Abstract

This paper outlines the recommendations from the Association of Colon & Rectal Surgeons of India (ACRSI) practice guidelines for the management of haemorrhoids—2016. It includes diagnosis and management of haemorrhoids including dietary, non-surgical, and surgical techniques. These guidelines are intended for the use of general practitioners, general surgeons, colorectal surgeons, and gastrointestinal surgeons in India.

Keywords: Haemorrhoids, Haemorrhoidectomy, Consensus, Flavonoids, Electrosurgery, Anal canal, Haemorrhoids practice guidelines 2016

Introduction and Methodology

Haemorrhoidal disease is one of the most common anorectal conditions encountered in daily practice by general practitioners, general surgeons, and gastrointestinal surgeons in India. It has been projected that about 50% of the population would have haemorrhoids at some point in their life probably by the time they reach the age 50, and approximately 5% population suffer from haemorrhoids at any given point of time [1, 2]. Taking into account the devastating nature of the disease and high prevalence in India, the evidence-based practice appears essential in the management of haemorrhoids. Present practice parameters aim at developing evidence-based recommendations for the management of haemorrhoids in Indian perspectives.

This practice guideline for the management of haemorrhoids, framed by the Association of Colon & Rectal Surgeons of India (ACRSI) has been developed by experts from across the country with immense experience in managing patients with haemorrhoids. Each section was reviewed by an individual expert in the committee, which was later presented and discussed; and a consensus statement was arrived at by the entire committee. A modified GRADE system was used to derive quality of evidence as 1 (high-quality evidence from consistent results of well-performed randomised trials), 2 (moderate-quality evidence from randomised trials), 3 (low-quality evidence from observational studies, opinions gathered from respected authorities), or 4 (practice point). The strength of recommendations was categorised as either A (“RECOMMENDED”, strong recommendation) or B (“SUGGESTED”, weak recommendation) [3].

Summary of Recommendations

Clinical Evaluation and Diagnosis

Patient history and physical examination are the essential components in the diagnosis of haemorrhoidal disease. Bleeding per rectum, prolapse (something coming out per rectum), perianal swelling, and itching are the common symptoms of haemorrhoids. Pain occurs in cases with complicated haemorrhoids. Symptoms like feeling of incomplete evacuation, change in bowel habits, and weight loss need to be further evaluated to rule out other pathologies such as anal and rectal carcinomas, anal condylomata, and inflammatory bowel disease. A diagnosis is made using proctoscopy and sigmoidoscopy. Further, a full colonoscopy is recommended in selected patients with suspicious symptoms as above and in those with rectal bleeding, occult gastrointestinal bleeding, iron-deficiency anaemia, positive faecal occult blood test, and age ≥50 years and not having a complete colon examination within the past 10 years. (Grade A, Evidence Level 3) [2, 4–7]

The consensus committee also proposed a new classification of haemorrhoids as presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

A new proposed classification of haemorrhoids

| Grade | Characteristics |

| I | Remaining inside the anal canal |

| II | Protrude during defecation and reduce spontaneously |

| III | Need further manual reposition |

| IV | Piles that remain prolapsed outside and external haemorrhoids |

| Each of the above primary grades of haemorrhoids is categorised further, depending on number of piles, and presence of circumferential piles or thrombosis, by the suffix as below | |

| a | Single pile mass |

| b | Two piles but <50% circumference |

| c | Circumferential piles occupying more than half circumference of the anal canal |

| d | Thrombosed or gangrenous piles (complicated) |

Management of Haemorrhoids

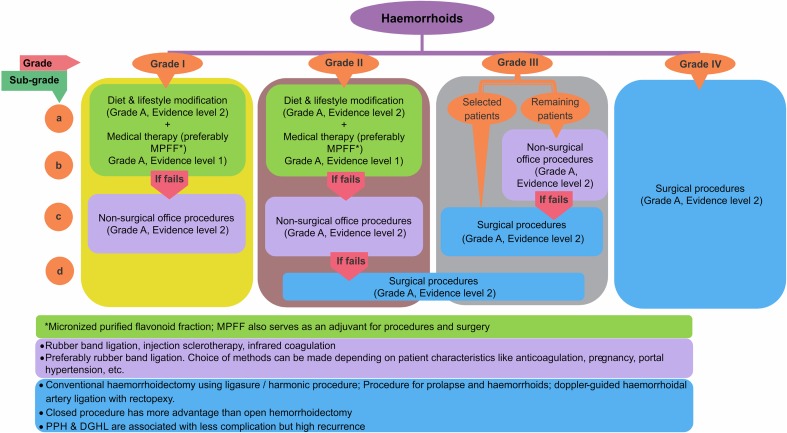

See Fig. 1 for a general approach for the management of haemorrhoids.

