Abstract

Infective endocarditis is an uncommon manifestation of infection with Histoplasma capsulatum. The diagnosis is frequently missed, and outcomes historically have been poor. We present 14 cases of Histoplasma endocarditis seen in the last decade at medical centers throughout the United States. All patients were men, and 10 of the 14 had an infected prosthetic aortic valve. One patient had an infected left atrial myxoma. Symptoms were present a median of 7 weeks before the diagnosis was established. Blood cultures yielded H. capsulatum in only 6 (43%) patients. Histoplasma antigen was present in urine and/or serum in all but 3 of the patients and provided the first clue to the diagnosis of histoplasmosis for several patients. Antibody testing was positive for H. capsulatum in 6 of 8 patients in whom the test was performed.

Eleven patients underwent surgery for valve replacement or myxoma removal. Large, friable vegetations were noted at surgery in most patients, confirming the preoperative transesophageal echocardiography findings. Histopathologic examination of valve tissue and the myxoma revealed granulomatous inflammation and large numbers of organisms in most specimens. Four of the excised valves and the atrial myxoma showed a mixture of both yeast and hyphal forms on histopathology.

A lipid formulation of amphotericin B, administered for a median of 29 days, was the initial therapy in 11 of the 14 patients. This was followed by oral itraconazole therapy, in all but 2 patients. The length of itraconazole suppressive therapy ranged from 11 months to lifelong administration. Three patients (21%) died within 3 months of the date of diagnosis. All 3 deaths were in patients who had received either no or minimal (1 day and 1 week) amphotericin B.

INTRODUCTION

Infection with Histoplasma capsulatum is a rare cause of endocarditis. A review of cases of fungal endocarditis reported from 1965 to 1995 identified H. capsulatum as the etiologic agent in 15 of 270 (6%) cases,11 and a subsequent review encompassing the years 1995 to 2000 noted that only 2 of 152 (1%) cases were due to H. capsulatum.23 Focusing specifically on fungal prosthetic valve endocarditis, histoplasmosis assumes a greater role; Boland et al7 reported that 3 of the 21 cases (14%) seen at the Mayo Clinic from 1970 to 2008 were caused by H. capsulatum. A total of only 43 cases of Histoplasma endocarditis, most reported as single cases, have been noted in the 60 years from 1943 to 2003.3

The diagnosis of Histoplasma endocarditis is challenging because the automated blood culture systems that are commonly used do not favor the growth of this organism. Many cases have been identified only at autopsy.3 The diagnostic approach to culture-negative endocarditis has improved over the last decade, and optimal management of fungal endocarditis in regard to antifungal treatment and surgical intervention has evolved. To our knowledge, there has been no contemporary multicenter case series focusing on endocarditis caused by H. capsulatum. In the current study, we sought to describe the clinical manifestations, the use of newer diagnostic tools for the diagnosis of Histoplasma endocarditis, the approach to treatment, and the outcomes of patients who had Histoplasma endocarditis.

METHODS

A convenience sample of cases of Histoplasma endocarditis seen from January 2003 to December 2012 was identified from multiple sites across the United States through laboratory records at MiraVista Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN. To be included in the study, patients needed to meet the case definition as follows: 1) endocarditis with a vegetation or a cardiac mass documented by echocardiography or at surgery; 2) no other pathogen isolated; 3) at least 1 of the following: a positive Histoplasma antigen test later verified by histopathology or culture, histopathologic evidence of budding yeasts with or without hyphal forms in heart valve tissue, a culture yielding H. capsulatum from blood or another sterile site, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positive for H. capsulatum from heart valve tissue.

A standardized data collection form was used to collect clinical data on patients who met the case definition. Participating clinicians provided protected health information according to the regulations of their local oversight authority and/or approval through their local Institutional Review Board. Simple statistical analysis using means, medians, and standard deviations was utilized.

SELECTED CASE REPORTS

Case 1 (Table 1, Patient 12)

