Vladimir Kryuchkov

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (December 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Vladimir Kryuchkov | |

|---|---|

Владимир Крючков | |

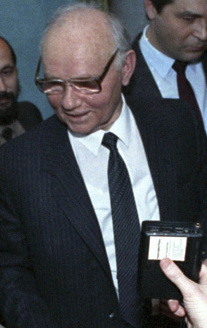

Kryuchkov in 1990 | |

| 7th Chairman of the Committee for State Security (KGB) | |

| In office 1 October 1988 – 28 August 1991 | |

| Premier | Nikolai Ryzhkov Valentin Pavlov |

| Preceded by | Viktor Chebrikov |

| Succeeded by | Vadim Bakatin |

| Full member of the 27th Politburo | |

| In office 20 September 1989 – 14 July 1990 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 29 February 1924 Tsaritsyn, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (now Volgograd, Russia) |

| Died | 23 November 2007 (aged 83) Moscow, Russia |

| Nationality | Soviet and Russian |

| Political party | CPSU (1944–1991) |

Vladimir Aleksandrovich Kryuchkov (Russian: Влади́мир Алекса́ндрович Крючко́в; 29 February 1924 – 23 November 2007) was a Soviet lawyer, diplomat, and head of the KGB, member of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU.

Initially working in the Soviet justice system as a prosecutor's assistant, Kryuchkov then graduated from the Diplomatic Academy of the Soviet Foreign Ministry and became a diplomat. During his years in the foreign service, he met Yuri Andropov, who became his main patron. From 1974 until 1988, Kryuchkov headed the foreign intelligence branch of the KGB, the First Chief Directorate (PGU). During these years, the Directorate was involved in funding and supporting various communist, socialist, and anti-colonial movements across the world, some of which came to power in their countries and established pro-Soviet governments; in addition, under Kryuchkov's leadership the Directorate had major triumphs in penetrating Western intelligence agencies, acquiring valuable scientific and technical intelligence and perfecting the techniques of disinformation and active measures.[1] At the same time, during his tenure the Directorate became plagued with defectors and had the major responsibility for encouraging the Soviet government to invade Afghanistan, and its ability to influence Western European communist parties diminished even further.[1]

From 1988 until 1991, Kryuchkov served as the 7th Chairman of the KGB. He was the leader of the abortive August coup and its governing committee.

Early life and career

[edit]Kryuchkov was born in February 1924 in Tsaritsyn (later called Stalingrad, now Volgograd),[2] to a working-class family. His parents were strong supporters of Joseph Stalin. He joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1944 and became a full-time employee of the Communist Youth League (Komsomol). After earning a law degree, Kryuchkov embarked on a career in the Soviet justice system, working as an investigator for the prosecutor's office in his home city of Stalingrad.[3]

Diplomatic service

[edit]Kryuchkov then[when?] joined the Soviet diplomatic service, stationed in Hungary until 1959. He next worked for the Communist Party Central Committee for eight years, before joining the KGB in 1967 together with his patron Yuri Andropov. He was appointed head of the First Chief Directorate in the summer of 1971, upon the order of Andropov, and deputy chairman in 1978.[according to whom?] In June 1978, he traveled to Afghanistan, and in July 1978 became the KGB rezident in Kabul where he took a very active part in the overthrow of its government at the beginning of the Soviet–Afghan War.[4] In 1988, he was promoted to the rank of General of the Army and became KGB Chairman.[5] In 1989–1990, he was a member of the Politburo.[citation needed]

A political hard-liner, Kryuchkov was among the members of the Soviet intelligence community who misinterpreted the 1983 NATO exercise Able Archer 83 as a prelude to a pre-emptive nuclear strike. Many historians, such as Robert Cowley and John Lewis Gaddis, believe the Able Archer incident was the closest the world has come to nuclear war since the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.[citation needed]