Fig. 1.

Haemorrhoid management algorithm

Dietary and Lifestyle Modifications

Haemorrhoidal patients should be recommended to follow a dietary modification involving increased fibre intake with adequate fluid as a first-line treatment. (Grade A, Evidence Level 2) [8, 9]

If constipation is a predominant factor, it should be treated carefully using laxatives like polyethylene glycol, lactulose, and bulking agents. (Grade A, Evidence Level 4)

Medical Management

Medical management by micronised purified flavonoid fraction (MPFF) is recommended as a first-line treatment for grade I–II (a–c) and selected/minor grade III (a–c) haemorrhoids. Acutely bleeding haemorrhoids can be effectively treated by MPFF. In an acute haemorrhoidal attack, MPFF 1000 mg can be prescribed at a dose of three tablets daily for 4 days followed by two tablets daily for 3 days. Further, a maintenance dose of MPFF 1000 mg is preferred once daily for a minimum period of 2 months or more at physician’s discretion. (Grade A, Evidence Level 1) [10, 11]

MPFF also serves as an effective adjuvant to surgery and other procedures. Other existing veno-active drugs like calcium dobesilate, heparan sulphate, Euphorbia prostrata, and Ginkgo biloba have a low level of evidence in the management of haemorrhoids. Calcium dobesilate has been associated with an increased risk of agranulocytosis. (Grade B, Evidence Level 3) [12–17]

The long-term use of topical products, particularly, preparations containing steroid should be avoided due to their detrimental effects. (Grade B, Evidence Level 4)

Non-surgical Office Procedures

Rubber band ligation, injection sclerotherapy, and infrared coagulation can all be used in the treatment of grade I–II and selective grade III haemorrhoids. The success rates are highest with rubber band ligation albeit with a higher complication rate. (Grade A, Evidence Level 2) [18, 19]

Surgical Management of Haemorrhoids

Haemorrhoidectomy

Haemorrhoidectomy is a suitable option for the treatment of grade III–IV haemorrhoids; however, it may be associated with postoperative complications. The closed procedure has more advantages in terms of postoperative pain and bleeding than an open procedure. Advanced techniques like ligasure, harmonic scalpel, and mono- or bipolar modes of electrosurgery could be helpful in overcoming some of the disadvantages of conventional haemorrhoidectomy. (Grade A, Evidence Level 2) [20–22]

Stapled Haemorrhoidopexy

Stapled haemorrhoidopexy is recommended in the treatment of grade III–IV (a–c) haemorrhoids. Stapled haemorrhoidopexy compared to conventional haemorrhoidectomy is more effective in pain control and wound healing and reduces hospital stay and time for return to work. The usage of newer stapling devices may overcome the complications of stapled haemorrhoidopexy. (Grade A, Evidence Level 2) [23]

Doppler-Guided Haemorrhoidal Artery Ligation

Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation (DGHAL)/transanal haemorrhoidal dearterialisation (THD) is recommended in the treatment of grade II–IV haemorrhoids. Although recurrence of grade III and IV haemorrhoids may be a limiting factor, a combination of current techniques like anopexy/mucopexy with DGHAL could address this limitation and broaden the applicability to the grade III and IV haemorrhoids. (Grade A, Evidence Level 2) [24, 25]

Haemorrhoids in Special Situation

Patients on Anticoagulants

Treatment should be based on the grades of haemorrhoids with the cautious management of anticoagulation that does not cause cardiac compromise. Injection sclerotherapy is preferable over rubber band ligation due to the risk of postoperative bleeding complications. (Grade A, Evidence Level 3) [26–29]

