John Wesley Heath was born on December 15, 1844, in Ohio but moved to Terrell, Texas, with his family at a young age. There, he got involved in rustling and robbery. He also married twice, first to Mary Ann Redman in October 1867. What became of her is unknown. He married again in March 1869 and was known to have had three children – Myrtle, Kittie, and John.

However, by the early 1880’s he was living in Arizona, where he served as a deputy sheriff in Cochise County for a brief time. He soon found that the pay was not nearly as good as thievery, resigned, and went back to his outlaw ways.

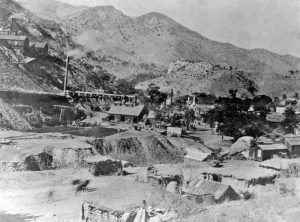

Living in Bisbee, Arizona, Heath opened a saloon and dance hall. In no time, it quickly became known as a hangout for area outlaws and other shiftless characters.

On December 8, 1883, five men held up the Goldwater and Castenada Store in Bisbee, leaving four people dead, including a pregnant woman. The vicious robbers included Daniel “Big Dan” Dowd, Comer W. “Red” Sample, Daniel “York” Kelly, William “Billy” Delaney, and James “Tex” Howard.

Having heard that a $7,000 payroll for the Copper Queen Mine was held for safekeeping in the store, two men charged inside demanding the money while the other three waited outside. However, to their disappointment, they discovered that the payroll had not yet arrived. Angered, they took what money was in the safe (reports vary from $900 to $3,000) and robbed the staff and customers of any valuables.

In the meantime, the three outlaws waiting outside began a shooting spree, first aiming through the window and killing a customer named J.C. Tappenier. Hearing the shot, Deputy Sheriff Tom Smith came running and was immediately shot down by the bandits. A bullet gone wild entered a boarding house, killing a pregnant Annie Roberts. Another shot hit a man named J.A. Nolly as he stood outside his office. Yet another unknown man took a bullet in the leg as he was trying to run away from the shooting spree.

The whole affair lasted less than five minutes, and with cash in hand and seemingly unperturbed, the outlaws left the town at a leisurely pace, evidently unworried about capture.

The town leaders wasted no time notifying Sheriff J.L. Ward in Tombstone by telegraph. Ward formed two posses, with himself leading one and Deputy Sheriff William Daniels leading another. When Daniels arrived in Bisbee, he questioned its citizens, including John Heath, whose saloon was just down the street from the Goldwater-Castaneda Mercantile. Heath told Daniels that he knew the men involved and could probably help lead them to the outlaws. Though Daniels was apprehensive of Heath, due to his already having a reputation as an unsavory character, he also hoped to apprehend the murderers quickly. With Heath at the lead, the posse found nothing and soon accused Heath of leading them on a false trail.

Heath returned to his saloon, and the posse continued to search for the outlaws. Though it took several weeks, all five were found, two in Mexico, one in New Mexico, and two in Clifton, Arizona.

When questioned, some of the outlaws began to indicate that John Heath knew more about the crime than he should have. Authorities brought Heath in and began to question him. Under pressure, Heath allegedly “fessed” up to having prior knowledge of the crime, and many believed that he probably masterminded the whole affair.

All were scheduled to be tried, but Heath requested a separate trial and was given it. Furious Bisbee citizens awaited the outcome of the outlaws involved in what had become known as the “Bisbee Massacre.” On February 17, the trial began for the five killers, and two days later, they were all sentenced to be hanged on March 8, 1884.

Heath’s trial began on February 20, where he admitted to being the mastermind of the robbery, indicating that the others lacked the intelligence. However, he adamantly insisted that the killings were never a part of the plan and that he was in no way responsible for the actions of the other five men. A coward at heart, he even admitted that when he heard the shots being fired, he hid behind the bar of his saloon. The next day, Heath was convicted of second-degree murder and conspiracy to commit robbery and sentenced to life in the Yuma prison.

Though Heath was obviously relieved, the citizens of Bisbee were furious and determined to do something about it. Early on the morning of February 22, a mob of some 50 men, led by Mike Shaughnessy, descended upon the Tombstone jail and dragged Heath from his cell into the dusty street.

