Witch trials in Virginia

During a 104-year period from 1626 to 1730,[1] there are documented Virginia Witch Trials, hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in Colonial Virginia.[2][3] More than two dozen people are documented having been accused, including two men. Virginia was the first colony to have a formal accusation of witchcraft in 1626, and the first formal witch trial in 1641.[4]

In 1730, Virginia was also the location of the last witchcraft trial in the mainland colonies. Shortly after that, the Parliament of Great Britain repealed the Witchcraft Act 1603, which had sanctioned witchcraft trials for British American colonists.

Witchcraft in Virginia

[edit]

Witchcraft was a phenomenon that was of genuine concern for colonial Virginians. The English settlers brought several superstitions with them to the New World, including their beliefs in the devil’s power, demons, and witches.[5] These beliefs first manifested in the Jamestown colonists’ early views towards the Virginia Indians, whom they believed to be worshippers of the devil.[6]

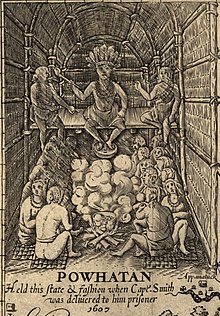

When he described the native peoples of Virginia, English colonist John Smith wrote, “their chief God they worship is the Devil,” and Powhatan, the chief, was “more devil than man.”[7] In 1613, Puritan minister William Crashaw also wrote that "Satan visibly and palpably reigns [in Virginia], more than in any other known place of the world."[8]

Reverend Alexander Whitaker, in a 1613 letter, wrote that the behavior of the native people, “make[s] me think that there be great witches among them, and that they are very familiar with the devil.” Notably, in the same year, Whitaker was responsible for the baptism and conversion of Pocahontas at Henricus.[9]

In the 1620s, some colonists began to accuse one another of practicing witchcraft. Though witchcraft cases in Virginia were less common and the sentences less severe than the more famous witch trials of Salem, documented evidence exists that about two dozen such trials took place in Virginia between 1626 and 1730. These ranged from civil defamation proceedings to criminal accusations.[10] Unlike the Salem witch trial courts, where the accused had to prove their innocence, in Virginia courts the accuser carried the burden of proof.[11] Further, Virginia courts generally ignored evidence said to have been obtained by supernatural means, whereas the New England courts were known to convict people based solely on it. Virginia courts required proof of guilt through searches for "witch's marks" or a ducking test.[11][12]

The southeastern corner of Virginia, around present-day Norfolk and Virginia Beach, saw more accusations of witchcraft than other areas. Researchers believe this may have been due to local poverty as there was no establishment elite to curtail such prosecutions.[11]

The entire history of witchcraft in Virginia is challenging to track, primarily due to the lack of documentation from the accusations and trials. Additionally, many of Virginia's early court records were destroyed in fires during the Civil War.[13]

Prominent figures

[edit]Joan Wright

[edit]The earliest witchcraft allegation on record against an English settler in any British North American colony was made in Virginia in September 1626. “Goodwife” Joan Wright was a midwife in Surry County and the first person in any of the colonies to be legally accused of witchcraft.[14] Wright was a self-professed healer and described as a "cunning" woman, the term used for those who practiced "low-level" or "folk" magic. She was also left-handed, which deemed her untrustworthy and suspicious by the day's standards.[15] Her accusers claimed that she had cursed their local livestock and crops, accurately predicted the deaths of several of her neighbors, and cast a spell that caused the death of a newborn baby.[16] Wright was acquitted despite her admission that she did possess basic knowledge of witchcraft practices.[17]

Katherine Grady

[edit]In 1654, Katherine Grady, en route to Virginia from England, was accused of being a witch, tried, found guilty, and hanged aboard an English ship. Grady was executed before arriving on Virginia's shores, so she is not formally considered a casualty of the Virginia Witch Trials.[18] The matter concerning Grady's execution was later heard in a Jamestown court, and the captain of the ship, Captain Bennet, was tried in the case. The records about the outcome of the case have been lost.[19]

