Timeline of LGBTQ history in the United States

Appearance

This is a timeline of notable events in the history of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) community in the United States.

19th century

[edit]

- 1860: Walt Whitman, considered by many academics to be either gay or bisexual, publishes a cluster of homoerotic poems under the title Calamus.[4]

- 1869: First cross-dressing ball is held at the Hamilton Lodge in Harlem.[5][6]

- 1870: Bayard Taylor publishes the novel Joseph and His Friend: A Story of Pennsylvania, considered by some academics to be the first US gay novel.[7][8] However, other critics have offered alternate interpretations on whether it actually depicts romantic love between men or an idealization of male spirituality.

- 1888: William Dorsey Swann, the first known person to self-identify as "queen of drag", and a group of men are detained in the earliest recorded arrests for female impersonation in the United States.[9][10]

- 1889: British writer and critic Alan Dale publishes in the US the novel A Marriage Below Zero, considered the first US novel that explicitly depicts a homosexual relationship, although it also started the trend of including tragic endings (many times by suicide) for its LGBT characters.[11]

20th century

[edit]1900s

[edit]- 1903: The Ariston Bathhouse raid takes place in New York City, which became the first recorded police raid against an LGBT venue in US history. As a result of the incursion, 26 men were arrested and 12 of them were prosecuted on sodomy charges.[12]

- 1906: American author Edward Prime-Stevenson publishes the novel Imre: A Memorandum in Italy, considered the first American gay novel in which the same-sex couple get a happy ending.[13]

1920s

[edit]1922

[edit]- The American silent movie Manslaughter, directed by Cecil B. DeMille, gets released. The film showed the first erotic same-sex kiss in the history of cinema.[14]

1924

[edit]- The Society for Human Rights, established in Chicago in 1924, was the first recognized gay rights organization in the United States, having received a charter from the state of Illinois, and produced the first American publication for homosexuals, Friendship and Freedom.[15] Society founder Henry Gerber was inspired to create it by the work of German doctor Magnus Hirschfeld and the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. A few months after being chartered, in 1925, the group ceased to exist in the wake of the arrest of several of the society's members. Despite its short existence and small size, the society has been recognized as a precursor to the modern gay liberation movement.

1926

[edit]- June 11: Police raids the lesbian bar Eve's Hangout, located in New York City, and arrests its owner, Polish feminist Eva Kotchever. Kotchever was deported after the incident and Eve's Hangout never opened again.[16]

1929

[edit]- The Surprise of a Knight becomes the first American pornographic film to depict homosexual intercourse.[17]

1930s

[edit]1934

[edit]- The Motion Picture Association starts enforcing the Hays Code, which in practice banned the representation of explicit LGBT characters onscreen, with the exception of those who were depicted as villains or criminals.[18][19]

1940s

[edit]1947

[edit]- June: Lisa Ben (anagram of «lesbian») starts self-publishing in Los Angeles a small lesbian magazine called Vice Versa, considered the oldest recorded lesbian periodical in the United States.[20]

1948

[edit]- Alfred Kinsey, a bisexual American sexologist, publishes his seminal work Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, which helped the homosexual male community gain more visibility.[21] The book states, among other things, that 37% of the male subjects surveyed had at least one homosexual experience,[22] and that 10% of American males surveyed were "more or less exclusively homosexual for at least three years between the ages of 16 and 55".[23]

1950s

[edit]1950

[edit]

- The Mattachine Society, founded in 1950, was one of the earliest LGBT (gay rights) organizations in the United States, probably second only to Chicago's Society for Human Rights. Communist and labor activist Harry Hay formed the group with a collection of male friends in Los Angeles to protect and improve the rights of gay men.

- As part of the Lavender scare, a moral panic about homosexuals working in US federal agencies, the Senate launched an investigation in June 1950 into the government's employment of homosexuals. The results were not released until December, but in the meantime federal job losses due to allegations of homosexuality increased greatly, rising from approximately 5 to 60 per month.[24] To address this supposed threat, Joseph McCarthy hired Roy Cohn – who later died of AIDS and who, like McCarthy himself, is believed to have been a closeted gay man[25][26][27][28] – as chief counsel of his Congressional subcommittee. Together, McCarthy and Cohn were responsible for the firing of scores of gay men and women from government employment, and they strong-armed many opponents into silence using rumors of their homosexuality.[29][30][31]

1951

[edit]- The Black Cat Bar, located in San Francisco's North Beach neighborhood, was the focus of one of the earliest victories of the homophile movement when in 1951 the California Supreme Court affirmed the right of gay people to assemble in a case brought by the heterosexual owner of the bar.

1952

[edit]- April: The American Psychiatric Association includes homosexuality in their diagnostic manual as a "sociopathic personality disturbance".[32]

- Christine Jorgensen was an American transgender woman who was the first person to become widely known in the United States for having sex reassignment surgery. She traveled to Europe and in Copenhagen, Denmark, obtained special permission to undergo a series of operations starting in 1951.[33] Her transition was the subject of a New York Daily News front-page story in 1952.

- American author Patricia Highsmith publishes under the pseudonym «Claire Morgan» the novel The Price of Salt (later republished as Carol), which became a classic of lesbian literature.[34][35]

1953

[edit]- April 27: As a result of the Lavender scare, President Eisenhower issues Executive Order 10450, which banned gay men and lesbians from working for any agency of the federal government.[36] It was not until 1973 that a federal judge ruled that a person's sexual orientation alone could not be the sole reason for termination from federal employment,[37] and not until 1975 that the United States Civil Service Commission announced that they would consider applications by gays and lesbians on a case-by-case basis.[37]

1955

[edit]- The Daughters of Bilitis /bɪˈliːtɪs/, also called the DOB or the Daughters, was the first[38] lesbian civil and political rights organization in the United States. It was formed in San Francisco in 1955.

1956

[edit]- The Daughters of Bilitis starts the publication of The Ladder, considered the first nationally distributed lesbian magazine.[20]

1958

[edit]- The first gay leather bar, the Gold Coast, opened in Chicago in 1958.

- One, Inc. v. Olesen 355 U.S. 371 (1958) is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision for LGBT rights in the United States. It was the first U.S. Supreme Court ruling to deal with homosexuality and the first to address free speech rights with respect to homosexuality. The ruling held that pro-homosexual writing is not per se obscene.

1959

[edit]- The Cooper Donuts Riot happened in 1959 in Los Angeles, when the lesbians, gay men, transgender people, and drag queens who hung out at Cooper Do-nuts and who were frequently harassed by the LAPD fought back after police arrested three people, including John Rechy. Patrons began pelting the police with donuts and coffee cups. The LAPD called for back-up and arrested a number of rioters. Rechy and the other two original detainees were able to escape.[39]

1960s

[edit]1961

[edit]- José Sarria ran for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1961, becoming the first openly gay candidate for public office in the United States.[40] He did not win, however.[41]

- 28 July: Illinois becomes the first state to legalize same-sex consensual sexual activity. The law came into effect on January 1, 1962.[42][32]

- 11 September: The Rejected becomes the first documentary about homosexuality to be broadcast in American television, after it was broadcast by a local TV station in California.[32][43]

1962

[edit]- The first article published in America that recognized a city's gay community and political scene was about Philadelphia, and was titled "The Furtive Fraternity" (1962, by Gaeton Fonzi) and published in Greater Philadelphia.

1964

[edit]- American film The Best Man, directed by Franklin J. Schaffner is released. It is the first US film to use the word "homosexual".[44]

1965

[edit]- In April 150 gender non-conforming people came to Dewey's Coffee Shop in Philadelphia to protest the fact that the shop was refusing to serve young people in "non-conformist clothing".[45] After three protesters refused to leave after being denied service they, along with a black gay activist, were arrested. This led to a picket of the establishment organized by the black LGBTQ population. Later, in May of that same year another sit-in was organized and Dewey's agreed to end their discriminatory policies.[46]

1966

[edit]- The Compton's Cafeteria Riot occurred in August 1966 in the Tenderloin district of San Francisco. This incident was one of the first recorded LGBT-related riots in United States history.[note 1] It marked the beginning of transgender activism in San Francisco.[47]

1967

[edit]- 1 January: The Black Cat Tavern, one of the most well-known gay bars of its time, faces an extreme police raid just after midnight as many of the gay patrons share a New Year's kiss.[48] This raid led to the later protesting against constant police harassment of gay people by hundreds of protestors on February 11 outside the Black Cat Tavern.[49]

- 21 April: New York decided that it could no longer forbid bars from serving gay men and lesbians after activists staged a "Sip-In" at Julius, a bar, on April 21.