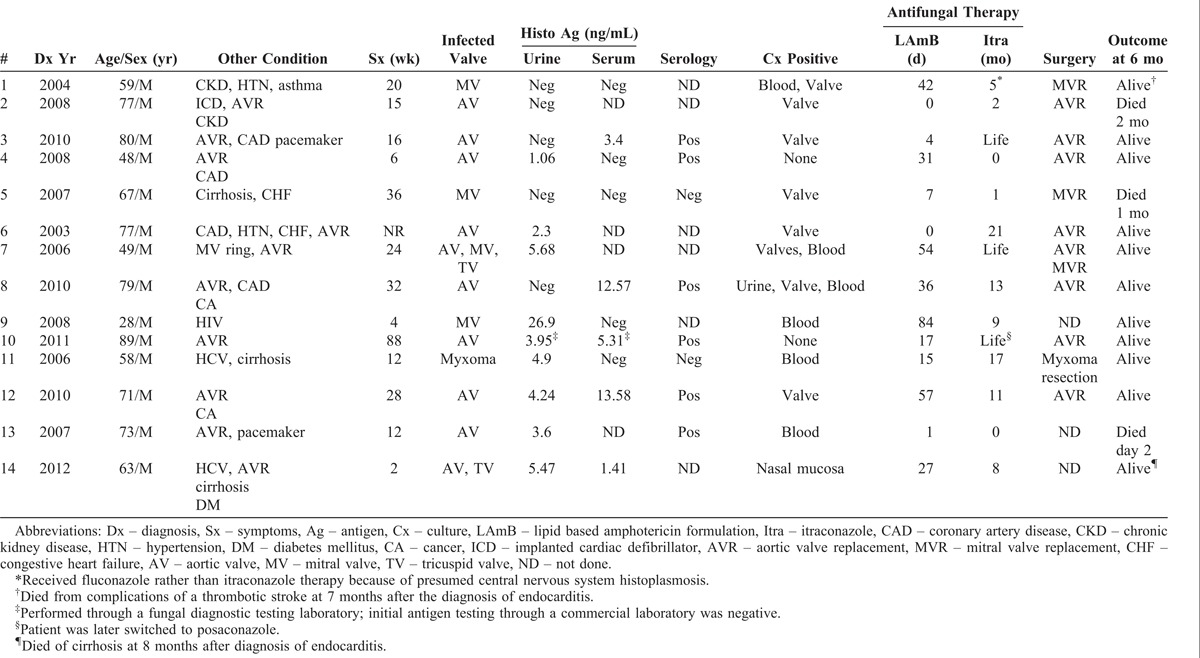

TABLE 1.

Clinical Characteristics, Diagnostic Testing, Treatment, and Outcomes of 14 Patients With Histoplasma Endocarditis

A 71-year-old man who had undergone aortic valve replacement with a porcine allograft in 2004 for aortic stenosis and who had recently been treated for prostate cancer, presented with a 6-month history of malaise and mild dyspnea and the recent onset of confusion, lower extremity weakness, and syncope. He lived in Acapulco, Mexico, during the winter and resided in Michigan during the summer.

He was admitted to hospital in October 2010 with fever and mental status changes. Examination revealed a temperature of 101.8 °F, pulse 114/min, and blood pressure 111/66 mm Hg. A harsh 3/6 systolic ejection murmur was audible throughout the precordium and radiated to the carotids. There were no peripheral stigmata of endocarditis. There was mild left-greater-than-right weakness of the lower extremities. He was alert and oriented to self and place but not to time. He was unable to provide the details of much of his medical history and had deficits in short term memory.

White blood cell (WBC) count was 8800/μL, hemoglobin (Hb) 13.6 g/dL, platelet count 111,000/μL, creatinine 1.1 mg/dL. An MRI of the brain showed no changes and a lumbar puncture revealed no abnormalities. A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) revealed a severely thickened bioprosthetic aortic valve and severe aortic stenosis. A transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) identified a large amount of soft-tissue density material encompassing the bioprosthetic valve leaflets with mobile components consistent with vegetations. Splenic infarcts consistent with emboli were identified on abdominal ultrasound.

Multiple sets of blood cultures processed by the BacTAlert system and the lysis-centrifugation (Isolator tube) system were obtained prior to the initiation of antibiotic therapy, and all yielded no growth. A Histoplasma antigen enzyme immunoassay (EIA) test was positive in urine (4.26 ng/mL) and serum (13.58 ng/mL). The complement fixation (CF) assay for antibodies against H. capsulatum was negative, but the immunodiffusion (ID) assay showed antibodies to both H and M antigens of H. capsulatum.

Therapy with liposomal amphotericin B, 5 mg/kg per day, was initiated, and 10 days later the patient underwent replacement of his aortic valve and ascending aorta with a homograft as an inclusion root. Histopathology of the resected aortic valve revealed both yeast and hyphal forms (Figure 1). PCR assay performed at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) was positive for H. capsulatum, and culture yielded growth of H. capsulatum. After 6 weeks of treatment with liposomal amphotericin B, therapy was changed to oral itraconazole for a total treatment course of 12 months. The serum and urine antigen assays became negative after 6 months of treatment. Three years later, in August 2013, he felt well and had no evidence of recurrent infection.

FIGURE 1.

Histopathology of resected prosthetic aortic valve from Case 1 (Patient 12 in Table 1). Grocott methenamine silver stain demonstrating both yeast forms and hyphal elements.

Comment: This patient had a prolonged illness with many negative blood cultures. The presence of H. capsulatum antigen and antibodies in concert with the TEE showing vegetations on the bioprosthetic valve led to the diagnosis of Histoplasma endocarditis. A noteworthy feature of this case was the predominance of hyphae, rather than small oval yeasts, noted on the excised prosthetic valve, which led to the request for the PCR assay to verify the identity of the organism before the culture yielded H. capsulatum.

Case 2 (Table 1, Patient 11)

A 58-year-old man who had hepatitis C-related cirrhosis complicated by ascites was admitted to hospital in March 2006 with a 3-month history of weakness, lower extremity edema, nausea, vomiting, loose stools, urinary incontinence, a 15-pound weight loss, and a 1-month history of fevers. On admission, he was febrile to 101.8 °F, blood pressure was 63/43 mm Hg, and pulse was 90/min. He appeared cachectic; jaundice, ascites, and lower extremity edema were noted. No heart murmur was heard.

