Commodities: Cereal excess

Simply sign up to the Sustainability myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Towering like a missile above the Illinois prairie town of Monticello, the galvanised metal silo that Topflight Grain Co-operative has just added to its storage complex can hold an awful lot of corn: 19,000 tonnes.

Yet after a mild, wet summer – perfect for growing chunky ears of yellow corn – the extra space may not be enough. Derrick Bruhn, Topflight’s grain merchandiser, warns some of it will end up piled high in outdoor mounds as farmers dump their harvests.

“It will be difficult to find a place to put everything,” he says.

Illinois is at the centre of an astonishing rebound in global grain supplies. After almost a decade of shortfalls and price rises, agricultural commodities have declined to the cheapest in four years. The new abundance will have broad effects, weakening incomes of farmers and companies that supply them, fattening profit margins at food and biofuel companies and – eventually – slowing food price inflation for consumers in rich and poor countries alike.

As the largest agricultural exporter, the US sets the direction for world markets, traders say. Illinois and other states in America’s Midwestern “corn belt” are on track to produce a record US corn harvest for a second consecutive year. The soyabean crop will also be the largest ever, the government predicts.

This bounteous picture extends across the northern hemisphere. In Canada stocks of wheat, oats and barley have doubled from a year ago after huge crops on its western plains. Europe’s wheat and corn crops are forecast to break records.

Even the crisis between Russia and Ukraine has not hurt their standing in global grain markets. Despite banning food imports last month, Russia has been loading ships with massive exports of wheat and barley. Ukraine’s farmers, hungry for dollars, are also eager sellers of corn and wheat, executives say.

And China plans to add 50m tonnes of storage facilities by next year as it struggles with brimming inventories of corn and rice, according to the state-run China Daily newspaper.

“All of a sudden you’ve got great crops all over,” says Abdolreza Abbassian, senior grains economist at the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation in Rome. World stocks of cereals next year will be equal to 25 per cent of annual global consumption, the highest such ratio since 2003, the FAO estimates. Soft grain prices have helped push commodity indices to five-year lows.

The flush supply situation is a striking reversal from recent history. In 2007-08 low stocks ignited furious price rises and food riots in dozens of countries from Haiti to India. Russia’s cereals export ban, declared in August 2010 during a devastating heatwave, again raised grain prices to levels that some scholars say contributed to the Arab spring uprisings the following year. And in 2012 the worst drought since the Dust Bowl years of the 1930s scorched the US corn belt.

The swing towards surplus is all the more remarkable because many of the long-term trends that strain food supplies persist. The world population continues to grow and consumers in developing countries are eating more grain-fed meat. Biofuel refiners are pumping out plenty of ethanol, though they have throttled back their once-headlong pace of expansion. Climate change is making weather extremes more frequent, endangering crop yields.

But even when difficult weather returns – and indeed, odds slightly favour the El Niño pattern that is associated with extreme conditions – the large crops of 2013 and 2014 will leave a lasting legacy. With stocks replenished from critically low levels, the world has a cushion against the next supply shock.

“Stocks are like insurance. You keep them for the bad times,” says José Cuesta, senior economist at the World Bank. “They also have a psychological effect. It gives optimism to the markets. I think right now a certain optimism is settling into international markets.”

A year ago the corn and soyabean stocks in Topflight’s silo network had dwindled to 100,000 bushels (2,540 tonnes), Mr Bruhn says. Ahead of the harvest now under way, stocks have been rebuilt to 200,000 bushels despite robust demand from the industrial-scale food processing plants operated by the Archer Daniels Midland and Tate & Lyle companies in nearby Decatur.

Mr Bruhn says Topflight’s silos will hold 1.5m bushels by early September 2015. Much of it will remain there. “We can carry it three or four years,” he says.

“Carry”, an old grain merchants’ term embraced by financial traders, has returned to agricultural markets with a vengeance. Two years ago corn futures for December 2012 delivery were fetching $1.50 a bushel more than corn to be delivered this December – giving traders reason to sell, not store, their inventories.

This week, December 2014 corn was 68 cents cheaper than corn delivered in December 2016. Simply holding on to the corn until then will make easy money for anyone with access to affordable storage. This is one reason shares of companies such as ADM and Bunge, each with extensive grain-handling networks, have outperformed the US stock market since June. A large grain volume “allows us to pick up inputs at a fairly attractive price, and with low interest rates, the cost to finance inventories is very inexpensive,” says Ray Young, ADM’s chief financial officer.

…

It is a truism often heard in commodity markets: high prices are the best cure for high prices. And the price of grain has been high.

Corn surpassed $8 a bushel in July 2012, a time when US fields were baked by record heat. In 2005 the average corn price was $2. Wheat hit $9 in 2012, up from $3 seven years earlier.

Farmers took the cue. Globally, land cultivated in corn, soyabeans or wheat rose 11 per cent to 514m hectares between 2005-13, according to FAO statistics. In the US farmers planted record soyabean acreage this spring, an area larger than Finland or Malaysia. Environmentalists note some of this land was previously wildlife habitat.

In the county of Divide, North Dakota, on the US border with Canada, farmers are planting five times as much corn as a decade ago despite its extremely short growing season.