- September: The first issue of the magazine The Los Angeles Advocate is published. Two years later it changed its name to The Advocate and began to be distributed nationally. Today it is considered the oldest LGBT magazine still in publication in the country.[50][32]

- 24 November: The first bookstore devoted to gay and lesbian authors was founded by Craig Rodwell on November 24, 1967, as the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop.[51][52] It was initially located at 291 Mercer Street.[53][54][52]

1968

[edit]- 9 May: One of the biggest pre-Stonewall gay rights demonstrations occurs at Bucks County Community College in Newtown, Bucks County, Pennsylvania, when about 200 students protested against the decision made by the college's president to cancel a lecture by Richard Leitsch, president of the Mattachine Society of New York.[55]

1969

[edit]

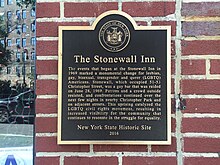

- 28 June – The Stonewall riots (also referred to as the Stonewall uprising or the Stonewall rebellion) were a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations by members of the gay (LGBT) community[note 2] against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. They are widely considered to constitute the most important event leading to the gay liberation movement[56][57][58] and the modern fight for LGBT rights in the United States.[59][60]

- 31 October – Sixty members of the Gay Liberation Front and the Society for Individual Rights staged a protest outside the offices of the San Francisco Examiner in response to a series of news articles disparaging LGBT people in San Francisco's gay bars and clubs.[61][62] The peaceful protest against the "homophobic editorial policies" of the Examiner turned tumultuous and were later called "Friday of the Purple Hand" and "Bloody Friday of the Purple Hand".[62][63][64][65][66] Examiner employees "dumped a bag of printers' ink from the third story window of the newspaper building onto the crowd".[62][64] Some reports state that it was a barrel of ink poured from the roof of the building.[67] The protesters "used the ink to scrawl 'Gay Power' and other slogans on the building walls" and stamp purple hand prints "throughout downtown San Francisco" resulting in "one of the most visible demonstrations of gay power".[62][64][66] According to Larry LittleJohn, then president of SIR, "At that point, the tactical squad arrived – not to get the employees who dumped the ink, but to arrest the demonstrators. Somebody could have been hurt if that ink had gotten into their eyes, but the police were knocking people to the ground."[62] The accounts of police brutality include women being thrown to the ground and protesters' teeth being knocked out.[62][68]

1970s

[edit]1970

[edit]

- The modern gay movement for PRIDE and marriage equality in the United States began on the Minneapolis campus (U of M) of the University of Minnesota.[69] James Michael McConnell, librarian,[70] and Richard John Baker,[71] law student, applied for a marriage license.[72] Gerald R. Nelson, Clerk of District Court, denied the license because both applicants were men.[73]

- 17 March: The film The Boys in the Band, directed by William Friedkin, gets released. The film was one of the first American movies focused on gay characters and is now considered a milestone of queer cinema.[74]

- 28 June: The first Christopher Street Liberation Day parade takes place in New York City, celebrating the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots. Today, it's considered one of the first LGBT pride parades.[32]

1971

[edit]- 4 June – Members of the Gay Activists Alliance demand marriage rights for same-sex couples at New York City's Marriage License Bureau.[75][76]

- Jack Baker and Michael McConnell re-apply and are granted a marriage licence in Blue Earth County, Minnesota after discovering the county has no laws prohibiting same sex marriage. Therefore, on 3, Sept, 1971 both men became the first legally married same sex couple in the U.S. history.

- 15 October –The Minnesota Supreme Court rules in Baker v. Nelson that the state's statute limiting marriage to different-sex couples does not violate the U.S. Constitution. However this ruling did not invalidate the 1971 licence in Blue Earth County.[77] Baker and McConnell appealed the verdict, but the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed the appeal the following year.[78]

1973

[edit]- 1 January – Maryland becomes the first state in the U.S. to statutorily ban same-sex marriage.[79] In the following two decades, other states joined Maryland in statutorily banning same-sex marriage, reaching almost the totality of US states by 1994.

- 24 June – The UpStairs Lounge arson attack occurred on June 24, 1973, at a gay bar located on the second floor of the three-story building at 141 Chartres Street in the French Quarter of New Orleans, Louisiana, in the United States.[80] Thirty-two people died as a result of fire or smoke inhalation. The official cause is still listed as "undetermined origin".[81] The most likely suspect, a gay man named Roger Nunez who had been ejected from the bar earlier in the day, was never charged and took his own life in November 1974.[82][83][84] No evidence has ever been found the arson was motivated by hatred or overt homophobia.[84] Until the 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting, the UpStairs Lounge arson attack was the deadliest known attack on a gay club in U.S. history.

- 9 November: The Kentucky Court of Appeals rules in Jones v. Hallahan that two women were properly denied a marriage license based on dictionary definitions of marriage, despite the fact that state statutes do not restrict marriage to a female-male couple.[85]

- 15 December: The American Psychiatric Association declassified homosexuality as a mental disorder.[86]

1974

[edit]- 2 April – Kathy Kozachenko becomes the first openly LGBT person to be elected to public office in the United States' history. She was elected to the City Council of Ann Arbor, Michigan, and ran under the Human Rights Party.[87]

- 20 May: Singer v. Hara, a lawsuit filed by John F. Singer and Paul Barwick after being refused a request for a marriage license at the King County Administration Building in Seattle, Washington on 20 September 1971, ends with a unanimous rejection by the Washington State Court of Appeals.[88]

1975

[edit]- 14 January: For the first time, a federal LGBT rights bill is introduced to Congress. However, the bill died on committee.[32]

- Gay American Indians, the first gay American Indian liberation organization, was founded.[89]

- Elaine Noble began to serve in the Massachusetts House of Representatives, the first openly gay person elected into a state legislature.[90]

- March 26 – April 22: In Colorado, the Boulder County Clerk, Clela Rorex, issues marriage licenses to 6 same-sex couples after receiving a favorable opinion from an assistant district attorney.[91][92] But when one of those married in Boulder tried to use it to sponsor his husband for immigration purposes, he lost his case, Adams v. Howerton, in federal court.[93]

1976

[edit]

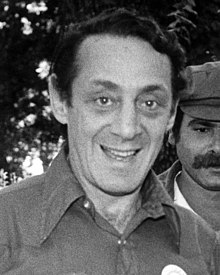

- Harvey Milk became the first openly gay male non-incumbent elected in the United States (and the first openly gay person elected to public office in California), when elected as a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors.[94]

- The Lincoln Legion of Lesbians was established in Nebraska, an early example of a lesbian organization in a rural state.[95]

- Gaysweek was founded as the first mainstream gay publication published by an African-American (Alan Bell).[96][97][98][99]

1977

[edit]- The Supreme Court of New York rules in favor of transgender tennis player Renée Richards, who brought a lawsuit in order to compete in the female category of the US Open.[32]

- November: The 1977 National Women's Conference adopts a resolution which called for an end to discrimination against sexual minorities and to repeal any state law that restricted sexual relationships between adults.[100]

1978

[edit]- Gilbert Baker designs the rainbow flag as a symbol of LGBT pride and hope,[32] for the 1978 San Francisco Gay Freedom Celebration.

- The San Francisco Lesbian/Gay Freedom Band was founded by Jon Reed Sims in 1978 as the San Francisco Gay Freedom Day Marching Band and Twirling Corp. Upon its founding in 1978, it became the first openly gay musical group in the world.

- November 27: Harvey Milk, the first openly gay male non-incumbent elected in the United States (and the first openly gay person elected to public office in California), is assassinated by Dan White.[94]

1979

[edit]- 21 May; The White Night riots were a series of violent events sparked by an announcement of the lenient sentencing of Dan White for the assassinations of San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and of Harvey Milk, a member of the city's Board of Supervisors who was the first openly gay male non-incumbent elected in the United States (and the first openly gay person elected to public office in California). The events took place on the night of May 21, 1979 (the night before what would have been Milk's 49th birthday) in San Francisco. Earlier that day, White had been convicted of voluntary manslaughter, the lightest possible conviction for his actions. As well, the gay community of San Francisco had a longstanding conflict with the San Francisco Police Department. White's status as a former police officer intensified the community's anger at the SFPD. Initial demonstrations took place as a peaceful march through the Castro district of San Francisco. After the crowd arrived at the San Francisco City Hall, violence began. The events caused hundreds of thousands of dollars' worth of property damage to City Hall and the surrounding area, as well as injuries to police officers and rioters. Several hours after the riot had been broken up, police made a retaliatory raid on a gay bar in San Francisco's Castro District. Many patrons were beaten by police in riot gear. Two dozen arrests were made during the course of the raid, and several people later sued the SFPD. In the following days, gay leaders refused to apologize for the events of that night. This led to increased political power in the gay community, which culminated in the election of Mayor Dianne Feinstein to a full term the following November. In response to a campaign promise, Feinstein appointed a pro-gay Chief of Police, which increased recruitment of gay people in the police force and eased tensions. The SFPD never apologized for its indiscriminate attacks on the gay community.