At the corner of First and Toughnut Streets, they looped a rope over the crossbeam of a telegraph pole, as Heath continually claimed his innocence. The vigilantes were not listening. In his last moments, he said: “I have faced death too many times to be disturbed when it actually comes.” As the rope began to pull him skyward, he cried out one last request, “Don’t mutilate my body or shoot me full of holes!” Public approval of the hanging was reflected in the verdict of the coroner’s jury: “We the undersigned, a jury of inquest, find that John Heath came to his death from emphysema of the lungs–a disease common in high altitudes–which might have been caused by strangulation, self-inflicted or otherwise.”

The other five killers’ scheduled hanging for March 8 remained unchanged, taking on a carnival-like atmosphere. Free tickets were issued for the event, but when Sheriff Ward ran out of them, an enterprising businessman built bleachers around the gallows and began selling yet more tickets.

Though John Heath was lynched in Tombstone for masterminding the Bisbee Massacre, evidence shows that he was not buried at Boot Hill, as this marker indicates. Photo by Kathy Alexander.

However, a famous businesswoman, gold prospector, and spiritual caretaker, Nellie Cashman, objected adamantly to the circus that was surrounding the event. Outraged at the citizens’ behavior and feeling that no death should be “celebrated,” she soon befriended the five convicts, visiting them often and providing them with spiritual guidance. She pleaded with Sheriff Ward to place a curfew on the town when the hangings were to take place. Ward conceded, and the vast majority of interested onlookers were not allowed to watch the “event.” In the meantime, she and some friends had destroyed the bleachers that had been built. When the five men were standing on the gallows, reportedly, Dan Dowd remarked that the multi-gallows were a “regular choking machine.” Unfortunately, he was right; because of the five men, only one died of a broken neck, the other four died slowly of strangulation.

After they were executed, the men were buried in Tombstone’s Boot Hill cemetery. Cashman also found out there was a plan to rob the bodies from their graves for a medical school study. This too outraged the woman, and she hired two prospectors to guard the graves for ten days, which were left undisturbed and remain at Boot Hill today.

Though there is a marked grave today in Tombstone’s Boot Hill for John Heath, records indicate that he was returned to Terrell, Texas, and buried in the Oakland Cemetery by his family in an unmarked grave.

Today, it is disputed that Heath was guilty. Author David Grassie contends, based on his research, that Heath was probably innocent and questions the multiple hangings as well. You can see his discussion on that via our friends at the Arizona Ghost Riders here.

© Kathy Weiser/Legends of America, updated February 2022.

Historical Text – How the Papers Reported the Affair

February 24, 1884, New York Times

“How An Arizona Mob Disposed Of One Of The Bisbee Murderers: Tombstone, Arizona, February 23. — At 9 a.m. on Thursday, Judge Pinney sentenced John Heath to confinement in Yuma Penitentiary for life for complicity in the Bisbee murders. Twenty-four hours later, the dead body of Heath dangled from the crossbar of a telegraph pole near the foot of Toughnut Street, where it was suspended by a rope. The following are the particulars of the occurrence as near as can be gathered: About 8:30 yesterday morning, a crowd of men, mostly miners, numbering about 150, proceeded to the Courthouse. Arriving there, they detailed seven of their number from Bisbee, who entered and demanded that John Heath be turned over to them. The seven men approached the door leading to the corridor of the jail, and one of them knocked. Being about time for the Chinaman who brings food for the prisoners to arrive; Jailer Ward opened the door unsuspiciously and was immediately covered by weapons and told to give up the keys of the jail.

Seeing any attempt at resistance would be useless, he did as requested, and in a few minutes, the deputation was in the presence of the sought-for man. The crowd, which by this time had filled the spacious hall, started for the street. At the door, they were met by Sheriff Ward, who called on them in the name of the law to desist. The Sheriff was picked up and gently removed down the steps out of the way while the crowd started down the street on the run. The rope had been placed around Heath’s body, and about 20 men had hold of it. It never became taut during the run, the prisoner keeping up with the crowd and showing no signs of the white feather.

