Abstract

A 42-year-old woman presented to our hospital with weeks of worsening pain around her lower ribs. Preceding this, she was managed in primary care with anti-inflammatory drugs and physiotherapy for presumed costochondritis. Assessment in accident and emergency suggested a tender right upper quadrant with fever and neutrophilia. A surgical review of the patient was requested to assess for cholecystitis or delayed pancreatitis. On direct questioning, the patient's back pain was the predominating symptom with no neurological deficit. To assess for delayed pancreatitis, CT imaging was obtained, demonstrating unremarkable intra-abdominal organs. There was also the incidental finding of thickened prevertebral soft tissues anterior to T9 and T10 vertebrae, with vertebral endplate irregularity locally. Subsequent MRI demonstrated typical appearances of infective spondylodiscitis at this level. The patient made a good recovery with intravenous antimicrobials. This case highlights how vertebrodiscitis can present insidiously and unexpectedly, manifesting as abdominal pain.

Background

The pressure of accident and emergency care can force clinicians to focus only on the most likely and readily diagnosed conditions. Back pain is a very common condition, and differentiating acute and significant pathology from chronic pathology can be challenging. As demonstrated in this patient, the pain was worsening over weeks, a timescale not compatible with chronic disease and when associated with fever it should not be taken lightly.

Case presentation

A 42-year-old woman presented to our accident and emergency department, via ambulance, with fevers and excruciating lower thoracic pain. These symptoms had developed on a background of 6 weeks of back pain that was exacerbated by movement. She reported ever worsening ‘spasms of pain’ scoring 10/10 on an analogue pain scale. She did not experience nausea or vomiting; her stool and urine were normal.

Her observations at presentation were a pulse rate of 83 bpm, blood pressure 123/67 mm Hg, respiratory rate 18 bpm, peripheral oxygen saturation 99%, temperature 38.4°C and blood glucose 4.0 mmol/L.

Her medical history was limited to seasonal asthma not requiring regular inhaled therapy and two caesarean sections. She was taking the combined contraceptive pill and had allergies to penicillin, causing rash and erythromycin, to which she was not certain of the reaction, but no anaphylaxis. There was no family or travel history of relevance, and she lived with her partner and four children.

When examining her, the emergency medical team identified right upper quadrant tenderness with a positive Murphy's sign, no renal angle tenderness and no peritonism. An immediate surgical referral was made to assess for cholecystitis or pancreatitis. Careful questioning revealed that this pain was radiating in a band-like distribution from the thoracic spine around the flanks to the umbilicus.

Investigations

We screened for sepsis with blood tests and cultures, urinalysis and an erect chest X-ray. These revealed elevated markers for acute inflammation and infection, with normal liver and renal function (shown below). The chest X-ray and urinalysis were normal.

Haematological tests: haemoglobin 127 g/L, white cell count 15.3×109/L, platelet count 485×109/L, neutrophil count 12.3×109/L, leucocyte count 2.0×109/L, haematocrit 0.402, mean cell volume 83.8 fL, International Normalised Ratio 1.0.

Biochemical tests (serum): Total protein 64 g/L, albumin 29 g/L, alanine transferase 12 U/L, alkaline phosphatase 84 U/L, total bilirubin 11 µmol/L, total globulins 35 g/L, sodium 138 mmol/L, potassium 4.4 mmol/L, urea 4.2 mmol/L, creatinine 61 µmol/L, amylase 65 U/L, C reactive protein 103 mg/L.

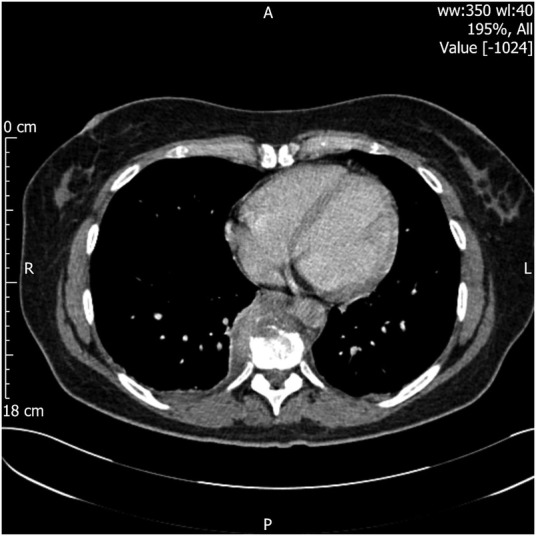

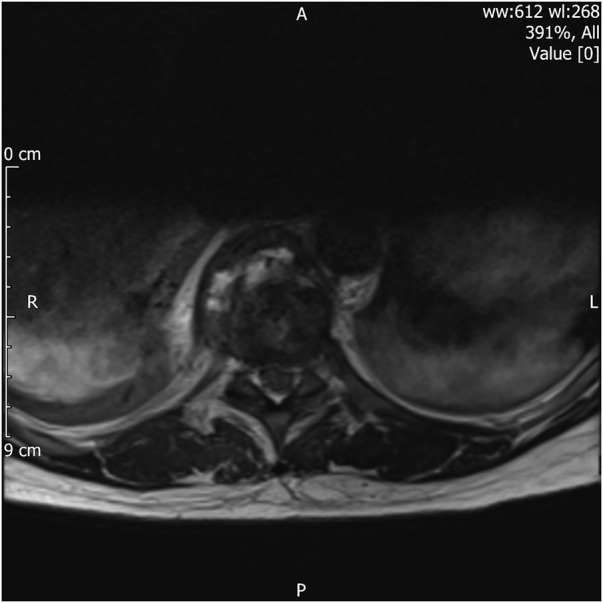

Continuing to investigate our differential diagnosis, we next obtained CT images of the abdomen and pelvis. At the very top of the region imaged in this protocol were the vertebral bodies of T9 and T10 demonstrating prevertebral soft tissue thickening, and T9/10 vertebral endplate irregularity (figure 1), a seemingly incidental finding that was ultimately the key to the crucial diagnosis. Subsequent MRI confirmed that the prevertebral mass on CT corresponded to a paraspinal collection secondary to T9/10 vertebrodiscitis (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