- 14 October: The first National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights takes place in Washington D.C., with an attendance between 75,000 and 125,000 people.[32]

1980s

[edit]1980

[edit]- Transgender people were officially classified by the American Psychiatric Association as having "gender identity disorder."[101]

1982

[edit]- February 25 — Wisconsin becomes the first state in the nation to make it unlawful for private businesses to discriminate based on sexual orientation in employment and housing. Gay activist Leon Rouse is a leader in getting the legislation passed.[102]

1983

[edit]

- Gerry Studds became the first openly gay member of Congress when he came out in 1983.[103]

1984

[edit]- 4 December: The Berkeley City Council passes a domestic partnership policy to offer insurance benefits to city employees in same-sex relationships, which made Berkeley the first city in the U.S. to do so. Among the people who fought for the approval of the policy was Tom Brougham, a Berkeley city employee who coined the term "domestic partner" and created the concept in a letter sent to the Berkeley City Council a few years earlier.[104]

1985

[edit]- 25 March: West Hollywood becomes the first US city to enact a domestic partnership registry open to all its citizens.[105][106]

1986

[edit]- Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986), is a United States Supreme Court decision that upheld, in a 5–4 ruling, the constitutionality of a Georgia sodomy law criminalizing oral and anal sex in private between consenting adults, in this case with respect to homosexual sodomy, though the law did not differentiate between homosexual sodomy and heterosexual sodomy.[107] This case was overturned in 2003 by a case styled Lawrence v. Texas.

1987

[edit]- Barney Frank became the first member of Congress to voluntarily identify themselves as gay.[108]

1989

[edit]- 30 May: San Francisco Board of Supervisors passes a domestic partnership registry ordinance,[109][110] which is closely defeated by San Francisco voters as Proposition S on 7 November.[111][112]

- The rainbow flag came to nationwide attention in the United States after John Stout sued his landlords and won when they attempted to prohibit him from displaying the flag from his West Hollywood, California, apartment balcony.[113]

1990s

[edit]1990

[edit]- A modified domestic partnership registry ordinance is passed by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors,[112] and the ordinance is ratified by voters as Proposition K on 6 November.

1991

[edit]- June: Berkeley becomes the third city in California to create a domestic partnership registry for same- and opposite-sex couples.

- December 17: The Minnesota Court of Appeals issues a ruling in the case In re Guardianship of Kowalski in which it gave the legal guardianship of an incapacitated woman to her lesbian partner.[114]

1993

[edit]- 5 May: The Supreme Court of Hawaii sends the case of Baehr v. Miike to a trial court after ruling that the state same-sex marriage ban was presumed to be unconstitutional and that the State would need to demonstrate a compelling interest in denying same-sex couples the right to marry.[115][116]

- Brandon Teena was an American transgender man who was raped and murdered in Humboldt, Nebraska in 1993.[note 3][117][118] His life and death were the subject of the Academy Award-winning 1999 film Boys Don't Cry, which was partially based on the 1998 documentary film The Brandon Teena Story. Both films also illustrated that legal and medical discrimination contributed to Teena's violent death.[119] Teena's murder, along with that of Matthew Shepard, led to increased lobbying for hate crime laws in the United States.[120][121]

- 30 November: President Bill Clinton signs a military policy known as "Don't ask, don't tell", which took effect on February 24, 1994. The policy prohibited military personnel from discriminating against or harassing closeted gay or bisexual service members or applicants, while barring openly gay, lesbian, or bisexual persons from military service.[122][32]

1994

[edit]- "Don't ask, don't tell" was the official United States policy on military service by gays, bisexuals, and lesbians, instituted by the Clinton Administration on February 28, 1994, when Department of Defense Directive 1304.26 issued on December 21, 1993, took effect,

- 21 March: Philadelphia, a film about a gay man who is dying of complications related to AIDS, wins two Oscars at the 66th Academy Awards.[32]

- September: Governor Pete Wilson from California vetoes a bill that would have legalized domestic partnerships in the state.[123]

1996

[edit]- April: Rent, a musical written by Jonathan Larson about a group of friends during the AIDS crisis and now considered a queer musical classic, is performed for the first time.[124]

- 20 May: Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996),[125] is a landmark Supreme Court of the United States case dealing with sexual orientation and state laws. It was the first Supreme Court case to address gay rights since Bowers v. Hardwick (1986),[126] when the Court had held that laws criminalizing sodomy were constitutional.[127] The Court ruled in a 6–3 decision that a state constitutional amendment in Colorado preventing protected status based upon homosexuality or bisexuality did not satisfy the Equal Protection Clause.[125] The majority opinion in Romer stated that the amendment lacked "a rational relationship to legitimate state interests", and the dissent stated that the majority "evidently agrees that 'rational basis'—the normal test for compliance with the Equal Protection Clause—is the governing standard".[125][128] The state constitutional amendment failed rational basis review.[129][130][131][132]

- 21 September: As a direct result of the Baehr v. Lewin ruling of 1993, President Bill Clinton signs the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) into law, which banned the federal Government from recognizing same-sex unions.[133]

- 3 December: Judge Kevin Chang of Hawaii issues a ruling in Baehr v. Lewin (now named Baehr v. Miike) in which he declares that the state hadn't established any compelling interest to motivate denying same-sex couples the right to marry and that they should be issued marriage licenses. However, he stayed his ruling pending appeal.[134]

1997

[edit]- April: Comedian and TV actress Ellen DeGeneres comes out as lesbian in the cover of Time magazine.[32]

- April 30: The character Ellen Morgan, interpreted by Ellen DeGeneres, becomes the first protagonist of an American primetime network TV show to come out of the closet.[32]

- As a direct result of the Baehr v. Miike ruling, Hawaii passes a law to establish Reciprocal beneficiary relationships, which made Hawaii the first state in the country to offer statewide recognition for same-sex couples.[135]

1998

[edit]- Tammy Baldwin becomes the first openly gay person elected to the House of Representatives, and the first open lesbian elected to Congress.[136][137]

- Matthew Shepard was a gay American student at the University of Wyoming who was beaten, tortured, and left to die near Laramie on the night of October 6, 1998.[138] He was taken to Poudre Valley Hospital in Fort Collins, Colorado, where he died six days later from severe head injuries. Perpetrators Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson were arrested shortly after the attack and charged with first-degree murder following Shepard's death. Significant media coverage was given to the killing and to what role Shepard's sexual orientation played as a motive in the commission of the crime. Both McKinney and Henderson were convicted of the murder, and each received two consecutive life sentences. Shepard's murder, along with that of Brandon Teena, led to increased lobbying for hate crime laws in the United States.[120][121]

- Rita Hester was a transgender African American woman who was murdered in Allston, Massachusetts in 1998.[139] In response to her murder, an outpouring of grief and anger led to a candlelight vigil held the following Friday (December 4) in which about 250 people participated. The community struggle to see Rita's life and identity covered respectfully by local papers, including the Boston Herald and Bay Windows, was chronicled by Nancy Nangeroni.[140] Her death also inspired the "Remembering Our Dead" web project and the Transgender Day of Remembrance.[141]

- 3 November: Hawaii and Alaska become the first U.S. states to pass constitutional amendments against same-sex marriage.[142] As a result of this, the ruling in Baehr v. Miike was reversed. Other U.S. states followed suit and passed similar amendments in the following years, reaching a peak of 31 in 2012. For more information, refer to U.S. state constitutional amendments banning same-sex unions.

1999

[edit]- The Transgender Pride Flag was created by American transgender woman Monica Helms in 1999.[143][144]

- Transgender Day of Remembrance was founded in 1999 by Gwendolyn Ann Smith, a transgender woman,[145] to memorialize the murder of transgender woman Rita Hester in Allston, Massachusetts.[146] Since its inception, TDoR has been held annually on November 20,[147] and it has slowly evolved from the web-based project started by Smith into an international day of action. It is now observed annually on November 20 as a day to memorialize all those who have been murdered as a result of transphobia[148] and to draw attention to the continued violence endured by the transgender community.[149]

- 22 September: Governor Gray Davis from California signs a domestic partnerships bill into law that provided limited rights for same-sex couples,[150] which made California the first state to have a statewide domestic partnership scheme and the second to provide a registry for same-sex couples after Hawaii.