The WBC was 3600/μL, Hb 11.0 g/dL, platelets 66,000/μL, creatinine 2.7 mg/dL, and bilirubin 2.9 mg/dL. A TEE demonstrated mild mitral valve regurgitation and a mildly dilated left atrium that contained a 7.8 cm multilobulated, frondlike, mobile mass that prolapsed across the mitral valve (Figure 2). An Isolator blood culture obtained at admission yielded H. capsulatum 2 weeks later. Repeated Isolator blood cultures taken 7 days after admission also yielded H. capsulatum. The initial Histoplasma urinary antigen was 4.90 ng/mL, and the serum Histoplasma antigen was negative. Antibody studies (CF and ID) were negative.

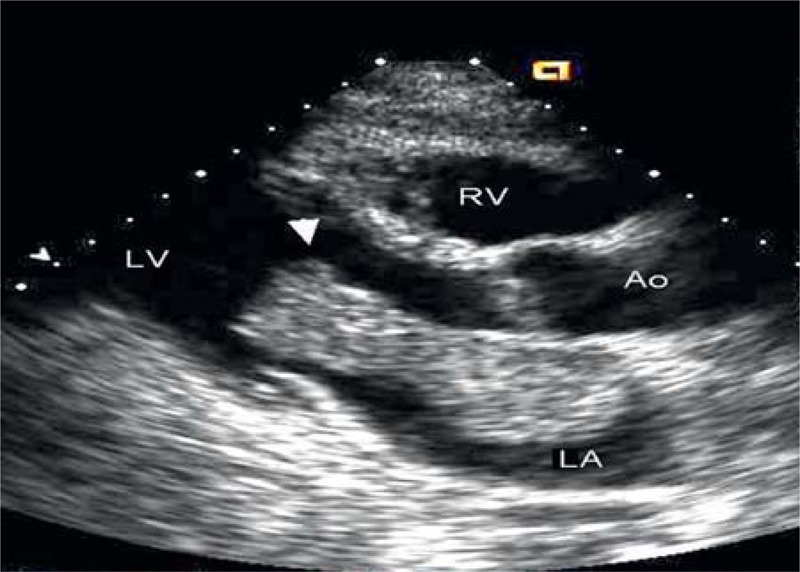

FIGURE 2.

Transesophageal echocardiogram of Case 2 (Patient 11 in Table 1) demonstrating a large mass (arrow) extending from the left atrium (LA), to the left ventricle (LV) across the mitral valve.

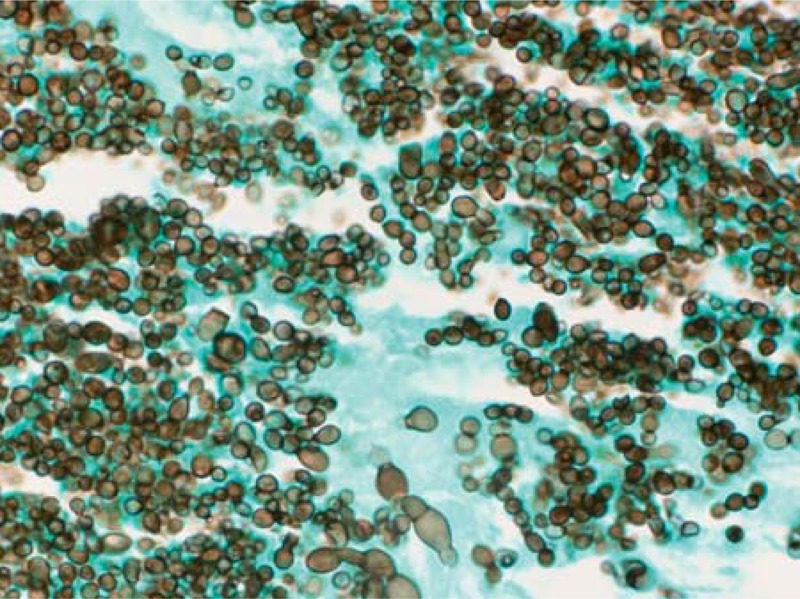

Resection of the atrial mass was performed because of near-complete obliteration of the left ventricular cavity with prolapse of the mass across the mitral valve and hypotension requiring vasopressors (Figure 3). Microscopic examination of the mass revealed myxomatous tissue with a surface encased by thrombus and dense colonies of yeast that were morphologically consistent with H. capsulatum (Figure 4). Rare hyphal elements were also observed.

FIGURE 3.

Resected atrial myxoma from Case 2 (Patient 11 in Table 1).

FIGURE 4.

Histopathology of resected myxoma from Case 2 (Patient 11 in Table 1). Grocott methenamine silver stain demonstrating both typical yeast forms and enlarged atypical yeast structures.

He was treated with amphotericin B lipid complex, 5 mg/kg per day, for 15 days. Step-down treatment with oral itraconazole was initiated. He received a total duration of itraconazole of 17 months, with dosages varying between 200 mg once or twice daily to 200 mg thrice daily to achieve therapeutic serum concentrations. The patient was well without recurrent infection in December 2011, 4.5 years after treatment was stopped.