CT of the abdomen/pelvis with contrast: prevertebral low attenuation material and bony irregularity at the T9/10 anterior disc endplate margin is suggestive of a prespinal inflammatory process. This is at the very edge of the field of view and is not well characterised. The differential includes neoplasm on this limited coverage. No definite acute abdominal changes identified.

Figure 2.

MRI of the spine, whole: sagittal STIR lower thoracic levels, axial T2 at T9/10 level—there is abnormal signal in the T9 and T10 vertebrae. There is destruction and erosion of the anterior 1/3 of the disc endplates at T9/T10 level. High signal is noted anteriorly under the anterior longitudinal ligament and in the right paravertebral region, in keeping with a paraspinal inflammatory mass. STIR, short τ inversion recovery image.

Figure 3.

MRI of the spine, whole: sagittal STIR lower thoracic levels, axial T2 at T9/10 level—there is abnormal signal in the T9 and T10 vertebrae. There is destruction and erosion of the anterior 1/3 of the disc endplates at T9/T10 level. High signal is noted anteriorly under the anterior longitudinal ligament and in the right paravertebral region, in keeping with a paraspinal inflammatory mass. STIR, short τ inversion recovery image.

Differential diagnosis

The relatively long duration of the history, especially the pain, coupled with biochemical signs of inflammation despite an unremarkable examination, meant there was very little to guide us as to the source of inflammation. The most readily investigable condition and important to exclude was a delayed presentation of pancreatitis. We also considered peptic or duodenal ulceration as other possibilities. The clinical examination did not fit with renal calculi, nor did it fit with costochondritis, due to the constancy of the pain and the bilateral symptoms, respectively. The biochemical picture dissuaded us from biliary pathology. Bone infections sat very low in our differential in the absence of bony tenderness and neurological signs.

Treatment

In view of the patient's drug allergy history—urticarial rash with penicillin V and a more vague illness with erythromycin—advice from microbiology was sought. The patient was initially treated for 1 week with meropenem and vancomycin. A good clinical response was achieved and treatment in the outpatient setting was considered. Initial trial of clindamycin was not tolerated and she was discharged after 10 days in hospital to receive intravenous ceftriaxone via a peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) line and oral fusidic acid for 6 weeks in the community. She received a further 6 weeks of oral clindamycin and oral fusidic acid after the intravenous course had been completed.

Blood cultures taken at presentation and the day following admission came back negative, with no growth after 5 days’ incubation. Treatment was empirical, with the most likely organism being Staphylococcus aureus, given the patient's age and lack of underlying risk factors. Biopsy was not performed, as intravenous antibiotic therapy was started immediately after diagnosis of spondylodiscitis. Clinical and biochemical improvement was made with antibiotic therapy, making the risk of an invasive procedure unnecessary.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient suffered no neurological compromise while an inpatient. An MRI of the spine was repeated 6 weeks after the original imaging, which showed persistent abnormal signal intensity at T9–10 level, in keeping with spondylodiscitis but no other abnormalities. Further MRI at 11 weeks after presentation showed that there had been partial regression in the spondylodiscitis. The patient was monitored as an outpatient in orthopaedic clinic with regular review of her symptoms, signs, inflammatory markers and imaging. Her inflammatory markers improved, and white cell count and C reactive protein were both within normal ranges at 4 weeks after discharge. She was last seen in clinic at 20 weeks after initial presentation, at which point she had completed 6 weeks of intravenous and 6 weeks of oral antibiotic therapy. Her symptoms had vastly improved with no neurological or orthopaedic injury, blood tests were entirely normal and imaging showed improvement. She was therefore discharged from clinic.

Discussion

Presentation to the acute surgical service with cases such as the one we have described has in the past led to surgical exploration.1 Fortunately, in current practice, cross-sectional imaging has meant that this happens far more infrequently by allowing the confirmation of surgical diagnosis without operation, or, as in our case, the simultaneous exclusion of our differential diagnoses and inclusion of the correct diagnosis.

Diagnosis of this rare condition with very common and non-specific symptoms—pain and fever—remains difficult.2 We are therefore fortunate to have ready access to high-quality diagnostic imaging and recognise that we are still challenged to make best use of it.

Learning points.

Abdominal pain remains an incredibly non-specific clinical sign.

Discitis can present without neurological signs.

Cross-sectional imaging provides a wealth of diagnostic information, but its value is greatest when the whole image is interpreted rather than used to exclude individual diagnoses.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Richard Hughes for his advice on images for the report.

Footnotes

Contributors: ML drafted and revised the case report. AA contributed to the draft and revised the case report. LP revised and updated the case report, and collected the images.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Sullivan CR, Symmonds RE. Disk infections and abdominal pain. JAMA 1964;188:655–8. doi:10.1001/jama.1964.03060330035009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gouliouris T, Aliyu SH, Brown NM. Spondylodiscitis: update on diagnosis and management. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010;65(Suppl 3):iii11–24. doi:10.1093/jac/dkq303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]