- 20 December: The Vermont Supreme Court holds in Baker v. Vermont that excluding same-sex couples from marriage violates the Vermont Constitution and orders the legislature to establish same-sex marriage or an equivalent status.[151]

21st century

[edit]2000s

[edit]2000

[edit]- 26 April: Governor Howard Dean from Vermont signs a civil unions bill in response to the ruling of Baker v. Vermont, thus making Vermont the first state in the U.S. to give civil union rights to same-sex couples. It became law on 1 July.[152][153][154]

- The Transgender Pride Flag was first shown, at a pride parade in Phoenix, Arizona, United States in 2000.[155]

2002

[edit]- Gwen Araujo was an American transgender teenager who was murdered in Newark, California in 2002.[156] She was killed by four men, two of whom she had been sexually intimate with, who beat and strangled her after discovering that she was transgender.[157][158] Two of the defendants were convicted of second-degree murder,[159] but not convicted on the requested hate crime enhancements. The other two defendants pleaded guilty or no contest to voluntary manslaughter. In at least one of the trials, a "trans panic defense"—an extension of the gay panic defense—was employed.[159][160] Some contemporary news reports referred to her by her birth name.

2003

[edit]- Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003)[161] is a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court. The Court struck down the sodomy law in Texas in a 6–3 decision and, by extension, invalidated sodomy laws in 13 other states, making same-sex sexual activity legal in every U.S. state and territory. The Court, with a five-justice majority, overturned its previous ruling on the same issue in the 1986 case Bowers v. Hardwick, where it upheld a challenged Georgia statute and did not find a constitutional protection of sexual privacy.

- 18 November: The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts rules in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health that same-sex couples have the right to marry, setting the start date for the ruling to take effect on 17 May 2004, to allow the legislature six months to modify state law if it chooses to.[162]

2004

[edit]- Registered partnerships are legalized in New Jersey (12 January) and Maine (April).[163]

- February/March: A number of U.S. jurisdictions begin issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples, including San Francisco, California (12 February), Sandoval County, New Mexico (20 February), New Paltz, New York (27 February), Multnomah County, Oregon (3 March) and Asbury Park, New Jersey (9 March). The licenses were later nullified (not necessarily in Sandoval County, New Mexico).

- 17 May: Same-sex marriage becomes legal in Massachusetts after the legislature failed to take any action in the 180 days period given by the state's Supreme Court. It became the first U.S. state to legalize same-sex marriage.[164]

- 2 November: Voters in Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Michigan, Mississippi, Montana, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Utah approve state constitutional amendments defining marriage as the union of one man and one woman.[165]

2005

[edit]- 20 April: Governor Jodi Rell from the U.S. State of Connecticut signs a same-sex civil unions bill into law. It came into effect on 1 October.

- 12 May: U.S. District Judge Joseph Bataillon rules in Citizens for Equal Protection v. Bruning that a constitutional amendment to the Nebraska Constitution that denies recognition of same-sex couples under any designation violates the U.S. Constitution.[166] (His decision is overruled in 2006 by the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals.)[167]

- 6 September: California becomes the first state to pass a same-sex marriage law by its legislature.[32] However, Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed the law.[168]

- GLBT History Museum of Central Florida was founded.[169]

2006

[edit]- 5 March: Brokeback Mountain, an LGBT drama film directed by Ang Lee, wins three Oscars at the 78th Academy Awards. Although it was the favorite to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, it was beaten by Crash in a decision now considered infamous.[170]

- 25 October: The New Jersey Supreme Court holds unanimously in Lewis v. Harris that excluding same-sex couples from marriage violates the state constitution's guarantee of equal protection. A majority of four justices gives the state legislature six months to amend the state's marriage laws or create civil unions.[171]

- 21 December: Governor Jon Corzine from New Jersey signs a bill legalizing civil unions into law.[172] It took effect on 19 February 2007.

2007

[edit]- Domestic partnerships are legalized in Washington (21 April)[173] and Oregon (9 May).

- May 31: Governor John Lynch from New Hampshire signs a civil unions bill into law. It came into effect on 1 January 2008.

- August 30: A court of Iowa strikes down its ban on same-sex marriage as a result of a legal challenge. About 20 couples obtained marriage licenses and one couple married before the judge issued a stay of his ruling pending appeal.[174]

2008

[edit]

- 15 May: The Supreme Court of California legalizes same-sex marriage in its ruling of In re Marriage Cases.[175] Marriages begin on June 17.[176]

- 22 May: Domestic partnerships are legalized in Maryland.

- 22-year-old Lateisha Green, a trans woman, was shot and killed by Dwight DeLee in Syracuse, NY because he thought she was gay.[177] Local news media reported the incident with her legal name, Moses "Teish" Cannon.[178] DeLee was convicted of first-degree manslaughter as a hate crime on July 17, 2009, and received the maximum sentence of 25 years in state prison. This was only the second time in the nation's history that a person was prosecuted for a hate crime against a transgender person and the first hate crime conviction in New York state.[179][180][181]

- Angie Zapata was an American transgender woman beaten to death in Greeley, Colorado in 2008. Her killer, Allen Andrade, was convicted of first-degree murder and committing a hate crime, because he murdered her after learning she was transgender. The case was the first in the nation to get a conviction for a hate crime involving a transgender victim, which occurred in 2009.[182] Angie Zapata's story and murder were featured on Univision's November 1, 2009 Aquí y Ahora television show.

- 10 October: The Supreme Court of Connecticut legalizes same-sex marriage in the landmark Kerrigan v. Commissioner of Public Health ruling.[183] Same-sex weddings started on 12 November.

- 4 November: A referendum seeking to constitutionally ban same-sex marriages in California is approved by 52.2% of voters;[184] thus overturning same-sex marriage in California, this event being noteworthy because it was the first time in modern history that same-sex marriage has been overturned.

2009

[edit]- 3 April: The Iowa Supreme Court, ruling in Varnum v. Brien, holds that the state's restriction of marriage to different-sex couples violates the equal protection clause of the Iowa Constitution.[185] All three of the states that had legalized same-sex marriage at this point—Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Iowa—had done so by court ruling.[186]

- 7 April: Vermont legalizes same-sex marriage after overriding Governor Jim Douglas, who had vetoed the law a day earlier, thus making Vermont the first U.S. state to legalize same-sex marriage through statute.[187] The bill came into effect on 1 September.

- 6 May: Governor John Baldacci from Maine signs a same-sex marriage bill into law.[188] However, opponents organized a referendum that overturned it on 3 November.[189]

- 18 May: Governor Chris Gregoire from Washington signs a so-called "everything-but-marriage" registered partnerships bill into law.[190][191] Opponents organized a referendum that failed to overturn it on 3 November.[192]

- 31 May: The Assembly of Nevada legalizes domestic partnerships by overriding a veto from Governor Jim Gibbons.[193][194] The law came into effect on 1 October.[194]

- 3 June: Governor John Lynch from New Hampshire signs a bill legalizing same-sex marriage .[195] The law took effect on 1 January 2010.

- 29 June: Governor Jim Doyle from Wisconsin signs into law a bill legalizing registered partnerships.[196] The law came into effect on 3 August.

- 28 October: The Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, also known as the Matthew Shepard Act, is passed by Congress,[197] and signed into law by President Barack Obama on October 28, 2009,[198] as a rider to the National Defense Authorization Act for 2010 (H.R. 2647). The measure expands the 1969 United States federal hate-crime law to include crimes motivated by a victim's actual or perceived gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability.[199]

- 18 December: District of Columbia Mayor Adrian Fenty signs a same-sex marriage bill into law.[200] It came into effect on 3 March 2010.[201]

2010s

[edit]2010

[edit]- Phyllis Frye became the first openly transgender judge appointed in the United States.[202][203][204]

- 4 August: U.S. District Judge Vaughn R. Walker rules in Perry v. Schwarzenegger that California's Proposition 8 is an unconstitutional violation of the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process and Equal Protection clauses.[205]

2011

[edit]- Civil unions are legalized in Illinois (31 January),[206] Hawaii (23 February),[207] Delaware (11 May)[208] and Rhode Island (1 July).[209]

- 24 June: Governor Andrew Cuomo from New York signs the state's Marriage Equality Act into law. It came into effect on 24 July.[210]

- 1 August: Washington state's Native American Suquamish tribe approves granting same-sex marriages.[211]

- 20 September: The "Don't ask, don't tell" policy stops being enforced. It was the official United States policy on military service by gays, bisexuals, and lesbians, instituted by the Clinton Administration on February 28, 1994, when Department of Defense Directive 1304.26 took effect.[122] The policy prohibited military personnel from discriminating against or harassing closeted gay or bisexual service members or applicants, while barring openly gay, lesbian, or bisexual persons from military service.