Comment: This patient is unique in that he is only the second reported case of an atrial myxoma infected with H. capsulatum. The myxoma was very large and obstructed flow through the mitral valve. Most of the mass showed yeast forms typical of H. capsulatum, but hyphae were also noted. This patient, in contrast to most others in this series, had positive blood cultures for H. capsulatum.

RESULTS

Demographics

Fourteen patients who had proven infective endocarditis caused by H. capsulatum were identified in the 10 years from 2003 to 2012. The mean age was 65.6 ± 16.2 years (range, 28–89 yr). All of the patients were men. Patients were seen in many areas of the country, including Indiana, Michigan, Tennessee, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Idaho, and California. One patient from Idaho was a native of Guatemala, but the other patient from Idaho and the patient from California had no known exposures to areas considered to be endemic for H. capsulatum. Two patients were briefly reported previously, 1 in a table listing cases of fungal prosthetic valve endocarditis7 and the other in a manuscript detailing the use of DNA sequencing to identify fungi in tissues.22

Clinical Characteristics

All patients had multiple comorbidities, including, valvular heart disease, prosthetic cardiac valves, coronary artery disease, cirrhosis, solid tumors, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease (Table 1). Not surprisingly, the most common underlying illness was valvular heart disease, and 10 patients had a prosthetic cardiac valve. Symptoms were present a median of 7 weeks (range, 2–88 wk) before the diagnosis of endocarditis was established. Patient 10, who had a prolonged course of 88 weeks, may or may not have had endocarditis the entire time. It is possible that he had relapsing disseminated histoplasmosis that later seeded onto the prosthetic valve. Ten patients (71%) had prosthetic aortic valve endocarditis, 3 had native mitral valve endocarditis, and 1 had an infected atrial myxoma. Of the 10 patients who had aortic prosthetic valve endocarditis, 1 also had endocarditis of the native tricuspid valve, another had endocarditis involving the native tricuspid valve and the mitral valve, which previously had been repaired with ring placement, and a third had an infected cardiac defibrillator wire. Four patients (Patients 9, 10, 13, 14) were thought to have disseminated histoplasmosis in addition to endocarditis.

Presenting symptoms included fever in 13, fatigue and weight loss in 5 each, heart failure (shortness of breath, edema) in 5, and neurologic symptoms (altered mental status, stroke) in 4. All but Patient 1 had documented fever. Emboli to major vessels, including those to the cerebrum, the spleen, and the extremities, occurred in 4 patients (Patients 1, 4, 12, 13), all of whom had emboli to multiple organs.

Physical examination documented a murmur in 10 patients, signs of congestive heart failure (rales and/or edema) in 5, splenomegaly in 3, and cutaneous stigmata of endocarditis in only 1 patient. One patient had a nasal ulceration that later yielded H. capsulatum in culture.

Cardiac Echocardiography Studies

All 14 patients had TEE findings reported. Eleven patients had vegetations that were noted to be more than 1 cm in size or were described as “large,” and the vegetations specifically were noted to be mobile in 10 patients. Patient 3 had vegetations described along the defibrillator wire as well as on the aortic valve prosthesis, and Patient 11 had a large left atrial myxoma that prolapsed across the mitral valve. Vegetations were not described for Patients 10 and 13. However, at valve replacement surgery for severe aortic insufficiency in Patient 10, the original bioprosthetic valve was destroyed and histopathologic examination revealed abundant fungi. An autopsy in Patient 13 revealed vegetations on the sewing ring of the aortic prosthesis, and these were shown to contain H. capsulatum.

Laboratory Studies

The mean initial WBC was 5157/μL ± 2640/μL. Anemia was present in all but 1 patient (mean Hb, 11 ± 1.9 g/dL), and platelet counts ranged from 34,000–434,000/μL (mean 139,000 ± 107,000/μL). Transaminases were elevated more than twice the upper limit of normal in only 2 patients, 1 of whom had disseminated histoplasmosis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (Patient 9). Six patients had mildly increased alkaline phosphatase levels (154–256 u/mL), and bilirubin was elevated in 4 patients (2.0–3.6 mg/dL).

Antigen and Antibody Testing

All patients had Histoplasma urine antigen testing performed; results of the initial test were positive in 9 and negative in 5. One patient had a negative urine antigen test performed at a commercial laboratory, but a subsequent test at a laboratory that specialized in fungal testing was positive, and this patient is counted among the 9 having an initial positive test. Two of the 5 patients who had a negative antigen test in urine had antigen detected in serum, 2 were negative in serum as well as urine, and 1 did not have an antigen test performed on serum. The mean value of the initial positive urine antigen test was 6.5 ± 7.8 ng/mL (range, 1.1–26.9 ng/mL).

Ten patients had Histoplasma antigen testing performed on serum; 5 were positive and 5 were negative. One patient had a negative serum antigen test performed at a commercial laboratory, but a subsequent test at a laboratory that specialized in fungal testing was positive and this patient is among the 5 counted as having an initial positive test. Positive values on the first sample tested ranged from 1.4–13.6 ng/mL. Two of the 5 positive serum antigen tests were in patients who had negative results for Histoplasma antigen in urine. All 5 patients seen from 2009 to 2012 had serum antigen testing performed, and in all, the test was positive. Of the 5 patients who had negative serum antigen tests, all were seen prior to 2009 when a change in the assay increased its sensitivity. Stored serum samples from 2 of these 5 (Patients 1, 4) were retested using ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) pretreatment of the serum, and both were positive by this more sensitive assay. All patients, with the exception of Patients 1, 2, and 5, had either a positive serum or a positive urine test for Histoplasma antigen; 3 patients had positive results from both sites, and 2 had negative results from both sites.