William Harding

[edit]While the vast majority of those accused of witchcraft in Virginia and other colonies were women, a small number of men did come under similar suspicion for using witchcraft and dark magic. In 1656, Reverend David Lindsay accused another Northumberland County resident, William Harding, of witchcraft. Harding was found guilty of the charges, sentenced to 13 whip lashes, and ordered to leave the county. His case remains one of the few male witchcraft trials in the New World.[13]

Grace Sherwood

[edit]The most notable witch trial that occurred in colonial Virginia is the case of Grace Sherwood of Princess Anne County, the only Virginia woman to have ever been found guilty of witchcraft. In 1698, her neighbors first accused Sherwood of having “bewitched their pigs to death and bewitched their Cotton [crop]”. She was also accused of shape-shifting and flying. Sherwood and her husband brought defamation suits against the accusers but did not win either case. The accusations against Sherwood continued until 1706 when Sherwood stood trial before the General Court of Virginia. After a lengthy investigation, the justices decided to use the water test to determine Sherwood's guilt or innocence. The test involved binding her hands and feet and throwing her into a body of water. According to custom, it was believed that as water was considered pure, it would reject witches, causing them to float, whereas the innocent would sink. Sherwood floated, was convicted of witchcraft, and was subsequently imprisoned.[20]

By 1714, Sherwood had been released, demonstrating Virginia authorities' reluctance to execute individuals convicted of witchcraft. English law prescribed severe punishments for witchcraft, the most extreme being execution, referred to as “pains of death,” but no person accused of the crime in colonial Virginia was ever executed.[21]

End of the trials

[edit]According to available records, the last witch trial in Virginia was held in 1730. In the case, Justices charged the accused, a woman named Mary (surname unknown), with using witchcraft to find lost items and treasures. She was convicted and sentenced to be whipped 39 times, but no further documented case details have been found. This was likely the last criminal case of witchcraft in any mainland colonies.[8]

That same year, Benjamin Franklin published a satirical report of a witch trial[22] in the Pennsylvania Gazette, which signaled a shift in the public's perception and acceptance of witchcraft, and embraced Deism, a form of religious belief that emphasized reason and rejected the supernatural.[13]

Virginia's witchcraft cases fell into relative obscurity in the succeeding years and largely out of public memory. The more fanaticized cases overshadowed Virginia's witch trials in Salem and other New England colonies and many Virginians seemingly forgot their witch trials history. In 1849, U.S. Congressman Henry Bedinger of Virginia inaccurately invoked the Salem witch trials as evidence of the Northern states' immorality, stating, “There are some monstrosities we [would] never commit.”[13]

Legacy

[edit]

In 2006, Governor of Virginia Tim Kaine informally pardoned Grace Sherwood 300 years after her conviction. Mayor of Virginia Beach Meyera Oberndorf subsequently declared July 10 to be known as Grace Sherwood Day.[23][24]

In Pungo, Virginia, Sherwood is an honorary official of the neighborhood's annual strawberry festival.[20] A statue depicting Sherwood was erected in 2007 near Sentara Independence in Virginia Beach, close to the site of the colonial courthouse where she was tried.[8]

A Virginia Department of Historic Resources highway marker was erected in 2002 near Sherwood's statue. The location of her water test and the adjacent land are named Witch Duck Bay and Witch Duck Point. Virginia Beach has municipal streets and trails named Sherwood Lane, Witch Point Trail, and Witchduck Road in the area close to where the 1706 water test occurred, now known as Witch Dutch Bay. Many things are named "Witchduck" or "Witch Duck" in Virginia Beach and both spellings are used.[25]

At Colonial Williamsburg, there is a yearly reenactment of the witch trial of Sherwood and a "Cry Witch" historical program. There is also a yearly reenactment held at the Ferry Plantation House in Virginia Beach, as well as a commemorative plaque on the grounds.[26]

The Herb Garden at Old Donation Episcopal Church contains a stone memorial to Sherwood, which was dedicated in 2014.[27]

An obelisk marker commemorating the life of Katherine Grady has been erected by the Winchester Witches project.[19]

A Virginia witch trial loosely based on the story of Joan Wright is featured in a 2017 episode of the British drama television series Jamestown.[28]