2012

[edit]

- 13 February: Governor Christine Gregoire from Washington signs a same-sex marriage bill into law.[212] However, opponents organized a referendum that took place on 6 November.

- 1 March: Governor Martin O'Malley from Maryland signs a same-sex marriage bill into law.[213][214][215] However, opponents organized a referendum that took place on 6 November.

- 9 May: President Barack Obama becomes the first sitting U.S. president to declare his support for legalizing same-sex marriage.[216]

- 6 June: Judge Barbara Jones of the District Court for the Southern District of New York finds section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act unconstitutional in Windsor v. United States.[217] The decision was appealed.

- 7 July: Representative Barney Frank of Massachusetts becomes the first member of Congress to enter into a same-sex marriage.[218]

- 5 September: The Democratic National Convention adopts a political platform that supports marriage equality for the first time in its history and opposes all constitutional amendments against same-sex marriage.[219]

- 6 November: Voters in Maine, Maryland, and Washington legalize same-sex marriage laws in referendums, becoming the first jurisdictions in the world to legalize same-sex marriage by popular vote,[220][221] while voters in Minnesota become the first to reject a constitutional amendment seeking to ban same-sex marriage in their state.[222]

- Kyrsten Sinema became the first openly bisexual person to be elected to Congress.[223]

- Tammy Baldwin was elected as the first openly gay senator in history.[224]

2013

[edit]- Same-sex marriage laws are approved by the State Legislatures of Rhode Island (2 May), Delaware (7 May), Minnesota (14 May), Hawaii (13 November) and Illinois (20 November).[225][226][227][228][229] Additionally, Colorado approves a civil unions law, on 21 March.[230]

- 26 June: The Supreme Court issues a ruling in Hollingsworth v. Perry that declares that supporters of Proposition 8, the same-sex marriage ban in California, lacked standing to appeal a court's 2010 decision that deemed the ban unconstitutional, thus legalizing same-sex marriage in California. Marriages resumed in the state two days later.[231]

- 26 June: The Supreme Court issues a ruling in United States v. Windsor570 U.S. 744 (2013) (Docket No. 12-307) that declares that restricting U.S. federal interpretation of "marriage" and "spouse" to apply only to opposite-sex unions, by Section 3 of the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), is unconstitutional under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment.[232][233][234][235] In the majority opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote: "The federal statute is invalid, for no legitimate purpose overcomes the purpose and effect to disparage and to injure those whom the State, by its marriage laws, sought to protect in personhood and dignity."[236]

- 21 August – 4 September: Same-sex marriages begin in several New Mexico counties after a series of judicial and county clerk decisions.[237][238][239][240][241][242]

- 27 September: The Supreme Court of New Jersey issues a ruling in Garden State Equality v. Dow that legalizes same-sex marriage in the state. Marriages started on 21 October.[243]

- DSM-5 was published by the American Psychiatric Association. Among other things, it eliminated the term "gender identity disorder," which was considered stigmatizing, instead referring to "gender dysphoria," which focuses attention only on those who feel distressed by their gender identity.[244]

2014

[edit]- February - September: As a direct result of United States v. Windsor, during the first ten months of 2014, courts around the country strike down same-sex marriage bans in Texas, Michigan, Arkansas, Idaho, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Utah, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Colorado, Virginia, Florida, Indiana and Wisconsin. Most rulings are stayed pending appeal, but the ones in Oregon and Pennsylvania come into effect.

- 6 October: The United States Supreme Court allows appeals court decisions striking down same-sex marriage bans in Virginia, Indiana, Wisconsin, Oklahoma, and Utah to stand, allowing same-sex couples to begin marrying immediately in those five states and creating binding legal precedent that has nullified bans in six other states in the Fourth, Seventh, and Tenth Circuits (Colorado, Kansas, North Carolina, South Carolina, West Virginia, and Wyoming).[245]

- October - November: New court rulings strike down same-sex marriage bans in Nevada, West Virginia, North Carolina, Alaska, Arizona, Wyoming, Kansas, Missouri, South Carolina, Montana and Mississippi.

2015

[edit]

- 26 June: The Supreme Court of the United States issues a landmark civil rights ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges (576 U.S. ___ (2015) (/ˈoʊbərɡəfɛl/ OH-bər-gə-fel) in which it declares that the fundamental right to marry is guaranteed to same-sex couples by both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The ruling legalizes same-sex marriage in all fifty states on the same terms and conditions as the marriages of opposite-sex couples, with all the accompanying rights and responsibilities.[246][247]

- Kate Brown became the first openly LGBT American governor after the resignation of John Kitzhaber. She was later reelected in 2016, becoming the first elected openly bisexual governor in US history.[248]

- Philadelphia became the first county government in the U.S. to raise the transgender pride flag in 2015. It was raised at City Hall in honor of Philadelphia's 14th Annual Trans Health Conference, and remained next to the US and City of Philadelphia flags for the entirety of the conference. Then-Mayor Michael Nutter gave a speech in honor of the trans community's acceptance in Philadelphia.[249]

2016

[edit]- 12 June: Omar Mateen, a 29-year-old security guard, killed 49 people and wounded 53 others in a terrorist attack inside Pulse, a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, United States. Orlando Police Department (OPD) officers shot and killed him after a three-hour standoff. This, known as the Orlando nightclub shooting, is the deadliest incident of violence against LGBT people in U.S. history, and the deadliest terrorist attack in the U.S. since the September 11 attacks in 2001. At the time, it was the deadliest mass shooting by a single shooter in the U.S., being surpassed the following year by the Las Vegas shooting. Pulse was hosting a "Latin Night" and thus most of the victims were Latinos. In 2018, evidence suggested that Mateen may not have known that Pulse was a gay nightclub, having even asked the security guard at the nightclub where all the women were.[250]

- For the first time the Justice Department used the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act to bring criminal charges against a person for selecting a victim because of their gender identity.[251][252] In that case Joshua Brandon Vallum pled guilty to murdering Mercedes Williamson in 2015 because she was transgender, in violation of the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act.[251][252]

2017

[edit]- February 26 – Moonlight, directed by Barry Jenkins, becomes the first LGBT film to win the Academy Award for Best Picture.[253]

2018

[edit]- 1 January – Openly transgender individuals were allowed to join the United States military starting at this time.[254]

- 2 January – Phillipe Cunningham was sworn in to represent the 4th ward in the Minneapolis City Council. He was the first openly trans African American man elected to public office in the United States.[255]

- 2 January – Andrea Jenkins was sworn in to represent the vice-presidency and the 8th ward in the Minneapolis City Council. She was the first openly trans African American woman elected to public office in the United States.[256]

- Danica Roem became the first openly transgender person to be elected to, and the first to serve in, any U.S. state legislature.[note 4][258][259]

- Sharice Davids is elected as one of the first two Native American women in Congress and the first lesbian congresswoman from Kansas.[260]

- America's first citywide Bi Pride event was held, in West Hollywood.[261]

- Patricio Manuel became the first openly transgender male to box professionally in the United States, and, as he won the fight, the first openly transgender male to win a pro boxing fight in the U.S.[262]

2019

[edit]- 8 January – Jared Polis began to serve as governor of Colorado, the first openly gay person elected as an American governor.[263]

- Pete Buttigieg became the first openly gay presidential candidate from a major party.[264]

2020s

[edit]2020

[edit]- 6 February — Virginia became the first state in the American South to offer legal protections in employment, housing and public accommodations to LGBT citizens.[265]

- March—April — Four unsolved murders of transgender people occurred in Puerto Rico in two months.[266]

- June 14 — An estimated 15,000 people marched in Brooklyn, New York in opposition to violence against Black trans people. This was one of many Pride 2020 demonstrations that overlapped with the George Floyd protests.[267]

- June 15 — In the case Bostock v. Clayton County, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibited employment discrimination against LGBTQ people, on the grounds that any such discrimination must necessarily be based on the sex of the victim, which is expressly prohibited by the statute.[268]

2021

[edit]- 2 February — Pete Buttigieg became the first openly gay non-acting member of the Cabinet of the United States,[269] and the first openly gay person confirmed by the Senate to a Cabinet position.[270]

See also

[edit]- Timeline of LGBTQ history

- Timeline of LGBTQ history in New York City

- Timeline of LGBT Mormon history

- History of gay men in the United States

- History of lesbianism in the United States

- History of transgender people in the United States

Notes

[edit]- ^ A smaller-scale riot broke out in 1959 in Los Angeles, when the drag queens, lesbians, gay men, and transgender people who hung out at Cooper Do-nuts and who were frequently harassed by the LAPD fought back after police arrested three people, including John Rechy. Patrons began pelting the police with donuts and coffee cups. The LAPD called for back-up and arrested a number of rioters. Rechy and the other two original detainees were able to escape. Faderman, Lillian and Stuart Timmons (2006). Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians. Basic Books. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-465-02288-X

- ^ At the time, the term "gay" was commonly used to refer to all LGBT people.