Of the 11 patients who initially had a positive urine or serum antigen detected, 8 had urine and/or serum antigen tests followed longitudinally over time. The number of follow-up tests varied considerably from patient to patient ranging from 2 follow-up tests over 2 months to 19 tests over almost 3 years; the frequency of testing depended partly on the clinical course and the number of follow-up visits. With the exception of Patient 10 who appeared to have relapsing infection over a prolonged period, the 7 other patients who had follow-up antigen testing performed had a negative test documented between 1 and 9 months after initial diagnosis.

Of the 8 patients in whom antibody assays for H. capsulatum were performed, 6 had positive results. Three patients had both complement fixation and immunodiffusion antibodies identified, 1 had only complement fixation antibodies, and 2 had antibodies positive only by immunodiffusion.

Microbiology

All 14 patients had blood cultures performed, and most had multiple blood samples cultured. Blood cultures were performed by automated systems (BacTAlert and BACTEC) and/or the lysis centrifugation (Isolator tube) system. In 6 patients, blood was cultured using both systems, in 6 patients an automated system only, and in 2 patients an Isolator tube system only. Of the 8 patients in whom cultures were performed using an Isolator tube system, only 2 were positive for H. capsulatum, including 1 who had multiple negative cultures using an automated system. Of the 12 patients in whom cultures were performed using an automated system, 4 had positive cultures for H. capsulatum. For 1 of these 4, a blood culture bottle was found to contain H. capsulatum only after it was subcultured onto fungal medium 1 month after it was initially inoculated with blood (Patient 7).

Eleven patients underwent surgical excision of the infected valve or atrial mass. The tissue yielded H. capsulatum by culture techniques in 8 patients. Three patients, 2 of whom also had a positive culture from the valve, had evidence for H. capsulatum by 18sRNA PCR performed on valve tissue. In another patient, in whom valve cultures were not performed, in situ hybridization showed H. capsulatum on valve tissue obtained at autopsy. Other sites that yielded H. capsulatum in culture included urine in 1 patient and a nasal lesion in another.

Histopathology

Histopathologic findings were reported for 9 heart valves and the atrial myxoma excised at surgery, a brachial arterial embolus that was removed, and from autopsy specimens in Patient 13. Two patients (Patients 9, 14) who had disseminated infection also showed histopathologic evidence of histoplasmosis in a nasal biopsy and a bone marrow biopsy, respectively, and Patient 13 had poorly formed granulomas in many different organs at autopsy. The heart valves were described as showing necrotizing granulomas, granulomatous inflammation, or granulation tissue with fibrinous debris. Patient 10 had sheets of fungi, but no granulomatous inflammation was seen. Fungi were noted in all cardiac samples. Four heart valves and the atrial myxoma had both yeast and hyphal elements noted, and the other 5 heart valves were described as having yeast forms only. Among the latter, some valves were reported to show 2–4 μm oval-shaped budding yeasts typical of H. capsulatum, but others demonstrated a mixture of larger yeast forms as well as more typical small yeasts.

Therapy and Outcomes

Eleven patients underwent surgical intervention. Aortic valve replacement was performed in 7, mitral valve replacement in 2, both aortic and mitral valve replacement in 1, and 1 patient underwent resection of an infected atrial myxoma. Patients 13 and 14 were deemed too ill to undergo surgery, and it was electively decided to not replace the mitral valve in Patient 9. With the exception of Patients 2, 6, and 10, all patients were treated with a lipid formulation of amphotericin B as initial therapy. The family of Patient 2 did not allow therapy with amphotericin B, and the reason for not using amphotericin B was not stated for Patient 6. Patient 10 had an unusually long course and ultimately did receive therapy with a lipid formulation of amphotericin B after he experienced a relapse of histoplasmosis following azole therapy. The median duration of therapy with lipid formulation amphotericin B was 29 days (range 1–84 days). Two patients, both of whom died, received only 1 and 7 days of amphotericin B, respectively. Renal insufficiency limited the duration of amphotericin B therapy in 5 patients.

Twelve of the 14 patients received azole therapy. One of the 2 patients who was not treated with an azole died after only 1 day of therapy with liposomal amphotericin B (Patient 13); the other (Patient 4), was treated with liposomal amphotericin B for 31 days, the valve was replaced, and he survived without subsequent azole therapy. Itraconazole was prescribed for 11 of the 12 azole-treated patients; Patient 1 received fluconazole because he had central nervous system emboli, and Patient 10 was transitioned from itraconazole to lifelong posaconazole therapy. The length of azole therapy in those who survived ranged from 11 months to lifelong therapy.