KGB chairmanship

[edit]After KGB Chairman Viktor Chebrikov sided with General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev's rival Yegor Ligachyov in opposition to glasnost and perestroika, he was replaced by Kryuchkov in October 1988.[6] Kryuchkov also opposed Gorbachev's reforms, and in his memoirs defended Stalinism and condemned most reforms to the Soviet political system since the rule of Nikita Khrushchev. His appointment by Gorbachev despite this was because he had specialized primarily in foreign intelligence rather than domestic services. Kryuchkov had also been recommended by Gorbachev's predecessor and mentor Andropov and his reformist colleague Alexander Yakovlev.[7]

After the 1990 Soviet constitutional reforms, Kryuchkov began working with other hardline officials in the new presidential cabinet such as Boris Pugo, Valentin Pavlov, and Gennady Yanayev to undermine Gorbachev's rule.[8] This group of eight ministers eventually became the State Committee on the State of Emergency (GKChP). [citation needed]

Gorbachev attempted to appease Kryuchkov with a presidential decree expanding the powers of the KGB, and ordered him to keep the anti-Communist RSFSR President Boris Yeltsin and the dissident leader Andrei Sakharov under surveillance.[9][10][11] Kryuchkov's intelligence may have deceived Gorbachev into underestimating the risk to his rule and distancing himself in favor of his old reformist colleagues in favor of the hardliners.[12][clarification needed]

According to Sergei Tretyakov, Kryuchkov secretly sent US$50 billion worth of Communist Party funds to an unknown location in the lead up to the collapse of the Soviet Union.[13]

August Coup

[edit]Kryuchkov's strategy eventually shifted to a coup d'état in which a state of emergency would enable the KGB to restore the Soviet Union's hardline Communist political system.[14][15]

During the August coup of 1991, Kryuchkov was the initiator of creation of the GKChP which arrested President Gorbachev. However, the coup failed because of the indecisiveness of Kryuchkov and the other conspirators. Kryuchkov notably mobilized the Alpha Group to arrest Yeltsin but then refused to give it the order to do so.[16] Kryuchkov had also allowed the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic to assume control of domestic KGB activity under its jurisdiction after Chairman Yeltsin's Declaration of State Sovereignty of Russia. Many Russian KGB agents had demonstrated their loyalty to the new government by defying Kryuchkov's order to vote against Yeltsin in the 1991 Russian presidential election.[17] After the defeat of the committee, Kryuchkov was imprisoned for his participation. Kryuchkov was replaced as chairman of the KGB by Vadim Bakatin, released on recognizance not to leave in January 1993.[18]

Many analysts of the Soviet Union at the time and since, including former U.S. Ambassador Jack F. Matlock Jr., have held that Kryuchkov was inadvertently responsible for the collapse of the Soviet Union by staging the coup and destroying the Communist Party's authority. Matlock wrote in his memoir "People do make a difference, and Vladimir Kryuchkov made a big difference. The Soviet Union might exist in some modified form today if another person had been running the KGB in 1990 and 1991."[19][7]

Immediately after the collapse of the coup Kryuchkov unsuccessfully requested a pardon for himself and his co-conspirators on the basis of their old age.[7] On 3 July 1992, Kryuchkov appealed to Russian president Boris Yeltsin,[20] accusing him of laying the blame for the dissolution of the Soviet Union on members of the State Committee on the State of Emergency.[21] Kryuchkov was finally freed in 1994 with a pardon by the State Duma. He subsequently returned to public life with writings condemning Gorbachev's rule. His writings improved his reputation with the Russian public, with a 2007 Levada Center poll revealing that only 12 percent of respondents would have actively opposed his coup.[7] On 7 May 2000, Kryuchkov attended the first inauguration of Vladimir Putin as President of Russia.[22]

Family

[edit]His son was a resident of Switzerland in the 1990s where very large sums were transiting during the 1990s looting of Russia. Yevgeny Primakov blocked the Duma's Ponomarev investigative commission from accessing KGB, FCD, and SVR documents.[23]

Death

[edit]Kryuchkov died at the age of 83 on 23 November 2007.[5] His body was buried at the Troyekurovskoye Cemetery in Moscow.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Robert W Pringle, Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence Kryuchkov, Vladimir

- ^ "Soviet Union's hawkish KGB chief Kryuchkov dies at 83". Reuters. 25 November 2007.