- ^ Note: – as Brandon Teena was never his legal name, it is uncertain the extent to which this name was used prior to his death. It is the name most commonly used by the press and other media. Other names may include his legal name, as well as "Billy Brenson" and "Teena Ray"

- ^ Althea Garrison served a term in the Massachusetts House of Representatives after being outed subsequent to winning her election in 1992.[257] Stacie Laughton was elected in 2012 to the New Hampshire House of Representatives while openly transgender, but did not serve her term.[258]

References

[edit]- ^ Rosenberg, Eli (June 24, 2016). "Stonewall Inn Named National Monument, a First for the Gay Rights Movement". The New York Times. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ "Workforce Diversity The Stonewall Inn, National Historic Landmark National Register Number: 99000562". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ Hayasaki, Erika (May 18, 2007). "A new generation in the West Village". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved July 3, 2017.

- ^ "Walt Whitman, an American". National Review. August 31, 2019. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ Stabbe, Oliver (2016-03-30). "Queens and queers: The rise of drag ball culture in the 1920s". National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2022-10-27.

- ^ Fleeson, Lucinda (June 27, 2007). "The Gay '30s". Chicago Magazine. Retrieved 2022-10-27.

- ^ Whitcomb, Selden L. and Matthews, Brander, Chronological Outlines of American Literature, Norwood Press, 1893, p. 186

- ^ Austen, Roger, Playing the Game: The Homosexual Novel in America, Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1977, p. 9

- ^ "2019 Creative Nonfiction Grantee: Channing Gerard Joseph". whiting.org. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ Alma J. Hill (March 1, 2018). "An Homage to Five Generations of Black Entertainers in Orlando". watermark. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Gay Histories and Cultures, p482

- ^ Chauncey, George (Aug 1, 2008). Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-7867-2335-5.

- ^ Gifford, James J. "Stevenson, Edward Irenaeus Prime- (1868-1942)". glbtq.com. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Robertson, Patrick (1993). The Guinness Book of Movie Facts & Feats (5th ed.). Abbeville Press. p. 63. ISBN 1558596976.

- ^ "Timeline: Milestones in the American Gay Rights Movement". PBS. WGBH Educational Foundation. Retrieved 12 April 2013.

- ^ Gattuso, Reina (September 3, 2019). "The Founder of America's Earliest Lesbian Bar Was Deported for Obscenity". Atlas Obscura.

- ^ Burger, John R. One-Handed Histories: The Eroto-Politics of Gay Male Video Pornography. New York: Harrington Park Press, 1995. ISBN 1-56023-852-6

- ^ Benshoff, Harry M.; Griffin, Sean (2005). Queer images: A History of Gay and Lesbian Film in America. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7425-1972-5.

- ^ Gilbert, Nora (January 9, 2013). Better Left Unsaid. Stanford University Press. doi:10.11126/stanford/9780804784207.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-8047-8420-7.

- ^ a b Lo, Malinda. Back in the Day: The Ladder, America's First National Lesbian Magazine, afterellen.com; retrieved March 10, 2008.

- ^ Baumgardner, Jennifer (2008) [2008]. Look Both Ways: Bisexual Politics. New York, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Reprint edition. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-374-53108-9.

- ^ Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, p. 656

- ^ Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, p. 651

- ^ Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement. Marc Stein. Taylor & Francis. 2012. ISBN 978-1-280-77657-1. OCLC 796932345.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "McCarthyism, Homophobia, and Homosexuality: 1940s-1950s". OutHistory. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Baram, Marcus (April 14, 2017). "Eavesdropping on Roy Cohn and Donald Trump". The New Yorker. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ^ "Roy Cohn, Aide to McCarthy and Fiery Lawyer, Dies at 59". partners.nytimes.com. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- ^ Nicholas von Hoffman (March 1988). "Life Magazine – The Snarling Death of Roy M. Cohn". maryellenmark.com.

- ^ Johnson, David K. (2004). The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government. University of Chicago Press. 22. ISBN 0-226-40190-1.

- ^ Rodger McDaniel, Dying for Joe McCarthy's Sins: The Suicide of Wyoming Senator Lester Hunt (WordsWorth, 2013), ISBN 978-0983027591

- ^ White, William S. (May 20, 1950). "Inquiry by Senate on Perverts Asked" (PDF). The New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "LGBT Rights Milestones Fast Facts". CNN. 2015-06-21. Archived from the original on 2015-06-22. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ^ "21 Transgender People Who Influenced American Culture". Time Magazine.

- ^ Castle, Terry (May 23, 2006). "Pulp Valentine". Slate. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ^ Smith, Nathan (November 20, 2015). "Gay Syllabus: The Talented Patricia Highsmith". Out Magazine. Retrieved 14 October 2019.

- ^ Howard, Josh (April 27, 2012). "April 27, 1953: For LGBT Americans, a Day That Lives in Infamy". Huffpost. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Valelly, Rick (October 1, 2018). "How Gay Rights Activists Remade the Federal Government". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Perdue, Katherine Anne (June 2014). Writing Desire: The Love Letters of Frieda Fraser and Edith Williams—Correspondence and Lesbian Subjectivity in Early Twentieth Century Canada (PDF) (PhD). Toronto, Canada: York University. p. 276. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- ^ Faderman, Lillian and Stuart Timmons (2006). Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians. Basic Books. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-465-02288-X

- ^ Miller, Neil (1995). Out of the Past: Gay and Lesbian History from 1869 to the Present. pg. 347. New York, Vintage Books. ISBN 0-09-957691-0.

- ^ Shilts, Randy (1982). The Mayor of Castro Street. pgs. 56-57. New York, St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-52331-9.

- ^ Kohler, Will (July 28, 2019). "Gay History – July 28, 1961: Illinois Becomes First State to Rescind Sodomy Law Possibly By Mistake". Back2Stonewall. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ Alwood, Edward (1998). Straight News. P.41. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-08437-4.

- ^ Byron, Stuart (August 9, 1967). "Homo Theme 'Breakthrough'". Variety. p. 7.

- ^ "Philadelphia Freedom: The Dewey's Lunch Counter Sit-In". Queerty. October 10, 2011. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ "Compton's Cafeteria and Dewey's Protest". Transgender Center. Transgender Foundation of America. December 19, 2009. Retrieved May 15, 2012.

- ^ Boyd, Nan Alamilla (2004). "San Francisco" in the Encyclopedia of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgendered History in America, Ed. Marc Stein. Vol. 3. Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 71–78.

- ^ "Press Release regarding the 1966 raid on the Black Cat bar". The Tangent Group. Archived from the original on 2015-04-27. Retrieved 2013-12-04.

- ^ Branson-Potts, Hailey (2017-02-08). "Before Stonewall, there was the Black Cat; LGBTQ leaders to mark 50th anniversary of protests at Silver Lake tavern". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2022-10-26.

- ^ Tobin, Kay & Wicker, Randy (1972). The Gay Crusaders. New York: Paperback Library. p. 80. OCLC 1922404.

- ^ Craig Rodwell Papers, 1940–1993, New York Public Library (1999). Retrieved on August 24, 2017.

- ^ a b Marotta, Toby, The Politics of Homosexuality, pg. 65 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1981) ISBN 0-395-31338-4

- ^ Howard Smith's Scenes column, Village Voice, March 21, 1968, Vol. XIII, No. 23 (March 21, 1968 – republished April 19, 2010) Archived June 30, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Craig Rodwell Papers, 1940-1993, New York Public Library (1999). Retrieved on July 25, 2011.