“We’re as far north as you can get,” says Cliff Orgaard, executive director at the federal Farm Service Agency for the county. “Demand for corn had been rising pretty steadily because of ethanol and feed and livestock prices, so producers up here wanted to try it.”

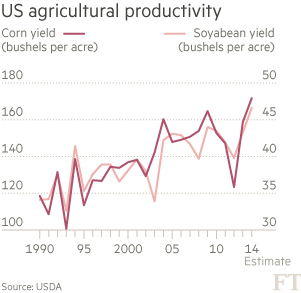

Yields – a measure of productivity – have been unpredictable in recent years as weather extremes offset technological advances such as self-steering tractors and biotech seeds. US soyabean yields peaked in 2009 at 44 bushels per acre, subsequently contracting as much as a 10th. This year soyabean yields will leap to about 46.6 bushels per acre.

Mr Young of ADM says: “I believe in the law of averages – in reversion to the mean. We had a few years of US yields that were significantly below trend. When I looked at the trend line, I was actually expecting at some juncture we’re going to have a home run in the United States.”

Viewed over a longer time horizon, climate change has begun to diminish wheat and maize (corn) yields, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has found. The National Climate Assessment report published for the US government warns of “increased uncertainty” for production totals. “Recent analysis suggests that climate change has an outsized influence on year-to-year swings in corn prices in the United States,” the assessment says.

While it might appear surprising, this year’s bumper US growing season has been consistent with climate projections, says Gene Takle of Iowa State University, a lead co-author of the climate assessment. States such as Iowa had heavy springtime rains, a regular feature of recent years. While rains can delay planting and cause erosion, moister soils also enable farmers to fit more corn stalks per acre, boosting yields.

“It’s doubtful in my mind that if we had the climate of the 1940s and 50s and 60s, whether these high populations could survive,” Prof Takle says.

What this summer lacked was the temperature extremes of recent years. Hot nights hurt corn yields in 2010 and 2012. “The extremes don’t happen that often but they are happening more often now than they were 30 years ago. Those trends are still in place,” Prof Takle says. “We’re seeing more of those, interspersed with a few very good years like we’re having now.”

When extremes next damage grain crops is anyone’s guess. A brutal drought damaged Brazil’s coffee trees this year but spared its corn and soyabean crops, the biggest in the southern hemisphere.

Still, the belief that future shortfalls will be offset by abundant stocks appears to be widespread. Governments in the Middle East – big buyers of wheat from the Black Sea region – are locking in supplies only three to six months ahead, barely extending purchases despite lower prices, says a trading industry executive. “They know that supply is there,” he says. “Nobody is going a year out.”

…

At Tyson Foods, a US-based beef, pork and chicken producer, the feed grain buying strategy will not change. “You’re going to have a favourable grain environment,” Donnie Smith, chief executive, said recently.

Analysts are starting to rethink assumptions. Earlier this year the US Department of Agriculture projected China would overtake Japan as the world’s top importer of corn in 2020.

Since then China’s corn imports have stalled. Shipments from the US virtually ended after Beijing claimed they contained a genetic trait not yet approved inside the country. Fred Gale, a USDA senior economist, says: “It’s puzzling. One of the questions we’re grappling with now is whether this is a blip or if this narrative of China needing to import is going ‘poof’.”

Another piston of grain demand in recent years has been biofuels. Spurred by government mandates and high oil prices, the amount of US corn refined into ethanol climbed from 1.6bn bushels in 2005 to more than 5bn this year. That market survives, but its future is in question as the White House plans cuts to consumption targets.

For farmers in the corn belt, the prospect of higher supplies and lower prices is unsettling.

“The last few years have been the golden age of farming,” says Terry Lieb, who farms 3,000 acres outside Monticello with his two sons. “But farming, if you’ve been in it very long, it all goes in cycles. Now it’s turned to a down cycle again. It’s going to get tough again for a few years.”

——————————————-

Poverty: Lower food prices are no panacea for the poor

Surges in the international price of staple grains have led to food riots over the past decade. But the recent fall in cereals prices is not necessarily a blessing for poorer countries, a new working paper from the World Bank has found.

In the short run, rises in global food prices tend to increase poverty because a large portion of poor people’s income is spent on food. Even many farming households are net buyers of food.

However, “higher food prices appear to lower global poverty in the long run”, because they raise wages for unskilled workers and encourage farmers to boost output. And evidence suggests that lower food prices increase poverty in the long term, says Will Martin, a research manager at the World Bank and co-author of the paper.

The findings illustrate the tangled effects of the lowest cereals prices in four years.

Consumers will see food-price inflation moderate. Grain prices will fall in real terms over the coming decade, according to an outlook by the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation and the OECD. Because of strong demand, however, meat prices will on average cost more than in the previous decade, the organisations say.

For farmers, the new global grain surplus brings winners and losers. After enjoying the highest real incomes in 40 years, US farmers’ profits will decline this year, the US Department of Agriculture estimates. But livestock revenues will climb as herd shortages brought on by drought and disease keep meat prices high.

Weaker farmer incomes will translate into lower land rental costs and pressure on sales of fertiliser and equipment. John Deere, the tractor and equipment maker, has announced more than 1,000 redundancies.

“If they’re not buying, we’re not building,” says Lucas DeSpain of the United Auto Workers’ union, representing Deere harvester employees in East Moline, Illinois.

Comments