- ^ Gale Encyclopedia of Russian History: Vladimir Alexandrovich Kryuchkov

- ^ Млечин, Леонид Михайлович (Mlechin, Leonid Mikhailovich) (2004). Служба внешней разведки [Foreign Intelligence Service] (in Russian). Moscow: Eksmo. ISBN 5-699-08094-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Levy, Clifford J. (26 November 2007). "Vladimir Kryuchkov, 83, Ex-Chief of K.G.B." The New York Times. p. 21.

- ^ Marples, David R. (2004). The Collapse of the Soviet Union: 1985-1991 (1 ed.). Harlow, England: Pearson. pp. 12–16. hdl:2027/mdp.39015059113335. ISBN 1-4058-9857-7. OCLC 607381176.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Archie (30 November 2007). "Obituary: Vladimir Kryuchkov". the Guardian. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Marples 2004, p. 71.

- ^ Kyriakodis, Harry G. (1991). "The 1991 Soviet and 1917 Bolshewk Coups Compared: Causes, Consequences and Legality". Russian History. 18 (1–4): 323–328. doi:10.1163/187633191X00137. ISSN 0094-288X.

- ^ Marples (2004), p. 83

- ^ Marples (2004), p. 123

- ^ Marples 2004, p. 105.

- ^ Wise, David (27 January 2008). "Spy vs. Spy". The Washington Post. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- ^ Dunlop, John B. (1995). The rise of Russia and the fall of the Soviet empire (1st pbk. printing, with new postscript ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2100-6. OCLC 761105926. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ Dunlop, John B. (1995). The rise of Russia and the fall of the Soviet empire (1st pbk. printing, with new postscript ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-2100-6. OCLC 761105926. Archived from the original on 4 December 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- ^ "Hardline coup set the stage for Soviet collapse 30 years ago". AP NEWS. 18 August 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ^ Azrael, Jeremy R.; Rahr, Alexander G. (1993). The Formation and Development of the Russian KGB, 1991-1994 (PDF) (1 ed.). Santa Monica, California: National Defense Research Institute. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0-8330-1491-9.

- ^ "Press-konferentsiya po delu GKCHP" Пресс-конференция по делу ГКЧП [Press Conference on the GKChP Case]. Kommersant (in Russian). No. 13. 27 January 1993. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Marples 2004, p. 135.

- ^ "Biografiya Vladimira Kryuchkova: sotrudnichayet s Luzhkovym" Биография Владимира Крючкова: сотрудничает с Лужковым [Biography of Vladimir Kryuchkov: In Collaboration with Luzhkov]. Temadnya (in Russian). Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ "Kryuchkov Vladimir Aleksandrovich" Крючков Владимир Александрович [Kryuchkov Vladimir Aleksandrovich]. Biografija (in Russian). Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Gessen, Masha (2012). The man without a face : the unlikely rise of Vladimir Putin. Internet Archive. New York: Riverhead Books. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-59448-842-9.

- ^ Leach, James A., ed. (21 September 1999). Russian Money Laudering: United States Congressional Hearing (serial number 106–38). Diane Publishing. p. 318. ISBN 9780756712556. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Kryuchkov, Vladimir Alexandrovich (1996). Personal Business. Moscow: Olympus. pp. 872.

- 1924 births

- 2007 deaths

- Politicians from Volgograd

- Members of the Central Committee of the 27th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- Members of the Central Committee of the 28th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- Members of the Politburo of the 27th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- Diplomatic Academy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation alumni

- Eleventh convocation members of the Soviet of Nationalities

- Expelled members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

- Kutafin Moscow State Law University alumni

- State Committee on the State of Emergency members

- Recipients of the Medal "For Distinction in Guarding the State Border of the USSR"

- Recipients of the Order of Lenin

- Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner

- Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour

- Army generals (Soviet Union)

- KGB chairmen

- Neo-Stalinists

- People of the Soviet–Afghan War

- Russian communists

- Burials in Troyekurovskoye Cemetery