:1–156. 10.3310/hta19950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156. Mullen KA, Manuel DG, Hawken SJ, et al. . Effectiveness of a hospital-initiated smoking cessation programme: 2-year health and healthcare outcomes. Tob Control 2017;26:293–9. 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157. Gibson JE, Murray RL, Borland R, et al. . The impact of the United Kingdom’s national smoking cessation strategy on quit attempts and use of cessation services: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res 2010;12(Suppl):S64–71. 10.1093/ntr/ntq119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158. Ferguson J, Bauld L, Chesterman J, et al. . The English smoking treatment services: one-year outcomes. Addiction 2005;100(Suppl 2):59–69. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01028.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159. Judge K, Bauld L, Chesterman J, et al. . The English smoking treatment services: short-term outcomes. Addiction 2005;100(Suppl 2):46–58. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01027.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160. Brose LS, West R, McDermott MS, et al. . What makes for an effective stop-smoking service? Thorax 2011;66:924–6. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2011-200251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161. West R, DiMarino ME, Gitchell J, et al. . Impact of UK policy initiatives on use of medicines to aid smoking cessation. Tob Control 2005;14:166–71. 10.1136/tc.2004.008649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162. Bauer UE, Johnson TM, Hopkins RS, et al. . Changes in youth cigarette use and intentions following implementation of a tobacco control program: findings from the Florida Youth Tobacco Survey, 1998-2000. JAMA 2000;284:723–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163. Niederdeppe J, Farrelly MC, Haviland ML. Confirming "truth": more evidence of a successful tobacco countermarketing campaign in Florida. Am J Public Health 2004;94:255–7. 10.2105/AJPH.94.2.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164. Weiss JW, Cen S, Schuster DV, et al. . Longitudinal effects of pro-tobacco and anti-tobacco messages on adolescent smoking susceptibility. Nicotine Tob Res 2006;8:455–65. 10.1080/14622200600670454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165. Brinn MP, Carson KV, Esterman AJ, et al. . Mass media interventions for preventing smoking in young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:CD001006 10.1002/14651858.CD001006.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166. Flynn BS, Worden JK, Secker-Walker RH, et al. . Mass media and school interventions for cigarette smoking prevention: effects 2 years after completion. Am J Public Health 1994;84:1148–50. 10.2105/AJPH.84.7.1148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167. Farrelly MC, Davis KC, Haviland ML, et al. . Evidence of a dose-response relationship between "truth" antismoking ads and youth smoking prevalence. Am J Public Health 2005;95:425–31. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168. Wakefield M, Chaloupka F. Effectiveness of comprehensive tobacco control programmes in reducing teenage smoking in the USA. Tob Control 2000;9:177–86. 10.1136/tc.9.2.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169. Goldman LK, Glantz SA. Evaluation of antismoking advertising campaigns. JAMA 1998;279:772–7. 10.1001/jama.279.10.772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170. Siegel M, Biener L. The impact of an antismoking media campaign on progression to established smoking: results of a longitudinal youth study. Am J Public Health 2000;90:380–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171. Emery S, Wakefield MA, Terry-McElrath Y, et al. . Televised state-sponsored antitobacco advertising and youth smoking beliefs and behavior in the United States, 1999-2000. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2005;159:639 10.1001/archpedi.159.7.639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172. Sly DF, Heald GR, Ray S. The Florida "truth" anti-tobacco media evaluation: design, first year results, and implications for planning future state media evaluations. Tob Control 2001;10:9–15. 10.1136/tc.10.1.9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173. Farrelly MC, Healton CG, Davis KC, et al. . Getting to the truth: evaluating national tobacco countermarketing campaigns. Am J Public Health 2002;92:901–7. 10.2105/AJPH.92.6.901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174. Popham WJ, Potter LD, Bal DG, et al. . Do anti-smoking media campaigns help smokers quit? Public Health Rep 1993;108:510–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175. White V, Tan N, Wakefield M, et al. . Do adult focused anti-smoking campaigns have an impact on adolescents? The case of the Australian National Tobacco Campaign. Tob Control 2003;12(Suppl 2):23ii–9. 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_2.ii23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176. Huang P, Alo C, Satterwhite D, et al. . Usual sources of cigarettes for middle and high school students--Texas, 1998-1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2002;51:900–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 177. Levinson AH, Mickiewicz T. Reducing underage cigarette sales in an isolated community: the effect on adolescent cigarette supplies. Prev Med 2007;45:447–53. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 178. Tutt D, Bauer L, Difranza J. Restricting the retail supply of tobacco to minors. J Public Health Policy 2009;30:68–82. 10.1057/jphp.2008.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]