- ^ Stein, Marc (13 April 2021). ""WHERE PERVERSION IS TAUGHT": THE UNTOLD HISTORY OF A GAY RIGHTS DEMONSTRATION AT BUCKS COUNTY COMMUNITY COLLEGE, MAY 9, 1968". OutHistory. Retrieved 31 January 2023.

- ^ "Brief History of the Gay and Lesbian Rights Movement in the U.S." University of Kentucky. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ Nell Frizzell (June 28, 2013). "Feature: How the Stonewall riots started the LGBT rights movement". Pink News UK. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ "Stonewall riots". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 19, 2017.

- ^ U.S. National Park Service (October 17, 2016). "Civil Rights at Stonewall National Monument". Department of the Interior. Retrieved August 6, 2017.

- ^ "Obama inaugural speech references Stonewall gay-rights riots". Archived from the original on 2013-05-30. Retrieved 2013-01-21.

- ^ Gould, Robert E. (24 February 1974). What We Don't Know About Homosexuality. ISBN 9780231084376. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e f Alwood, Edward (1996). Straight News: Gays, Lesbians, and the News Media. Columbia University. p. 94. ISBN 0-231-08436-6. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

purple hand gay -john gay.

- ^ Bell, Arthur (28 March 1974). Has The Gay Movement Gone Establishment?. Village Voice. ISBN 9780231084376. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ a b c Van Buskirk, Jim (2004). "Gay Media Comes of Age". Bay Area Reporter. Archived from the original on 2015-07-05. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ Friday of the Purple Hand. The San Francisco Free Press. November 15–30, 1969. ISBN 9780811811873. Retrieved 2008-01-01. courtesy the Gay Lesbian Historical Society.

- ^ a b ""Gay Power" Politics". GLBTQ, Inc. 30 March 2006. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ Montanarelli, Lisa; Ann Harrison (2005). Strange But True San Francisco: Tales of the City by the Bay. Globe Pequot. ISBN 0-7627-3681-X. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ Newspaper Series Surprises Activists. The Advocate. 24 April 1974. ISBN 9780231084376. Retrieved 2008-01-01.

- ^ Sources: Michael McConnell Files, "America’s First Gay Marriage" (binder #7), Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries.

- University president Eric Kaler apologized to McConnell for the treatment inflicted by the Board of Regents in 1970.

- 22 June 2012: Anon., "News", University News Service. "U of M President Eric Kaler has called McConnell's treatment reprehensible, regrets that it occurred and says that the university's actions at that time were not consistent with the practices enforced today at the university."

- 17 February 2020: McConnell received a letter from Robert Burgett (Senior Vice President, University of Minnesota Foundation) announcing his enrollment as a member of the Heritage Society of the President's Club.

- University president Eric Kaler apologized to McConnell for the treatment inflicted by the Board of Regents in 1970.

- ^ Sources: Michael McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary" (volumes 5a-e), Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries.

- March 1967: On Baker's 25th Birthday, McConnell insisted that he would accept Baker's invitation to be lovers if, and only if, he could find a way for the relationship to be recognized as a "legal" marriage.

- June 1970: University Librarian mailed an offer of employment to McConnell.

- July 1970: James F. Hogg (Secretary, the Board of Regents) arranged for a letter to be delivered to McConnell:

- The Board accepted the recommendation of its Executive Committee "That the appointment of Mr. J. M. McConnell to the position of the Head of the Cataloging Division of the St. Paul Campus Library at the rank of Instructor not be approved on the grounds that his personal conduct, as represented in the public and University news media, is not consistent with the best interest of the University."

- 1971: A federal court of appeals allowed such discrimination to continue.

- 1972: Hennepin County Library, then a diverse and growing system of 26 facilities, hired McConnell.

- ^ Sources: Michael McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary", (volumes 6a-b), Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries.

- As a student body president (elected 1971, re-elected 1972), he was known by different names:

- March 1942: Richard John Baker, Certificate of Birth

- September 1969: Jack Baker, name adopted to lead activists demanding gay equality

- August 1971: Pat Lyn McConnell, married name via Decree of Adoption

- As a student body president (elected 1971, re-elected 1972), he was known by different names:

- ^ May: in Minneapolis, within the Fourth Judicial District, which includes all of Hennepin County.

- ^ Sources: Michael McConnell Files, "Full Equality, a diary", (volume 2ab), Tretter Collection in GLBT Studies, U of M Libraries.

- May 1970: Letter addressed to Gerald R. Nelson from George M. Scot, County Attorney

- page 6: "The consequences of an interpretation of our marriage statutes which would permit males to enter into the marriage contract could be to result in an undermining and destruction of the entire legal concept of our family structure in all areas of law."

- May 1970: Letter addressed to Gerald R. Nelson from George M. Scot, County Attorney

- ^ Coen, Sasha (2015-03-17). "How One Movie Changed LGBT History". Time. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ^ Martin, Douglas (September 14, 2011). "Arthur Evans, Leader in Gay Rights Fight, Dies at 68". New York Times. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Franke-Ruta, Garance (March 26, 2013). "The Prehistory of Gay Marriage: Watch a 1971 Protest at NYC's Marriage License Bureau". The Atlantic. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ Denniston, Lyle (July 4, 2012). "Gay marriage and Baker v. Nelson". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved October 18, 2012.

- ^ Denniston, Lyle (July 4, 2012). "Gay marriage and Baker v. Nelson". SCOTUSblog. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- ^ "MGA HTML Statutes". Mlis.state.md.us. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "Upstairs Lounge Fire Memorial, 40 Years Later". Nola Defender. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017. Retrieved September 21, 2014.

- ^ Delery-Edwards, Clayton (June 5, 2014). The Up Stairs Lounge Arson: Thirty-two Deaths in a New Orleans Gay Bar, June 24, 1973 (First ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-0786479535.

- ^ Freund, Helen (June 22, 2013). "UpStairs Lounge fire provokes powerful memories 40 years later". New Orleans Times-Picayune. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ^ Townsend, Johnny (2011). Let the Faggots Burn: The UpStairs Lounge Fire. BookLocker.com, Inc. ISBN 9781614344537.

- ^ a b "Revisiting a Deadly Arson Attack on a New Orleans Gay Bar on Its 42nd Anniversary". VICE. 1973-06-24. Retrieved 2018-06-27.

- ^ Cantor, Donald J.; et al. (2006). Same-Sex Marriage: The Legal and Psychological Evolution in America. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. pp. 117–8. ISBN 9780819568120.; Kentucky Court of Appeals: Jones v. Hallahan, November 9, 1973

- ^ Bayer, Ronald (1987). Homosexuality and American Psychiatry: The Politics of Diagnosis. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02837-0.[page needed]

- ^ "Meet the lesbian who made political history years before Harvey Milk". NBC News. April 2, 2020. Retrieved April 3, 2022.

- ^ Sanders, Eli (20 October 2005). "Marriage Denied". The Stranger.

- ^ "Will Roscoe papers and Gay American Indians records". Online Archive of California (OAC). University of California Libraries.

- ^ Fitzsimons, Tim (June 3, 2019). "#Pride50: Elaine Noble — America's first out lawmaker". NBC News. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ Lichtenstein, Grace (April 27, 1975). "Homosexual Weddings Stir Controversy in Colorado" (PDF). New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2012.

- ^ Harris, Kyle (August 13, 2014). "Clela Rorex Planted the Flag for Same-Sex Marriage in Boulder Forty Years Ago". Westword Newsletters. Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

- ^ Leagle, Inc.: Adams v. Howerton, 486 F. Supp. 1119 (C.D.Cal.1980) Archived March 21, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed July 30, 2011

- ^ a b Diane Kaufman & Scott Kaufman, Historical Dictionary of the Carter Era (Scarecrow Press, 2013), p. 180.

- ^ Baim, Tracy (January 24, 2013). "Author Julia Penelope dead at 71". Windy City Times. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ Debra L. Merskin (12 November 2019). The SAGE International Encyclopedia of Mass Media and Society. SAGE Publications. pp. 2086–. ISBN 978-1-4833-7554-0.

- ^ Seabaugh, Cathy (February 1994). "BLK: Focused Coverage for African-American Gays & Lesbians". Chicago Outlines.

- ^ Chestnut, Mark (June 1992). "BLK: Getting Glossy". Island Lifestyle.

- ^ "The Living Room". Matt & Andrej Koymasky. June 28, 2002. Retrieved February 10, 2008.

