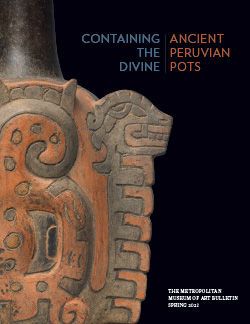

Prisoner jar

Not on view

This ceramic jar, from the Moche culture of the North Coast of Peru, represents a bound and kneeling prisoner. The white features of the prisoner’s fringed tunic, eyes and rope were produced by painting the normal reddish clay with a white slip (a slurry of fine clay or pigments) before firing. He wears a textile head wrap with a white striated border as well as a spread-winged owl or bat ornament in the front, likely representing a gilded copper headdress worn by high-status individuals (see accession number 1979.206.1227 in the Met’s collection and Pillsbury et al., 2017: cat. nos. 42, 46 for related examples). The tunic is decorated with inscribed squares, which may represent the textile pattern or possibly metal plates sewn onto a cloth undergarment, and terminates in a fringe of triangular shapes. A thick rope is around the figure’s neck and his crossed hands are bound at his back. He is depicted without a loin cloth, with exposed genitals.

In Moche art prisoners are often shown stripped of their clothing and other power attributes, such as weapons, headdresses, and earspools, as a sign of their defeat (Donnan and McClelland, 1999). Often prisoners with ropes around their necks and hands tied behind their backs are depicted being paraded by warriors. In this example, the empty holes in the figure’s earlobes, his exposed genitals, and his bound neck and hands clearly indicate his subjugated condition. Ceramic vessels similar to this jar were found in a sacrificial site at Huaca de la Luna, a major Moche mudbrick platform near the modern city of Trujillo (Bourget, 2001; Verano, 2008). The vessels had been intentionally smashed among the bodies of more than seventy sacrificed men. Like their ceramic representations, the actual human prisoners had tied hands and ropes around their necks.

The Moche (also known as the Mochicas) flourished on Peru’s North Coast from 200-850 AD, centuries before the rise of the Incas (Castillo, 2017). Over the course of some six centuries, the Moche built thriving regional centers from the Nepeña River Valley in the south to perhaps as far north as the Piura River, near the modern border with Ecuador, developing coastal deserts into rich farmlands and drawing upon the abundant maritime resources of the Pacific Ocean’s Humboldt Current. Although there is some debate as to whether the Moche ever formed a single centralized political entity, they shared unifying cultural traits such as religious practices (Donnan, 2010).

References and further reading

Bourget, Steve. “Rituals of Sacrifice: Its Practice at Huaca de la Luna and Its Representation in Moche Iconography,” in Moche Art and Archaeology in Ancient Peru, edited by Joanne Pillsbury (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2001), pp. 88–109.

Castillo, Luis Jaime. “Masters of the Universe: Moche Artists and Their Patrons,” in Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas, edited by Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017), pp. 24–31.

Donnan, Christopher B. and Donna McClelland. Moche Fineline Painting: Its Evolution and Its Artists (Los Angeles: University of California, Los Angeles; Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1999).

Donnan, Christopher B. “Moche State Religion,” in New Perspectives on Moche Political Organization, edited by Jeffrey Quilter and Luis Jaime Castillo (Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 2010), pp. 47–69.

Mujica Barreda, Elías, et al., El Brujo: Huaca Cao, Centro Ceremonial Moche en el Valle de Chicama (Lima: Fundación Wiese, 2007).

Pardo, Cecilia, and Julio Rucabado, editors. Moche y sus vecinos. Reconstruyendo identidades (Lima: Museo de Arte de Lima, 2016).

Pillsbury, Joanne, Timothy Potts, and Kim N. Richter, editors. Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017).

Verano, John W. “Communality and Diversity in Moche Human Sacrifice,” in The Art and Archeology of the Moche, edited by Steve Bourget and Kimberly L. Jones (Austin: The University of Texas Press, 2008), pp. 195–213.

This image cannot be enlarged, viewed at full screen, or downloaded.

This artwork is meant to be viewed from right to left. Scroll left to view more.