Three patients (21%) died within 6 months from the date of diagnosis of Histoplasma endocarditis. Death was definitely thought to be due to histoplasmosis in Patients 5 and 13, and was due to postoperative complications following valve replacement in Patient 2. One of the patients who died was not treated with amphotericin B (Patient 2), and 1 received only 1 day of amphotericin B therapy before he died (Patient 13). Patient 5 died at 1 month having had only 1 week of liposomal amphotericin B therapy and valve replacement. Two other patients died; Patient 1 died at 7 months of complications from a post-operative stroke and Patient 14 died of liver failure at 8 months after the diagnosis of Histoplasma endocarditis was established. Only 1 patient was known to have survived without undergoing valve replacement (Patient 9), but unfortunately, he was lost to follow at 10 months after the diagnosis was established.

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter study, we found that men who have prosthetic heart valves seemed to be at particularly high risk for this unusual manifestation of histoplasmosis. Detection of H. capsulatum cell wall polysaccharide in urine or serum proved useful in the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, and TEE was valuable in defining the presence of endocarditis and atrial myxoma in 1 case. Treatment strategies that combined valve replacement surgery with lipid formulation amphotericin B, followed by step-down treatment with itraconazole, appeared to be most effective.

Endocarditis caused by H. capsulatum is uncommon in comparison with that caused by Candida and Aspergillus species.11,23 A comprehensive literature review of endocarditis caused specifically by H. capsulatum documented 43 cases that occurred between 1943 and 2003.3 Our series adds another 14 cases that were seen in the decade since 2003 and shows the evolution of the diagnosis and treatment of this infection since the last major review.

In cases reported from 1943 to 2003, 36 of 43 (84%) involved native valves; in contrast, in the current series, 10 of 14 (71%) cases were on prosthetic valves. Almost all cases reported since 1995 describe patients in whom infection was on a prosthetic valve.3,7,13,17,18,21 The review of cases from 1943 to 2003 found that most (85%) occurred in men, and this was similar in our series, in which all cases were men.

Clinical findings were not suggestive of histoplasmosis in many patients, as noted in earlier reports.3 Several patients described weeks to months of fever and fatigue before the diagnosis was established. Biopsy of other organs in the few patients who had clear-cut disseminated histoplasmosis led to the correct diagnosis, but 10 of the 14 patients had endocarditis without widespread disseminated infection. Once a TEE was performed and revealed mobile vegetations, the diagnosis focused on culture-negative endocarditis, and antigen testing proved most useful.

One patient in our series had an infected atrial myxoma, a very rare manifestation of endocarditis. Two large reviews of fungal endocarditis described no cases associated with a myxoma.11,23 To our knowledge, only 1 prior case caused by H. capsulatum has been reported.25 In that patient, as in the patient reported here, both yeast and hyphal forms were noted in the myxomatous tissue. In the previously reported patient, who also had disseminated histoplasmosis, a bone marrow biopsy showed only small oval-shaped budding yeasts typical for H. capsulatum and no hyphal forms, in contrast to abundant hyphae seen in the myxoma and associated thrombus.25

Of interest are the unusual morphologic forms demonstrated in infected valve tissue. In 5 cases, hyphae were seen in addition to yeasts. In several valve specimens, there were large, thick-walled structures that could be derived from yeasts or perhaps represent abortive sporulation; they also could be large irregular hyphae cut in cross section. The ability of H. capsulatum to produce hyphae when causing an intravascular infection has been commented upon before6,15,16,28; Hutton et al16 noted that 9 of 27 cases of Histoplasma endocarditis described prior to 1986 showed hyphae in valvular tissue or arterial emboli. Recent cases of Histoplasma endocarditis, in addition to those in this report, also describe hyphae in valve tissue and emboli.13,17 Hyphal formation in vivo has been described only rarely in other tissues outside the vascular compartment.5,27

Interestingly, hyphal forms also were reported in blood cultures taken from an AIDS patient who died from overwhelming disseminated histoplasmosis; in that case, growth had occurred within 4–5 days in Bactec aerobic bottles, and both yeasts and hyphae were seen on the calcofluor stain of the broth.26 The stimulus to produce hyphae in vivo is not known. This phenomenon has been uncommonly noted in another endemic mycosis, coccidioidomycosis, in which hyphae, as well as spherules, have been described in 1 case of prosthetic valve endocarditis and in several cases of ventriculo-peritoneal shunt infections.24,32 A major diagnostic issue is that the organisms easily could be mistaken for Candida or Aspergillus species, which are more common causes of endocarditis than H. capsulatum and which manifest hyphal forms in tissues.

The diagnosis of Histoplasma endocarditis has evolved over the last 2 decades with increasing use of antigen detection in urine and serum, improved blood culture techniques, and the availability of PCR and in situ hybridization assays.4,10,14,19,22,29,31 In the review of 43 cases prior to 2003, it was noted that detection of antibody to H. capsulatum was helpful in 20 patients and culture of various sites was helpful in 20 patients; most patients had both serology and culture performed, but only 7 patients had a positive blood culture.3 No cases were reported in which antigen testing had been performed. Seventeen cases were diagnosed only at autopsy.

