Practice Essentials

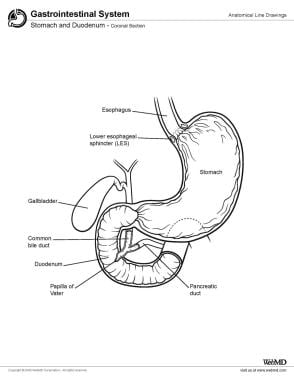

Gastric cancer is the sixth most common cancer and the fourth most common cause of cancer-related death in the world. [1] Although rates are low in North America and Northern Europe—in the United States, stomach malignancy is currently the 15th most common cancer [2] —the disease remains difficult to cure in Western countries, primarily because most patients present with advanced disease. See the image below.

Signs and symptoms

Early gastric cancer has no associated symptoms; however, some patients with incidental complaints are diagnosed with early gastric cancer. Most symptoms of gastric cancer reflect advanced disease. All physical signs in gastric cancer are late events. By the time they develop, the disease is almost invariably too far advanced for curative procedures.

Signs and symptoms of gastric cancer include the following:

-

Indigestion

-

Nausea or vomiting

-

Dysphagia

-

Postprandial fullness

-

Loss of appetite

-

Melena or pallor from anemia

-

Hematemesis

-

Weight loss

-

Palpable enlarged stomach with succussion splash

-

Enlarged lymph nodes such as Virchow nodes (ie, left supraclavicular) and Irish node (anterior axillary)

Late complications of gastric cancer may include the following features:

-

Pathologic peritoneal and pleural effusions

-

Obstruction of the gastric outlet, gastroesophageal junction, or small bowel

-

Bleeding in the stomach from esophageal varices or at the anastomosis after surgery

-

Intrahepatic jaundice caused by hepatomegaly

-

Extrahepatic jaundice

-

Inanition from starvation or cachexia of tumor origin

See Presentation for more detail.

Diagnosis

Testing

The goal of obtaining laboratory studies is to assist in determining optimal therapy. Potentially useful tests in patients with suspected gastric cancer include the following:

-

CBC: May be helpful to identify anemia, which may be caused by bleeding, liver dysfunction, or poor nutrition; approximately 30% of patients have anemia

-

Electrolyte panels

-

Liver function tests

-

Tumor markers such as CEA and CA 19-9: Elevated CEA in 45-50% of cases; elevated CA 19-9 in about 20% of cases

Imaging studies

Imaging studies that aid in the diagnosis of gastric cancer in patients in whom the disease is suggested clinically include the following:

-

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD): To evaluate gastric wall and lymph node involvement

-

Double-contrast upper GI series and barium swallows: May be helpful in delineating the extent of disease when obstructive symptoms are present or when bulky proximal tumors prevent passage of the endoscope to examine the stomach distal to an obstruction

-

Chest radiography: To evaluate for metastatic lesions

-

CT scanning or MRI of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis: To assess the local disease process and evaluate potential areas of spread

-

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS): Staging tool for more precise preoperative assessment of the tumor stage

Biopsy

Biopsy of any ulcerated lesion should include at least six specimens taken from around the lesion because of variable malignant transformation. In selected cases, endoscopic ultrasonography may be helpful in assessing depth of penetration of the tumor or involvement of adjacent structures.

Histologically, the frequency of different gastric malignancies is as follows [3] :

-

Adenocarcinoma - 90-95%

-

Lymphomas - 1-5%

-

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (formerly classified as either leiomyomas or leiomyosarcomas) - 2%

-

Carcinoids - 1%

-

Adenoacanthomas - 1%

-

Squamous cell carcinomas - 1%

See Workup for more detail.

Management

Surgery

The surgical approach in gastric cancer depends on the location, size, and locally invasive characteristics of the tumor.

Types of surgical intervention in gastric cancer include the following:

-

Total gastrectomy, if required for negative margins

-

Esophagogastrectomy for tumors of the cardia and gastroesophageal junction

-

Subtotal gastrectomy for tumors of the distal stomach

-

Lymph node dissection: Controversy exists regarding extent of dissection; the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends D2 dissections over D1 dissections; a pancreas- and spleen-preserving D2 lymphadenectomy provides greater staging information and may provide a survival benefit while avoiding its excess morbidity when possible [4]

Chemotherapy

Antineoplastic agents and combinations of agents used in managing gastric cancer include the following:

-

Platinum-based combination chemotherapy: First-line regimens include epirubicin/cisplatin/5-FU or docetaxel/cisplatin/5-FU; other regimens include irinotecan and cisplatin; other combinations include oxaliplatin and irinotecan

-

Trastuzumab in combination with cisplatin and capecitabine or 5-FU: For patients who have not received previous treatment for metastatic disease

-

Ramucirumab for the treatment of advanced stomach cancer or gastroesophageal (GE) junction adenocarcinoma in patients with unresectable or metastatic disease following therapy with a fluoropyrimidine- or platinum-containing regimen

-

Pembrolizumab for gastric or GE junction carcinoma in patients expressing PD-L1 with disease progression on or after 2 or more prior lines of therapy including fluoropyrimidine- and platinum-containing chemotherapy and if appropriate, HER2/neu-targeted therapy

-

Nivolumab in combination with fluoropyrimidine- and platinum-containing chemotherapy for first-line therapy of advanced or metastatic gastric cor GE junction cancer

-

Trastuzumab deruxtecan for locally advanced or metastatic HER2-positive gastric or GE junction adenocarcinoma in patients who have received a prior trastuzumab-based regimen

Neoadjuvant, adjuvant, and palliative therapies

Potentially useful therapies in gastric cancer include the following:

-

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy

-

Intraoperative radiotherapy (IORT)

-

Adjuvant chemotherapy (eg, 5-FU)

-

Adjuvant radiotherapy

-

Adjuvant chemoradiotherapy

-

Palliative radiotherapy

-

Palliative-intent procedures (eg, wide local excision, partial gastrectomy, total gastrectomy, simple laparotomy, gastrointestinal anastomosis, bypass)

See Treatment for more detail.

For patient education resources, see Stomach Cancer.

Background

Gastric cancer was once the second most common cancer in the world. In most developed countries, however, rates of stomach cancer have declined dramatically over the past half century. In the United States, stomach malignancy is currently the 15th most common cancer. [2]

Decreases in gastric cancer have been attributed in part to widespread use of refrigeration, which has had several beneficial effects: increased consumption of fresh fruits and vegetables; decreased intake of salt, which had been used as a food preservative; and decreased contamination of food by carcinogenic compounds arising from the decay of unrefrigerated meat products. Salt and salted foods may damage the gastric mucosa, leading to inflammation and an associated increase in DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. Other factors likely contributing to the decline in stomach cancer rates include lower rates of chronic Helicobacter pylori infection, thanks to improved sanitation and use of antibiotics, and increased screening in some countries. [5]

Nevertheless, gastric cancer remains difficult to cure in Western countries, primarily because most patients present with advanced disease. Even patients who present in the most favorable condition and who undergo curative surgical resection often die of recurrent disease. However, two studies have demonstrated improved survival with adjuvant therapy: a US study using postoperative chemoradiation [6] and a European study using preoperative and postoperative chemotherapy. [7]

Anatomy

Management of stomach cancer requires a thorough understanding of gastric anatomy. An image depicting stomach anatomy can be seen below.

The stomach begins at the gastroesophageal junction and ends at the duodenum. The stomach has three parts: the uppermost part is the cardia; the middle and largest part is the body, or fundus; and the distal portion, the pylorus, connects to the duodenum. These anatomic zones have distinct histologic features. The cardia contains predominantly mucin-secreting cells. The fundus contains mucoid cells, chief cells, and parietal cells. The pylorus is composed of mucus-producing cells and endocrine cells.

The stomach wall is made up of five layers. From the lumen out, the layers are as follows:

-

Mucosa

-

Submucosa

-

Muscularis

-

Subserosa

-

Serosa

Externally, the peritoneum of the greater sac covers the anterior surface of the stomach. A portion of the lesser sac drapes posteriorly over the stomach. The gastroesophageal junction has limited or no serosal covering.

The right portion of the anterior gastric surface is adjacent to the left lobe of the liver and the anterior abdominal wall. The left portion of the stomach is adjacent to the spleen, the left adrenal gland, the superior portion of the left kidney, the ventral portion of the pancreas, and the transverse colon.

The site of stomach cancer is classified on the basis of its relationship to the long axis of the stomach. Approximately 40% of cancers develop in the lower part, 40% in the middle part, and 15% in the upper part; 10% involve more than one part of the organ. Most of the decrease in gastric cancer incidence and mortality in the United States has involved cancer in the lower part of the stomach; the incidence of adenocarcinoma in the cardia has actually shown a gradual increase.

Pathophysiology

Ooi et al identified three oncogenic pathways that are deregulated in the majority (>70%) of gastric cancers: the proliferation/stem cell, NF-kappaβ, and Wnt/beta-catenin pathways. Their study suggests that interactions between these pathways may play an important role in influencing disease behavior and patient survival. [8]

The intestinal type of non-cardia gastric cancer is generally thought to arise from Helicobacter pylori infection, which initiates a sequence that progresses from chronic non-atrophic gastritis to atrophic gastritis, then intestinal metaplasia, and finally dysplasia. This progression is known as Correa’s cascade. In a population-based cohort study, Swedish researchers found that after a 2-year latency, patients with precancerous gastric lesions were at higher risk for gastric cancer than the general Swedish population, and that risk increased steadily with progression through Correa’s cascade. The researchers estimated that the 20-year gastric cancer risk in patients with particular gastroscopy findings was as follows [9] :

-

Normal mucosa – One in 256

-

Gastritis – One in 85

-

Atrophic gastritis – One in 50

-

Intestinal metaplasia – One in 39

-

Dysplasia – One in 19

Hematogenous and lymphatic spread

Understanding the vascular supply of the stomach allows understanding of the routes of hematogenous spread. The vascular supply of the stomach is derived from the celiac artery. The left gastric artery, a branch of the celiac artery, supplies the upper right portion of the stomach. The common hepatic artery branches into the right gastric artery, which supplies the lower portion of the stomach, and the right gastroepiploic branch, which supplies the lower portion of the greater curvature.

Understanding the lymphatic drainage can clarify the areas at risk for nodal involvement by cancer. The lymphatic drainage of the stomach is complex. Primary lymphatic drainage is along the celiac axis. Minor drainage occurs along the splenic hilum, suprapancreatic nodal groups, porta hepatis, and gastroduodenal areas.

Etiology

Gastric cancer may often be multifactorial, involving both inherited predisposition and environmental factors. [10] Environmental factors implicated in the development of gastric cancer include the following:

-

Diet

-

Helicobacter pylori infection

-

Previous gastric surgery

-

Pernicious anemia

-

Adenomatous polyps

-

Chronic atrophic gastritis

-

Radiation exposure

Diet

A diet rich in pickled vegetables, salted fish, salt, and smoked meats correlates with an increased incidence of gastric cancer. [10]

A diet that includes fruits and vegetables rich in vitamin C may have a protective effect. [11]

Smoking

Smoking is associated with an increased incidence of stomach cancer in a dose-dependent manner, both for number of cigarettes and for duration of smoking. Smoking increases the risk of cardiac and noncardiac forms of stomach cancer. [12] Cessation of smoking reduces the risk. A meta-analysis of 40 studies estimated that the risk was increased by approximately 1.5- to 1.6-fold and was higher in men. [13]

Helicobacter pylori infection

Chronic bacterial infection with H pylori is the strongest risk factor for stomach cancer.

H pylori may infect 50% of the world's population, but many fewer than 5% of infected individuals develop cancer. It may be that only a particular strain of H pylori is strongly associated with malignancy, probably because it is capable of producing the greatest amount of inflammation. In addition, full malignant transformation of affected parts of the stomach may require that the human host have a particular genotype of interleukin (IL) to cause the increased inflammation and an increased suppression of gastric acid secretion. For example, IL-17A and IL-17F are inflammatory cytokines that play a critical role in inflammation. Wu et al found that carriage of IL-17F 7488GA and GG genotypes were associated with an increased risk of gastric cancer. [14]

A Japanese study in 10,426 patients with gastric cancer and 38,153 controls identified a combined effect of pathogenic variants in cancer-predisposing genes and H pylori infection on the risk of gastric cancer. Elevated risk of gastric cancer was found in association with germline pathogenic variants in nine genes (APC, ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDH1, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PALB2). Cumulative risk of gastric cancer by 85 years of age was higher in persons who carried pathogenic variants in homologous-recombination genes and H pylori infection than in noncarriers with H pylori (45.5% [95% CI, 20.7 to 62.6] vs. 14.4% [95% CI, 12.2 to 16.6]). [15]

H pylori infection is associated with chronic atrophic gastritis, and patients with a history of prolonged gastritis have a sixfold increased risk of developing gastric cancer. Interestingly, this association is particularly strong for tumors located in the antrum, body, and fundus of the stomach but does not seem to hold for tumors originating in the cardia. [16]

A large-scale, long-term study from Korea—which along with China and Japan is a high-risk country for gastric cancer—concluded that in patients with a family history of gastric cancer, treatment of H pylori infection more than halves their risk of developing gastric cancer. In the study, which included 1676 patients ages 40 to 65 years with confirmed H pylori infection and at least one first-degree relative with gastric cancer, patients were randomized to triple antibiotic therapy or placebo and followed with surveillance endoscopy every 2 years. [17]

Over a median follow-up of 9.2 years, gastric cancer developed in 1.2% of patients in the treatment group, versus 2.7% of those in the placebo group. Among patients with persistent infection (n = 979), gastric cancer developed in 2.9%, compared with 0.8% of those in whom the infection had been eradicated (hazard ratio, 0.27). [17]

A study by Cheung et al found that risk of gastric cancer was increased in patients who used proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) long-term after successful treatment for H pylori infection. [18] In the study, which included 63,397 patients from a territory-wide Hong Kong health database with a median follow-up of 7.6 years, PPIs use was associated with more than a doubled risk of gastric cancer (hazard ratio [HR] 2.44; 95% confidence index [CI], 1.42 to 4.20). The risk increased with duration of PPIs use, as follows:

-

≥1 year - HR 5.04 (95% CI 1.23–20.61)

-

≥2 years - HR 6.65 (95% CI 1.62–27.26)

-

≥3 years - HR 8.34 (95% CI 2.02–34.41)

The relevance of this study to clinical practice remains uncertain, however, as the results could be due to residual confounding or detection bias. [19]

Previous gastric surgery

Previous surgery is implicated as a risk factor. The rationale is that surgery alters the normal pH of the stomach, which may in turn lead to metaplastic and dysplastic changes in luminal cells. [20]

Retrospective studies demonstrate that a small percentage of patients who undergo gastric polyp removal have evidence of invasive carcinoma within the polyp. This discovery has led some researchers to conclude that polyps might represent premalignant conditions.

Genetic factors

Some 10% of stomach cancer cases are familial in origin. Genetic factors involved in gastric cancer remain poorly understood, though specific mutations have been identified in a subset of gastric cancer patients. For example, germline truncating mutations of the E-cadherin gene (CDH1) are detected in 50% of diffuse-type gastric cancers, and families that harbor these mutations have an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance with a very high penetrance. [21]

Other hereditary syndromes with a predisposition for stomach cancer include the following:

-

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer

Other factors

See the list below:

-

Infection with the Epstein-Barr virus may be associated with a rare (< 1%) form of stomach cancer, lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma.

-

Pernicious anemia associated with advanced atrophic gastritis and intrinsic factor deficiency is a risk factor for gastric carcinoma.

-

Gastric cancer may develop in the remaining portion of the stomach following a partial gastrectomy for gastric ulcer. Benign gastric ulcers may themselves develop into malignancy.

-

Obesity increases the risk of gastric cardia cancer.

-

Radiation exposure: Survivors of atomic bomb blasts have had an increased rate of stomach cancer. Other populations exposed to radiation may also have an increased rate of stomach cancer.

Bisphosphonates

A large cohort study examined whether use of oral bisphosphonates was associated with an increased risk of esophageal or gastric cancers. No significant difference was observed for increased risk of esophageal or gastric cancers between the bisphosphonate cohort and the control group. [22]

Epidemiology

United States

The American Cancer Society estimates that about 26,890 cases of stomach cancer (16,160 in men and 10,730 in women) will be diagnosed in 2024. [23] Median age at diagnosis is 68 years. From 2012–2021, the rate of new stomach cancer cases has been relatively stable. Gastric cancer is the 15th most common cancer in the US. [2]

International

Once the second most common cancer worldwide, stomach cancer has dropped to sixth place, after cancers of the female breast, lung, colon and rectum, and prostate. [5] Stomach cancer is the fourth most common cause of death from cancer. [5] The World Health Organization estimates that in 2020, gastric cancer accounted for 769,000 deaths worldwide. [1]

Tremendous geographic variation exists in the incidence of this disease around the world. Rates of the disease are low in Africa, North America, and northern Europe, and highest in eastern Asia (eg, Mongolia, Japan, the Republic of Korea) and eastern Europe. The highest death rates are recorded in south central Asian countries, including Iran, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, and Kyrgyzstan. [5]

Using data from 92 cancer registries in 34 countries representing 10 world regions, Arnold et al predicted that overall gastric cancer incidence rates will continue falling in most countries, including high-incidence countries such as Japan as well as low-incidence ones such as Australia. By 2035, incidence rates in 16 of those 34 countries will fall below the rare disease threshold (defined as 6 per 100,000 person-years). [24]

Nevertheless, the absolute number of new gastric cancer cases is expected to increase in the majority of countries. New cases could double in Canada, Cyprus, South Korea, Slovakia, and Thailand, while dropping slightly in a few other countries (eg, Bulgaria, Lithuania). [24]

While decreasing or stable incidence rates were consistently observed in people aged 50 years and above, Arnold et al predicted increases in incidence in those younger than 50 years in 15 of 34 countries, including Belarus, Chile, the Netherlands, Canada, and the United Kingdom. [24]

Mortality/Morbidity

In the United States, gastric cancer represents 1.5% of all new cancer cases but 1.8% of cancer deaths. The overall 5-year relative survival rate, which was 14.3% in 1975, rose to 32.0% by 2010-2016. During that period, the 5-year relative survival rate by stage at diagnosis was 69.5% for localized disease, 32.0% for regional disease, and 5.5% for distant disease. [2] Worldwide, gastric cancer is the third leading cause of cancer death, with the highest rates reported in East Asia, South America and Eastern Europe. [1]

Race

The rates of gastric cancer are higher in Asian and South American countries than in the United States; in Japan, for example, stomach cancer is the most common cancer site in males. [5] Japan, Chile, and Venezuela have developed a very rigorous early screening program that detects patients with early-stage disease (ie, low tumor burden). These patients appear to do quite well. In fact, in many Asian studies, patients with resected stage II and III disease tend to have better outcomes than similarly staged patients treated in Western countries. Some researchers suggest that this reflects a fundamental biologic difference in the disease as it manifests in Western countries.

In the United States, the incidence of stomach cancer in males is highest in blacks, followed by Asians and Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, and American Indian/Alaska natives. In females, rates are highest in Asians and Pacific Islanders, followed by blacks and Hispanics and American Indian/Alaska natives. In both males and females, rates are lowest in whites. [2]

Sex- and age-related demographics

In the United States, gastric cancer affects slightly more men than women; the American Cancer Society estimated that in 2020, 16,980 new cases would be diagnosed in men and 10,620 in women. [23] Worldwide, however, gastric cancer rates are about twice as high in men as in women. [5]

The median age at gastric cancer diagnosis in the United States is 68 years; fewer than 2% of cases occur in persons younger than 35 years. [2] The gastric cancers that occur in younger patients may represent a more aggressive variant or may suggest a genetic predisposition to development of the disease.

Prognosis

Unfortunately, only a minority of patients with gastric cancer who undergo surgical resection will be cured of their disease. Most patients have a recurrence.

Patterns of failure

Several studies have investigated the patterns of failure after surgical resection alone. Studies that depend solely on the physical examination, laboratory studies, and imaging studies may overestimate the percentage of patients with distant failure and underestimate the incidence of local failure, which is more difficult to detect.

A reoperation series from the University of Minnesota may offer a more accurate understanding of the biology of the disease. In this series of patients, researchers surgically reexplored patients 6 months after the initial surgery and meticulously recorded the patterns of disease spread. The total local-regional failure rate approached 67%. The gastric bed was the site of failure in 54% of these cases, and the regional lymph nodes were the site of failure in 42%. Approximately 26% of patients had evidence of distant failure. The patterns of failure included local tumor regrowth, tumor bed recurrences, regional lymph node failures, and distant failures (ie, hematogenous failures and peritoneal spread). Primary tumors involving the gastroesophageal junction tended to fail in the liver and the lungs. Lesions involving the esophagus failed in the liver. [25]

-

Stomach and duodenum, coronal section.

-

Early gastric cancer in the gastric body. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons (author Med_Chaos).

Tables

What would you like to print?

- Overview

- Presentation

- DDx

- Workup

- Treatment

- Guidelines

- Medication

- Medication Summary

- Antineoplastics, Antimetabolite

- Antineoplastics, Platinum Analog

- Antineoplastics, Anthracycline

- Antineoplastics, Topoisomerase Inhibitors

- Antineoplastics, Antimicrotubular (Taxanes)

- Antineoplastics, Anti-HER2

- Antineoplastics, VEGF Inhibitor

- PD-1/PD-L1 Inhibitors

- Thymidine Analog

- Show All

- Questions & Answers

- Media Gallery

- References