Patients Infected with HIV

Conservative treatment should be the first-line approach for the management of symptomatic haemorrhoid patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). If conservative management fails, surgical procedures should be offered with proper management of CD4 counts and prophylactic antibiotics. (Grade A, Evidence Level 3) [30–32]

Haemorrhoids in Pregnancy

All pregnant women with symptomatic haemorrhoids should be managed by a conservative approach, including diet and lifestyle modifications (intake of fibre rich diet, high liquid intake, constipation cessation, personal cleanliness, and lying on the left side to relieve pain and other symptoms) and medical therapy. (Grade A, Evidence Level 4)

Medical therapy with MPFF is safe and effective in the management of haemorrhoids in pregnant women (usage is not advised during the first trimester in the absence of evidence). In the antenatal period, maintenance treatment with MPFF 1000 mg once daily significantly reduces both the frequency and duration of relapses of symptoms of acute haemorrhoids. (Grade A, Evidence Level 3) [33]

Surgical or non-surgical procedures may be advised only in cases with failure of conservative management. Surgical procedure should be reserved for strangulated or thrombosed haemorrhoids and performed under local anaesthesia. (Grade A, Evidence Level 4)

Portal Hypertension and Haemorrhoids

Conservative approach should be tried in all patients with portal hypertension. Differentiation between haemorrhoids and rectal varices should be done in portal hypertensive patients with active rectal bleeding. There are conflicting reports about the use of rubber band ligation in advanced cirrhosis with portal hypertension. Stapled haemorrhoidopexy is a good option for the portal hypertensive haemorrhoids patients, and haemorrhoidectomy should be reserved for the patients who are refractory to other approaches. (Grade A, Evidence Level 4)

Haemorrhoids in Children

Dietary lifestyle modifications, proper toilet training, and medical management are the first-line options for management of haemorrhoids in children. Non-surgical office procedures may be reserved if conservative management fails. (Grade A, Evidence Level 4)