In contrast, in the present series, the most useful early diagnostic test was detection of H. capsulatum antigen. It was the initial clue to a possible diagnosis of Histoplasma endocarditis in several patients. Antigen detection has been most useful in patients who have disseminated histoplasmosis, in which the sensitivity of the assay approaches 90%.14 We found the assays in serum and urine to be complimentary to each other. Discordance was noted between serum and urine antigen detection in 4 patients. Two had antigen detected in urine but not serum, and 2 had antigen detected in serum but not urine. Thus, both tests should be performed to increase their usefulness for the diagnosis of Histoplasma endocarditis.

The Histoplasma antigen test is not performed with identical reagents and techniques in all laboratories. There have been reports of discrepancies in antigen test results between different laboratories, and this likely relates to differences in reagents used for the different assays.9,10,12,20 Additionally, over time, the EIA assay in serum has been improved with the use of EDTA and heat pretreatment of the serum to 104 °C prior to testing. This method presumably improves antigen detection by dissociating immune complexes thereby improving the sensitivity of the test.29 In 2 patients in this series, the antigen testing performed on serum was negative at the time the patient was initially evaluated, but was positive when the same serum that had been frozen and stored was retested several years later using EDTA and heat pretreatment.

Molecular identification of fungi is an increasingly powerful tool.2 For 1 patient it provided the only proof that the atypical fungal forms seen on the involved aortic valve were H. capsulatum. PCR targeting ribosomal RNA sequences specific for H. capsulatum has proved to be extremely useful4,19,22; in situ hybridization of tissues can also be used to identify the organism.2 In 1 reported case, a diagnosis of histoplasmosis was made on a tissue sample by using a commercially available DNA probe (GEN-PROBE, Inc, San Diego, CA) that is designed to confirm that a mold grown in culture is H. capsulatum.8

The TEE has become invaluable in documenting valvular abnormalities and has assumed an important role in establishing the diagnosis of infectious endocarditis.1,30 In the series of Histoplasma endocarditis cases from 1943 to 2003, echocardiography results were reported in only a single case. In contrast, all of our patients had at least 1 TEE performed. The large sizes of the vegetations seen in most were suggestive of fungal endocarditis.11,23 However, in several patients, the TEE revealed only abnormal soft-tissue surrounding a prosthetic valve, or severe valve dysfunction without a mobile vegetation.

At the present time, there is no standard approach to the management of Histoplasma endocarditis suggested by the American Heart Association or the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).1,33 As a general rule, most clinicians in this series initiated therapy with a lipid formulation of amphotericin B. However, the duration of amphotericin B therapy varied and in some patients was limited by nephrotoxicity. Patients who were treated with a lipid formulation of amphotericin B received a median of 29 days (range, 1–84 d) of treatment, followed by step-down therapy to an azole, most commonly itraconazole, for durations that varied from 11 months to lifelong. This strategy is similar to the recommendations for the treatment of central nervous system histoplasmosis in the IDSA guidelines.33 Most patients with Histoplasma endocarditis reported contemporaneously have been managed with a similar approach.3,13,17,18,21

Prior to the introduction of amphotericin B in the mid-1950 s, all patients who had Histoplasma endocarditis died. Even in the ensuing 2 decades after amphotericin B was available, only 50% of 18 reported patients were treated, and the overall mortality remained high at 72%.3 Of the total of 21 patients who were reported between 1958 and 2003 and who were treated with amphotericin B, with or without surgery, only 5 (24%) died.3 In our series of 14 cases seen since 2003, 3 patients (21%) had died by the 6-month follow-up, but 2 of the 3 were either not treated with amphotericin B or received only 1 day of therapy before death.

Although histoplasmosis is an uncommon cause of endocarditis, patients who have culture-negative endocarditis should nevertheless be evaluated for infection with this organism. This is especially true of patients who live in or have traveled to areas that are endemic for H. capsulatum. Our data suggest that men who have prosthetic heart valves and who present with culture negative endocarditis should be considered at particularly high risk of having Histoplasma endocarditis. The diagnosis is often suggested first by positive urine or serum Histoplasma antigen tests. Once a diagnosis of Histoplasma endocarditis is made, especially when a prosthetic valve is infected, strong consideration should be given for surgical intervention. If surgery is performed, histopathologic examination of the resected valve tissue using special stains and culture and/or PCR assay for H. capsulatum should be performed. Initial therapy with liposomal amphotericin B, 5 mg/kg per day, with a goal of completing 4–6 weeks of treatment, is suggested. Subsequent treatment with itraconazole for a period of at least 12 months should be considered. Monitoring Histoplasma antigen tests during the course of therapy seems reasonable to assess the response to therapy. For some patients, lifelong suppressive treatment with an azole may be necessary. With early diagnosis and effective intervention, outcomes associated with Histoplasma endocarditis should be favorable.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: CF = complement fixation, EDTA = ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, EIA = enzyme linked immunoassay, Hb = hemoglobin, ID = immunodiffusion, IDSA = Infectious Diseases Society of America, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, TEE = transesophageal echocardiogram, TTE = transthoracic echocardiogram, WBC = white blood cells.