- ^ "Independent Lens: SISTERS OF '77". PBS. Archived from the original on 7 March 2007. Retrieved 2013-05-13.

- ^ glbtq >> social sciences >> Transgender Activism Archived 25 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Jennifer P (June 18, 2015). "First in the Nation - Wisconsin's Gay Rights Law". Milwaukee Public Library. Retrieved May 6, 2020.

- ^ Freedom to Marry (2013-03-12). "Marc Solomon honored with Congressman Gerry E. Studds Visibility Award". Freedom to Marry. Retrieved 2018-06-27.

- ^ Scherr, Judith (2013-06-28). "Berkeley, activists set milestone for domestic partnerships in 1984". East Bay Times. Archived from the original on 2022-04-09. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ Lindsey, Robert (1985-03-18). "The talk of West Hollywood; West Hollywood acting on pledges". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2015-05-24. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ Lang, Nico (2020-03-07). "Meet The People Who Made History as The World's First Official Same-Sex Partners". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on 2022-04-09. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986).

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

- ^ Hoffman, Jordan (2015-04-13). "Barney Frank Talks Hillary Clinton, Gay Marriage, & His New Book". Biography. Retrieved 2018-06-27.

- ^ Bishop, Katherine (1989-05-31). "San Francisco Grants Recognition To Couples Who Aren't Married". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2018-08-19. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ "San Francisco Set to Define 'Family'". Christianity Today. 1989-10-20. Archived from the original on 2020-10-20. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ "1989 local elections and the defeat of Propositions S and P - 10 November 1989". BBC. 1989-11-10. Archived from the original on 2021-12-02. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ a b Reinhold, Robert (1990-10-29). "Campaign Trail; 2 Candidates Who Beat Death Itself". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2012-11-08. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ Russell, Ron (December 8, 1988). "Removal of 'Gay Pride' Flag Ordered: Tenant Suit Accuses Apartment Owner of Bias". Los Angeles Times. Part 9, 6.

- ^ Hansen, Mark (March 1, 1992). "Gay-Rights Victory". ABA Journal. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ N.R. Gallo, Introduction to Family Law (Thomson Delmar Learning, 2004), 145, available online, accessed October 7, 2012

- ^ Blair, Chad (2021-05-24). "How Hawaii Helped Lead The Fight For Marriage Equality". Honolulu Civil Beat. Archived from the original on 2021-05-24. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ "U.S. 8th Circuit Court of Appeals – JoAnn Brandon v Charles B. Laux". FindLaw. Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- ^ Howey, Noelle (March 22, 2000). "Boys Do Cry". Mother Jones. Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- ^ Jeon, Daniel. "Challenging Gender Boundaries: A Trans Biography Project, Brandon Teena". OutHistory.org. Retrieved 4 December 2015.

- ^ a b "Hate crimes legislation updates and information: Background information on the Local Law Enforcement Hate Crimes Prevention Act (LLEHCPA)" Archived March 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. National Youth Advocacy Coalition. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ a b "25 Transgender People Who Influenced American Culture". Time. Retrieved 2016-12-13.

- ^ a b "Department of Defense Directive 1304.26". Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ^ "Veto on Domestic Partners". The New York Times. 1994-09-12. Archived from the original on 2022-04-10. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ Garside, Emily (2019-01-25). ""Bisexuals, Trisexuals, Homo Sapiens"". Slate. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 2022-04-17.

- ^ a b c Romer v. Evans, 517 U.S. 620 (1996).

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

- ^ Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 U.S. 186 (1986).

- ^ Linder, Doug. "Gay Rights and the Constitution". University of Missouri-Kansas City. Retrieved August 27, 2011.

- ^ Wald, Kenneth & Calhoun-Brown, Allison (2014). Religion and Politics in the United States. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 347. ISBN 9781442225558 – via Google Books..

- ^ Hames, Joanne & Ekern, Yvonne (2012). Constitutional Law: Principles and Practice. Cengage Learning. p. 215. ISBN 978-1111648541 – via Google Books.

- ^ Smith, Miriam (2008). Political Institutions and Lesbian and Gay Rights in the United States and Canada. Routledge. p. 88. ISBN 9781135859206 – via Google Books.

- ^ Schultz, David (2009). Encyclopedia of the United States Constitution. Infobase Publishing. p. 629. ISBN 9781438126777 – via Google Books.

- ^ Bolick, Clint (2007). David's Hammer: The Case for an Activist Judiciary. Cato Institute. p. 80 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ MetroWeekly: Chris Geidner, "Becoming Law," 29 September 2011, accessed 3 March 2012

- ^ Oshiro, Sandra (1996-12-06). "Hawaiian judge puts same-sex marriage ruling on hold". The Nation. Thailand: Reuter. p. A12. Retrieved 2010-08-18.

- ^ Essoyan, Susan (1997-04-30). "Hawaii Approves Benefits Package for Gay Couples". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2021-03-29. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ Cogan, Marin (2007-12-20). "First Ladies". The New Republic. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ^ "Tammy Baldwin: Openly gay lawmaker could make history in Wisconsin U.S. Senate race - Chicago Tribune". Articles.chicagotribune.com. 2012-10-19. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- ^ "About Us - Matthew Shepard Foundation". Matthew Shepard Foundation. Retrieved 2017-11-19.

- ^ 'Remembering Rita Hester' November 15, 2008, Edge Boston

- ^ Nancy Nangeroni (1999-02-01). "Rita Hester's Murder and the Language of Respect". Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ Irene Monroe (2010-11-19). "Remembering Trans Heroine Rita Hester". Huffington Post. Retrieved 9 November 2013.

- ^ Clarkson, Kevin; Coolidge, David; Duncan, William (1999). "The Alaska Marriage Amendment: The People's Choice On The Last Frontier". Alaska Law Review. 16 (2). Duke University School of Law: 213–268. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- ^ Brian van de Mark (10 May 2007). "Gay and Lesbian Times". Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Fairyington, Stephanie (12 November 2014). "The Smithsonian's Queer Collection". The Advocate. Retrieved 5 June 2015.

- ^ Smith, G. "Biography". Gwensmith.com. Archived from the original on April 24, 2008. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ Jacobs, Ethan (November 15, 2008). "Remembering Rita Hester". EDGE Boston.

- ^ "Transgender Day of Remembrance". Human Rights Campaign. Archived from the original on November 15, 2019. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ "Trans Day of Remembrance". Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition. 2013. Archived from the original on August 14, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ^ Millen, Lainey (November 20, 2008). "North Carolinians mark Transgender Remembrance Day". QNotes.

- ^ AB 26. Legislative Counsel of California. 1999–2000 Session.

- ^ Goldberg, Carey (December 21, 1999). "Vermont High Court Backs Rights of Same-Sex Couples". New York Times. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "National News Briefs; Governor of Vermont Signs Gay-Union Law". The New York Times. 2000-04-27. Archived from the original on 2013-12-20. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

- ^ "House Committee activity". Religioustolerance.org. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Goldberg, Carey (April 26, 2000). "Vermont Gives Final Approval to Same-Sex Unions". New York Times. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ "Transgender Flag Flies In San Francisco's Castro District After Outrage From Activists" by Aaron Sankin, HuffingtonPost, 20 November 2012.

- ^ Gerstenfeld, Phyllis B. (2004). Hate crimes: causes, controls, and controversies. SAGE. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-7619-2814-0. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ Marshall, Carolyn (13 September 2005). "Two Guilty of Murder in Death of a Transgender Teenager". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 August 2017 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Sam Wollaston (27 May 2005). "Body politics". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ a b Szymanski, Zak (15 September 2005). "Two murder convictions in Araujo case". Bay Area Reporter. Archived from the original on 2009-02-01. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- ^ Shelley, Christopher A. (2008-08-02). Transpeople: repudiation, trauma, healing. University of Toronto Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8020-9539-8. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- ^ Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U.S. 558 (2003).

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

This article incorporates public domain material from this U.S government document.

- ^ Belluck, Pam (19 November 2003). "Marriage by Gays Gains Big Victory in Massachusetts". New York Times. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- ^ Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 22, sec. 2710

- ^ Burge, Kathleen (18 November 2003). "SJC: Gay marriage legal in Mass". The Boston Globe.

- ^ Roberts, Joel (November 2, 2004). "11 States Ban Same-Sex Marriage". CBS News. Associated Press. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ "Judge Voids Same-Sex Marriage Ban in Nebraska". New York Times. May 13, 2005. Retrieved November 25, 2012.