Arriving at the place selected for the hanging, one of the party climbed a telegraph pole and passed the rope over the crossbar. Heath pulled a handkerchief from his pocket and, placing it on his knee, coolly and deliberately folded it and, placing it over his eyes, asked someone in the crowd to tie it. This being done, he informed the crowd they were hanging an innocent man and would find it out when the others (meaning Dowd and his companions) were hanged. He told them he had faced death too often to be afraid and had but one request to make, namely, that they would not shoot into his body. He was told his last wish would be respected, and he told them he was ready. Countless hands grasped the rope. A run was made, and in a twinkling, the man was suspended to the pole.

The news spread about town rapidly, and in a few minutes, an immense crowd of men, women, and children congregated on the scene. The universal expression was, “Served him right.” That this opinion should be so prevalent is no doubt the result of the testimony at the trial, which was convincing to any mind of ordinary intelligence that Heath was a guilty accessory to the Bisbee murders.

The Coroner’s jury found as a verdict that Heath came to his death from “emphysema, which might have been caused by strangulation, self-inflicted or otherwise.” A placard was posted on the telegraph pole where Heath was found suspended and dead with the following inscription: “John Heath was hanged to this pole by citizens of Cochise County for participation in the Bisbee massacre as a proved accessory at 8:20 a.m., February 22, 1884, to advance Arizona.”

February 28, 1884, The Kaufman Sun, Terrell, Texas

“John Heath was taken by a mob from jail and hung in Tombstone. His remains were brought to Terrell and interred yesterday. He was a notorious gambler, burglar, horse, and cattle thief.”

Unknown Date, Report from Orson Pratt Brown, who lived in Bisbee and Tombstone in the 1880s

“I went to work for Morris & Cheers Mines, hauling lumber from the Chiricahua Mountains to Bisbee, Arizona. I stayed at this work for about a year. It was during this time that I met Dan Dowd. He was a huge man about 25 years old, over 6 feet tall, and weighed about 180 lbs. Dan Dowd was one of the drivers for the mine as I was, and we made several trips together through the mountains. We had to pass a little ranch on the White Water Creek located between the sawmill and Tombstone owned by a half-breed named Milt Hall and his partner Frank Buckles. Another driver, William Delaney, and Dowd became very good friends, and often they would stop at this little ranch while on the road.

One day Dan Dowd declared himself. He said the world owed him a living, and he’d be damned if he was going to work so hard anymore. Then he quit his job and went away for about two weeks. When he returned to the Hall-Buckles Ranch, he was accompanied by a chap named Johnny Heath, a dandy-looking man who was well-dressed and riding a fine-looking horse. He had two white-handled six-shooters, a Winchester rifle, and two belts of cartridges.

Heath stayed at the ranch for a couple of days and then went off to Bisbee while Dowd went north. When Dowd returned to the ranch a few days later, he brought with him three hard-looking men, Red, Tex, and Kelly. And soon after, when Hall and I came to the ranch with our oxen and loads of lumber, we found five men there. Dan Dowd, Red Sample, Tex Howard, Dan Kelly, and Billy DeLaney. I asked Hall what they were doing there, and he said they were looking to buy a ranch.

We traveled on and about sundown the next day – December 8, 1883, the day of the murders – we saw five horsemen off to the east of us. We couldn’t recognize them, but I knew the horses were from the Hall-Buckles Ranch. We made camp at the south of the Bisbee Canyon, and the next morning as we were getting breakfast, two men rode into camp. One was Heath. They drank a cup of coffee with us and told us there had been a hold-up in Bisbee the night before. The bandits had robbed the Copper Queen Store, and they had murdered two men and a woman. They said they were in a posse on their trail and that they had headed toward Tombstone.

My partner Walt was out rounding up the oxen, and about an hour later, five men approached. They had seen the smoke from our campfire and came over. It was Sheriff Daniels and his posse who had been following the trail of the bandits. They asked me whether I had seen any of them, and I took Sheriff Daniels over to one side and told him what I knew. I said that I had recognized two horses as being from the Hall-Buckles Ranch among the five horsemen that we had seen the day before. And that I suspected that Buckles himself knew something about it since these hard-looking men in company with Dan Dowd had been at the Hall-Buckles Ranch the week before. I also told him of the two horsemen who had just gone by. The sheriff thanked me and sent two men after the horsemen. He and the others went immediately to the Hall-Buckles Ranch and arrested Buckles. Buckles turned states evidence against the other men.”

Compiled and edited by Kathy Weiser-Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2021.

Also See: