Practice Essentials

Anemia is strictly defined as a decrease in red blood cell (RBC) mass. The function of the RBC is to deliver oxygen from the lungs to the tissues and carbon dioxide from the tissues to the lungs. This is accomplished by using hemoglobin (Hb), a tetramer protein composed of heme and globin. In anemia, a decrease in the number of RBCs transporting oxygen and carbon dioxide impairs the body’s ability for gas exchange. The decrease may result from blood loss, increased destruction of RBCs (hemolysis), or decreased production of RBCs. [1]

Anemia, like a fever, is a sign that requires investigation to determine the underlying etiology. Often, practicing physicians overlook mild anemia. This is similar to failing to seek the etiology of a fever. The purpose of this article is to provide a method of determining the etiology of an anemia. (See the image below.) (See Etiology, Presentation, and Workup.)

Methods for measuring RBC mass are time consuming and expensive and usually require transfusion of radiolabeled erythrocytes. Thus, in practice, anemia is usually discovered and quantified by measurement of the RBC count, Hb concentration, and hematocrit (Hct). These values should be interpreted cautiously, because they are concentrations affected by changes in plasma volume. For example, dehydration elevates these values, and increased plasma volume in pregnancy can diminish them without affecting the RBC mass. [2] (See Workup.)

Complications

The most serious complications of severe anemia arise from tissue hypoxia. Shock, hypotension, or coronary and pulmonary insufficiency can occur. This is more common in older individuals with underlying pulmonary and cardiovascular disease. (See Pathophysiology.)

Pathophysiology

Erythrocyte life cycle

Erythroid precursors develop in bone marrow at rates usually determined by the requirement for sufficient circulating Hb to oxygenate tissues adequately. Erythroid precursors differentiate sequentially from stem cells to progenitor cells to erythroblasts to normoblasts in a process requiring growth factors and cytokines. [3] This process of differentiation requires several days. Normally, erythroid precursors are released into circulation as reticulocytes.

Reticulocytes are so called because of the reticular meshwork of rRNA they harbor. They remain in the circulation for approximately 1 day before they mature into erythrocytes, after the digestion of RNA by reticuloendothelial cells. The mature erythrocyte remains in circulation for about 120 days before being engulfed and destroyed by phagocytic cells of the reticuloendothelial system.

Erythrocytes are highly deformable and increase their diameter from 7 µm to 13 µm when they traverse capillaries with a 3-µm diameter. They possess a negative charge on their surface, which may serve to discourage phagocytosis. Because erythrocytes have no nucleus, they lack a Krebs cycle and rely on glycolysis via the Embden-Meyerhof and pentose pathways for energy. Many enzymes required by the aerobic and anaerobic glycolytic pathways decrease within the cell as it ages. In addition, the aging cell has a decrease in potassium concentration and an increase in sodium concentration. These factors contribute to the demise of the erythrocyte at the end of its 120-day lifespan.

Response to anemia

The physiologic response to anemia varies according to acuity and the type of insult. Gradual onset may allow for compensatory mechanisms to take place. With anemia due to acute blood loss, a reduction in oxygen-carrying capacity occurs along with a decrease in intravascular volume, with resultant hypoxia and hypovolemia. Hypovolemia leads to hypotension, which is detected by stretch receptors in the carotid bulb, aortic arch, heart, and lungs. These receptors transmit impulses along afferent fibers of the vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves to the medulla oblongata, cerebral cortex, and pituitary gland.

In the medulla, sympathetic outflow is enhanced, while parasympathetic activity is diminished. Increased sympathetic outflow leads to norepinephrine release from sympathetic nerve endings and discharge of epinephrine and norepinephrine from the adrenal medulla. Sympathetic connection to the hypothalamic nuclei increases antidiuretic hormone (ADH) secretion from the pituitary gland. [4] ADH increases free water reabsorption in the distal collecting tubules. In response to decreased renal perfusion, juxtaglomerular cells in the afferent arterioles release renin into the renal circulation, leading to increased angiotensin I, which is converted by angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) to angiotensin II.

Angiotensin II has a potent pressor effect on arteriolar smooth muscle. Angiotensin II also stimulates the zona glomerulosa of the adrenal cortex to produce aldosterone. Aldosterone increases sodium reabsorption from the proximal tubules of the kidney, thus increasing intravascular volume. The primary effect of the sympathetic nervous system is to maintain perfusion to the tissues by increasing systemic vascular resistance (SVR). The augmented venous tone increases the preload and, hence, the end-diastolic volume, which increases stroke volume. Therefore, stroke volume, heart rate, and SVR all are maximized by the sympathetic nervous system. Oxygen delivery is enhanced by the increased blood flow.

In states of hypovolemic hypoxia, the increased venous tone due to sympathetic discharge is thought to dominate the vasodilator effects of hypoxia. Counterregulatory hormones (eg, glucagon, epinephrine, cortisol) are thought to shift intracellular water to the intravascular space, perhaps because of the resultant hyperglycemia. This contribution to the intravascular volume has not been clearly elucidated.

Etiology

Basically, only three causes of anemia exist: blood loss, increased destruction of RBCs (hemolysis), and decreased production of RBCs. Each of these causes includes a number of disorders that require specific and appropriate therapy. Genetic etiologies include the following:

-

Hemoglobinopathies

-

Thalassemias

-

Enzyme abnormalities of the glycolytic pathways

-

Defects of the RBC cytoskeletonCongenital dyserythropoietic anemia

-

Rh null disease

-

Hereditary xerocytosis

-

Abetalipoproteinemia

Nutritional etiologies include the following:

-

Iron deficiency

-

Vitamin B12 deficiency

-

Folate deficiency

-

Starvation and generalized malnutrition

Physical etiologies include the following:

-

Trauma

-

Burns

-

Frostbite

-

Prosthetic valves and surfaces

Chronic disease and malignant etiologies include the following:

-

Kidney disease

-

Liver disease

-

Chronic infections

-

Neoplasia

-

Collagen vascular diseases

Infectious etiologies include the following:

-

Viral - Hepatitis, infectious mononucleosis, cytomegalovirus

-

Bacterial - Clostridia, gram-negative sepsis

-

Protozoal - Malaria, leishmaniasis, toxoplasmosis

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and hemolytic-uremic syndrome may be a cause of anemia. Hereditary spherocytosis either may present as a severe hemolytic anemia or may be asymptomatic with compensated hemolysis. Similarly, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G-6-PD) deficiency may manifest as chronic hemolytic anemia or exist without anemia until the patient receives an oxidant medication. Immunologic etiologies for anemia may include antibody-mediated abnormalities. In the emergency department (ED), acute hemorrhage is by far the most common etiology for anemia.

Drugs or chemicals commonly cause the aplastic and hypoplastic group of disorders. Certain types of these causative agents are dose related and others are idiosyncratic. Any human exposed to a sufficient dose of inorganic arsenic, benzene, radiation, or the usual chemotherapeutic agents used for treatment of neoplastic diseases develops bone marrow depression with pancytopenia.

Conversely, among the idiosyncratic agents, only an occasional human exposed to these drugs has an untoward reaction resulting in suppression of one or more of the formed elements of bone marrow (1:100 to 1:millions). With certain types of these drugs, pancytopenia is more common, whereas with others, suppression of one cell line is usually observed. Thus, chloramphenicol may produce pancytopenia, whereas granulocytopenia is more frequently observed with toxicity to sulfonamides or antithyroid drugs.

Current evidence suggests that susceptibility to idiosyncratic reactions involves certain genetic polymorphisms involving cellular detoxifying enzymes. As a result, exogenous toxins that would normally be converted to nontoxic compounds are instead metabolized into reactive compounds that modify cellular proteins, which can be recognized by the immune system and trigger autoimmunity. [5]

The idiosyncratic causes of bone marrow suppression include multiple drugs in each of the categories that can be prefixed with anti- (eg, antibiotics, antimicrobials, anticonvulsants, antihistamines). The other idiosyncratic causes of known etiology are viral hepatitis and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria. In approximately one half of patients presenting with aplastic anemia, a definite etiology cannot be established, and the anemia must be regarded as idiopathic.

Rare causes of anemia due to a hypoplastic bone marrow include familial disorders and the acquired pure red cell aplasias. The latter are characterized by a virtual absence of erythroid precursors in the bone marrow, with normal numbers of granulocytic precursors and megakaryocytes. Rare causes of diminished erythrocyte production with hyperplastic bone marrow include hereditary orotic aminoaciduria and erythremic myelosis.

A study of 2688 patients undergoing cardiac surgery in the United Kingdom from 2008-2009 found that 1463 (54.4%) met the World Health Organization definition for anemia. This prevalence was much greater than previously reported, although the reason for this association is unclear. [6]

Epidemiology

Occurrence in the United States

The prevalence of anemia in population studies of healthy, nonpregnant people depends on the Hb concentration chosen for the lower limit of normal values. The World Health Organization (WHO) chose 12.5 g/dL for both adult males and females. In the United States, limits of 13.5 g/dL for men and 12.5 g/dL for women are probably more realistic. Using these values, approximately 4% of men and 8% of women have values lower than those cited. A significantly greater prevalence is observed in patient populations. Less information is available regarding studies using RBC or Hct.

International occurrence

The prevalence of anemia in Canada and northern Europe is believed to be similar to that in the United States.

A retrospective cohort study of tertiary hospital admissions in Western Australia found that 45,675 of 80,765 inpatients (56.55%) had anemia during their hospital stay. More than one third of patients who were not anemic on admission developed anemia during their stay. Even mild anemia was independently associated with increased mortality and length of stay. [7]

In underprivileged countries, limited studies of purportedly healthy subjects show the prevalence of anemia to be 2-5 times greater than that in the United States. Although geographic diseases, such as sickle cell anemia, thalassemia, malaria, hookworm, and chronic infections, are responsible for a portion of the increase, nutritional factors with iron deficiency and, to a lesser extent, folic acid deficiency play major roles in the increased prevalence of anemia. Populations with little meat in the diet have a high incidence of iron deficiency anemia, because heme iron is better absorbed from food than inorganic iron.

Sickle cell disease is common in regions of Africa, India, Saudi Arabia, and the Mediterranean basin. The thalassemias are the most common genetic blood diseases and are found in Southeast Asia and in areas where sickle cell disease is common.

Race-related demographics

Certain races and ethnic groups have an increased prevalence of genetic factors associated with certain anemias. Diseases such as the hemoglobinopathies, thalassemia, and G-6-PD deficiency have different morbidity and mortality in different populations due to differences in the genetic abnormality producing the disorder. For example, G-6-PD deficiency and thalassemia have less morbidity in African Americans than in Sicilians because of differences in the genetic fault. Conversely, sickle cell anemia has greater morbidity and mortality in African Americans than in Saudi Arabians.

Race is a factor in nutritional anemias and anemia associated with untreated chronic illnesses to the extent that socioeconomic advantages are distributed along racial lines in a given area; [8] socioeconomic advantages that positively affect diet and the availability of health care lead to a decreased prevalence of these types of anemia. [9, 10, 11] For instance, iron deficiency anemia is much more prevalent in the populations of developing nations, who tend to have little meat in their diets, than it is in populations of the United States and northern Europe.

Similarly, anemia of chronic disorders is commonplace in populations with a high incidence of chronic infectious disease (eg, malaria, tuberculosis, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]), and this is at least in part worsened by the socioeconomic status of these populations and their limited access to adequate health care.

Sex-related demographics

Overall, anemia is twice as prevalent in females as in males. This difference is significantly greater during the childbearing years due to pregnancies and menses.

Approximately 65% of body iron is incorporated into circulating Hb. One gram of Hb contains 3.46 mg of iron (1 mL of blood with an Hb concentration of 15 g/dL = 0.5 mg of iron). Each healthy pregnancy depletes the mother of approximately 500 mg of iron. While a man must absorb about 1 mg of iron to maintain equilibrium, a premenopausal woman must absorb an average of 2 mg daily. Further, because women eat less food than men, they must be more than twice as efficient as men in the absorption of iron to avoid iron deficiency.

Women have a markedly lower incidence of X-linked anemias, such as G-6-PD deficiency and sex-linked sideroblastic anemias, than men do. In addition, in the younger age groups, males have a higher incidence of acute anemia from traumatic causes.

Age-related demographics

Previously, severe, genetically acquired anemias (eg, sickle cell disease, thalassemia, Fanconi syndrome) were more commonly found in children because they did not survive to adulthood. However, with improvement in medical care and breakthroughs in transfusion and iron chelation therapy, in addition to fetal hemoglobin modifiers, the life expectancy of persons with these diseases has been significantly prolonged. [12]

Acute anemia has a bimodal frequency distribution, affecting mostly young adults and persons in their late fifties. Causes among young adults include trauma, menstrual and ectopic bleeding, and problems of acute hemolysis. During their childbearing years, women are more likely to become iron deficient.

In people aged 50-65 years, acute anemia is usually the result of acute blood loss in addition to a chronic anemic state. This is the case in uterine and GI bleeding.

Neoplasia increases in prevalence with each decade of life and can produce anemia from bleeding, from the invasion of bone marrow with tumor, or from the development of anemia associated with chronic disorders. The use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and warfarin also increases with age and can produce GI bleeding.

Prognosis

Usually, the prognosis depends on the underlying cause of the anemia. However, the severity of the anemia, its etiology, and the rapidity with which it develops can each play a significant role in the prognosis. Similarly, the age of the patient and the existence of other comorbid conditions influence outcome.

Sickle cell anemia

Patients who are homozygous (Hgb SS) have the worst prognosis, because they tend to have more frequent crises. Patients who are heterozygous (Hgb AS) have sickle cell traits, and they have crises only under extreme conditions.

Thalassemias

Patients who are homozygous for beta thalassemia (Cooley anemia or thalassemia major) have a worse prognosis than do patients with any of the other thalassemias (thalassemia intermedia and thalassemia minor). These few years have witnessed groundbreaking advancements in the treatment of thalassemias, especially with iron chelation therapies, allowing thalassemia patients to live well into adulthood. [12] Patients who are heterozygous for beta thalassemia have mild microcytic anemia that is not clinically significant.

Aplastic anemia

Chances of survival are poorer for patients with idiosyncratic aplasia caused by chloramphenicol and viral hepatitis and better when paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria or insecticide toxicity are the probable etiology. The prognosis for idiopathic aplasia lies between these 2 extremes, with an untreated mortality rate of approximately 60-70% within 2 years after diagnosis.

The 2-year fatality rate for severe aplastic anemia is 70% without bone marrow transplantation or a response to immunosuppressive therapy.

Hyperplasia

Among patients with a hyperplastic bone marrow and decreased production of RBCs, one group has an excellent prognosis, and the other is unresponsive, refractory to therapy, and has a relatively poor prognosis. The former includes patients with disorders of relative bone marrow failure due to nutritional deficiency, in whom identification of the etiology and treatment with vitamin B12, folic acid, or iron leads to a correction of anemia once the appropriate etiology is established. Drugs acting as an antifolic antagonist or inhibitor of DNA synthesis can produce similar effects.

The second group includes patients with an idiopathic hyperplasia that may respond partially to pyridoxine therapy in pharmacologic doses but more frequently does not. These patients have ringed sideroblasts in the bone marrow, indicating an inappropriate use of iron in the mitochondria for heme synthesis.

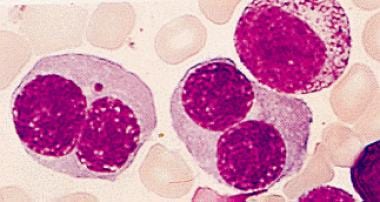

Certain patients with marrow hyperplasia (see the image below) may have refractory anemia for years, but some of the group eventually develop acute myelogenous leukemia.

Hemolytic-uremic syndrome

Hemolytic-uremic syndrome carries a significant morbidity and mortality if untreated. As many as 40% of those affected die, and as many as 80% develop renal insufficiency.

Patient Education

Inform patients of the etiology of their anemia, the significance of their medical condition, and the therapeutic options available for treatment.

If no effective specific treatment of the underlying disease exists, educate patients who require periodic transfusions about the symptoms that herald the need for transfusion. Likewise, they should be aware of the potential complications of transfusion.

For patient education information, see Anemia and the Anemia Directory.

-

Anemia. Decreased production of red blood cells is suggested in certain patients with anemia. Bone marrow biopsy specimen allows categorization of patients with anemia without evidence of blood loss or hemolysis into 3 groups: aplastic or hypoplastic disorder, hyperplastic disorder, or infiltration disorder. Each category and its associated causes are listed in this image.

-

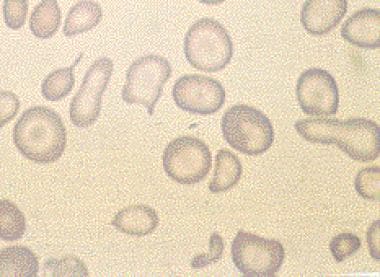

Microcytic anemia.

-

Peripheral smear showing classic spherocytes with loss of central pallor in the erythrocytes.

-

Bone marrow aspirate containing increased numbers of plasma cells.

-

Bone marrow aspirate showing erythroid hyperplasia and many binucleated erythroid precursors.