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interests

All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lohsiriwat V (2012) Hemorrhoids: from basic pathophysiology to clinical management. World J Gastroenterol 18(17):2009–2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Mounsey AL, Halladay J, Sadiq TS. Hemorrhoids. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(2):204–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cappell MS. Reducing the incidence and mortality of colon cancer: mass screening and colonoscopic polypectomy. Gastroenterol Clin N Am. 2008;37(1):129–160. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Andrews KS, Brooks D, Bond J, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(5):1570–1595. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Winawer S, Fletcher R, Rex D, Bond J, Burt R, Ferrucci J, et al. Colorectal cancer screening and surveillance: clinical guidelines and rationale-update based on new evidence. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(2):544–560. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rivadeneira DE, Steele SR, Ternent C, Chalasani S, Buie WD, Rafferty JL (2011) Practice parameters for the management of hemorrhoids (revised 2010). Dis Colon rectum 54(9):1059–1064 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Alonso-Coello P, Mills E, Heels-Ansdell D, Lopez-Yarto M, Zhou Q, Johanson JF, et al. Fiber for the treatment of hemorrhoids complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(1):181–188. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso-Coello P, Guyatt G, Heels-Ansdell D, Johanson JF, Lopez-Yarto M, Mills E, et al. Laxatives for the treatment of hemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;4:Cd004649. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004649.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alonso-Coello P, Zhou Q, Martinez-Zapata MJ, Mills E, Heels-Ansdell D, Johanson JF, et al. Meta-analysis of flavonoids for the treatment of haemorrhoids. Br J Surg. 2006;93(8):909–920. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perera N, Liolitsa D, Iype S, Croxford A, Yassin M, Lang P, et al. Phlebotonics for haemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:Cd004322. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004322.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mentes BB, Gorgul A, Tatlicioglu E, Ayoglu F, Unal S (2001) Efficacy of calcium dobesilate in treating acute attacks of hemorrhoidal disease. Dis Colon rectum 44(10):1489–1495 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Gupta PJ. The efficacy of Euphorbia prostrata in early grades of symptomatic hemorrhoids—a pilot study. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2011;15(2):199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Cecco L. Effects of administration of 50 mg heparan sulfate tablets to patients with varicose dilatation of the hemorrhoid plexus (hemorrhoids) Minerva Ginecol. 1992;44(11):599–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sumboonnanonda K, Lertsithichai P. Clinical study of the Ginko biloba–troxerutin–heptaminol Hce in the treatment of acute hemorrhoidal attacks. J Med Assoc Thail. 2004;87(2):137–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtis BR. Drug-induced immune neutropenia/agranulocytosis. Immunohematology. 2014;30(2):95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allain H, Ramelet AA, Polard E, Bentue-Ferrer D. Safety of calcium dobesilate in chronic venous disease, diabetic retinopathy and haemorrhoids. Drug Saf. 2004;27(9):649–660. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200427090-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacRae HM, McLeod RS (1995) Comparison of hemorrhoidal treatment modalities. A meta-analysis. Dis Colon rectum 38(7):687–694 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Shanmugam V, Hakeem A, Campbell, KL, Rabindranath, KS, Steele, RJ, Thaha, MA et al. (2005) Rubber band ligation versus excisional haemorrhoidectomy for haemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD005034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Bhatti MI, Sajid MS, Baig MK. Milligan-Morgan (open) versus Ferguson haemorrhoidectomy (closed): a systematic review and meta-analysis of published randomized, controlled trials. World J Surg. 2016;40(6):1509–1519. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3419-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu L, Chen H, Lin G, Ge Q. Ligasure versus Ferguson hemorrhoidectomy in the treatment of hemorrhoids: a meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015;25(2):106–110. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0000000000000136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nienhuijs S, de Hingh I. Conventional versus LigaSure hemorrhoidectomy for patients with symptomatic hemorrhoids. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;1:Cd006761. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006761.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JS, Vashist YK, Thieltges S, Zehler O, Gawad KA, Yekebas EF, et al. Stapled hemorrhoidopexy versus Milligan-Morgan hemorrhoidectomy in circumferential third-degree hemorrhoids: long-term results of a randomized controlled trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17(7):1292–1298. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giordano P, Overton J, Madeddu F, Zaman S, Gravante G (2009) Transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization: a systematic review. Dis Colon rectum 52(9):1665–1671 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Denoya PI, Fakhoury M, Chang K, Fakhoury J, Bergamaschi R. Dearterialization with mucopexy versus haemorrhoidectomy for grade III or IV haemorrhoids: short-term results of a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Color Dis. 2013;15(10):1281–1288. doi: 10.1111/codi.12303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Atallah S, Maharaja GK, Martin-Perez B, Burke JP, Albert MR, Larach SW. Transanal hemorrhoidal dearterialization (THD): a safe procedure for the anticoagulated patient? Tech Coloproctol. 2016;20(7):461–466. doi: 10.1007/s10151-016-1481-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cavazzoni E, Bugiantella W, Graziosi L, Silvia Franceschini M, Cantarella F, Rosati E, et al. Emergency transanal haemorrhoidal Doppler guided dearterialization for acute and persistent haemorrhoidal bleeding. Color Dis. 2013;15(2):e89–e92. doi: 10.1111/codi.12053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pigot F, Juguet F, Bouchard D, Castinel A. Do we have to stop anticoagulant and platelet-inhibitor treatments during proctological surgery? Color Dis. 2012;14(12):1516–1520. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2012.03063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pigot F, Juguet F, Bouchard D, Castinel A, Vove JP. Prospective survey of secondary bleeding following anorectal surgery in a consecutive series of 1, 269 patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2011;35(1):41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2010.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore BA, Fleshner PR (2001) Rubber band ligation for hemorrhoidal disease can be safely performed in select HIV-positive patients. Dis Colon rectum 44(8):1079–1082 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Scaglia M, Delaini GG, Destefano I, Hulten L (2001) Injection treatment of hemorrhoids in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Dis Colon rectum 44(3):401–404 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Morandi E, Merlini D, Salvaggio A, Foschi D, Trabucchi E (1999) Prospective study of healing time after hemorrhoidectomy: influence of HIV infection, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, and anal wound infection. Dis Colon rectum 42(9):1140–1144 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Buckshee K, Takkar D, Aggarwal N. Micronized flavonoid therapy in internal hemorrhoids of pregnancy. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1997;57(2):145–151. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(97)02889-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]