In 2019, an original play, "Season of the Witch" premiered at the Jamestown Settlement. The play is a dramatic retelling of the witch trials in Virginia, with a focus on the story of Wright.[14]

See also

[edit]- List of people executed for witchcraft

- Modern witch-hunts

- Witchcraft accusations against children

- Witch trials in the early modern period

- Grace Sherwood

General

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Johnson, Olin (2017-10-26). "There Be Great Witches Among Them: Witchcraft and the Devil in Colonial Virginia". The UncommonWealth. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ admin (2018-02-11). "Historian Explores Witchcraft in Virginia". Chesapeake Bay Magazine. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ "Witchcraft | Department of History". history.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ B., Bell, James (2013). Empire, Religion and Revolution in Early Virginia, 1607-1786. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-32792-5. OCLC 1116059032.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Davis, Richard Beale. “The Devil in Virginia in the Seventeenth Century.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 65 (April 1957): 131–149.

- ^ Sheehan, Bernard W. (1980). Savagism and civility : Indians and Englishmen in Colonial Virginia. Cambridge, UK. ISBN 0-521-22927-8. OCLC 5239471.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Castillo, Susan P. (2005). Colonial encounters in New World writing, 1500-1786 : performing America. Abingdon, Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-56932-0. OCLC 1086549380.

- ^ a b c Witkowski, Monica C. "Witchcraft in Colonial Virginia". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ Snyder, Howard A. (2015-10-29). Jesus and Pocahontas. The Lutterworth Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1cg4mj0. ISBN 978-0-7188-4445-5.

- ^ "Witchcraft in Colonial Virginia". www.colonialwilliamsburg.org. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ a b c Newman, Lindsey M. (April 3, 2009). Under an Ill Tongue: Witchcraft and Religion in Seventeenth-Century Virginia (PDF) (MA (History) thesis). Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- ^ Gibson, Marion. Witchcraft Myths in American Culture. New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Hudson Jr., Carson O. Witchcraft in Colonial Virginia. The History Press. 2019. ISBN 978-1-4671-4424-7

- ^ a b "Witchcraft and gossip: Jamestown Settlement explores English women's interactions with the law in colonial era". Daily Press. 10 September 2019. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ Davis, Richard Beale (April 1979). "The Devil in Virginia in the Seventeenth Century". The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Richmond, VA: Virginia Historical Society. 65 (2): 131–47.

- ^ General Court. General Court Hears Case on Witchcraft (1626). (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/general-court-hears-case-on-witchcraft-1626 .

- ^ Court, General. "General Court Hears Case on Witchcraft (1626)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ "'Witches' in Colonial Virginia: Author to discuss book". The Virginian-Pilot. 28 February 2020. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ a b "Winchester Witches - Katherine Grady". www.winchesterwitches.com. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ a b Witkowski, Monica C. "Grace Sherwood (ca. 1660–1740)". Encyclopedia Virginia. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ Westbury, Susan; Billings, Warren M.; Selby, John E.; Tate, Thad W. (1987). "Colonial Virginia: A History". The Journal of Southern History. 53 (4): 649. doi:10.2307/2208781. ISSN 0022-4642. JSTOR 2208781.

- ^ "Founders Online: A Witch Trial at Mount Holly, 22 October 1730". founders.archives.gov. Retrieved 2022-10-24.

- ^ "Convicted witch pardoned 300 years after trial". NBC News. 11 July 2006. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ "16 Things to Know About... Tim Kaine". Washington Week. 2016-07-20. Archived from the original on July 26, 2016. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ Dunphy, Janet (August 13, 1994). "Rural Charm Meets City Splendor". The Virginian-Pilot. Landmark Communications.

- ^ "USATODAY.com - Va. woman seeks to clear Witch of Pungo". usatoday30.usatoday.com. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ claude.bing (2009-06-04). "The Haunting of Witchduck Road". Virginia Beach. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

- ^ "Meet Real Women From Jamestown's History". Org. 2019-06-27. Retrieved 2022-10-23.

Further reading

[edit]- Hudson Jr., Carson O. Witchcraft in Colonial Virginia. The History Press. 2019. ISBN 978-1-4671-4424-7