Financial support and conflicts of interest: L.J.W. is President and Director of MiraVista Diagnostics. The other authors have no funding or conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer Fowler ASVG, et al. Infective endocarditis: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke, and Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, American Heart Association: endorsed by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Circulation. 2005;111:e394–e434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balajee SA, Sigler L, Brandt ME. DNA and the classical way: identification of medically important molds in the 21st century. Med Mycol. 2007;45:475–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhatti S, Vilenski L, Tight R. Smego RA Jr. Histoplasma endocarditis: clinical and mycologic features and outcomes. J Infect. 2005;51:2–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bialek R, Ernst F, Dietz K, et al. Comparison of staining methods and a nested PCR assay to detect Histoplasma capsulatum in tissue sections. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:597–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Binford CH. Histoplasmosis: tissue reactions and morphologic variations of fungus. Am J Clin Pathol. 1955;25:25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blair TP, Waugh RA, Pollack M, et al. Histoplasma capsulatum endocarditis. Am Heart J. 1980;9:783–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boland JM, Chung HH, Robberts FJL, et al. Fungal prosthetic valve endocarditis: Mayo Clinic experience with a clinicopathological analysis. Mycoses. 2011;54:354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chemaly RF, Tomford JW, Hall GS, et al. Rapid diagnosis of Histoplasma capsulatum endocarditis using the AccuProbe on an excised valve. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2640–2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cloud JL, Bauman SK, Pelfrey JM, et al. Biased report on the IMMY ALPHA Histoplasma antigen enzyme immunoassay for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:1389–1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connolly PA, Durkin MM, LeMonte AM, et al. Detection of Histoplasma antigen by quantitative enzyme immunoassay. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:1587–1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis ME, Al-Abdely H, Sandridge A, et al. Fungal endocarditis: evidence in the world literature, 1965–1995. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez BL, Figueroa JI, Hamilton AJ, et al. Detection of the 70-kilodalton Histoplasma capsulatum antigen in serum of histoplasmosis patients: correlation between antigenemia and therapy during follow-up. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:675–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gotoff R, Franceschelli J, Prichard J, et al. A 78-year-old man with a 4-month history of fever, fatigue, and weight loss (Photo Quiz). J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hage CA, Ribes JA, Wengenack NL, et al. A multicenter evaluation of tests for diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:448–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haust MD, Wloder GK, Parker JO. Histoplasma endocarditis. Am J Med. 1962;32:460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutton JP, Durham JB, Miller DP, et al. Hyphal forms of Histoplasma capsulatum. A common manifestation of intravascular infection. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1985;109:330–332. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isotalo PA, Chan KL, Rubens F, et al. Prosthetic valve fungal endocarditis due to histoplasmosis. Can J Cardiol. 2001;17:297–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jinno S, Gripshover BM, Lemonovich TL, et al. Histoplasma capsulatum prosthetic valve endocarditis with negative fungal blood cultures and negative Histoplasma antigen assay in an immunocompetent patient. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:4664–4666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koepsell SA, Hinrichs SV, Iwen PC. Applying a real-time PCR assay for Histoplasma capsulatum to clinically relevant formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded human tissue. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3395–3397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.LeMonte A, Egan L, Connolly P, et al. Evaluation of the IMMY ALPHA Histoplasma antigen enzyme immunoassay for diagnosis of histoplasmosis marked by antigenuria. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14:802–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lorchirachonkul N, Foongladda S, Ruangchira-Urai R, et al. Prosthetic valve endocarditis caused by Histoplasma capsulatum: the first case report in Thailand. J Med Assoc Thai. 2013;96Suppl 2:S262–S265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moncada PA, Budvytiene I, Ho DY, et al. Utility of DNA sequencing for direct identification of invasive fungi from fresh and formalin-fixed specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;140:203–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pierrotti LC, Baddour LM. Fungal endocarditis, 1995–2000. Chest. 2002;122:302–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reuss CS, Hall MC, Blair JE, et al. Endocarditis caused by Coccidioides species. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:1451–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rogers EW, Weyman AE, Noble RJ, et al. Left atrial myoxma infected with Histoplasma capsulatum. Am J Med. 1978;64:683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salimnia H, Brown P, Lephart P, et al. Hyphal and yeast forms of Histoplasma capsulatum growing within 5 days in an automated bacterial blood culture system. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:2833–2834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwarz J. Histoplasmosis. NY: Praeger; 1981: 12–31. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Svirbely JR, Ayers LW, Buesching WJ. Filamentous Histoplasma capsulatum endocarditis involving mitral and aortic porcine bioprostheses. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1985;109:273–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Swartzentruber S, LeMonte A, Witt J, et al. Improved detection of Histoplasma antigenemia following dissociation of immune complexes. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2009;16:320–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009). Eur Heart J. et al. 2009;30:2369–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vetter E, Torgerson C, Feuker A, et al. Comparison of the BACTEC MYCO/F lytic bottle to the isolator tube, BACTEC plus aerobic F/bottle and BACTEC anaerobic lytic/10 bottle and comparison of the BACTEC plus aerobic F/bottle to the isolator tube for recovery of bacteria, mycobacteria, and fungi from blood. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:4380–4386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wages DS, Helfend L, Finkle H. Coccidioides immitis presenting as a hyphal form in a ventriculoperitoneal shunt. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1995;119:91–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:807–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]